The World's Fastest Death Cult

At a certain point, you stop being shocked by how many people have died here. The shock is how many are still alive.

The spot is easy to get to, and anyone is allowed there. Start at the grandstands and walk down the hill. Go past the t-shirt tent and the ice cream vans and the stunt rider show. Keep going past the parking lot and the picnic field, hop the little stone wall and walk through the public garden. It's just past the bridge, the back side of a school. Perch yourself up against the fence and you'll be just a few feet from them.

The riders. They're doing 160, 170, 180 mph here, depending on the bike. It'll be 190 at the bottom of the hill, called Bray Hill, where there's a compression and the bike scrapes the ground before it hops up and wheelies.

You think of them as burly, out-of-the-past men. But seeing them on these bikes, even the biggest and the fastest ones, the impression isn't of bravery or daring.

It's fragility.

You only get a fraction of a second watching them coming, steaming down the hill on this two lane road. But you get a few seconds longer watching them going. They shoot past you in a flash, but there's a couple moments to take in how they bend right up to the street gutter, nearly graze the curb, then drop away into the horizon.

Here at the Isle of Man TT Race, the infamously deadly motorcycle race that's been running on public streets on this tiny island in the Irish Sea since 1907, the sound is hard to process. These races are the last of their kind — big feature races held on public roads.

In the earliest days of motorsports, nearly every major race was held on public roads. The last one of the first great era was the event that nearly banned motor racing altogether, the 1903 Paris-Madrid race. It was believed to be the deadliest up to its time. Eight dead, rumors of over a hundred injured. The reason for the huge number of wrecks was that the cars were faster than any of the turn of the century French or Spanish spectators could imagine. A number of drivers crashed avoiding people and children standing right in the middle of the road, not expecting a car to come down the road much faster than a horse and buggy.

And that's what the noise is like here at the TT. You hear the bikes coming for what seems like an eternity, and they still shoot past you before you turn to look. It's hard to whip your head fast enough to catch the riders go by. They pass you with such physical violence that it's like the exhaust's sound waves have collapsed into a solid.

Here, atop Bray Hill, the lasting impression is seeing the bike and the rider in a rear silhouette. The pair is widest in the middle, around the engine. It's narrow at the top, peaking at the rider's helmet, and narrower still at the bottom. You see just how thin the tire is, one small strip of a contact patch connecting this human to the ground. The whole shape looks like a flickering candle.

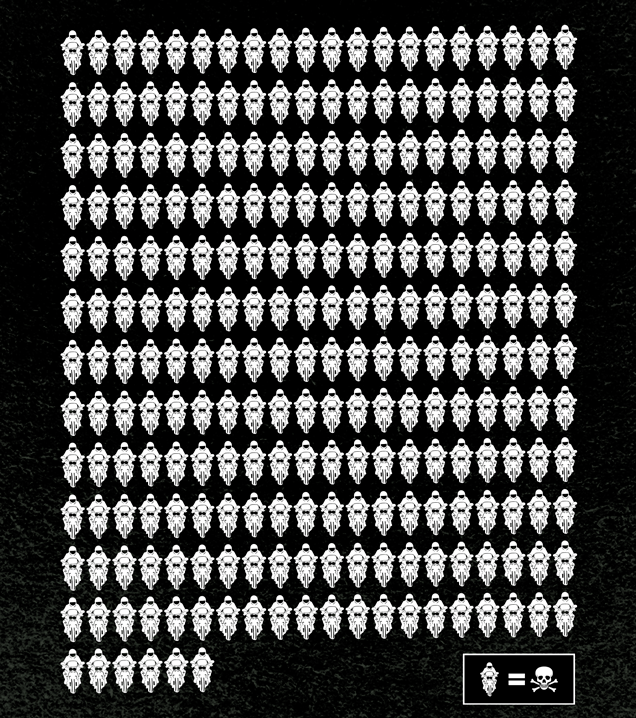

Everyone outside the TT races talks about the deaths. It's hard not to. More than 200 people have died on the Snaefell Mountain Course. The island shuts down its 37-mile ring road every morning and reopens it every evening for two weeks in the early summer for racing. The course starts in the main town and snakes past open fields, through moors, into woods, and up past the Isle's tallest mountain, Snaefell.

The sharpest corners and objects get some kind of protection — I saw hay bales on some of the more vicious looking embankments, and I saw a what looked like a mattress wrapped around a telephone box — but most of the course is just as it is for normal traffic.

The difference in the race is that these riders face the road's hundreds of corners flat out.

Experience is the only way to survive racing in the TT. There's a great video by the TT's current most popular rider, the shitpiss straight-talking truck mechanic Guy Martin, where he narrates the course. He describes corners by how many days or weeks of practice it takes to get them right. It was the fastest TT ever, this year, won by one of the oldest riders in the field. Here's the veteran rider himself, number one John McGuinness, on his 1000cc Honda.

Many of those who die aren't even racers. They're public amateurs trying their own on the public roads of the Isle. They're even let loose on the course one day in the middle of the two-week spectacle that is the TT.

They call that day Mad Sunday, and they make the infamous mountain section of the course one-way, just like in the races. If you're looking for the most hilariously tasteless merchandise to bring back from the IOM, get yourself something with Mad Sunday printed on it.

When I found myself at the TT races this year, shipped out by Subaru to tout their sponsorship of the event, the focus wasn't on death at all. I sort of expected that people would have a cavalier attitude about risk and fatality. The Isle of Man has long been an anti-Health And Safety place. I always knew it as the little independent island where (outside of the small seaside resort towns) there were no speed limits.

Indeed that's why there's racing at the Isle of Man at all. Back around the turn of the century, the UK held a strict 25 mph speed limit on all of its roads and explicitly banned any motor racing on public highways.

That's why the legendary circuits of other European countries like France and Italy are road courses, that's why England is the site of the first purpose-built motor racing circuit (Brooklands, near London), and that's why motorcycle enthusiasts started taking the ferry to the Isle of Man to hold their competitive events over a hundred years ago.

I thought this sort of free spirit in legal choice would extend to people's feelings about the riders. I thought they would be maybe a bit flippant about assuming personal risk, or knowing the dangers, or not having the nanny state hold anyone's hand.

But there's real sadness when there's a death at the TT. One rider died before I even arrived, during practice. A Frenchman. He crashed on a straight section of the course. Nobody is exactly sure why he lost it.

And another rider nearly lost his life while I was there, but was taken to a hospital and saved. Here's a picture of him, Jamie Hamilton. I took it a few hours before he was airlifted away from his crash. At 24, he's a year younger than I am.

Hamilton's crash red-flagged the top race at the Isle of Man, the Senior TT. It's the one with the fastest bikes, the ones that break 200 mph.

You have to race for years in lower classes of motorcycles before you're allowed to enter the Senior TT. The race was stopped for an hour before the announcer even gave news of his condition, or any details of the crash. It was a long hour. People didn't look exactly ashamed that they were cheering on this race not long before, but it wasn't far off. Grey and anxious and concerned.

The Isle of Man itself is a very small place. "A rock in the Irish sea with 80,000 alcoholics," one local called it. There aren't a lot of hotel rooms, so some families put up racers in their homes. Every local I talked to seemed to know a rider one way or another. Deaths aren't brushed away here; they're mourned.

Given the loss of life that happens each year, it's only natural wonder why the race is still allowed. The locals wonder this too. There are fears that the race could get shut down any year. It's one thing for the riders to die, but if a spectator was killed, or if there was a particularly horrible series of wrecks, the TT could be resigned to history. And it's not like the motorcycles running in the race are getting slower each year — quite the opposite. One has to imagine if the day will come soon when the bikes will be too much for these old roads.

But much as the the TT races already feel like part of history as it is, the event has been "out of its time" for nearly a quarter of its existence. The Isle's tourism board took over the management of the races back in 1989, presumably starting the event's current trajectory towards increasing international attention even as the race stays very much un-sanitized and pre-modern.

The more I spoke to people about the races in the face of their danger, the more I was left with a lot of double talk. I expected a kind of nihilistic bravado from the actual entrants of the race. McGuinness did once refer to TT racers as "a bunch of hard-nosed bastards," after all. The TT does have a certain kind of cultish magnetism, an embodiment of some pent up self-destructive desire to ride so fast the wind tears you to shreds.

But the riders said they weren't going because they thought they might die. They said they went specifically because they believed that they would survive and finish and succeed.

And then just as quickly as they started to affirm the living spirit of the race, they also talked about the "moments" they've had out on the course. When death was a few inches away. When they scraped that curb they were only supposed to graze. Ride along with them and they'll readily point out each and every corner they know where another rider, another friend, ate it.

It's the same with the locals. Their voices turn somber when I bring up death, but then they'll turn around and tell you horror stories from when things go wrong on the TT. Midair impacts turning humans into rag dolls. Body bags on front lawns. Guts spilling out of chests. What I heard from a mechanic whose son runs in amateur auto races on the Isle — forget horror, they sounded like war stories. They're anxious as the rest of us, maybe unsure of their role in this deadly circus.

But they keep showing up every year, all in a way that defies any sort of logic. The tourists, the sportbike pilgrims, the locals, the racers. The momentum keeps rolling along, like a tire skipping across a cat's eye at 200.

Photo Credits: Raphael Orlove

Top illustration credit Sam Woolley

Contact the author at raphael@jalopnik.com.