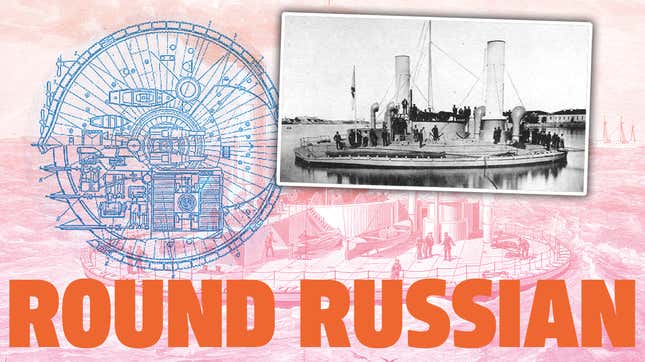

I know that, generally, war machines aren’t exactly endearing-looking things. Maybe that’s why I find this very strange circular old Russian warship from the 1870s so compelling. I mean, look at it. It’s like a floating Frisbee full of naval equipment. It’s kind of the least-threatening-looking warship that I’ve ever seen. History hasn’t been too kind to this ship, called the Novgorod, but I think it’s pretty fascinating, and I’m the captain of this blog, so now you’re going to hear about it, too.

The Novgorod is, fundamentally, an ironclad monitor. This is a type of steamship first introduced by the Union navy during the American Civil War, with the launching of the USS Monitor in 1862.

The Monitor was a revolution in naval design (way better than those garbage casemate ironclads the Confederacy was shitting out), a solely steam-driven, nearly completely iron ship with a powered, revolving turret. Most of the ship was under the waterline, and, it’s worth noting, was the first ship to have real flush toilets.

The Monitor was really the start of all modern warships, and as such the basic design was copied all over the world, including in Russia, which built copies of the Monitor’s follow-up ships, the Union’s Passaic class, as Uragan-class monitors.

Monitors were generally pretty low-draught ships, which made them especially well-suited to river patrol use, and their low freeboard made them generally not the best choice for ocean-going work. It so happened that in the late 1860s Russia, for a variety of reasons probably too involved to really go into here, was pretty worried about defending its rivers, so it wanted heavily-armed-and-armored ships to defend them.

Of course, all those cannons and iron armor meant more weight, which, in conventional ship design, tends to mean a deeper draught, which means they’re no longer usable in shallow rivers.

But that’s only if you’re thinking all boring and conventionally! If you open your naval-architecture mind, man, like Scottish shipbuilder John Elder did, then you’d realize that if you increase the beam of a ship (the width, basically) you could carry more of everything without increasing draught.

Imperial Russian Navy Rear-Admiral Andrei Alexandrovich Popov took these ideas and really ran, with the concept of widening the beam of a ship so much that the shape actually became a circle.

After testing the concept with models and a small (24-foot diameter) ship, a full-sized ship was approved, and construction on the Novgorod started in late 1871, with the ship having a diameter of over 100 feet, displacing 2,531 tons and having a draft of only 13 and a half feet.

With its low (only 18 inches to the waterline) freeboard, iron-armored hull, and central rotating turret housing a pair of 11-inch rifled guns, the Novgorod was very much in keeping with the traditional concept of a monitor, but the circular plan made the thing seem, well, bonkers.

To move this colossal frying pan in the water, six steam engines making a total of 3,360 horsepower were mounted at the stern, with each 560-HP engine driving its own solitary propeller. The engines and associated boilers were so massive that they took up about half of the internal volume of the ship.

As a result of so much interior volume being taken up by machinery, Novgorod did have more superstructures than a traditional monitor, with a large structure on the bow to house the crew, along with the pilothouse, funnels for the steam exhaust, and air intakes for below decks.

As anyone who has played with toy boats and maybe a plate or a frisbee in the water knows, moving something circular over the water isn’t particularly efficient, and all those steam horses were only able to push the Novgorod at 6.5 knots (about 7.5 mph) at full steam.

Then there’s the issue of steering. Even with tiny, almost vestigial hints of a bow and stern, the ship was still unrepentantly circular, and as such was not very directional at all. The rudder proved to be too small to be effective, with the hull shape blocking so much water that it took nearly 45 minutes to turn around.

What did work better was treating the ship as a sort of massive aquatic tank: since each engine controlled an individual propeller, the engines could be used to turn the ship more effectively, and one report at least seems to suggest it was very effective:

“The circular form is so extremely favourable to this kind of handiness that the Novgorod can easily be revolved on her centre at a speed which quickly makes one giddy. She can, nevertheless, be promptly brought to rest, and, if, needed have her rotary motion reversed.”

Of course, being able to spin like a record player isn’t necessarily the sort of thing really sought out in warships, and it was also widely reported that the ship would spin out of control from the recoil of one of its guns being fired, but this seems to be more of a myth based on conflating a lot of other reports of the era.

Even if it wasn’t pinwheeling around every time a gun was fired, the circular design still had plenty of flaws. The ships were not able to deal with rough weather, they rolled and pitched in all but the calmest sea, and on at least one trial cruise up the Dniepr river the current spun the ship (and its larger sister ship Vitse-admiral Popov) uncontrollably, presumably making everyone on board nice and dizzy.

Eventually, these circular ships did find a place as coastal-defense vessels, where they became, essentially, just heavily armored floating batteries. A more conventional ship design would have needed a lot more depth to hold that much armor, so, if you’re not such a stickler for your warships being, you know, all that mobile, they did find a niche where they made a bit of sense.

The legacy of these disc-shaped ships is pretty much a joke, but you have to admire the fact that these things exist at all. It’s not too often you get to see a bad idea realized at such a massive scale, and there’s something undeniably fun about that, at least for those of us unburdened by having to defend rivers from naval invasions.