How Lucy O'Reilly Schell Used Motorsport To Fight Fascism

Schell, a racer herself, spent her fortune to fund a car for Jewish driver René Dreyfus.

If Lucy O'Reilly Schell's name sounds familiar, that's likely because you've recently read Faster: How a Jewish Driver, an American Heiress, and a Legendary Car Beat Hitler's Best by Neal Bascomb, which tells the story of how she funded a Grand Prix team for Jewish René Dreyfus in the hopes of beating the dominant German teams of Adolf Hitler's Nazi regime. But that's only one part of the story of a woman who was an exceptional racer in her own right.

Welcome to Women in Motorsport Monday, where we share the stories of the badass women who have conquered the racing scene throughout the years.

O'Reilly Schell was born in Paris, France on October 26, 1896 and entered life in a deeply international family. Her grandparents had emigrated from Ireland to the United States during the Great Famine, and her father married a French woman in Brunoy, France, where he fell in love. Nine months later came daughter Lucy, and soon after, the family moved back to America.

But her father, Francis Patrick O'Reilly, had become a wealthy man. Between a construction business and some strategic land investment in Pennsylvania, O'Reilly had established himself an impressive fortune — one that his daughter would later use to great effect.

As with most moneyed young adults, O'Reilly Schell headed off to Europe for her personal Grand Tour, which was something of a rite of passage for anyone seeking a worldly education. You tour the Old Country, see the sights, admire the art, listen to the music, and indulge in the cuisine of Europe. And then you return home an unmistakable member of high society, something that was especially rare for a woman in America.

But Lucy O'Reilly didn't do that. When World War I cut her trip short, she would have been forgiven for returning home. Instead, she moved to Paris and volunteered in a military hospital. And somewhere in there, she met Laury Schell.

Schell, the son of an American diplomat, had spent most of his life in Europe. He was born in Geneva, Switzerland and grew up in France, and he'd developed a penchant for fast cars and the kind of cross-country racing that primarily existed in Europe at the time. The two married and had children, and Lucy was hooked. Before long, she wasn't just watching the races — she was competing in them, too.

Her first major race came in 1927 at the Grand Prix de la Baule, where she drove a stunning Bugatti T37A to a 12th place finish. Records show that, of 17 entries, only 14 finished (and that perhaps another woman was competing in the race as well: Charlotte Versigny). And yes, that made her the first American woman to compete in Grand Prix racing.

The following year, she competed in more events with that same Bugatti. At the Grand Prix de la Baule, she finished eighth of 16 entries and 14 finishers. At the Grand Prix de la Marne, she finished sixth. She took her first win at the Coupe de Bourgogne voiturette race that same year.

In 1929, O'Reilly Schell turned her eye to the rally scene, which presented the unique challenge of contesting difficult terrains and multi-day adventures. That year, she took an impressive eighth of 27 finishers at the notoriously difficult Monte Carlo Rally, where she was the only woman to compete. She took victory in a Coupe de Dames race designed specifically for women. And she kept at it for several years.

And then she found Delahaye.

At that time, Delahaye was known for making trucks, not sleek race cars, but in 1933, majority shareholder and widow to one of Delahaye's original founders, Madame Desmarais, decided that she wanted to have a racing team. She told the company's manager of operations, Charles Weiffenbach, that he would set up a racing department. With the help of an engineer named Jean François, Weiffenbach did just that, and Delayhaye had two racing vehicles ready for display at the Paris Salon de l'Automobile that year.

O'Reilly Schell saw those cars. She and her husband went straight to the Delahaye offices, and O'Reilly Schell laid out her plans for a special car designed to her personal specifications. She wanted the shorter wheelbase chassis, but she wanted it outfitted with the more powerful engine of the longer wheelbase chassis. This wasn't a car for racing, though, at least not right away. She just wanted something beautiful to drive.

Here's where she did something that was, frankly, genius. When her order was put on hold — after all, she was asking for a particular one-off model while the company was still setting up its racing department and developing something other than a heavy-duty truck — she decided to speed them along by encouraging her friends to order the exact same hybrid model she had requested. That way, they couldn't keep putting her on hold.

Schell rewarded Delahaye by selecting them as her automaker of choice when, in 1936, she inherited her father's fortune and decided to found her own racing team, named Écurie Bleue. And because Delahaye had decided that running a works team of its own was too much work, O'Reilly Schell essentially became the owner of a works Grand Prix team. The first American woman to do so, I might add.

Her goal? To go Grand Prix racing and beat the Germans. O'Reilly Schell knew she was skilled, but she also knew that she'd need someone with a lot more experience to take on the ultra-fast cars that were coming out of Nazi Germany, where racing wasn't just a sport but was a symbol of national pride. After the mortifying defeat of World War I, Adolf Hitler used his country's technical prowess to raise the morale of Germany, which meant he was pouring an absolutely ridiculous amount of money into any automaker that could find success. Dominating on the international Grand Prix circuit had become, in a way, a metaphor for dominating the world.

During that same time, the once-dominant French Grand Prix teams had fizzled out. The automobiles coming out of the country weren't inspired, and the racing results from French manufacturers showed it. Schell, who was keenly aware of the political situation of the era, decided that she'd fund her own French outfit and attempt to bring her adopted country back on the map.

And that's why she signed René Dreyfus. A Jewish driver (who, Neal Bascomb contends, wasn't necessarily a devout advocate of religion but instead was caught up on the wrong side of history more because of his name), Dreyfus had been blackballed by the Grand Prix circuit. Hiring a Jewish driver in Europe, which was being overrun with anti-Semitic sentiment, was risky, even though Dreyfus was a damn good driver. When O'Reilly Schell saw his career had stalled through no fault of his own, she scooped him up for her Écurie Bleue.

In 1937, though, it seemed that the French government had come to realize that it was falling behind the Germans and that the German success in racing was becoming massively political. It tried to fund a state-led effort to build a new Grand Prix car, which was a disaster. So, it took some money and set it aside, advertising a race called the Grand Prix du Million, or Le Million. The goal was to award one million Francs to the French manufacturer whose car was able to cover 124.3 miles at a speed exceeding 91 mph by the widest margin at the Montlhéry autodrome before September 1, 1937.

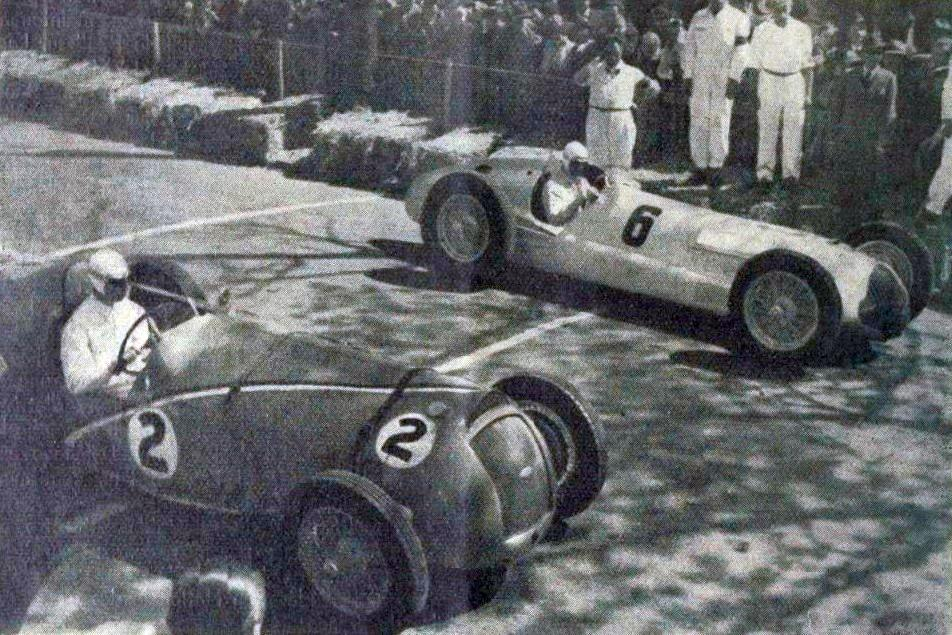

Only two marques really showed up to compete: Delahaye with Écurie Bleue and Bugatti. Écurie Bleue, with Dreyfus as a driver, just barely met the goal for Le Million in late August. Bugatti showed up to the track soon after to try to take victory. The reason it failed was due to mechanical breakdowns at the very last second.

O'Reilly Schell split the winnings between Delahaye and her team. Half of her team's winnings she gave to Dreyfus. With that motivation under their belt, O'Reilly Schell, Dreyfus, and Écurie Bleue looked to the 1938 Grand Prix season.

The year wasn't the rounding success that O'Reilly Schell would have hoped. Dreyfus took victory at the first race of the year at the challenging Pau circuit, but it was a non-Championship race, which meant it didn't count for overall points. The team also took victory at Cork, though the field was extremely small and didn't feature the Italian and German competition O'Reilly Schell was seeking to beat.

Things, though, began to go sour. The French government had announced yet another million Franc prize... and awarded it to Talbot.

O'Reilly Schell was distraught. She was counting on that money to develop a Delahaye single-seater, and she had very good reason to expect to win the prize on merit of Écurie Bleue's accomplishments that season. Heartbroken, she withdrew the team from the French Grand Prix. For the next race, in Switzerland, she swapped the Delahayes for a Maserati 8CTF.

But bad luck continued to follow. The Maseratis didn't live up to their hype, and in October 1939, the Schells were involved in a road accident. Laury was killed. Lucy was seriously injured. But to ease her pain, she renamed her team Écurie Lucy O'Reilly Schell and intended to contest another season of Grand Prix racing.

It wasn't meant to be. In 1940, it became clear that France was the next target on Hitler's list. Schell knew that Grand Prix racing would likely become nothing but a pipe dream, and she found a reason to leave the country and take Dreyfus with her: the Indianapolis 500.

O'Reilly Schell entered two of their Maseratis in the 500-mile race, and the trip seemed promising. Wilbur Shaw had won the race the previous year with the same Maserati O'Reilly Schell would be bringing, and it also got her out of the France.

The outing wasn't a massive success. Dreyfus didn't understand that, at Indy, the car qualifies, not the driver, so he and his teammate (known only as Le Bègue) shared the same chassis and split the 500 miles in half. They finished 10th. O'Reilly Schell sold the cars to Lou Moore. She helped Dreyfus and Luigi Chinetti, who had come along with the team as a mechanic, obtain their American citizenship.

In the spring of 1940, members of the Gestapo raided the headquarters of the Automobile Club de France and seized all the records of France's participation in Grand Prix racing. The goal was to write the country out of motorsport history, and in many respects, that goal was achieved. Those records have never been found, and the head officer reportedly told the clerk that, "We will write the history now."

But before she had left, O'Reilly Schell had disassembled her Delahayes and stored the parts in a variety of hidden places. Those, Germany never found.

O'Reilly Schell's life after that is quiet. It's unclear what she did in America, but after the war, she did return to Monte Carlo, and it was there she died in 1952 at the age of 55. Her son, Harry Schell, went on to become the first American to compete in postwar Grand Prix racing, which became known as Formula One. Harry Schell was one of the first advocates for motorsport safety. Schell was killed during an event at Silverstone in 1960, when he was 38.

Lucy O'Reilly Schell was undoubtedly a pioneer. In the interwar period, it wasn't desperately uncommon for women to race, but they certainly didn't go on to become Grand Prix team owners and million-franc prize winners. They didn't leverage their reputation in the motorsport world to give an unfairly blackballed Jewish driver a chance to compete. They didn't use racing as a way to help that man later find a home in a new country. And that is what makes Lucy O'Reilly Schell an icon of motorsport.