Words Apparently Matter When It Comes To Car Crashes

The headline on this blog used the word car "crashes," not "accidents," because words matter. That is the conclusion of a study conducted by researchers from Texas A&M and Rutgers University about how "minor changes in crash coverage can shift a reader's perceptions of what happened and what to do about it."

To test this, researchers asked 999 randomly selected people (yes, it bothers me they couldn't get one more person, too) to read one of three accounts of a car crash involving a pedestrian.

The first was "pedestrian-focused" and reads most like what you might find in your evening news or local paper if you still have one. In this account it was an "accident" and the police responded to "a pedestrian struck by a car...wearing dark clothing." The second article was "driver-focused" in which the fatal "crash" involved "a driver striking a pedestrian." The third, a "thematically-framed" approach, was similar to the driver-focused one but added a paragraph of context about the increasing number of pedestrian deaths on a road with high traffic speeds and few streetlights.

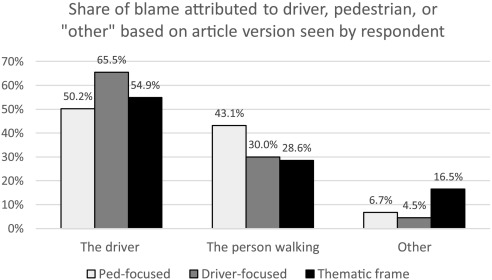

Here's how the respondents assigned blame for the crash, broken down by which article they read:

Those who read the pedestrian-focused account were, unsurprisingly, far more likely to blame the pedestrian and least likely to blame the driver. The same holds true for those who read the driver-focused account. Perhaps most interestingly, those who read the thematic account, and therefore understood the larger context in which the crash took place, were far more likely to blame "other" factors.

Although the researchers don't say precisely what those "other" factors may be, we get a clue elsewhere in the study. Those who received the thematic frame were more likely to support infrastructure changes (93.4 percent) than those who received the pedestrian or driver-focused versions (85.3 and 85.2 percent, respectively).

The researchers are not saying that journalists and others describing crashes should start automatically blaming drivers, but people should be aware that the language they use often gives readers the improper impression pedestrians are to blame.

"At the moment, the default setting is for crash coverage to blame the pedestrian," the researchers noted, citing several studies to back up their claim. There are good journalistic reasons to avoid this practice; mainly, those reporters rarely have actual evidence the pedestrian was to blame. "Despite the lack of evidence," the researchers noted, "writers rarely break from the practice of blaming the victim."

Instead, it is the reporter's goal to describe what happened and make the public aware of the circumstances that caused the crash. Often, neither driver nor pedestrian was breaking the law, because we have a lot of crappily-designed roads that invite or even force conflict between road users.

"In short, if the goal is to call public attention to external circumstances that cause road deaths, thematic framing helps to accomplish this goal," the researchers concluded. In other words, context matters, and readers get that. We'd all be better off if more journalists included it.