What Driving A Hillclimb Does To Your Brain

You've all seen the videos. Cars screaming up hills, some with wings larger than snow plows. Pikes Peak comes to mind. These are hillclimb races, where the only thing you compete against is the clock. I got to try it out. It did weird things to how my brain perceived time.

(Full disclosure: Subaru flew us out to England to attend the 2019 Goodwood Revival. While on the way, we stopped at the Shelsley Walsh hillclimb to try out a few runs up the hill.)

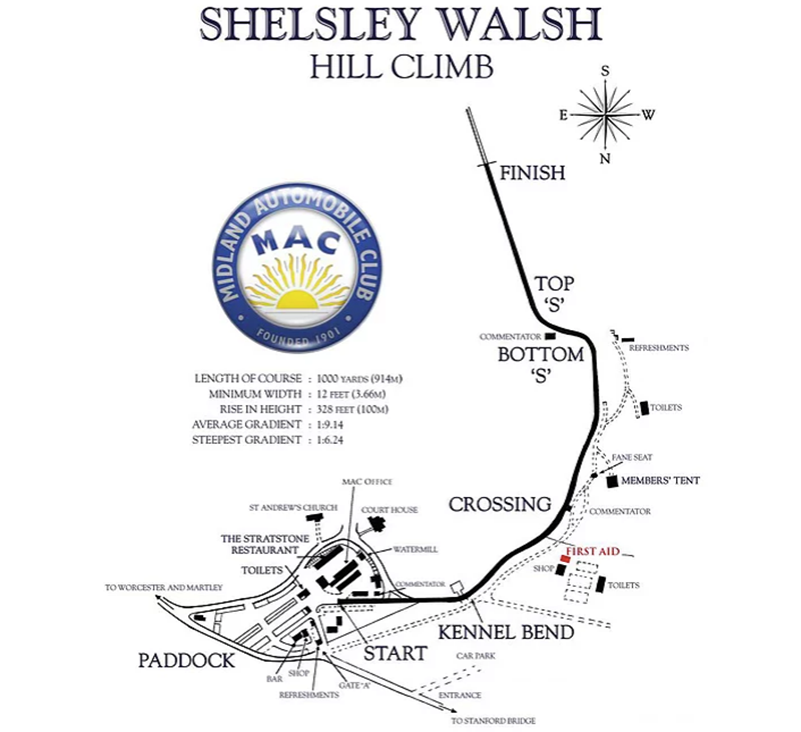

Located in central, picturesque England, Shelsley Walsh is the oldest motorsport venue in the world that still uses its original course, according to its website. First opened in the very early 1900s, the entire course is 914 meters long (about half a mile), rises 328 feet and is 12 feet wide in its narrowest section.

Twelve feet sounds pretty wide, but when you are hurtling through at speed in a car, it's a different story. There are also no runoffs. I saw this for myself during a morning stroll up the course before anyone was allowed behind the wheel.

"Anytime you get it wrong, there will be no way to go," Mark Goodyear, a Shelsley Walsh instructor and historic Formula Two racer, told a group of journalists and myself during our safety briefing.

Having only ever driven on circuits up until this point, there were a few things I needed to get used to. A new mindset, really.

See, a hillclimb is a timed run. "You cannot afford a mistake at any time of any type whatsoever. As soon as you've lost your time on one mistake, you can't make it up," Goodyear elaborated in an interview. "Everything has to be precise. You're against the clock, that's one of the key bits. If you miss a gear, that's half a second you're going to lose. If you put the brakes on early, that's another half a second."

On a circuit, if you flub a corner, you can theoretically do it over again one lap later. Maybe you can exit more quickly on the following corner. You can easily make up for it. That sort of luxury doesn't exist on a hillclimb.

And, of course, there's the physics of driving on a hill itself. "Generally, you need to be on the brakes as you enter a corner," Goodyear went on. "Weight transfer goes all to the front and turns the car in. And then you're off the weight and back on the power. As soon as you hit the clipping point on the hillclimb, you should be back on the power."

"Here at Shelsley, for instance, you set your hillclimb car up to be able to go flat through the first corner. Good grip, good aero, good to the roll bars. Most hillclimbs start off in the first corner and you'll need the mechanical grip in and out."

This was very different from the advice I had been sticking with. Goodyear addressed that, too.

"On a circuit, in theory, as you do your clipping point, as you're unwinding your steering, you should be gently easing your accelerator on. In a hillclimb, you're on it the minute you've done your turn point. You're on it, straight away. There's no time to be had."

For our runs, Subaru provided a fleet of five WRX STIs and one Type RA. I took my first run slow, focusing on my line and familiarizing myself with the course. The Shelsley record is 22.58 seconds, set in a Gould GR55 NME hillclimb car. I was under no illusion that I'd come anywhere close to that, so I settled into merely learning how to do it.

Soon, the air was thick with the smell of clutch from people dumping them for a faster start off the line.

During my run, I sat at the starting point, waiting for the green light. One of the marshals stuck a rubber stopper behind my back left tire, so I could focus on just starting and not worrying about the brake. The light turned green and I was off, flinging the car around the first corner as fast as I dared to go.

Which wasn't very fast. At speed, the course narrows impossibly and terror from wrecking held me back from going all out. Up I went, through the trees and around the tight "S" at the top of the hill before straightening the car out and flooring it down the straight toward the finish. I think I might have done the entire thing in second gear, third at the end.

But as the day went on and I got more and more comfortable with the course, time started doing funny things. It seemed to run slower, sometimes stopping altogether in certain places. My foot was to the floor in parts of the course, driving the Subaru all the way up toward redline, but nothing else seemed to be moving outside of the car. No sights, no sounds, besides what was going on at that moment in that car. Just it and me, aiming to nail each corner perfectly, to wring every ounce of speed from each turn, to scrub time.

It felt like I was driving the course for at least five minutes, when in reality I was told our laps all took well under a minute. I suppose that's what tunnel vision does.

Up past the finish line (which looks out across an idyllic field of grazing brown cows), ambient sound kicked back on. The wind in the trees, the bleats of the farm animals and the friendly comments from the marshal about the weather all swelled back inside the cabin.

I put the Subaru in neutral and let it roll back down the hill, my foot hovering over the brake. Hillclimbs are a different kind of fun. Typically, on a course, I don't go this deaf when I'm concentrating. Time never stands this still. But there was something about being so focused on the clock on a hill that my mind and perception of time dramatically changed.

Intellectually, yes, you're racing other people. You're racing their times. But when you're out there on a hillclimb, nobody is there with you. You can't help but feel you're racing yourself.

Everything outside of that goes dark.