Why Cars Intentionally Ramming Into Crowds Is A Relatively New Problem

It's happened again. In Toronto, a suspect used a Ryder van to drive into a crowd, this time killing 10 people and injuring 15 others just trying to get through their Monday routine. It is yet another example of cars—one of the most high-profile symbols of independence and Western wealth—being used as weapons against civilian populations with increasing regularity, and not as bombs or deliveries for explosives, but on their own.

This is a relatively recent phenomenon, and it's also a byproduct of the other ways that we've cracked down on terrorism in the years since the Sept. 11 attacks. Of course, problems—including violent ones—involving cars are well-known and well-documented. Cars have been around for more than a century now and things like traffic, theft, and drunk driving crashes have been around for only slightly less time.

At first, cars were mainly used to deliver bombs. The first car bomb was probably in 1905, when men connected to an Armenian separatist movement attempted to blow up Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II's car. In 1914, Serbian separatists first attempted to throw bombs under Franz Ferdinand's open car, before shooting him in the same car and kicking off World War I. In 1927, a truck full of dynamite was involved in one of the series of explosions that killed 38 elementary school children and six adults in Bath, Michigan in what remains the largest school massacre in American history.

Many of the worst bombings all over the world have involved cars. Cars and trucks were used in some of the worst attacks perpetrated by the Irish Republican Army during the "Troubles" between Protestants and Catholics in Ireland from the 1970s to the late 1990s. In 1981, a car laden with explosives rammed into the Iraqi embassy in Beirut, killing 61 people. It was the American embassy in Beirut's turn in 1983, when a suicide bomber detonated a car bomb, killing 63. Cars as delivery devices for explosives continued into this century, with the 2000 bombing on the USS Cole and 2007 bombing of Scotland's Glasgow airport.

There are hundreds more examples throughout the world. Today, car bombings regularly rock cities in tumultuous countries like Iraq, Afghanistan and Somalia, but the use of a car itself as the primary means of destruction is relatively recent.

This is, in essence, a whole new form of terrorism.

Terror begins by perverting what was once normal. Tech-savy terrorists began to spread the word about the ease of using cars to attack crowds through their sophisticated network of online publications and social media profiles. In the fall 2010 issue of Inspire, an online al-Qaeda publication, an article entitled "The ultimate mowing machine" gave its readers a blow-by-blow on how to most effectively attack crowds using cars themselves. The publication called on its fans to create havoc by randomly attacking crowds with cars around the world, CNN reported.

Before 2006, ramming attacks were sporadic and largely focused on government, military, and police instillations without much effect in terms of damage. Then an attacker named Mohammed Taheri-azar drove his SUV into a crowd of students at the University of North Carolina. Nine people were injured in the attack, which CNN reported Taheri said was in retribution for Muslim deaths overseas. In 2008, a Palestinian man killed three people by driving a large construction vehicle into a crowd in Israel.

After 2010, ramming attacks spiked, going from a few attacks around the world each year to five attacks in 2011, seven in 2012 and 2013 and spiking to a staggering 25 in 2014, according to the Global Terrorism Database. The death tolls have also risen as terrorists hone the car as a weapon.

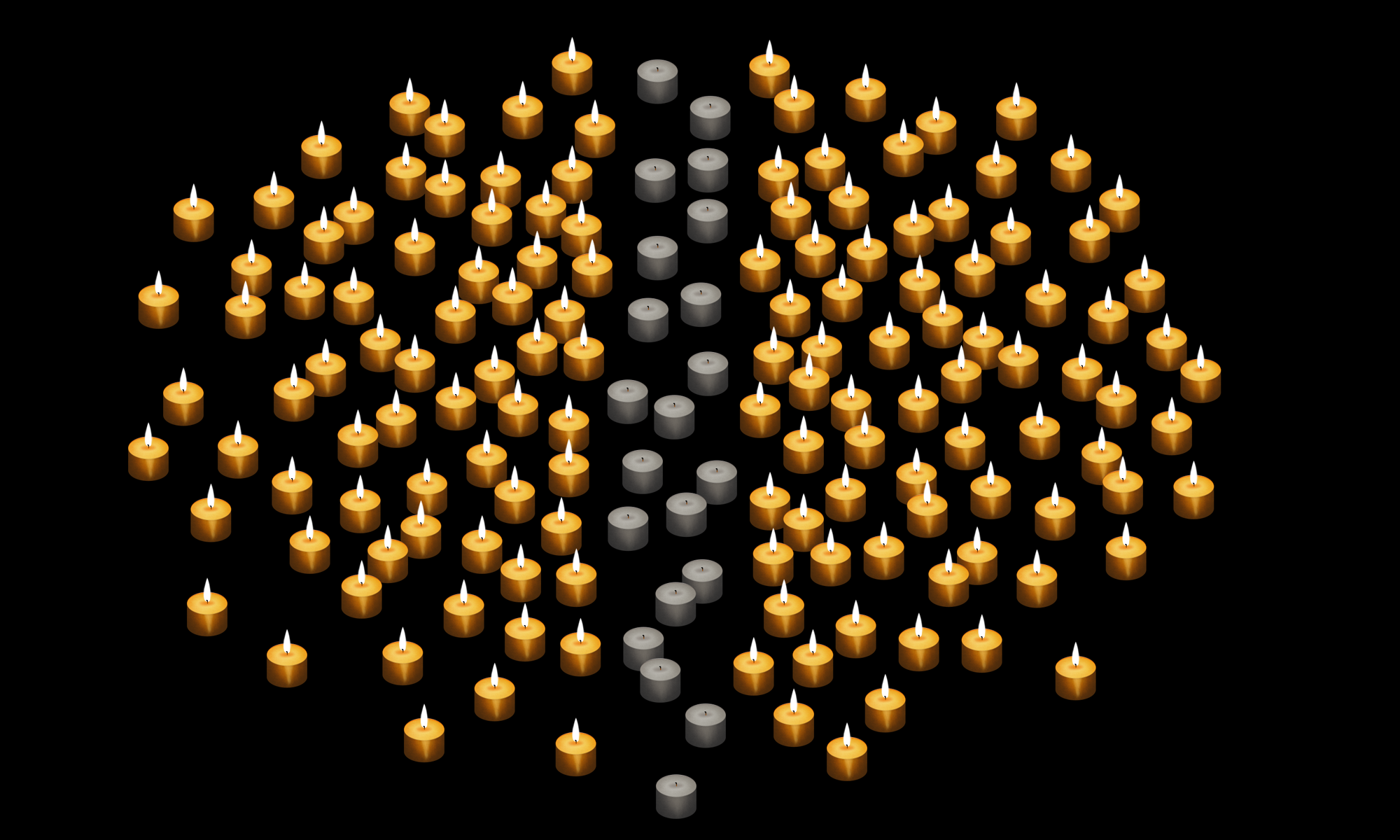

From 1970 to 2010, 87 people died in such incidents. But in 2017 alone, 32 people died in ramming attacks, according to the Counter Extremism Project. In the last eight years, 328 people have died this way.

And it's little wonder why. Ramming is the everyman attack. It requires no technical knowledge, no intricate plans. Just get any vehicle, the bigger the better, and drive it into a crowd. Inspire praised ramming as "...a simple idea and there is not much involved in its preparation." ISIS also praised the tactic as a way for a jihadist to do their duty in its Rumiyah magazine in 2016.

A few have answered those calls with tragic results. On July 14, 2016, 84 people died when a truck drove into a crowd at a Bastille Day celebration in Nice, France. From there, the car as an open-sourced terrorist weapon began to gain momentum. Twelve were killed just a few months later in a terrorist attack on a Christmas market in Berlin.

Of course, the car as weapon is not limited to one ideology. The car attack on a crowd during a protest in Charlottesville, Virginia shared many elements with attacks abroad. Murder suspect and alleged Nazi sympathizer and white supremacist James Alex Fields wasn't a professional, day-to-day terrorist—just someone who took the calls to violence of his extreme ideology to heart.

Fields was charged with with second-degree murder, malicious wounding and failure to stop in the ramming that resulted in one death and 19 injuries.

Just a few days later on Aug. 17, 13 people were killed and more than 130 were wounded in Barcelona, Spain, after a man drove a van into a famous pedestrian space, the Guardian reports. ISIS took responsibility for that attack.

So why the rise in recent years? Mary Beth Altier, a clinical assistant professor at at New York University's Center for Global Affairs, said this is an unfortunate side effect of how countries across the globe have cracked down on terrorism and, in some cases, weapon access in recent years.

"Our counterterrorism polices have evolved," Altier said. "So now it's much more difficult to hijack a jetliner, for instance, because our security services have adapted. As a result, terrorists have adapted."

She also said it's a symptom of the loose nature of terrorist groups, particularly those motivated by ideology looking to spark similar actions by those who identify with their aims.

"The second reason is groups like ISIS are much less centralized and are relying on a strategy of leaderless resistance," she said. "They are calling on anyone, anywhere to attack. Since such attackers aren't regular members of the group they usually lack the skills or training to say, build a bomb. But anyone can drive a car. The reliance on cars is, in part, a result of the decentralization of terrorism and a dependence on unskilled attackers."

Last May, NBC found that 173 people had been killed in ramming attacks in the last three years, a number that's clearly risen since. More than any body count, however, the psychological aspect of the attacks that provide the most effect. Public spaces, known as "soft targets," are meant for ease of use and large gatherings. These attacks can put any celebration or public event at risk.

Cars are everywhere, and even if you're not a particularly good driver, you can still do a lot of damage. (In fact, that's kind of the point.) Rammings also show the resilience of terrorist attacks. They spiked in Israel in the early 2000s after Israel put up a wall trying to block out Palestinian attacks. It's not that the ramming attacks were a response to the wall itself, so much as a shift in tactics as it was harder to get through with weapons.

But as with other methods of terrorism, cities and law enforcement officials are now trying to physically mitigate and prevent ramming attacks—at least to the extent that they can be prevented.

Security services in Northern Ireland have been protecting crowds for decades by routinely establishing perimeters around where crowds will be and using firetrucks to direct and protect the flow of foot traffic. We should also expect to see more bollards and security barricades popping up in public places. New York City is installing "blockers" along the West Side Highway bike path after a suspect in a rented Home Depot truck rammed a crowd last year and killed eight people, Gothamist reported.

Any place that experiences large crowds is currently looking to install more of these squat little concrete barriers designed to stop cars in their tracks. Las Vegas installed 700 on the Strip, a decision the city called "life and death," according to the Washington Post.

But even if cities take every conceivable step, it will not be enough to protect normal people entirely from such attacks. Such barriers merely shift terror to other soft targets, places not prepared for such attacks. And we can't live in total lock down forever.

Considering such attacks have happened in nearly every corner of the world and were driven by a wide variety of motivations, from Uyghurs separatists in China to white supremacists mad about Black Lives Matter protests to a man angry that women wouldn't have sex with him, it seems unlikely that we will be able to stomp out this form of terrorism any time soon.

But a story from one of the longest-running conflicts in Europe may point to an answer. In 1996, a meeting was held between Irish and British security officials to discuss if the Irish Republican Army's ceasefire could be considered a genuine step towards dissembling the IRA's arsenal. Journalist Tim Pat Coogan reported a Royal Ulster Constabulary officer said grabbing the IRA's weapons didn't matter as much as his fellow Ulstermen thought.

"Two men with shovels can make up a thousand pound bomb in a Fermanagh cowshed and, if for some reason the operation has to be aborted, they can decommission it again, all within 12 hours," the unnamed officer said. "You can't decommission shovels. It's minds which have to be decommissioned."

While terrorism has actually declined along with other forms of violent crime since the 1970s, according to The Atlantic, it's the resilience, the sheer randomness that still makes this form of terrorism especially scary—and hard to prevent. And the world's leaders also seem to be running out of ideas on how to stamp down on terror.

It might seem easy to point to autonomous cars as the answer for this problem. Take driving out of human hands entirely, and you potentially remove cars as a weapon. But there's little reason to think that driverless cars will be any less available to terrorists than ones with a person in the driver's seat. They may grown only more deadly.

Ultimately, it's these ramming attacks that serve as a reminder that the only way to truly prevent terrorism is to address its underlying causes. We can never truly be safe from terrorism until the issues that spur people to commit these acts—which can be as complex as thousands of years of global history and as personal as a hatred of women—are finally addressed.