When is a submarine a car? This isn’t a riddle, it’s an honest question. I think if something has wheels and drives on the ground, it qualifies as a car. If that ground happens to be under a lot of water because it’s the bottom of the ocean, I’m not so sure that really changes things. It’s still a car. Just an underwater car. And, incredibly, these appear to have existed since 1894! Let’s dive in.

The story of wheeled, underwater vehicles is pretty limited; I think there’s some deep-sea submersibles that employed some wheels or rollers, and there’s some uncrewed underwater robots that use them, but there’s really hardly any actual wheeled underwater automobiles, as in wheel-propelled vehicles that drive on the ocean (or lake or river or sound or whatever) floor. But an inventor named Simon Lake actually managed to build a number of such vehicles, starting in 1894.

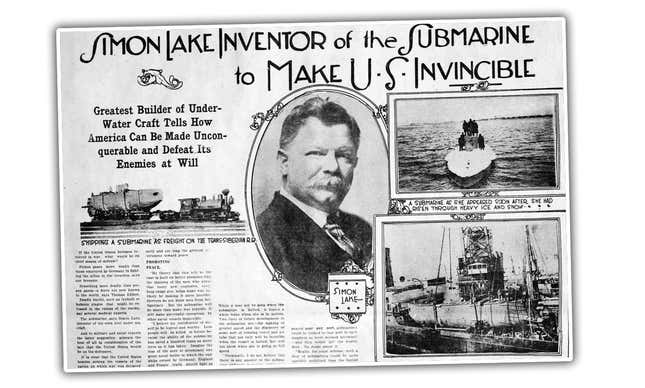

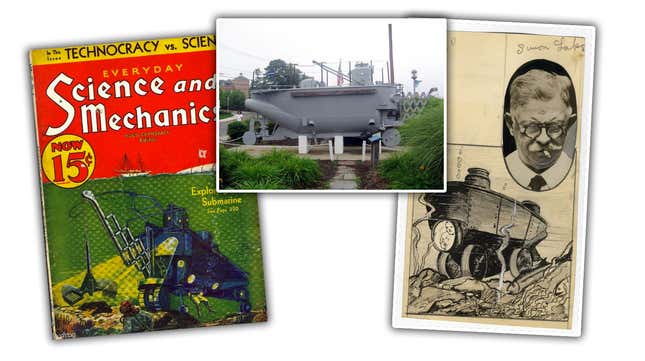

Simon Lake is considered by some to be the father of the submarine, though that’s pretty contested, as submarines seem to have many parents, including names like Drebbel, Bushnell, Fulton, and Holland. But Lake was absolutely a crucial pioneer, and his wheeled designs remain a fascinating and strange early development.

Lake wasn’t a great student, he didn’t really have any money, but he somehow still managed to build one of the first actually successful submarines, a dream that started by his reading Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.

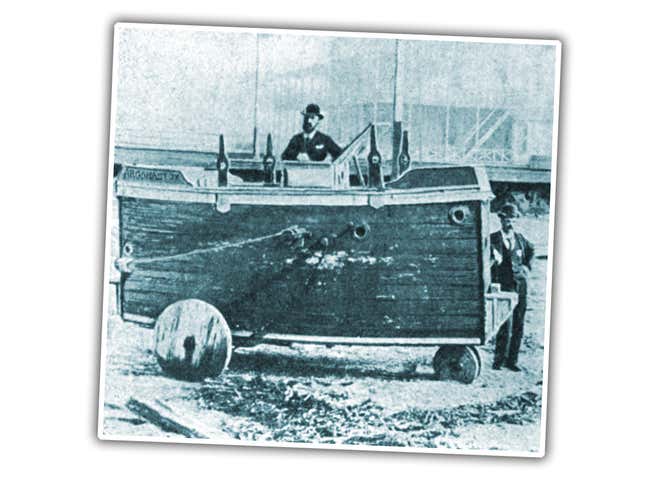

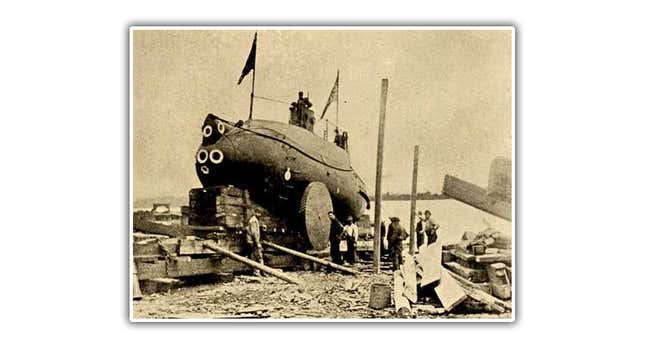

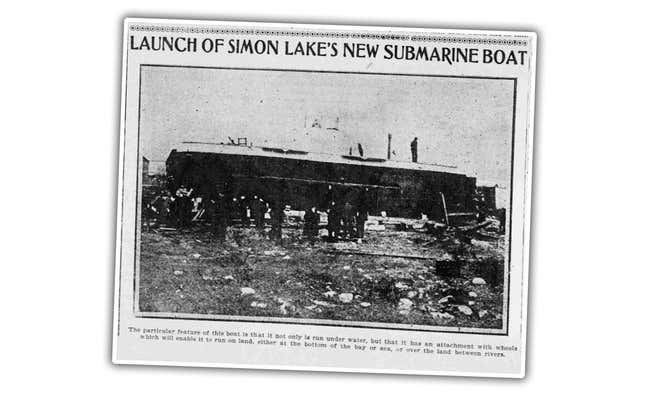

Unable to get funding from the U.S. Navy, Lake borrowed money from his aunt and built his first sub, the Argonaut Junior, on the cheap. And, unsurprisingly, it ended up being something that looked like some dude borrowed money from his aunt to build.

Here, look at this thing:

Majestic, isn’t she? All the grace of a backyard shed, mounted on discarded cable spools.

The Argonaut Junior was made from a sandwich of yellow pine planks enclosing tarred canvas to make a water-tight hull, air tanks pressurized to 100 PSI made from old soda fountain tanks, and, incredibly, was equipped with a diving suit made from painted canvas, with window sash weights for ballast, and a helmet made from a bucket—a freaking bucket—with a ship’s porthole mounted in front to act as a faceplate.

The craft was propelled by its wheels when on the underwater ground, powered by a big, human-cranked crankshaft. So this first one wasn’t motorized, as such, which may make it not really qualify as an automobile.

It did have an early version of an airlock, which allowed the diver to exit and enter the craft while it was underwater, which is pretty amazing.

Also amazing are these people that built a working replica of the Argonaut Junior; there’s a lot of great information in this video:

That’s a hell of an achievement for an after-work DIY project, and it’s really, really gutsy for them to take the thing actually underwater!

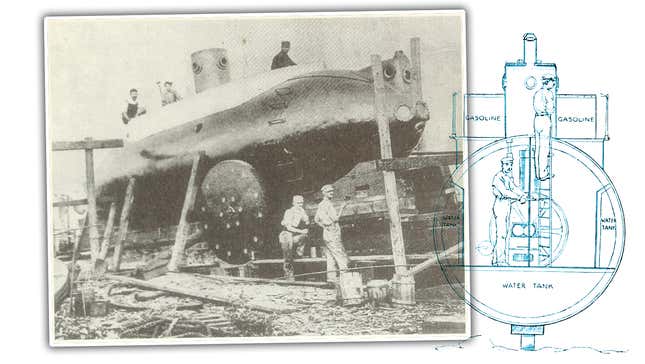

Incredibly, this crude wheeled submarine actually worked, and made several demonstrations, enough that Lake was able to get some investors to build a much more complex version of this same concept. These investors with Lake started the Lake Submarine Company in 1895, and began work on the Argonaut 1.

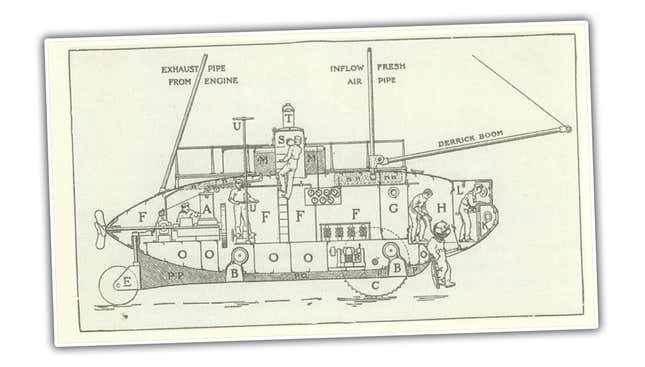

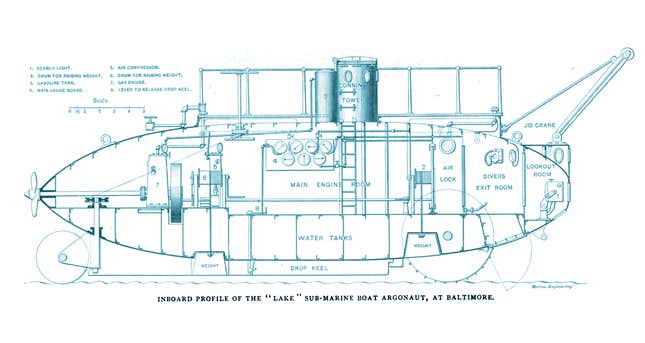

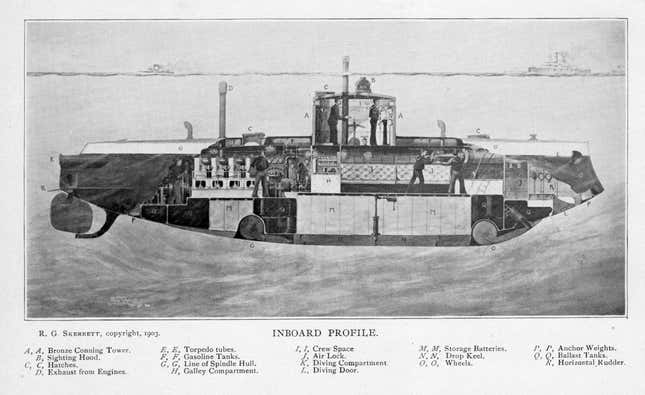

The Argonaut 1 absolutely meets the criteria of an underwater automobile, as this time the wheels were powered by an engine, a 50 horsepower gasoline motor that drove the propeller when the vehicle was in the water, the wheels when it was on the ocean/lake ground, and a dynamo to power the 16 incandescent light bulbs used to illuminate the interior and some searchlights, air compressors, along with an internal telephone system.

This was really cutting-edge stuff back in 1897. It’d be kind of impressive even today!

The result really was a sort of underwater RV, complete with a diver’s airlock and an external crane. It would move through the water, submerge, and drive around on the ocean floor. It doesn’t appear to have used storage batteries, relying instead on some hoses with floats that allowed air to be pumped down for use for people’s lungs and the engine’s carburetor, and another hose to release the exhaust gases.

That means that while the maximum depth would be limited by the length of these air supply/exhaust release hoses, the length of time the Argonaut I could remain underwater would only be limited by the supply of fuel, or maybe how long the crew could stand being down there.

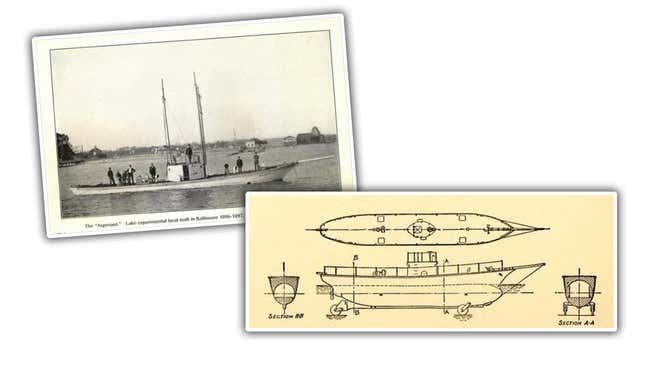

The Argonaut 1 made a successful crossing from Norfolk, Virginia to Sandy Hook, Connecticut — a distance of about 500 miles — making her the first submarine to successfully navigate open seas. That’s a big deal!

Another journey in 1898 took Lake and four crew on a 2000 mile journey around the Atlantic coast, sometimes on the surface and sometimes “driving” on the ocean floor. They were even able to retrieve fish and clams and oysters via their diver and airlock, which I suppose they may have eaten?

After this journey, Lake even got a congratulatory telegram from Jules Verne, which must have been the 1898 equivalent of getting a re-tweet from your celebrity idol.

In late 1898, the Argonaut I was taken into dock for an extensive re-fit, and would emerge in 1900 as the Argonaut II, bigger, better, more powerful, and capable of making a 3000 mile voyage, non-stop.

The re-fitted version looked much more conventionally boat-like, but retained the three wheeled setup of the earlier Argonauts.

Eventually, due to competition from submarine pioneers like John Holland, who was building subs for the Navy, Lake did build a military focused sub called the Protector, but Lake kept to his underwater-automobile plans, as this one had wheels, too:

In fact, it took the wheel concept a step further, employing retractable wheels, to allow for more efficient and speedy water-borne travel. You can see them labeled as O in this diagram:

Lake continued with the idea of wheeled submarines all the way to the end, with his last submarine, the Explorer of 1936, which was designed for research, salvage, and exploration missions.

I know these aren’t normally considered automobiles, but, as motorized, wheeled machines designed to drive on a surface, I think they qualify. I also think Simon Lake deserves a fascinating, if lonely, place in automotive history as the only manufacturer of underwater wheel-driven automobiles.