Why The Datsun 510's Hood Prop Rod Was Perfect

One car part that hasn't changed much in many decades is the prop rod—yes, the metal stick that holds your hood up while you try to figure out where the heck all that steam is coming from. Still, there are quite a few variants out there, some better than others, which is why I'm here to show you my favorite prop rod design. I discovered it under (and on) the hood of a Datsun 510.

While in Germany on a business trip involving Motor Works of the Bavarian variety, I stopped by my friend's awesome garage near Nuernberg, and drooled over his incredible Datsun 510, which is currently down for repairs as my friend struggles to source front drum brake parts. Among the many interesting attributes that I spotted on the legendary machine is its hood prop mechanism, which is simple and lovely:

The prop rod rotates about a cross-car axis defined by a bracket screwed to the top of the center of the firewall. The rod is spring-loaded such that it has a tendency to point its other end upwards toward the sky. That other end sits inside a slot in a bracket attached to the bottom of the hood. The slot has a notch in it that—when the hood is open—prevents the rod from sliding, and thus keeps the hood from closing.

To shut the hood, you just lift the hood a bit so you can pull the hood-end of the rod off the notch and toward the front of the car, thus rotating it against the force of the spring. Then you lower the hood, and the hood-end of the rod slides along the slot. With with the hood fully closed, the rod sits flat, just above the little 1.4-liter inline-four engine.

I'm a fan of this setup because the rod is small and out of the way, and because it's simple. Obviously, it's not perfect, since I bet the spring could theoretically wear out over time (though this Datsun is from 1972, and I bet that's the original hood prop spring). Also, on a car with a larger engine, reaching the back of the hood to pull the prop rod out of the notch in the slotted bracket could be difficult. Plus, I don't suppose this is the cheapest setup, since it requires big brackets on the hood and firewall, as well as that spring. Plus, since the prop acts near the hood's hinge, that hood has to be pretty stiff near that slotted notch.

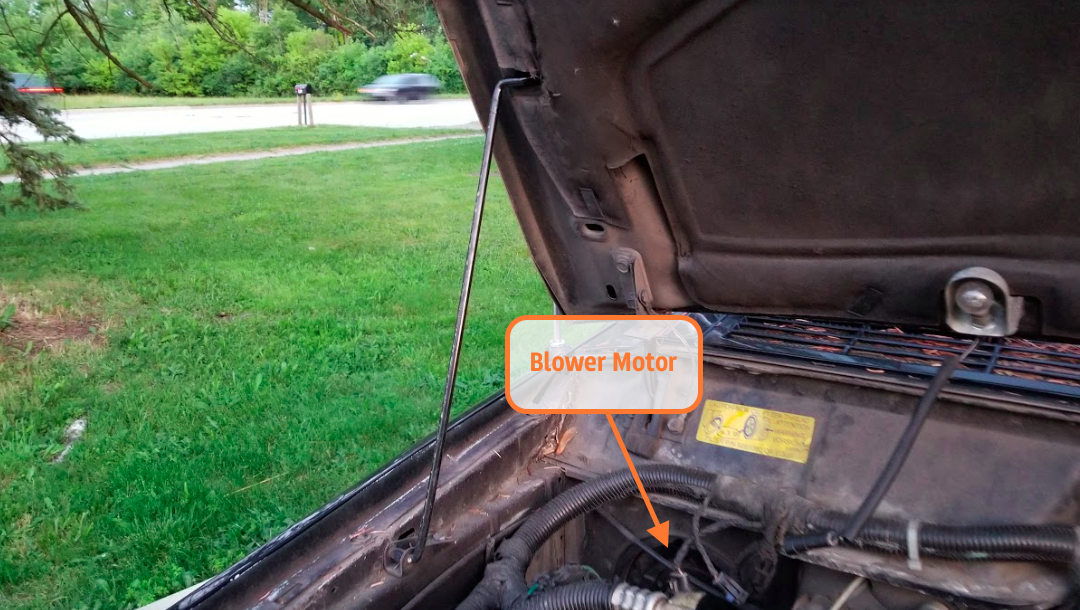

Still, it's basic, small, will last forever and, most importantly, it's out of the way. That's more than I can say about most designs. For example, here's the hood prop setup on a Jeep Cherokee XJ:

The prop rod hinges about a small bracket bolted to the inner fender on the passenger's side. To hold the hood in the open position, you simply grab the top end of the rod (which sits toward the front of the Jeep) out of its small holder (I'll show that in a moment), rotate it upwards, and jam its tip into one of two holes in the hood.

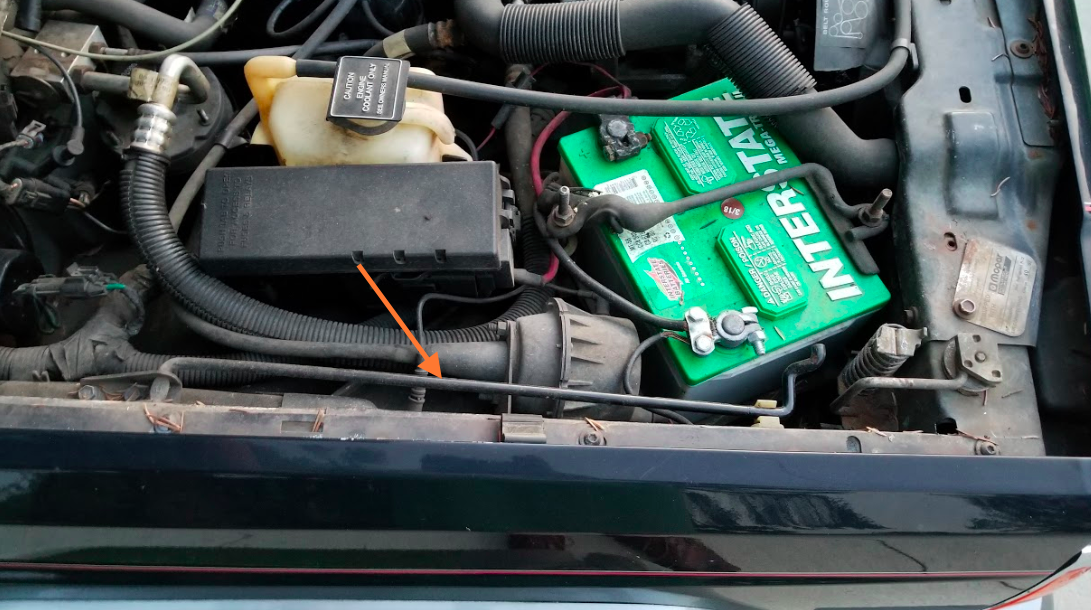

When the hood is closed, the rod runs parallel to the car's fore-aft axis (which many automakers refer to as the x-axis) and sits like so:

This setup is decent but not perfect. For one, that little plastic piece that holds the prop rod in the down position breaks quite easily (though Jeep later changed the holder to steel), and secondly, this rod does take up a bit of under-hood packaging space (though, in fairness, the Datsun's design does, too—just above the engine).

My biggest issue with the XJ's hood prop setup is that it can get in the way of wrenching, particularly when I'm working in the rear left corner area (for example, if I were trying to replace a blower motor, which I've pointed out in the image just before the last one).

Still, I like that the XJ's hood holes give me two hood angle options, since I'm sometimes feeling lazy, and don't want to open the hood all the way. Plus, the design is dead simple and probably dirt cheap.

A number of cars, like the totaled Kia Rio that's been festering in my backyard, store their prop rods along their radiator support crossmembers. In other words, with the hood closed, the rods axis is parallel to that of the cross-car axis (the y-axis).

This design, I would imagine, is inexpensive as, like the XJ, it just uses a basic bolted bracket on one end and a plastic rod-holder on the other. As for when the hood is open, the non-hinged side of the rod just pokes into a hole in the hood.

It's fine, but my biggest qualm with hood props that hinge about a bracket on the radiator support is that they really block the engine bay. Just look at the image above; any work that I do on the right side of that motor will involve me having to work around that steel rod, which is a pain in the ass.

The current Jeep Wrangler hood prop rod design is the "inverse" of the design above, in that the rod is stored on the bottom of the hood when the engine bay is closed off, but when you want to service your engine, you just grab the non-hinged end of the rod from the front of the hood, pull it down, and pop its end into a hole in the radiator support crossmember.

It's fairly basic and probably cheap to build. Plus, it lets you use the rod to push the hood wide open. Sadly, that damn prop rod is still in my way.

To be fair, the Wrangler also offers perhaps the single greatest hood propping option of all: simply leaning that hood against the windshield.

This was the only hood-prop option on early flat-fender Jeeps, and it works well, especially if you want to pull the engine straight up and out using a hoist. The setup does require walking around the side of the vehicle to gently lay the hood against the top of the windshield, and also, there's nothing really stopping the hood from falling other than weight of the hood itself. So who knows—perhaps if wind hits it at the right angle, it could fall? I've never had this issue, and with the windshield blocking the wind, it's probably fine.

But no, we're not done talking about hood prop designs, because I've got some bones to pick. Particularly with automakers who used the hood hinge mechanism found on my 1987 Jeep Grand Wagoneer (shown here) and on a number of older cars like my brother's 1966 Ford Mustang.

These old cars don't actually have prop rods, and their hoods don't even hinge about their cowls. Instead, the hoods are bolted to a spring-loaded contraption made up of rotating arms connected to a bracket attached to the inner fender.

In some ways, it's a nice design, since the hood stays put at whatever angle you open it to. And also, I bet there are some practical advantages to the fact that the hood moves forward as it opens, and slowly drops on top of the cowl from above as it closes. Still, I hate these types of hinges, since they have a tendency to seize up, leaving me with no way to get my damn hood open without breaking something. Even when they do work, the spring tends to make noise when opening the hood, and that hood doesn't open nearly far enough, so working on the back of my engine becomes a pain in the ass.

Nearly as bad is the strut setup, shown here under the hood of the extremely underrated 2016 Chevrolet Impala, but also found on a number of higher-end modern cars.

In some ways, it's great: the hood requires very little effort to open, since the gas strut does all the work. Plus, this particular setup is out of the way, so it won't be an issue as you make under-hood repairs. Even closing the hood is not a huge deal, despite the fact that you're working against the gas strut.

No, the problem with this setup is that when it fails, as it tends to do after a few years, you've now got a heavy hood trying its darnedest to make every under-hood operation a true nightmare. Many of my friends end up using a piece of wood as a prop when the strut fails, but that's a bit dangerous, since the wood sits precariously somewhere on the hood on one side and in the engine bay on the other. And while, sure, my buddies could just buy new struts, nobody wants to service their damn prop rod. Folks are already under the hood repairing an important engine component—they've got bigger problems.