A Brief History Of Gasoline: They Lied About The Science

Part 7: Opportunity knocks in Dayton, and GM builds a creation myth around leaded gas

As today's installment begins, gunpowder powerhouse and expanding chemical giant DuPont and its future ward, General Motors, will soon come together, with the duPont family very much in charge. Along with Standard Oil of New Jersey, today's ExxonMobil, they will soon be in the business of selling leaded gasoline, with a joint venture known as Ethyl Gasoline Corporation. But their lead-loaded assault on the planet won't get off the ground without the services of two engineers in GM's employ – one electrical, one mechanical; one well-known, one less so, but both towering figures in the destructive art of 20th century pollution – Charles Kettering and Thomas Midgley, Jr. And the success of selling this deadly product in to an unsuspecting world will require Ethyl to craft its own Creation Myth.

This is the eighth story in a series of stories on the history of gasoline. So far, Jalopnik's tech coverage has been focused primarily on the emergence, or reemergence of the electric vehicle. One of the primary arguments levied against electric cars and electric charging infrastructure has been that bringing both into the mainstream would take significant investment from private and public actors, and that this has not generally been politically palatable in the United States. In this multi-part series, award-winning journalist Jamie Kitman will lay out how American corporate and government entities have been cooperating on a vastly more costly, complex and deadly energy project for well over a century: gasoline.

Here are our previous parts:

Part 6: The Original Sin Of General Motors

Part 5: Better Things For Deader Living ... Through Chemistry

Part 4: How Standard Oil Got Away With It

Part 3: How Standard Oil Built Its Toxic Monopoly

Part 2: They Trashed Pennsylvania First

Part 1: How Gasoline Got Into Our Lives

Prelude: A Century And A Half Of Lies

"Little did the antiknock research pioneers realize the tremendous contribution they were to make to engine progress and to better living for everyone." —Thomas A. (Tab) Boyd.1

Charles Francis Kettering, his associates and the corporations they served would make history with their new invention, leaded gasoline. However, only part of this was due to the historically and medically significant fact of their introducing a product that would in time surely blanket the earth in finely diffused, neuro-toxic lead dust. Ethyl and its founders also set out to make history literally; that is, very early on and for the rest of the century, they wrote and underwrote a carefully crafted history, defining terms and laying out a fantastical catalog of virtue – their product's and their own – the folksy stoicism, their magnetic and magical spirit of invention, all grounded in topflight science and practical smarts. Their story would then be piped into the nation's homes, libraries and academies, as gospel. Chances are, if you were exposed to it, much of what you think you know about leaded gasoline is untrue.

Placed into circulation then repeated uncritically for generations to come, theirs' was a yarn of heroic lives and gung-ho times, handcrafted with the help of the leading advertising Brahmins and marketing deadeyes of their day. From Madison Avenue to Wilmington and Detroit's grand thoroughfares, there emerged a paid-for history that appeared in books, pamphlets and magazine articles, recounting in great, selective detail the search by Kettering and his lab for a commercial anti-knock. These tales would set out for posterity events as they preferred them told, and would be central to the marketing of leaded gasoline – a vital, modern product, the citizenry were assured, that owed its existence to good old American ingenuity and the plain-spoken wisdom of ordinary country folk like Kettering and his right-hand man, Thomas Midgley, who together would become leaded gasoline's public face, even as they were quietly eased out of the actual day to day business by their corporate masters.

Along with sermonizing speeches, copious magazine puff pieces and jaunty remembrances by its poster boys Kettering and Midgley, sponsored radio programs, newsreels, radio spots and television advertising all served to set out the basics of the lead gasoline story, as GM, DuPont and Standard Oil preferred it told, minus the parts they didn't care for. The cumulative effect was to create an Ethyl echo chamber, in which one, basic, upbeat story successfully monopolized the popular imagination and the historical literature, to the exclusion of any other viewpoint. This in spite of the fact that a much darker view of the lead gasoline experiment was there to be told from its earliest days. But after momentarily hearing out its critics – the public health community, the doctors, research scientists and trade unionists who told of its likely hazards and opposed leading the gasoline supply –the government, the media and, by extension, the public largely ignored these objections for forty years and more, leaving a vacuum Ethyl filled.

Together with specious medical and scientific studies they'd finance, the sea of marketing material the additive maker, its parents and minions would create comprise by far the largest part of what there was to read and see about lead gasoline and its introduction. Taken in sum, they constitute the Ethyl Creation Myth.

The development of this self-regarding history was a farsighted commercial innovation in itself, one of the great marketing stratagems of the twentieth century. Fifty years before E&J Gallo Winery and the Hal Riney ad agency created Bartles & Jaymes — a couple of fictional old-timers who'd supposedly come up with a countrified line of fruit-flavored wine coolers down on the farm — Ethyl was telling America warming tales of crusty but loveable "Boss" Kettering, his devoted sidekick, Thomas Midgley, and the nifty guys in the lab.

An appealing admixture of downhome affability and unwarranted scientific pomp, the stars of Ethyl's Creation Myth were quickly deployed in service of the Orwellian sales proposition that was lead gas, a wildly dangerous, easily replaced product peddled as hygienic, wholesome, and essential to modern life. Nothing less than a glorious, pre-fabricated history with a strong government imprimatur could help the boosters of tetra-ethyl lead achieve the widespread consumer acceptance it enjoyed and this is what they sought and received.

Ethyl's set piece starts with the unsubstantiated assertion that there was an urgent need for a "magic bullet" gasoline anti-knock additive. Knock was on the rise. Enter the laboratory of inventor Charles Kettering, a "screwdriver and pliers" sort of guy grown up on the farm, set by him to searching furiously for such a thing. After years of exacting study and several honorable dead ends, it continued, an exciting discovery by his eager assistant Tom Midgley arrived to do something just short of saving civilization: the perfect anti-knock, tetra-ethyl lead (TEL.) It was, the official line continues, the ideal, rational scientific result. Then, as a service to the human race that would only incidentally reward its investment in spades, GM deigned to manufacture TEL for use in gasoline, calling in learned colleagues at DuPont and later Jersey Standard for assistance, and arranging to make it available around the world. By these acts, Ethyl thereby unleashed millions of horsepower from millions of engines that might now run higher compression ratios (here is our primer on what compression ratios are and why higher is better) making them not just more powerful but more economical, immeasurably enhancing society's wealth and well-being. Ethyl's Creation Myth proposed that in this product, from its days as germ of an idea to its ubiquitous presence in modern life, lay the perfect demonstration of the value of stick-to-it-iveness, corporate research science and the American free market in action.

With nary a discouraging word, overlooked in Ethyl's creation tale are the myriad worrying and incontrovertible facts about lead gasoline from a health and safety perspective and a fundamental truth – it was a lousy idea from the start. Adding it to gasoline shortened and diminished billions of lives and it fouled engines and Ethyl's managers knew or were warned of all of it. While historians must be careful not to impute modern knowledge to those working 100 years ago, the record shows that it simply won't do to say they were unaware of what hazards their new business entailed. They knew most of them well.

Dayton, Ohio. A bloody battleground in the French and Indian wars fought not long before the American Revolution, a swinging city of industry by the end of the 19th century. Expanding steadily from the earliest days of the mechanical revolution (thanks to a canal connecting it with Cincinnati to the south and, later, Lake Erie, to the north,) the city saw its vitality cemented with the arrival of the railroad. A pair of local bicycle mechanics, the Wright brothers, achieved lasting fame when they kept a flying machine aloft above the beaches of Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, for a few, fleeting moments in 1903. Upon their heroic return to Dayton, they set about building airplanes commercially, erecting factories and laying airfields not far from the many plants, mills and satellite auto parts operations that would now cause the city to hum.

Young Thomas A. Midgley, Jr., arrived in Dayton by rail shortly after being graduated from Cornell in 1911 with a degree in mechanical engineering. He'd signed on with one of the city's biggest employers, National Cash Register, today's NCR. Here Midgley would first encounter Charles Franklin Kettering, a tall, lanky fellow, the child of farmers and a former schoolteacher from the hills of northern Ohio with thick spectacles and a high voice but an outsized personality. Having made good in the city as a pioneering automotive electrical engineer, he was well into the process of establishing a national reputation at the age of 35.

A little more than ten years after they met, these two personable engineers — one mechanical and the other electrical — would be heralded as the fathers of leaded gasoline, one of the most momentous chemical inventions of the 20th century. And if they weren't actually its inventors — an unpublished Ethyl history suggests a pair of assistants got to it first — they would be its most ardent promoters.

CHARLES KETTERING, SELF-STARTER

C.F. Kettering's ticket to ride was punched promptly after arriving at "The Cash," as NCR was known locally, in 1904.2 He applied a simple but profound realization of the electrical engineering community at the turn of the 20th century — that a small electric motor could be designed to deliver a big burst of power for a very short time, just long enough to perform the job of a much larger motor. Using such a miniaturized motor, Kettering in 1906 built the first electrically powered cash register. The productionized NCR Class 1000 register that followed his prototype would remain in production for 40 years.

An entrepreneur by nature, Kettering sought business challenges after hours, and he began to moonlight, setting up in 1909 with a fellow NCR electrical engineer, Edward A. Deeds.3 During his remaining days at The Cash, he'd recall, "I didn't hang around much with other inventors or the executive fellows. I lived with the sales gang. They had some real notion of what people wanted."4

Kettering the closet salesman was also not above using inside information to obtain an extra-accurate notion of what people wanted, especially now that he'd decided he'd rather be working for his own account. Deeds' NCR assistant, Earl Howard, had taken a job with Henry Leland's Cadillac division at GM and let slip the fact that the automaker was unhappy with the ignition systems it was using in its new models. Soon afterwards, Kettering and Deeds' Dayton Engineering Laboratories Company (DELCO), makers of automobile ignitions, was opened for business.

Located in Deeds' barn behind the house at 319 Central Avenue, the startup claimed a mere $1,500 of Kettering's capital. But the basic ignition system he'd hatch for the occasion, with its innovative holding coil, was a winner. Still in use today, it filled DELCO's order books (Leland contracted for 8000 sets) from the start.

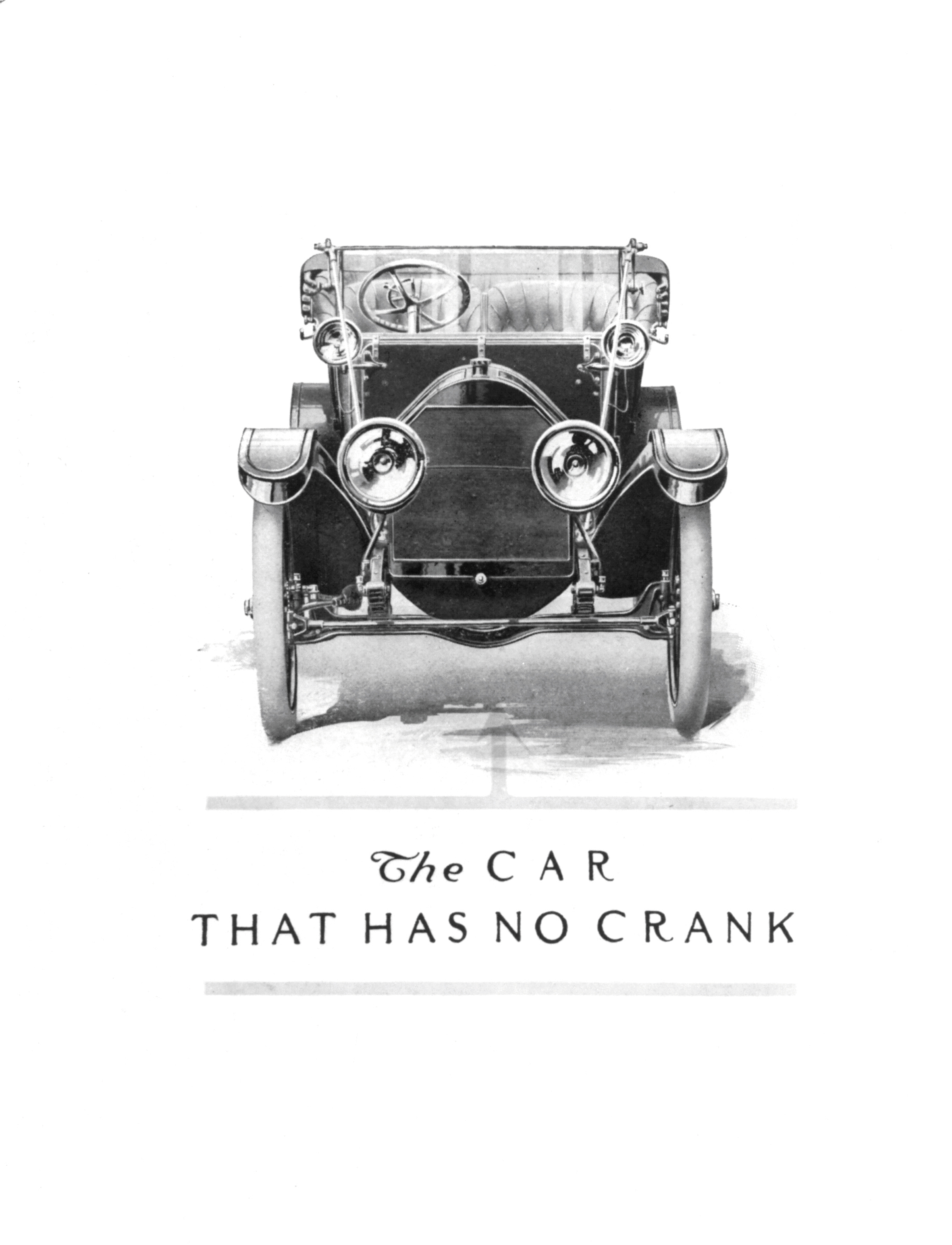

But as a giant, money-making machine with its own manufacturing capability, the DELCO operation didn't pick up real steam until the arrival of Kettering's other legendary contribution to the youthful automobile industry, and surely his greatest hit: the self-starter. By following the same principle (small motor, high torque) used in the electric cash register, Kettering would receive credit for kicking the stuffing out of the prevailing theory that any reliable automotive self-starting device would have to be so large it would practically require its own trailer.5

According to one admiring, oft-repeated account, the inventor was moved to imagine the accessory following the accidental death of Byron T. Carter. Head of GM's short-lived Cartercar division, Carter had stopped to help a woman in distress. Her Cadillac car had stalled, but when he tried to start it for her, he failed to advance the car's ignition and was struck by its hand crank when the motor kicked back, breaking his jaw. Carter died from complications. Meeting up with a grief-stricken Henry Leland, a friend of the deceased, head of Cadillac and a much-respected automotive mind and senior statesman whom Kettering naturally admired, the young engineer was asked by his elder whether he could not do something about this cranking menace. The result, this story goes, was the automatic starter.6

The truth is more prosaic and somewhat less heroic, and in what would not be the last time, Kettering's starring role is embellished. Kettering did not invent the self-starter. Rather, he took an existing idea and had his people ready it for production. Though the story of his exclusive authorship is forever repeated, Kettering's Boswell, T.A. Boyd, a GM lifer and chemical engineer who'd live to be 100, noted in one of his many fond reminiscences that someone named Clyde J. Coleman was first to apply for a patent specifying the starter's key features, granted in 1903. U.S. Patent No. 145-157 was then sold to one Conrad Hubert of New York, who was soon after persuaded by Deeds to issue a license to DELCO; Hubert did not view the electric self-starter "of much practical importance."7 How wrong he was, though the invention of the flashlight and the EverReady Company he subsequently founded surely kept Hubert busy.

Coleman had not made adequate provision for torque or disengaging the starter once the engine was running,8 among other reasons his invention wasn't ready for service, and correcting these fatal shortcomings would be DELCO's task.

Kettering didn't actually get the starter to disengage from the engine's spinning flywheel, so he'd completed only one of the two necessary upgrades. Continuously engaged, Kettering's starter was engineered to work as a generator during operation. It wasn't ideal and in 1913, Bendix would design a starter that disengaged from the engine, but DELCO was already on its way.

The gestation was slow and grueling. One worker who'd pass long hours in the Deeds' barn recounted that a phonograph was brought in to kill the boredom while they endlessly experimented. But there was only one record – "When You and I Were Young, Maggie"–and it played over and over.9

We can only wonder whether anyone ever sought to locate another platter and, if not, why not, because it would be close to two years before the self-starter was ready to go into production. But when it came, it was a game-changing development that would deliver Kettering his first real fortune.

Getting rich persuaded Kettering like many of his generation so blessed, that he deserved his outsized success, though unlike many he rarely credited the Almighty. Rather, sudden wealth convinced him of the wisdom of his own intuition and hunches, and the powerful force of his own will. It led him to inflate the value of directed corporate research to saintliness and to revere technology as the pathway to all human progress. It reaffirmed for him, too, the underlying wisdom of American capitalism, a system for which he'd now become an ardent cheerleader. "I am for the double-profit system, a reasonable profit for the manufacturer and a much greater profit for the consumer," he liked to say.10 As with leaded gasoline, it led him to leap before looking.

The new self-starting apparatus had an immediate effect on car sales; many have called it socially liberating and to the extent the automobile was liberating, so it was. Automatic starting enabled and encouraged many Americans to drive for the first time. No longer was significant upper body strength needed to start a car. Malcolm Bingay, a long-serving editor of the Detroit Free Press and industry cheerleader offered with the condescension typical of his era that by developing the self-starter Kettering "did more to emancipate women than Susan B. Anthony or Mrs. Pankhurst or all the other valiant gals who get the credit he deserves."11

In addition to adding millions to the motoring ranks and putting many a chauffeur out of work, the starter has also been credited with hastening the demise of steam and electric cars by proving the superior economy, convenience and performance of gasoline-powered machinery. As Kettering put it, "Inside of two years it was pretty hard to find anyone who wasn't thoroughly sold on the idea. Cars that were not equipped with the new device ... simply faded right out of the picture."12

No doubt starting cars by hand crank was a real bummer and genuine hazard; you wouldn't buy a gasoline car without a starter, once they became available, if you were in your right mind. Still, when considering the demise of automobiles that weren't powered by gasoline, one mustn't give the starter all the credit. The noisiest adherents of internal combustion and gasoline — the oil companies and makers of gasoline cars — already had every incentive to crush the battery- and steam-powered competition on their own, and by any means necessary.13 Moreover, they were well on their way to so doing, long before the self-starter arrived to administer the coup de grace. The same might be said of their motivations during the next century, which they'd spend bad-mouthing the use of alternative fuels — such as ethanol — in internal combustion engines and, later, electric vehicles. The self-interested foundation for their technological choices, their viewpoint and biases, far from being well hidden, have always lurked in the foreground.

There is, however, no overstating the fact that the automatic starter did wonders for DELCO (spun off by GM in 1999 and today part of the Borg-Warner auto parts-making enterprise) and for Kettering.14 Thanks to its new invention, they would receive their first really substantial order in 1911, for $10 million, courtesy of General Motors. And Kettering was brought to the attention of General Motors' new managers – the aforementioned James Storrow and the Boston bankers he represented— as well as every competing car manufacturer. GM had ordered 12,000 starters for its 1912 model Cadillac.15

SCHOOL OF HARD KNOCKS

The new Cadillac hit the streets amid much excitement, the first ever cars to be equipped with a self-starter and DELCO's improved ignition system. Alas, before the heads of DELCO staff could swell too greatly with pride, customer complaints started pouring in from the field. Motorists and mechanics were reporting a pronounced and disconcerting noise when running the Cadillac engines under load, such as while accelerating. American engineers would identify the untoward metallic din as the result of irregular combustion, something they called "knock," "ping" or "pinging;" the English called it "pinking."

Unfairly in Kettering's eyes, industry scuttlebutt, even that circulating among certain GM personnel, blamed his new electrical systems. Unbeknownst to them, the real culprit was the fact that Cadillac had raised the "compression" of its engines, to increase power and efficiency, but that when used with gasoline of inadequate octane, high compression caused knock, the sound of gasoline exploding at the wrong time in the combustion cycle.

Low octane gasoline, insufficiently resistant to explosion, was very much norm in those days, and, though some might have had a visceral appreciation of the issue, the underlying science was not understood. The concept of octane hadn't even been invented. And even after a cause-and-effect relationship — between gasoline's explosive properties and appropriate ratios of compression — became clear, knock was still not fully understood.

American motorists had not suddenly grown more discerning. There had been a rise in engine knock. High-compression motors, increasingly in use, caused knock with certain lesser gasolines. And though few outside of the oil industry realized it, motorists were suffering from the properties of the gasoline being sold. Erratic at the best of times, quality was dwindling steadily as car sales accelerated wildly.

Demand for automotive fuel would explode in the Teens, straining supply; intermittent petroleum shortages were already being experienced. Oil was increasingly coming from new fields, (Standard Oil, for instance, was increasingly relying on Mexican crude, as Pennsylvania and Ohio fields dried up) often with less desirable characteristics.16 Refiners were ill prepared for the manipulations of the new crudes that were needed to make gasoline of uniform quality.17 However, one solution that appealed to them was refining petroleum to increase its yield of gasoline fractions, through cracking and the Burton-Humphries process of catalytic cracking, discovered in 1913. This improved supply but the penalty was often a smellier and lesser gasoline — one given to exploding prematurely in the cylinders and causing knock. The property that was in short supply in gasoline would come to be called octane.

Car sales continued to multiply, and DELCO's business grew rapidly alongside them, each car needing a starter. But, as Kettering told the story in years to come, from this point on, it was knock — as a subject of intellectual inquiry — that really interested him. He was determined to uncover its cause and directed his laboratory to get on with it and he and they would beaver away until they did. Or so he said.

In truth, Kettering's interest would fade in and out over the course of years, and that interest, though defensive at first, then primarily academic, became in later years openly pecuniary, as we shall see in future installments.

Kettering claimed he had his reputation to uphold. "DELCO ignition was my own child," he wrote. "If it was causing engine knocks — which I was not prepared to admit until somebody could prove it — I wanted to know how I might remedy the defects behind the trouble. So while we did not omit the precaution of making a few comparative tests on identical cars, using various types of ignition to prove that Delco was not guilty, we set about studying combustion in automobile engines and especially combustion in relation to automobile knocks."18

GM continued to do substantial business with DELCO and, in 1916, one year after Pierre DuPont had joined John Jakob Raskob in buying a huge interest in General Motors and shortly after William Crapo Durant engineered his own miraculous return to its boardroom, the corporation's association with Kettering was formalized, largely owing to the intervention of duPont. An MIT-trained engineer, he rated a technical fellow like Kettering highly, drawn to his optimism about the future and contagious enthusiasm for technology and the profit motive. Like music to a duPont's ears, Kettering unwavering and pithily expressed view of the purpose of scientific research — "...[A] bank account in the black is the popular applause of a scientific accomplishment" — dovetailed comfortably with the hopes and dreams of his voracious future masters and collaborators.19

In 1908, just six percent of the nation's roads had gravel or hard surfaces.20 But the nation's first concrete highway was laid in Wayne, Michigan, in 1908, and once paved, roads never become unpaved; they only beget more paved roads. GM, DuPont and all concerned had reason to be bullish. Congress appropriated $75 million in 1916 to help spur rural road construction, for the avowed purpose of helping farmers in isolated areas get their crops to market via the railheads in bigger cities.21 Who knew paved roads would in time kill the railroads and railheads alike, leading to more cars and more roads? As it happened, quite a few people knew.

Kettering, mindful of the auto industry's bright prospects and receptive to duPont's generous overtures, formally bound his destiny to that of GM in 1916.22 So attractive were the terms offered Kettering and Deeds — including a generous valuation of their Dayton properties at $9 million, (the equivalent of over $225 million in today's money,) and a promise to keep their existing operations in that city running — that duPont persuaded the wily inventor (putative author of 140 patents in his lifetime)23 and his partner to subsume DELCO within United Motors, the parts business Durant had been growing on the side. As an additional courtesy and to help him better focus, GM picked up several of his sundry non-automotive business interests in Dayton as well. Kettering was a powerful GM stakeholder now, made rich by the duPonts and situated to get richer. Such targeted largesse, per Hamilton Barksdale's dictum about keeping senior executives tied to the corporation through generous financial incentivization, guaranteed Kettering's rapt attention as a GM manager for the rest of his professional life.24

WAR PROFITS

Being a giant explosives-maker, DuPont gave GM an early window into the War in Europe long before the rest of America had turned its attention in that direction. Already raging, both sides in the war were supplied by DuPont and its explosives associates, and big profits were being had in the process.

Yet World War I — and America's involvement in it — would bring the issue of knock into clearer relief as the malady was found to plague airplane engines, too, causing the Kettering lab's sporadic research in the area to accelerate with government funding. In the years ahead, DuPont itself would also study the internal combustion process, as part of the massive and rapidly expanding research effort it launched while relying on its explosives windfall to fund its move deeper into the chemical realm. On the topic of knock reduction, however, GM's research department, smaller, hungrier and more in need of justifying itself, was easily the more aggressive. It was, too, more impulsive, more impatient, less capable and less educated, the impacts of which would be felt soon enough, through a series of fantastically misguided "cures" it championed.

Kettering had moved his early combustion studies to a new company he formed in 1916, Dayton Research Laboratories, soon renamed the Dayton Metal Products Company, Research Division, and finally, in 1919, the GM Research Lab. To run this new shop, he brought along his old Ohio State professor, Dr. F.O. Clements, whom he'd originally tapped to work at NCR. And he'd invited to join the cause Thomas Midgley, Jr., the Cornell graduate and former NCR recruit who'd returned to Dayton after completing a brief layover in Chicopee Falls, MA, where he'd gone to try and help turn his father's ailing tire business around, without success.

Charles Kettering's professional life would span more than sixty years, lasting until his death in 1958, by which time leaded gasoline was found everywhere on earth. His would be a career marked by accolades and encomiums as well as for his substantial accumulation of personal wealth, culminating in the formation of both the C.F. Kettering Foundation and, subsequently, (when he pooled charitable giving with his longtime boss and friend, Alfred P. Sloan,) the Sloan-Kettering Memorial Cancer Research Center (ironic, in that leaded gasoline is itself a carcinogen.)

Kettering was dubbed a prophet of progress and profit, a shorthand descriptor with which he would not disagree — and may well have coined. For he saw the two as inextricably linked, though we might not always agree with his notion of progress. Any fair telling of the century in which Kettering had a large hand would note that the change he helped foment hasn't always been for the better.

Tributes and rewards aside, as often as not, Kettering's success typically rested on the work of others, who conducted experiments in laboratories under his general direction, or the men in the factories and office blocks of General Motors Corporation, in which Kettering held considerable equity.

Indeed, as an inventor, Kettering's own great discoveries were few in absolute number, though his stature as a public genius was enormous. Thomas Edison and Henry Ford were America's reigning inventor deities when Kettering joined the burgeoning field of industrial applied research and most remember them more readily today. But Kettering would, for a time, overtake both men in the sphere of public affection. Not as inventive as Edison and no more visionary than Ford, he was less cranky and more personable than either, and also usefully younger, outliving them both to make it deeper into the radio and newsreel ages, where his magnetic personality could shine for all to see and hear, the last of America's great tinkerer inventors.

Central to Kettering's popularity was a winning public persona, which scanned as modest and self-effacing, disarming if tart. Privately, he was also prone to angry outbursts, arrogant pronouncements and bouts of self-pity, while his stubbornness and willingness to speechify interminably at the drop of a hat, celebrated in public utterances by those closest to him, also had obvious downsides, which they noted in their private correspondence – he really could bore on.

But a glowing reputation was made possible by Kettering's charisma, confident showmanship and easy, "aw, shucks, ma'am," command of the scientific (and quasi-scientific) subjects he touched upon during his frequent public orations, over 2000 in his lifetime, with which he sought to educate, entertain and wow his audiences.

Longtime GM chairman Alfred Sloan, with whom he'd remain friendly for his entire life, affectionately described the man he knew as "Ket" as a "farmer, school-teacher, mechanic, inventor, scientist, social philosopher and, superimposed upon all—master salesman."25 A TIME magazine cover story on him in 1933 enthused he was "the greatest salesman of science this country ever produced."26 His motivational speaking skills were advanced and with the new medium radio increasing their potential reach, it was perhaps inevitable that Kettering the magnetic salesman/inventor would be let loose on the nation.

"Boss" Kettering would achieve a broader fame in his lifetime and enjoy a happier and more graceful old age than his sometime head researcher Midgley, an amusing personality in his own right who would be credited by Kettering for three of "his" own most famous "discoveries": leaded gasoline and the refrigerant known as Freon, whose discovery gave birth to the third – a new generation of gaseous compounds known as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs.) Used as refrigerants, cleaning solvents, and aerosol propellants, they are found also in just about every piece of plastic foam ever made. Best known today as a major cause of stratospheric ozone depletion, CFCs are largely outlawed. All of these Midgely brainstorms would achieve worldwide ubiquity. Yet although they'd bring this native son of Beaver Falls, PA, much wealth, along with the highest honors the industrial and chemical societies of his day had to offer, none has made Thomas P. Midgley, Jr. an enduring household name. Which in retrospect might have been something to be grateful for.

Midgley's first work at DELCO had been to engineer a hydrometer to measure the strength of the acid in the built-in storage battery of its farm lighting units, but, after his initial objection to reassignment was overruled, he was relegated to studying engine knock, work that continued when General Motors bought in. T.A. Boyd, the good-natured and literarily prolific chemical engineer who would go on to chronicle both Kettering and Midgley's lives, was detailed at this time to work with the younger man.

Knock was no longer just plaguing automobiles, but also the stationary internal combustion engines which ran DELCO's new farm lighting systems. These portable generators were a popular means of electrifying farms and other dwellings in remote settings in the years before universal electrification. They struck an important grace note in rural life and increased the breadth of Kettering's popularity even further. But, when operated on kerosene or paraffin, as they often were during the First World War — by people looking to avoid newly hiked gasoline taxes (and to satisfy local fire codes which might demand use of fuels less explosive than gasoline) — their engines knocked badly.

It was around this time, Kettering would later recall in innumerable forums, that he became convinced fuel had to be the problem in knock. For which there had to be a solution. This insight is often cited as a key example of Kettering's genius.

Yet this telling, which has been repeated by lead gasoline interests in America for the better part of a century, would overlook the fact that this truth about the explosive properties of fuel was first revealed to the world by Sir H.R. "Harry" Ricardo, the great British engine designer and internal combustion theorist of whom Kettering and Midgley were surely aware. The engine consultancy he founded, Engine Patents Ltd., survives through the present day as Ricardo, PLC. It also overlooked the fact the refineries knew how to make better gasoline, but often chose not to, because of cost – be it drawing from superior crude oil stocks or through additional investments in refining and capital equipment purchases.

It is worth pausing to observe that this sort of minor mis-telling of history is neither isolated nor inadvertent. As their story line moves forward, the inconsistencies expand and accumulate as the lead gasoline boosters seek to explain the origins of leaded gasoline. They begin their story on an Ohio farm where Charles Kettering is born and continue it in a barn behind E.A. Deeds' house, because it sounds best that way and this is how they choose to tell it. They overstate the roles of Kettering and Midgley and obscure their motives and those of their employers.

Let's pause to remember how and why the idea of gilding the facts and adding and omitting key details must have seemed so advisable for the people selling leaded gasoline in.

A fuel that promised to blanket the earth in a vapor with toxic lead dust was hardly an easy sell in the wake of the gas attacks of World War I, which had scarred millions and horrified many more. It was the type of product that occasioned not just a few over-the-top brochures commending its advantage, but rather a full, frontal assault on the public consciousness in an attempt to steer the discourse.

Rendered paraplegic towards the end of his life, Midgley was diagnosed with polio before his premature death at the age of 55, in 1944. However, massive exposures to lead and leaded gasoline throughout his adult life, as well as Freon and other ungodly chemical compounds, often willfully ingested, couldn't have helped his life expectancy, nor could a lifetime's taste for strong drink.

Far beyond the question of whether they injured him personally, Midgley's famous inventions blossomed into global environmental disasters, perhaps some of the most chilling demonstrations of the laws of unintended consequences the 20th century had to offer.

Jamie Kitman is a NY-based lawyer, rock band manager, picture car wrangler, and automotive journalist. Winner of the National Magazine Award for commentary and the IRE Medal for investigative magazine journalism, he has a penchant for Lancias and old British cars, and is a World Car of the Year juror. Follow him on Twitter @jamiekitman and on Instagram @commodorehornblow.

Endnotes

1. Ralph C. Champlin, HISTORY OF THE ETHYL CORPORATION: 1923-1948, Historical Summary, New York, Ethyl Corporation, department of Public Relations, 1951 (Third Draft, unpublished manuscript, mimeographed for distribution.) P.10.

2. NOTE: Like DuPont, GM and Standard, NCR was a trust. Created by John Henry Patterson in 1884, it employed similarly aggressive strategies to vanquish its competition, cornering 95% of the market for business machines in America by the time an action was brought against it under the Sherman Antitrust Act. Convicted in 1912, Patterson and 25 executives were sentenced to one-year prison sentences, with no chance of parole, but these were overturned on appeal.

3. NOTE: Early in his career, Deeds left NCR to design and build the Shredded Wheat factory, the so-called Palace of Light, at Niagara Falls, NY. He would later return to NCR, and was one of the 25 NCR executives – along company president John Henry Patterson — convicted of antitrust violations. In January 1919, court martial proceedings against him would be dropped by the Army, which chose to overlook the finding of a presidential committee which had alleged that Deeds, a large GM and United Motors shareholder, had been illegally trading with United Motors after falsely stating that he had disposed of his shares. "ARMY EXONERATES COLONEL E.A. DEEDS," New York Times, Jan. 17, 1919, P, 7.

4. Boyd, T.A. Professional Amateur: The Biography of Charles Franklin Kettering, New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1957, p.53.

5. The starter idea was criticized by some of the electrical orthodox at its inception, who couldn't get over the fact that it was pumping five times the current thought advisable through wires for continuous use. Boyd, T.A. Professional Amateur: The Biography of Charles Franklin Kettering, New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1957. p76

6. Boyd, T.A. Professional Amateur: The Biography of Charles Franklin Kettering, New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1957, p.68-69.

7. T.A. Boyd, Professional Amateur: The Biography of Charles Franklin Kettering, New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1957, p.75.

8. Rockman, Howard B., "Intellectual Property Law for Engineers and Scientists," Wiley-Institute of Electronic and Electrical Engineers (IEE,) 2004, p.318.

9. T.A. Boyd, Professional Amateur: The Biography of Charles Franklin Kettering, New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1957, p.70.

10. Loeb, Alan P. "Birth of the Kettering Doctrine: Fordism, Sloanism and the Discovery of Tetraethyl Lead," Business and Economic History, Volume 24, No. 1, Fall 1995, p86

11. T.A. Boyd, Professional Amateur: The Biography of Charles Franklin Kettering, New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1957, p.82

12. T.A. Boyd, Professional Amateur: The Biography of Charles Franklin Kettering, New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1957, p.77.

13. For an excellent recitation of this, read Edwin Black's Internal Combustion: How Corporations and Governments Addicted the World to Oil and Derailed the Alternatives, (New York: St. Martin's Press, 2006, pp.408).

14. "Should You Dump Delphi?," Business Week Online, June 7, 1999, . NOTE: GM's ties to Delphi's remain — along with its financial and ethical obligations particularly in the area of pensions — remain considerable.

15. T.A. Boyd, Professional Amateur: The Biography of Charles Franklin Kettering, New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1957, p.72.

16. Gibb, George S.; Knowlton, Evelyn, "History of the Standard Oil Company (New Jersey): The Resurgent Years, 1911-1927, New York: Harper & Bros., (under the auspices of the Business History Foundation, Inc.,) 1956. P. 127. Heavy Mexican crude "differed very greatly in properties from the domestic crudes that the New Jersey and Louisiana refineries had been set up to run and required correspondingly greater changes in equipment and methods."

17. Gibb, George S.; Knowlton, Evelyn, "History of the Standard Oil Company (New Jersey): The Resurgent Years, 1911-1927, New York: Harper & Bros., (under the auspices of the Business History Foundation, Inc.,) 1956.P.127. They write: "since no two crudes are alike, continual processing alterations were required in the different refineries."

18. Kettering, C.F., "Research, Horse-Sense and Profits," Factory and Industrial Management, Vol. LXXV, Number 4, April 1928, p. 736.

19. Leslie, Stuart W., Boss Kettering: Wizard of General Motors, New York: Columbia University Press, 1983, p207

20. Kyvig, David E., Daily Life in the United States, 1920-1940, Chicago, Ivan R. Dee, 2004, p.48.

21. Kyvig, David E., Daily Life in the United States, 1920-1940, Chicago, Ivan R. Dee, 2004, p.49.

22. Leslie, Stuart W., Boss Kettering: Wizard of General Motors, New York: Columbia University Press, 1983, p116.

23. "Engineering genius Charles Kettering dies after stroke," The Birmingham Post-Herald, Nov. 26, 1958.

24. Alfred P. Sloan, My Life with General Motors, (New York: Doubleday & Co., 1963) p.73.

25. Sloan, Alfred P., My Life with General Motors, New York: Doubleday & Co., 1963, p. viii.

26. Leslie, Stuart W., Boss Kettering: Wizard of General Motors, New York: Columbia University Press, 1983, p. 340.