One of the most fascinating things about automotive engineering is the ways manufacturers go about reducing vehicle cost. Platform sharing, “badge engineering,” and strategic partnerships are some of the big cost-reduction schemes, but perhaps my favorite method is the jankiest one: Simply placing your badge over another one. I call it “coverup engineering,” and it’s been happening for decades.

I guess you could consider “coverup engineering” a version of “badge engineering,” except instead of removing another car’s badge and replacing it with a different one (and maybe tweaking the fascia a bit — see Scion FR-S/Subaru BRZ, Mazda Tribute/Ford Escape, and a slew of others) an automaker doesn’t even remove the old badge. The carmaker leaves the whole component as-is, and simply hides the old emblem with another one.

My favorite example is one I learned about recently after a 1964.5 Ford Mustang owner posted to a Mustang Facebook group what he found when he removed his pony car’s steering wheel center cap:

Another person on the Mustang Facebook confirmed these findings, posting what he himself spotted when he removed his steering wheel cap:

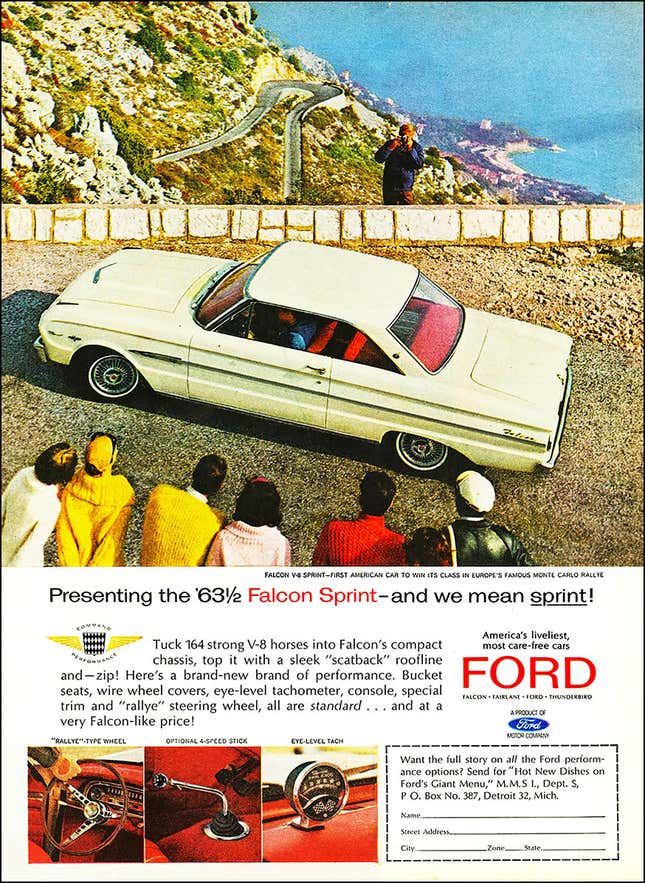

Mustang fans will probably think: “Aha! That makes sense, as the 1963.5 Ford Falcon Sprint acted as the basis for the first-generation Ford Mustang.” Indeed, back in 1963, Ford took its humble, compact Falcon and brought it upmarket a bit, shoving the mid-size Fairlane’s 260 cubic-inch V8 under the hood, prettying up the interior, and bolting on a tighter suspension. When the Mustang launched in April of 1964, it was almost exactly just a Ford Falcon Sprint with a different body.

You can see the Mustang-like steering wheel in this old Falcon Sprint ad:

The fact that Ford just stuck a new badge over top of another model’s just amuses me to no end. It’s so lazy, but at the same time, it makes for a fascinating “easter egg” when you take the vehicle apart.

This sort of cost-saving still happens in the modern era. Watch this video by YouTuber DrivingCars showing someone taking an S-badge off of a Seat Cupra 300's 2.0-liter TSI’s engine cover. This reveals a VW logo, which makes sense, as the same engine is found in the Golf R, and the Wolfsburg-based automaker uses versions of the engine in a number of other vehicles.

A subset of “coverup engineering,” though not as blatantly bamboozling, involves automakers using parts developed by other brands, but in areas that customers don’t often see. I don’t find it as amusing as literally placing a badge over another, because there’s something about the bold subterfuge that I almost respect, but I have to say that sliding under my 1979 Jeep Cherokee Golden Eagle and finding General Motors branding is pretty cool:

That TH400 transmission oil pan above reads: “Hydramatic Div of GMC.”

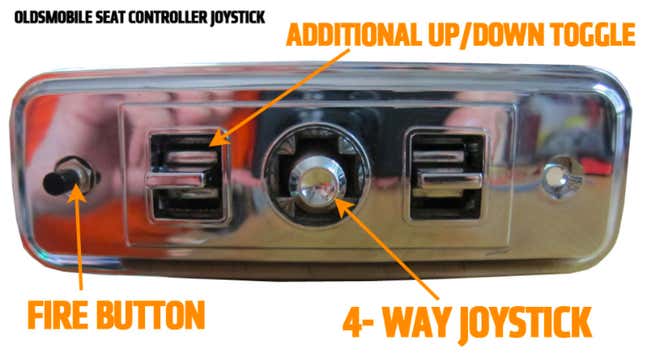

Also a subset of coverup engineering is the power seat controller (shown above) that my coworker Jason Torchinsky wrote about. He tells me that over top of the chrome you see there was another, larger chrome bezel simply placed over top. Clearly this was to allow for aesthetic variation in the same part.

I myself wrote about how Jeep employed a similarly clever tactic, covering up the first-generation Jeep Wagoneer/Gladiator’s whole face with new grilles. In fact, as late as 1991 you could take the grille off the Grand Wagoneer to reveal the former class-A surface that once was the 1963 Jeep Wagoneer’s face.

Anyway, I wrote this article after spotting a Facebook post about that Ford Falcon steering center cap under the early Mustang emblem, and deciding that you, dear readers, needed to know that random fact. Plus, I wanted to establish the term “coverup engineering,” though if there’s a more precise word for this practice, let me know.