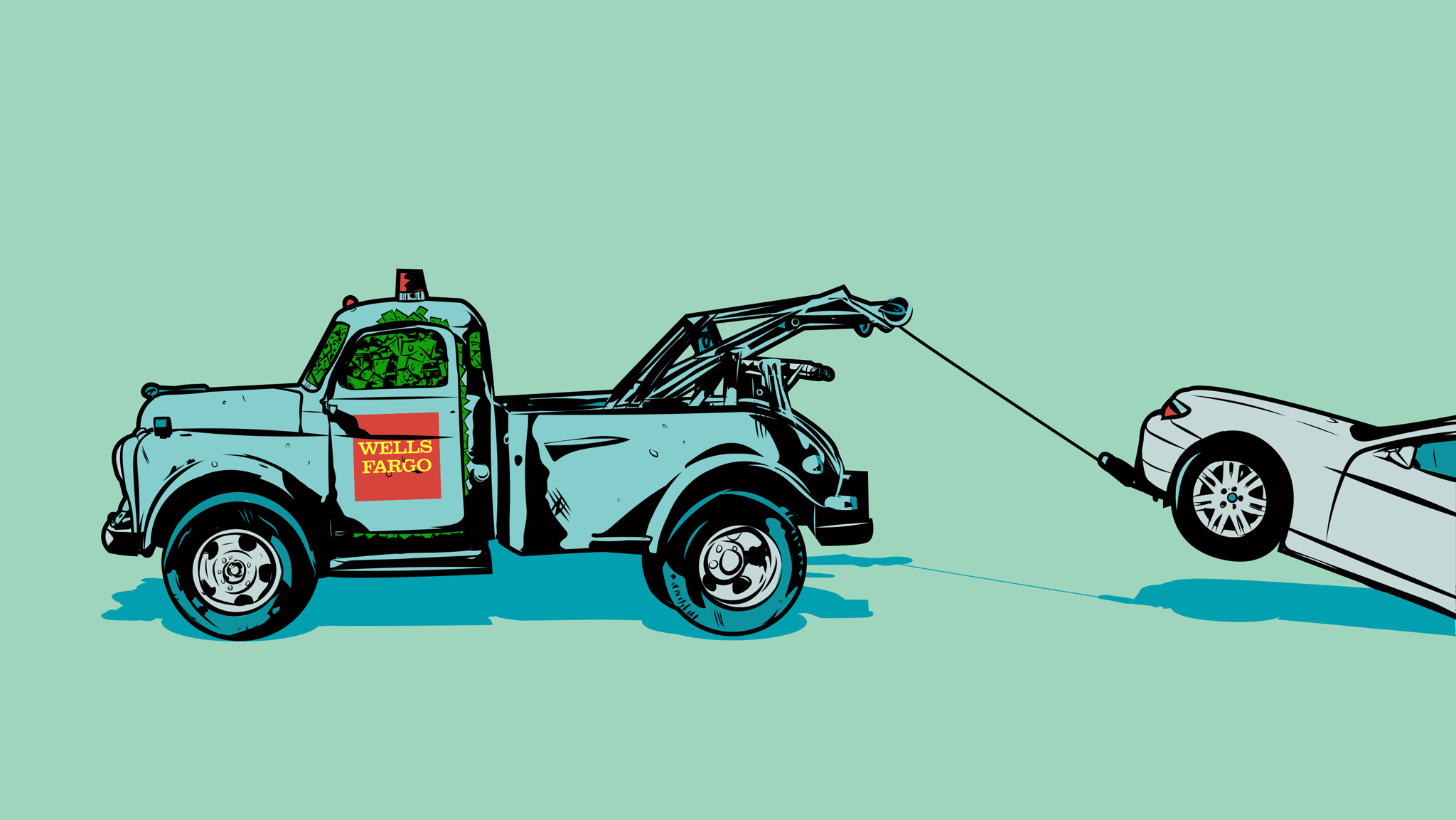

How Wells Fargo Screwed $80 Million Out Of Customers Using Unnecessary Car Insurance

A week after New York resident Juan Thomas bought a 2004 BMW 745i, in December 2012, the bank that financed the purchase—Wells Fargo—contacted him to say that he needed additional auto insurance for the vehicle. This was a bit odd, mainly because the car was already insured. "It didn't sound right to me," Thomas said. A month later, he heard again from a Wells Fargo representative, who again claimed his car wasn't insured. Soon after, he received a bill and found that Wells had placed a collateral protection insurance policy on his account.

"From then on, my [cost] just kept going up going up," Thomas said in an interview. He repeatedly spoke with Wells Fargo representatives, sent along proof of his insurance, but nothing changed. With the insurance, Wells increased his monthly payment from $413.48 to about $600, at first, to, eventually, $1,000.

"It seemed like I was never going to get out of debt for this car," Thomas said.

Thomas, 55, is one of roughly 800,000 people who were affected by a scheme from the bank that involved forcing customers to purchase auto insurance they didn't need. The San Francisco-based company has since apologized, but only after the scandal was revealed in July by The New York Times, which obtained a 60-page internal report on the situation that was prepared for Wells Fargo executives.

The four-year period that was covered by the report found the scheme impacted hundreds of thousands of consumers, and interviews and court records reviewed by Jalopnik recently show just how much of an emotional toll it has taken on them.

Wells has previously said that a review of the collateral insurance program was launched in June 2016, following a string of customer concerns, and the program was discontinued a few months later. But revelations of the scheme didn't emerge until the Times report was published. A spokesperson for Wells declined to provide a copy of the report and Oliver Wyman, the consultant firm that prepared the review, didn't respond to a request for a copy.

The four-year period that was covered by the report found a scenario that impacted thousands of consumers, according to the Times, with an estimated 274,000 becoming delinquent on their account, while around 25,000 vehicles were wrongfully repossessed. In addition, some 60,000 customers who live in states where banks must inform consumers if insurance is imposed were never properly notified.

Wells has since disputed its own numbers cited by the Times. The bank has said it later determined that 570,000 customers may qualify for a refund, and that the insurance scheme led to only about 20,000 repossessions.

Yet, those are still huge numbers, and Wells has said it plans to reimburse $80 million in total for remediation.

For Thomas, that relief isn't enough. Five years on, he's still making payments.

"The credit that they're giving me, it doesn't add up to the money that I sent," he said. Thomas filed a lawsuit last week against the company in federal court.

A Wells Fargo spokeswoman declined to comment on the suit, and described the Oliver Wyman report as a "preliminary" step toward determining "who was going to be a part of the remediation."

"We shared our remediation approach with regulators and we continue to engage with them," the spokeswoman said. "We are continuously reviewing our accounts and reviewing the issue as its an ongoing remediation."

"This was a breakdown in internal controls," she added.

‘What Are You Talking About?’

The trouble for Thomas started soon after he bought his BMW in late 2012.

The 7 Series caught his eye while surfing the Internet one day, he said. Thomas called the dealership in New Jersey listing the car, and, soon after, he was cleared to purchase it.

"So me and my brother rode up there to see if it's true," Thomas said. Sure enough, the car was his with a $2,500 downpayment. He signed a contract for a 48-month loan that was financed through Wells Fargo Dealer Services, with a monthly payment of $413.48 beginning in February 2013. All in all, not a terrible deal for a used flagship BMW sedan.

A week later, Thomas said, the frustrating calls began.

"I got the car registered and all that kind of stuff," he said. But the bank told Thomas he needed collateral insurance. "I was like, 'Well, I have collateral insurance, what are you talking about?'"

In the intervening months, Thomas said he spoke with innumerable Wells Fargo reps and sent proof of his insurance, to no avail. Thomas felt the bank-purchased policy was bogus and refused to pay the additional amount for the insurance, according to his lawsuit.

By not paying the additional cost, late fees racked up. Thomas said the 48-month terms have been extended by years, costing him above and beyond what he was initially supposed to pay, all the while hurting his credit score.

And if Thomas wasn't calling the bank to try to resolve the issue, Wells tried to chase him down to get the full payment, he said. Calls came at all hours of the day.

"It was like they were playing games," he said.

How It Worked

Contracts that customers sign for an auto loan with Wells require them to maintain "comprehensive and collision physical damage insurance," the company said in a July statement. If Wells found there was no evidence that a customer already had insurance, the bank was contractually allowed to purchase collision protection coverage for them.

The insurance was provided through the company's Dealer Services unit, which says that Wells has more than four million auto finance customers. The dealer unit makes it plain in writing what a customer should expect if Wells purchases auto insurance on their behalf: the coverage "may be considerably more expensive than insurance" obtained elsewhere.

The lender-placed insurance began in early 2006, and National General Insurance underwrote the policies. Wells is unusual among major financial institutions for providing lender-placed insurance, the Times reported. Bank of America and JP Morgan Chase, for instance, don't offer similar policies.

When customers bought a car through Wells, their information would be sent along to National General, the Times reported. The insurer was supposed to confirm if an owner already had coverage—and if they didn't, the collateral insurance would be immediately added to their account.

If a customer called the bank to ask about why they were receiving a redundant charge, and had proof of adequate insurance, the policy was supposed to be canceled, the Times reported. Wells then should've provided a credit to their account.

But, for whatever reason, in many cases this didn't happen, and it was a situation that wreaked havoc on customers who automatically had their payments deducted from a bank account, as many might not have been aware that their payments were rising at all. The internal report found that many customers didn't contact Wells about the extra insurance.

It's also unclear why the situation was prolonged for so many years. Wells said the internal review found that "certain external vendor processes and internal controls were inadequate," leading to extra premium charges for insurance that consumers didn't even need.

A spokesperson for National General didn't respond to a request for comment.

Under The Microscope

In recent days, Wells has increasingly taken heat for aggressive sales tactics linked to a separate scandal involving millions of fraudulent accounts that were opened for customers without authorization. The Wells spokeswoman said the auto insurance situation is entirely separate and attributed it solely to a breakdown in internal controls.

But lawmakers in the U.S. Senate said the auto insurance scandal appears "eerily similar" to the fake account scheme that was revealed last year. In a letter to the bank's CEO and chairman, a group of senators—including Democrat Elizabeth Warren—demanded answers to a series of questions about why the insurance situation played out for so many years.

"The practices uncovered by this report raise myriad questions about Wells Fargo's business practices, risk management structure, and willingness to hold responsible parties accountable," the letter said.

Whether it was outright, purposeful negligence that's customary to Wall Street, or simply a failure of the bank's day-to-day procedures, Wells now finds itself in the crosshairs of regulators and consumers who've filed a litany of lawsuits in recent weeks.

New York state regulators issued subpoenas to the company early last month. (The spokeswoman declined to comment on the subpoenas.) Days later, a separate issue emerged, when the company admitted it had failed to refund guaranteed auto protection, or GAP, insurance money to people who paid their car loans off early.

Complaints filed to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau show that Thomas isn't alone with issues over Wells purchasing insurance and placing it on consumer loans.

In one complaint filed with the bureau in September 2016, an unnamed customer from Florida said he was hit with a significant additional auto insurance policy on his Toyota Prius that he hadn't authorized.

"Earlier this year they tagged my auto loan with an extra {$2,000.00} additional car insurance even though we fax the policy to them numerous times," the complaint said. "They declined to respond until I reached out to CFPB."

Lingering Damage

Kaylani Ross and Dee Lenz didn't have as much luck. In May 2014, the pair purchased a 2009 GMG Envoy with a loan from Wells Fargo. At the time, according to a lawsuit filed last month, Ross and Lenz obtained auto insurance from Geico. When the policy ended, Wells placed a collateral protection insurance policy on their account.

Later, the pair obtained auto insurance on their own and told Wells to stop billing them for the lender-placed policy. According to the complaint, Wells never did.

Ultimately, the Envoy was repossessed. The bank's internal report found that some customers had their vehicles repossessed multiple times, according to the Times.

"The victims of this scandal not only lost their cars, in some instances, but they were also left with damaged credit that is still not repaired," said Kellie Lerner, partner at Robins Kaplan LLP and counsel for Ross and Lenz.

"Wells Fargo is clearly under the microscope now after it has disclosed one scandal after another in recent months."

Know anything about Wells Fargo or the bank's auto insurance dealings? Send an email to ryan.felton@jalopnik.com, use our SecureDrop system, or find my contact for Signal here.