You're Wrong About The Yugo

The pop culture view of the Yugo is built around a cheap Boomer joke that ignores history and context.

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

"Objective truths" are few in the automotive world, but the ones that do exist transcend our hobby to permeate the world at large. For example: Hummers are driven by comedically macho—or hilariously insecure—men with a need to project strength; BMW drivers don't signal and drive like lunatics. And, of course, the Communist Yugo is the worst car ever made, remaining a convenient three-door shorthand for political failure more than three decades after it left the U.S. market. Fighting any of these stereotypes is an uphill battle at best, and an automotive writer staking their reputation on a defense of the Yugo is something few would attempt.

Here is my defense of the Yugo.

Tito’s Car

To fully understand the Yugo, we need a brief history lesson on the country that birthed it. The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, home to the Zastava Automobile company that built the Yugo, was a Communist country established after World War II that was made up of six constituent republics with unique ethnic and cultural backgrounds: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia. Yugoslavia's politics were made drastically more treacherous thanks to widespread economic disparities and nationalistic fervor in those six member republics.

One force kept the country largely united for most of its history: Josep "Tito" Broz, the charismatic leader of Yugoslavia from its inception in 1945 until his death in 1980 at age 87. He maintained strong autocratic control over the country throughout his 35 years at the helm (the New York Times said he "goverened like a monarch" in his obituary). He led with a combination of statesmanship, strongman rule, and a governmental policy of "Brotherhood and Unity" that placed Communist ideals of decentralization and comradery above ethnic or cultural divisions, and Yugoslavia enjoyed relative peace and massive improvements in the standard of living under his leadership.

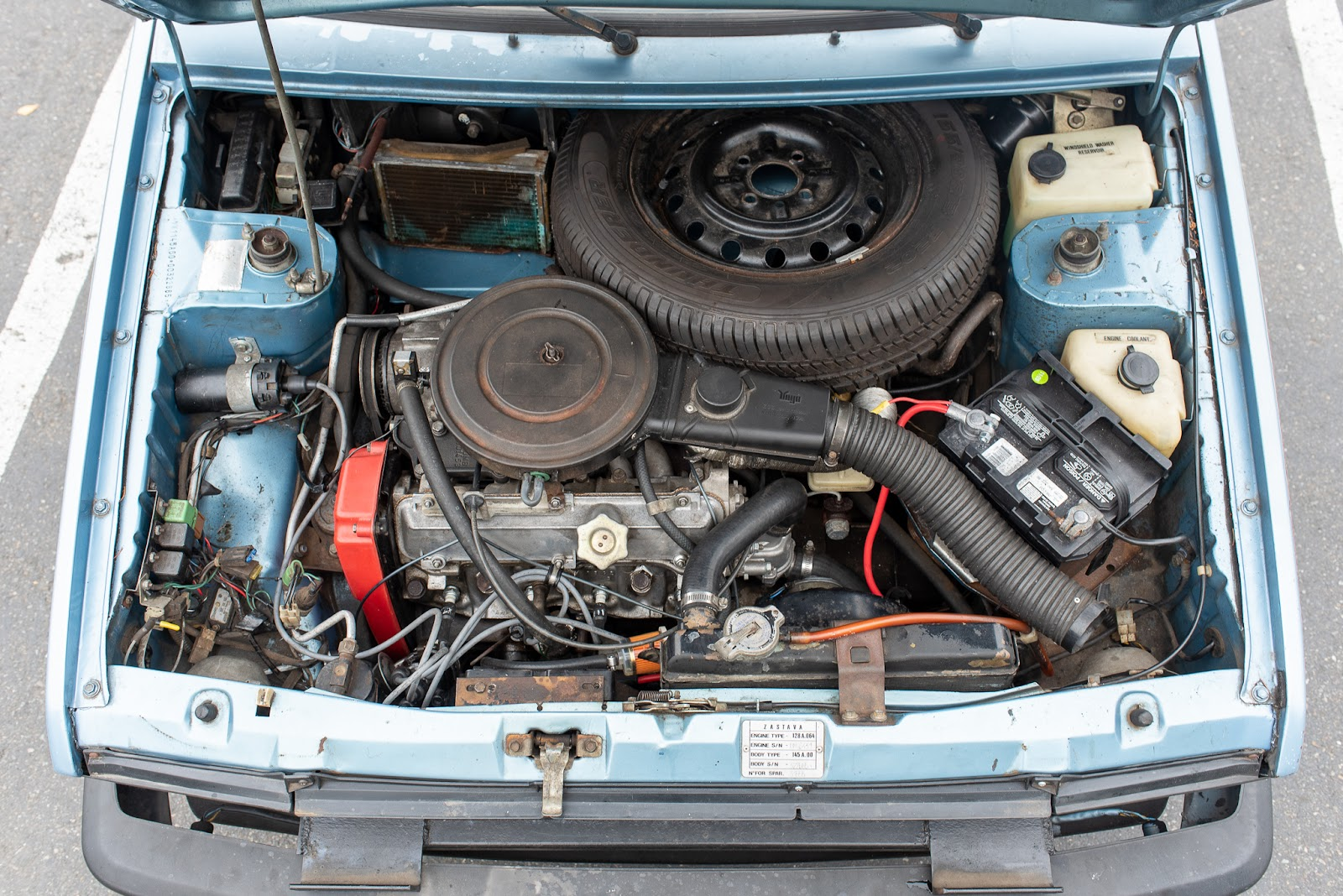

The Yugo was Yugoslavia's attempt at nation-building in the form of a humble hatchback. In 1978, two years before Tito's death, the Zastava Automobile company presented the leader with a concept car based on the built-under-license Fiat 128. This new proletarian hatchback was meant to be the pride of the Yugoslavian auto industry; low cost of ownership and practicality were key, and Zastava hoped these characteristics would allow the new three-door to flourish not just domestically, but all throughout Eastern Europe. Because it was meant to be the crown jewel of its homeland, all six member republics of Yugoslavia contributed to Yugo production as a means of encouraging national unity. Electrical components came from Slovenia, interior bits arrived from Croatia, Bosnian factories would build engine parts, Macedonia supplied trim and mirrors, and a Serbian plant would put it all together. The new hatchback would be a physical manifestation of Tito's Brotherhood and Unity.

Unfortunately, that vision never came to fruition. Tito died on May 4th, 1980, and Yugoslavia shortly proved unable to continue without him. The country, already beginning to struggle economically while Tito was alive, rapidly fell into severe recession after his death; by 1982, Yugoslavia's inflation rate was 40 percent. By the late 80s, 60 percent of the country's population under 25 was unemployed. In the economic chaos and leadership vacuum left by Tito's death, ethnic nationalism rapidly took root, and in 1992, Yugoslavia collapsed into a decade-long civil war.

The first Yugo rolled off the production line just a few months after Tito's death, in November of 1980. With the country already showing signs of trouble, the humble hatchback was born under a bad sign, never able to live up to the ideals of Brotherhood and Unity that inspired its creation.

This Is a Car Review, I Promise

Despite Tito's death and the unstable economic situation that followed, the Yugo actually enjoyed modest homeland success in its first decade of production. The humble car was only brought to American shores in 1986, when automotive entrepreneur and industry maniac Malcolm Bricklin (of the eponymous Bricklin SV-1), searching for his next business opportunity, met with Zastava Automobile to bring the Yugo stateside. The business case was simple: This would be the cheapest new car money could buy. Even after modifying the Yugo to meet American safety and emissions standards, it still nabbed that title by a broad margin. In 1986, the average new compact car cost right around $11,000; the base-model Yugo GV landed in showrooms that year with an MSRP of $3,990. (That translates to right around $11,000 in 2022 dollars; the cheapest car currently on sale in the U.S. is the Mitsubishi Mirage ES, which starts at $16,990.)

For that low price, the Yugo promised relatively efficient operation from its transverse 1.1-liter carbureted inline-four that spit out 55 hp and achieved 26 MPG combined. That was, admittedly, all it promised at that price, but it was enough to sell over 140,000 cars in seven years of U.S. sales. Buyers seemed to enjoy the car for what it was, with one Popular Mechanics survey recording generally favorable responses about the ownership experience, though dealers were apparently atrocious and price-gouging was rampant, with some customers reporting that the owner's manual was sold to them as a $75 option. Still, about 80 percent of Yugo owners reported that they would consider buying another Yugo. Could this much-maligned Communist intrusion into Reagan's decade of unfettered capitalism really have been all that bad?

And so, 35 years on, I hopped into this mechanically-mint '86 Yugo GV to see if things were as dire as all the stereotypes had warned.

Alright, It’s Not Winning any Awards for NVH

One thing period reviews got right about the Yugo is that, yes, it is cheap upon first contact. The interior reminded me of a plasticky version of a first-generation Honda Civic, with its parts-bin gauge cluster (consisting of a speedometer, a fuel gauge, and a variety of warning lights) taking center stage behind the flimsy two-spoke steering wheel. Notably, the plastics used in the interior seemed more durable than most from the era; only the U.S.-specific center console showed a distinct yellowed-electronics hue developed over years of sun exposure.

Period reviews also ragged on the Yugo for unacceptable fit and finish, but this 35-year-old Yugo's panel gaps weren't any worse than other economy cars of the era. It also, somehow, still had an uncracked dashboard cover and untorn (and relatively comfortable) seats, unlike a lot of more expensive Japanese cars of the era I've driven. Score one for the Yugo's longevity, then.

In motion, it was loud, and the thin body panels didn't lend much isolation from the buzzing 1.1-liter just ahead of my feet. That motor I can only describe as "sufficient." I wasn't going to win any stoplight drags, but 55 hp was plenty to whip around the scarcely 1,800-pound curb weight of the Yugo. The four-speed manual transmission indeed changed gears, although it was the only part of the car I found verging on unacceptable; the 2-3 shift had all the confidence of the average British citizen evaluating their present government. Handling was there, assuredly, as when I rotated the steering wheel, the front wheels turned and the Yugo aimed itself in the general direction I wanted to go. I didn't attempt to find its demeanor at the limit, because it's a Yugo.

All of this is to say the Yugo is honestly rather average. Through a modern lens, most old economy cars seem desperately noisy and horribly slow; my first college car, a '92 Mitsubishi Mirage, wasn't much quieter or well-appointed than the Yugo, and despite my belief that I could be Kent State University's resident Tommi Makinen in my tri-diamond coupe, the Mirage didn't handle a whole lot better, either. The Yugo feels and drives like a typical forgettable economy hatch of its era; it's a lot more Chevette than Civic, but for the price, it's hard to hold much against it. This car was cheap enough brand-new to cross-shop against dire used holdouts of the Malaise era, and truthfully, against those machines, it holds up well.

All things considered, the Yugo is not bad—so why do people revile it so much?

The End of History and the Last Yugo

For one, the Yugo's stateside run came to a bleak and ignominious end in 1992, when the United Nations sanctioned the former Yugoslavian member states in response to the atrocities of the Bosnian War. Exports of goods, including Zastava Automobile's Yugo, were halted. The U.S. dealer network evaporated, and crucially, parts supplies rapidly dried up. This would be a problem for any car, but the Yugo GV was especially susceptible to parts shortages: its Fiat-sourced engine was an interference design, with a timing belt that had to be changed every 40,000 miles. With the dealer network gone and spare parts nonexistent, most Yugos in the U.S. succumbed to neglect. As it became impractical to maintain and repair the $3990 cars, their reputation for reliability tanked.

By contrast, in the car's homeland, where parts and knowledge remained abundant, the Yugo maintained an image of steadfast reliability. Production continued until 2008, despite NATO destroying the Zastava Automobile factories with a bombing campaign in 1999. In the end, Zastava built almost three-quarters of a million three-door hatchbacks over the Yugo's 28 years of production.

What ultimately made the Yugo a punchline in America, I believe, is that it is so communist. As perestroika gave way to the ultimate collapse of the Soviet bloc, Americans believed themselves to be at the end of history, with society reaching its final form as Western liberal democracy overtook the globe. Although Yugoslavia famously chose not to align itself with the USSR after Tito's personal rift with Josef Stalin in 1948 and the country maintained friendly ties with Western leaders, to the average Western automotive writer, Yugoslavia's collapse was just another example of the inevitable failure of Communist ideology. The victors of the West believed the capitalist democracies of the world would benevolently rule until the sun's light burned out, and Yugoslavia—and the Yugo itself—were definitionally doomed. Never mind that the Eighties were littered with horribly unreliable boondoggles of engineering that humiliated auto industry giants; the Yugo simply had to have failed, because the ideology that created it was so fatally flawed.

As it was built, the Yugo would never have won awards for anything beyond, perhaps, "cheapest car." But the vision of a Model T or VW Beetle for the eighties was a compelling one; it just fell short thanks to the eventual collapse of the society—and the ideals—that built it. Thirty-five years on, the last few running Yugos left in America make a compelling, if tragic, case for what "Brotherhood and Unity" could have been.