With sheer cliff faces, hundred-foot drops, and a gradually decreasing percentage of oxygen in the air, the road that goes up to the tippy top of Pikes Peak is pretty frightening at the posted 25 mph speed limit. There are over 100 people who hit triple digit speeds on this road every year in the Pikes Peak International Hill Climb, some in an effort to break a class record, others seeking the kinds of thrills you’d expect in skydiving or free climbing.

(Full Disclosure: Acura brought me to Pikes Peak to watch two NSXs, an RDX, an MDX, and Peter Cunningham’s TLX race cars run up the mountain, as well as eat and stay free of charge.)

“I kind of forget which corner is which in the bottom part. They all look pretty similar,” comments Peter Cunningham on his third year return to the mountain. With so many corners, it’s almost impossible to memorize the whole thing. I’m told that most of the right hand corners are safe, it’s the lefties that will get ya, and all of the corners without a guardrail can be taken pretty much flat out. The single exception is the so-called Evo Corner.

The lack of oxygen at the top means drivers without a plumbed supply start to feel a little drunk from mild hypoxia.

From the start, there’s a lot stacked against a hill climb racer. Any number of things could potentially go wrong. At the limit on the peak, you’re a tire puncture away from the permanent shroud of death. Someone running before you could kick some dirt up onto the surface in your braking zone, a marmot could poke its head out of its hole at the wrong time, you could just plain forget where you are on the hill. And yet, every year, people come back to race in America’s second-oldest motorsport event (following the Indianapolis 500).

There was a death this year at Pikes Peak. A life filled with such promise and talent was cut short by this mountain, this endeavor for speed. While those of us at the base of the mountain, myself included, did not hear that a death had occurred until several hours later, we knew that the mountain had been shut down, and that the medivac helicopter had been dispatched. Those delays cast a shadow over the entire event. For every minute the schedule was pushed back, our minds were swarmed with the thought of the people involved in the incidents that had caused it.

There’s a feeling that Pikes Peak is the last of its kind, as though it’s the Wild West of the motorsport world. This kind of run-what-you-brung racing doesn’t really exist anywhere else. There is an eclectic mix of home-brew specials, track day monsters, and oddities you won’t find anywhere else. In spite of the danger, or perhaps in part because of it, this event attracts an interesting group of racers and engineers and builders.

Friday - Fan Fest

Fan Fest is the Friday before the Pikes Peak hillclimb race in Colorado Springs, the town near the mountain. It amounts to something resembling a mix of extreme sports festival, live music, and massive car show. Not everything on the street is racing on Sunday, but most of it is. This little Honda Beat (it belongs to @thehondahoarder on Instagram) wasn’t racing, but it did catch my eye, for obvious reasons.

This wild racer used to be a Porsche 914, but has evolved into a turbocharged GM LS7-powered wedge with exaggerated aero. This might be the single most radical departure from what the car used to be. I can really only tell it was 914 based because of the shape of the door and that tell-tale chrome door handle. Not much stock left here.

Fan Fest is pretty neat, but there were way too many people there, and the Colorado afternoon rains came, so I decided to head to a bar to weather the storm.

Saturday - Driving the hill and the Penrose Heritage Museum

In the bright and early Saturday morning sun, I loaded into a white Acura RDX A-spec an pointed the nose toward the sky.

Acura had entered five different cars in this year’s Hillclimb: an ex-World Challenge Acura TSX for pro-driver Peter Cunningham, an NSX for principal powertrain engineer James Robinson, another NSX for principal suspension engineer Nick Robinson (James’ brother), an MDX for senior steering performance engineer Jordan Guitar, and an RDX for steering test engineer Steven Olona. The latter four all work together at Honda R&D America, a skunkworks racing team putting road-based Acura products to the test in the harshest possible environment.

I was given the privilege of having James Robinson sit right seat for my drive up to the top. Even though we were going as slow as tourists up the mountain, following the posted speed limits, it was nice to hear some of the strategy involved in getting to the top. James said that some drivers will count corners in their head, but he prefers to take them as they come, rather than risk getting confused. He started racing at Pikes Peak several years ago in a Honda Fit, and has graduated to a slicks-and-wings Acura NSX.

I did get a short stint up the hill in the Acura NSX pace car, admittedly still at slow speeds, but Cunningham forgot to put fuel in the damn thing and the low-fuel light was on. Rather than risk running it out of fuel, we parked it and the team came back to get it with a can of fuel later.

Once up at the top, I popped into the summit house to grab a donut. These cakey donuts are a special recipe that only works at altitude. I’m not sure what it is about them, but even without frosting, glaze, or sprinkles, they’re just the right amount of sweet.

And for the record, I definitely got light-headed at 14,115 feet above sea level. Just walking for a few minutes was taxing without taking a hit of canned oxygen. Thankfully, most of the racers have an onboard system for this now.

Afterward, we all popped over to the Penrose Heritage Museum in Colorado Springs for a look at some of the historically significant runners. I won’t give away the whole thing, but it was totally worth a tour.

The above is Nobuhiro “Monster” Tajima’s old racer. Before the XL7 and the Escudo, he raced a Suzuki Cultus compact with an engine powering each end of the car. The driver’s seat is smack in the middle. This car broke the PPIHC record in 1993, but was beat later that day by Paul Dallenbach’s open wheel racer.

Rhys Millen’s Hyundai PM580 prototype has been a favorite of mine from the start, as it brought sports car racing technology to hillclimb. This tube-frame racer has a carbon body, active aerodynamics, and all the fixin’s. Powered by a 4.1-liter version of the Genesis V6, and fitted with an HKS turbocharger, the car produced 750 horsepower. It was never quite enough to win, or break the 10-minute barrier, however, as minor issues cost Millen time in both years it ran, 2010, and 2011.

No display on the peak would be complete without at least mentioning the perils involved. Thankfully, both the driver and co-driver (co-drivers are no longer allowed) walked away from this shunt. This Evo is why Evo Corner is called Evo Corner.

And I thought this was a neat visual representation of the gradual march toward faster times. The red times represent years when a new record was set. I think Romain Dumas’ Volkswagen I.D. R record will stand for a few years to come.

Sunday - Race Day

To get up on the hill you have to wake up very early. Many people drive up the night before and camp out. As I was driving in, I saw more than a few people sleeping on inflatable mattresses in their truck beds. These are dedicated fans, inspired to make the trek to the mountain every year to get a glimpse of glory, to witness history being made.

The motorcycle segment of the race, which kicks off the day in the early morning, is bookended with incidents. The first bike of the day made it about half a mile up the hill before Mark Bartle and his Honda CRF450 went sliding off the road and bouncing around in the trees. Luckily Bartle came out without permanent injury. Rennie Scaysbrook set a new motorcycle record up the hill riding an Aprilia Tuono with a 9:44.963 time.

Then came the cars.

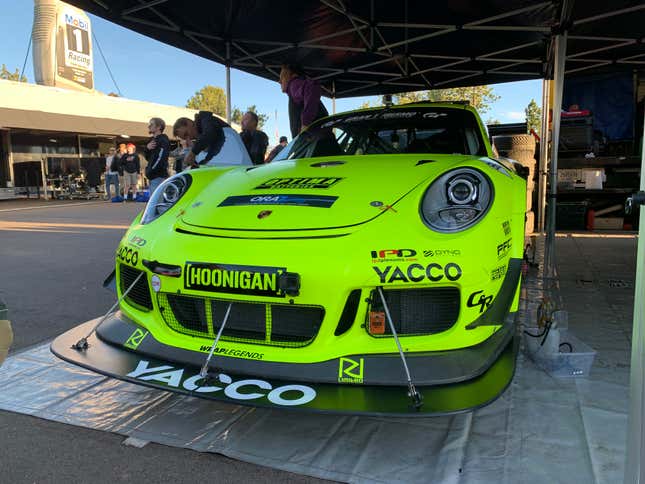

There was a single Honda-powered Wolf-chassis prototype running in the race with Robin Shute driving, which won the whole shooting match with a 9:12.476, which is a far cry from 2018’s winning time. Shute could take it easy and still win, as he ran 11 seconds faster than second place, this day-glo 911 built by BBi Autosport out of southern California.

Acura’s fastest car, the all-wheel drive 550-horsepower big-wing TLX GT with Peter Cunningham at the wheel, was third off the line at the start. Even though his sedan had more weight and less power than the second placed Porsche, he ran within one second of the bright green P-car. Cunningham ran several tenths faster than the Porsche in sectors 2, 3, and 4. You know where he lost time? That’s right, sector 1, where he mentioned having a hard time telling corners apart.

From the start line you can see the cars take off and disappear up the hill. Then you’re stuck watching sector times on a screen in the paddock to see how quickly they make it to the top. It’s a nerve wracking 10-ish minutes of waiting for four time measurements to come in that indicate the car made it to the top safely.

“Drive safe, make it to the top,” was the common refrain repeated to racers as they lined up to take on the hill. That’s life on the mountain.

The five Acuras finished as follows:

Peter Cunningham (Acura TLX GT) - 3rd Overall, 1st in the Pikes Peak Open class, new record - 9:24.433

James Robinson (Acura NSX) - 13th Overall, 4th in Time Attack 1 - 10:07.940

Nick Robinson (Acura NSX) - 17th Overall, 5th in Time Attack 1 - 10:25.556

Steven Olana (Acura RDX) - 64th Overall, 4th in Exhibition - 5:17.806 Weather Shortened Course

Jordan Guitar (Acura MDX) - 71st Overall, 5th in Exhibition - 5:33.372 Weather Shortened Course

James, running slick tires, massive aero, and big turbos on his race-prepped street NSX was aiming for a sub-10 minute time. Unfortunately, Dai Yoshihara’s Toyota got a re-run to come back down and start again. That meant the NSX engine bay heat soaked, and the pre-heated tires cooled off as they sat at the start line waiting for the run to start.

That’s how it is sometimes, better luck next year. The hill doesn’t give a shit how well you’ve prepared.

This car gets my honorable mention as one of the coolest hillclimb racers. Layne Schranz runs this ex-stock car circle-track racer at Pikes Peak, and this year it came home in 5th with a 9:40.630 time. Under the hood is a twin-turbocharged V8. Check this shit out!

Yeah, that’s an impressive engine bay.

I thought this BMW 2002 was worthy of note because I also saw it parked on the salt at Bonneville for Speed Week last August.

And I’ll leave you with a smattering of the cars I saw in the paddock. The level of racing ranges from insane factory-built and entered prototypes down to just a guy running an old Mustang, or taking their track car E36 BMW to try to set a decent time. For some competitors it’s all about setting a record, for others, it’s just about proving you can.

I’ve been dreaming about attending Pikes Peak for years, and was ecstatic to finally get the opportunity to walk these hallowed motorsports grounds. It was one of the few remaining bucket list events to attend, and I’m so glad I got the opportunity. That said, from a spectator perspective, the race is a bit lackluster. If you want to get a good view point, you have to drive up the mountain at 4:30 AM and you’re stuck there until the whole thing is over. This year people were stuck until about 6:30 PM. And you only get one perspective. Wherever you are on the hill, you’re there all day. If you have the fortitude for that, go for it. I’m not sure I do.

While PPIHC is a bit underwhelming for a spectator, it seems to be the only thing in the world that provides this kind of adrenaline rush for a driver or rider. I think I’ll be back at Pikes Peak eventually, but perhaps as a driver rather than a looky-loo.

Run an old race car, run a time-attack Nissan Leaf, run an Acura RDX with side-exit exhaust, it doesn’t matter what you run, really. Just run.