This Day In History: Ford Makes Standard The 40-Hour Work Week

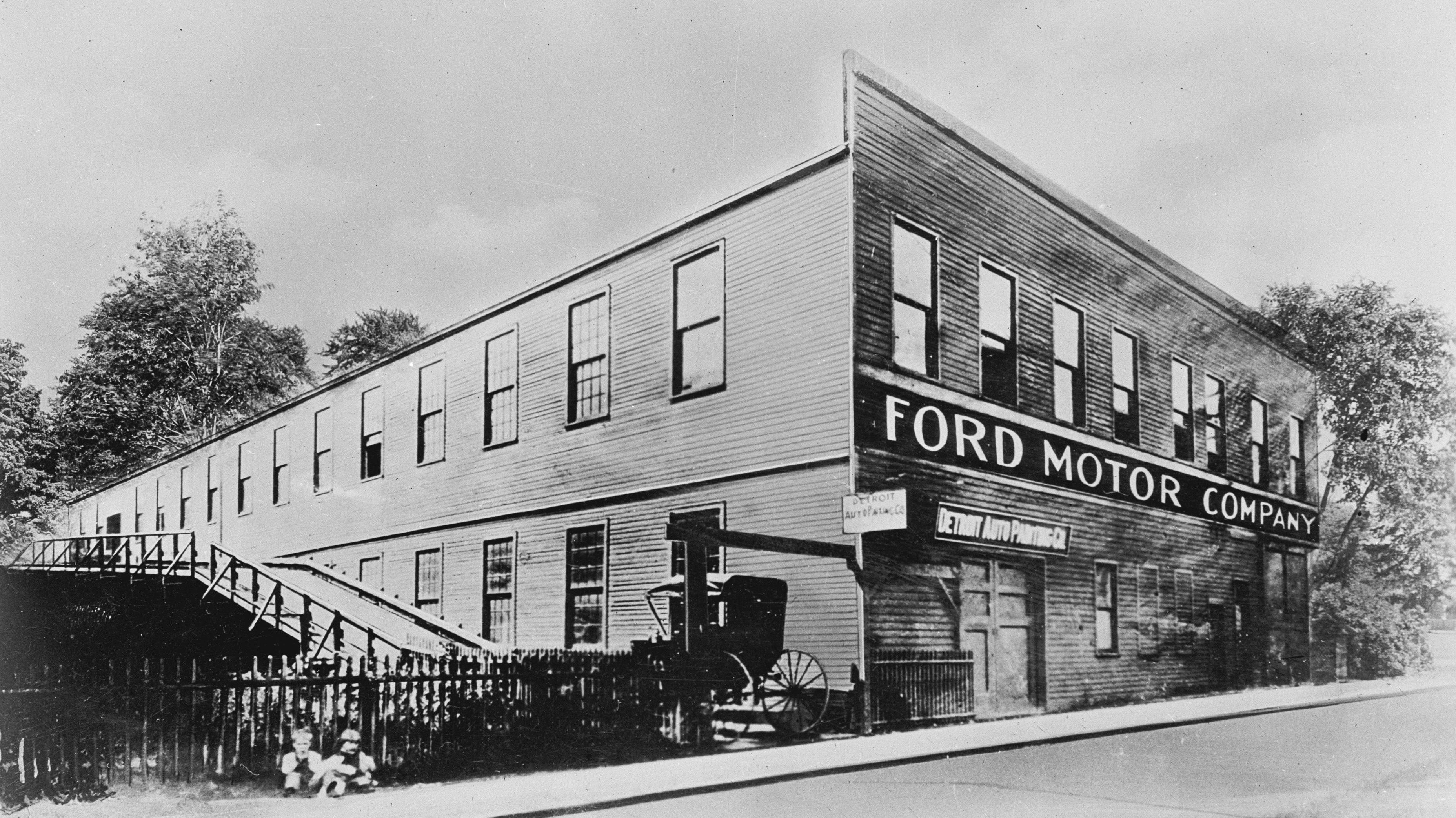

What we consider to be the traditional work week today—a five-day schedule where we clock 40 hours—wasn't always the norm. And we can thank the Ford company for cutting our work week down from six to five days when it instituted the policy on May 1, 1926.

(Welcome to Today in History, the series where we dive into important historical events that have had a significant impact on the automotive or racing world. If you have something you'd like to see that falls on an upcoming weekend, let me know at eblackstock [at] jalopnik [dot] com.)

Now, Ford wasn't the first company to adopt the five-day, 40-hour work week, but it was the most influential, and it provided a functional example for the United States government that allowed it to mandate a cap on working hours. It set an example that married together two very distinct notions: that workers need more than one single day to rest and recover, and that workers would be far more productive if they were required to get the same amount of work done in a smaller amount of time. So, for as much as you might want to think the Fords were reducing the work week out of the kindness of their own hearts, they were mostly trying to get the most bang for their buck.

Here's a little more on the strategy behind the move, from Hagerty:

In 1914, he succumbed to the pressure of widespread unemployment and labor unrest by announcing that Ford Motor Company would pay its male workers a minimum of $5 per eight-hour day, more than twice the $2.34 per nine-hour day they had previously been paid. Female workers were equally compensated beginning in 1916. While the wage increase reverberated throughout the auto industry, the move boosted productivity, loyalty, and pride among Ford's workers.

The 40-hour work week had the same effect. Three months after the announcement, the Detroit automaker extended the policy to office personnel.

I mean, think about it: if you weren't required to bust your ass as many days as your fellow workers and you were getting paid a hell of a lot more, you'd probably feel pretty rewarded, too. Yes, you'd likely benefit from that extra day of rest and relaxation, but you'd also be providing the company you work for with the benefit of your harder work when you were on the job.

I think the best way to temper the benefits of the 40-hour week is to remember that Henry Ford was not exactly the most charitable person; his main goal in life was to create a more efficient manufacturing process for his automobiles, which meant doing it faster, better, and cheaper than his competition. The development of the assembly line process and the interchangeability of parts on the Model T were massive developments in the auto industry that resonated with manufacturing industries everywhere—but the whole purpose was to get more people buying Fords, which would line the Ford pockets with much more money. If Henry Ford was really in it for the benefit of his workers, he wouldn't have been so vehemently anti-union.

The thought process behind the 40-hour week was that it provided employees with "eight hours for rest, eight hours for work, eight hours for what we will," plus two full days off to spend with family. And eight hours is about the cap for how successfully we can work, the CDC reports. You're less alert and more likely to suffer long-term illness if you continue working after eight hours. That contributes to exhaustion, burnout, and all those other nasty things that prevent you from actually competently doing your job.

Of course, modern society has thrown in some monkey wrenches, including long commutes, telework, unlivable wages, and more. It might be time for the Ford of our generation to come up with a different plan to prioritize both productivity and worker health.