One of the things I adore most about cars is how gleefully irrational they are. As far as functional machines created by humans go, automobiles may have the greatest ratio of engineering effort expended to effectively useless functions of anything. That’s what makes them great! Whether it’s absurdly complex hidden headlight systems or a way to turn your car into a $75,000 whoopee cushion, humans have proven our willingness to expend absurd amounts of resources and energy to have our cars do absurd things. Like how, in 1960, Cadillac designed a car that could stab you in the back unless ridiculously complex engineering was involved. I’ll explain.

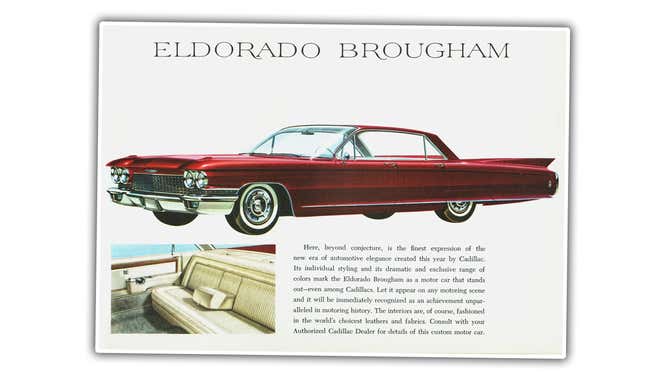

The Cadillac I’m talking about here is a very special one; only 107 were built, and at the time they were nearly as expensive as a Rolls-Royce. This is because the Cadillac Eldorado Brougham had a hand-built body by Pininfarina, and it was the design of this elegant, tailored-looking body that demanded the unusual engineering efforts.

See that long, sleek, trim design, with that incredible, impossibly lean looking greenhouse, lack of a B-pillar, and what pillars are there being so lithe and thin? See how the roofline cants down just a bit at the rear? See how lovely and airy it all is? Of course you do.

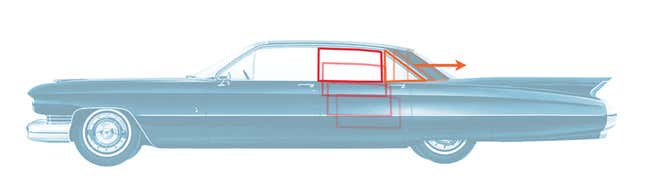

Now, pay attention to the area I have circled there, where the rear window meets that little triangle of glass by the C-pillar. That area is important, because this is how it behaves when you open that rear door:

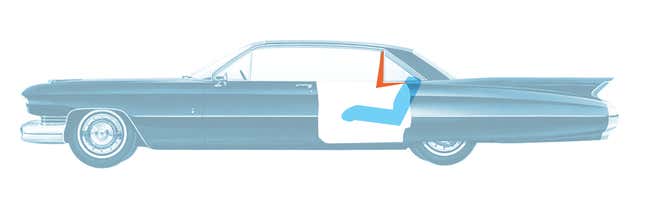

Did you see what’s going on there? When you open the door, that little triangular bit of glass slides rearwards, and it also does that when you raise or lower the rear window, because that rear window needs to drop down into the door on a diagonal, because it’s too big to just drop straight down.

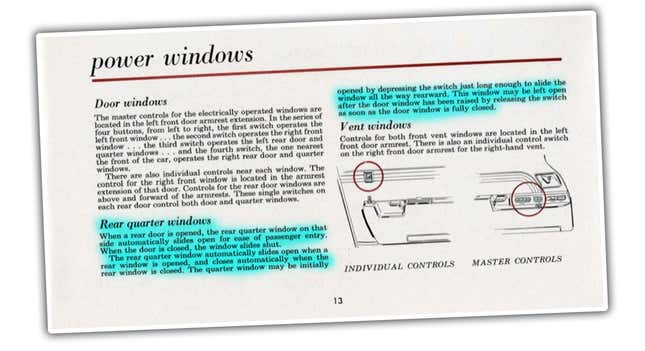

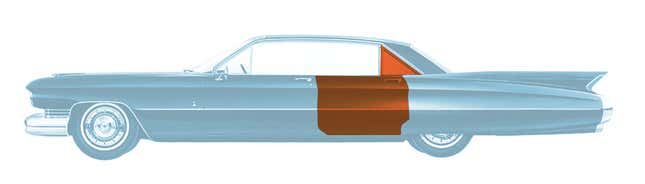

To pull all of this off requires a staggering amount of engineering and hardware, at least for a door window. It’s an extra electric motor and related gearing per door, plus a much more complex rear window raising and lowering system. And you have to do it, because if you just left the window in place, it would become a sharp glass-and-steel dagger, ready to stab you right in your tender, meaty back:

Of course, the owner’s manual puts it in more genteel terms, “ease of passenger entry,” which is automaker PR-talk for “no perforated kidneys.”

What’s so baffling about all of this is how seemingly easy it could have been avoided. For example, why couldn’t the door itself have included the vent window in it?

If the vent window was part of the door, then it wouldn’t need any special motors or anything, and the passenger would have had just as much access to enter?

Now, I’m not sure if this would have solved the issue of the rear window needing to drop down at an angle, but you know what would have? Designing some doors that allowed the windows to just drop straight down.

Other cars managed to do just that, even pillar-less ones with no door frames like this Chrysler, for example:

It wouldn’t have had to detract from the design hardly at all, I wouldn’t think; it’s not like the rake of the rear would have had to be compromised much at all.

But that’s not what happened. There’s likely many, many design and engineering solutions that could have eliminated the need for this head-shakingly complex window system, and they could have all started from the moment where the designers realized that people getting in the back of the car would have to navigate around a sharp glass pizza slice.

Someone could have said, “Hey, that’s not gonna work; let’s take another crack at that door design.” But no one did. Instead, they told some engineers, “Hey, this door design could poke people in the back with a corner of glass—why don’t you fellas come up with some kind of Rube Goldberg clockwork madness to get that thing to move out of the way and then come back into place? Use whatever you need to! Don’t worry about money!”

It’s amazing to me that this decision was made, but I have to admit, I love it. Faced with a choice between the designers dream design and the grim realities of the physical world, Cadillac chose drama.

Because, really, that’s what this window adds—the precise dance of that glass moving out of the way so you may enter the car with grace and ease is makes opening that rear door an event, not just the thing you have to do if you’d prefer to be inside the car instead of out.

That, that right there, that absurdity and madness and effort and uselessness and perhaps silly flair for spectacle, that’s what makes cars so great.

(thanks, Hans!)