A Brief History Of Gasoline: How Standard Oil Built Its Toxic Monopoly

Standard gave the government every piece of evidence on how corporations lie, cheat, and poison the country. It's still getting away with it today.

Before you can begin selling one of the deadliest products man has ever made – leaded gasoline – it helps that the corporate persons have reckless and ruthless pasts. Over the course of its next four installments, Jamie Kitman's Brief History of Gasoline will examine three of the main actors in the saga that brought us tetra-ethyl lead and a host of other unsavory gasoline additives. DuPont and its longtime corporate ward, General Motors, who invented leaded gasoline, will be considered in the weeks ahead, but here, Standard Oil of New Jersey, the company affectionately known today as ExxonMobil, is in the spotlight. It's a long story, but it began a long time ago and it ain't over yet, so it bears telling.

This is the fourth story in a series of stories on the history of gasoline. So far, Jalopnik's tech coverage has been focused primarily on the emergence, or reemergence of the electric vehicle. One of the primary arguments levied against electric cars and electric charging infrastructure has been that bringing both into the mainstream would take significant investment from private and public actors, and that this has not generally been politically palatable in the United States. In this multi-part series (here is the history of how the oil industry made its blueprint for pollution trashing Pennsylvania first), award-winning journalist Jamie Kitman will lay out how American corporate and government entities have been cooperating on a vastly more costly, complex and deadly energy project for well over a century: gasoline.

STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURE: THE RISE (AND RISE) OF THE STANDARD OIL COMPANY

"Actual experience has shown that these men are, from the standpoint of the people at large, unfit to be trusted with the power implied in the management of a large corporation."

— Theodore S. Roosevelt

Born July 8, 1839, John Davison Rockefeller, the son of William Avery Rockefeller and Elisa Davison, would be remembered at the time of his death nearly 100 years later not just for the sumptuous fortune he left behind as the world's first billionaire. Or for the colorful roadmap of wildly unscrupulous corporate behavior which Standard Oil, his life's work and the roaring engine of his great prosperity, devised. Many would recall his philanthropy, Baptist piety and fidelity to his wife. He was a complicated dude.

In all these ways except the complicated part, the richest man in the world was most unlike his own father, a quack doctor and patent medicine salesman who maintained two wives and two households before abandoning his first family to live with a second under an assumed name. So improbable (and titillating) was the contrast with the son who became richest of all the world's citizens that the man who would in latter life call himself Dr. William Levingston — a sobriquet adopted, in part, to evade a statutory rape indictment dating from the 1840s – spent a fair bit of his seniority dodging reporters before finally passing away at the ripe age of 96. (Much to his son's chagrin, all would be exposed in 1908, two years after the old man breathed his last, in Joseph Pulitzer's paper, the World, in a piece entitled "Secret Double Life of Rockefeller's Father Revealed by the World.")

Reared in hardscrabble upstate New York, the young John D. Rockefeller moved to a Cleveland suburb at the age of 14. Given his trying childhood and early lifetime of near penury, neither Rockefeller's severe personality or outsized ambition was surprising. He was, time would tell, a man possessed. As Ron Chernow's thoroughly readable chronicle Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr. notes, a contemporary biographer would learn that the youthful Rockefeller once boasted to a senior business associate, "I am bound to be rich, bound to be rich – BOUND TO BE RICH!" Then, he slapped his knee hard. And rich he would be.

Dropping out of high school, he hurried through a six-month college business course in double time, and, following a brief stint as a clerk for a local shipping firm, the 19-year-old Rockefeller, along with a neighbor, Maurice B. Clark, formed the firm of Clark & Rockefeller, produce shippers and commission merchants, with $1000 borrowed from his temporarily flush father (with whom he maintained a relation) and a similar amount drawn from his own savings. Not for the last time, war would prove beneficial to the business interests central to this story, the onset of the Civil War causing a significant expansion of shipments through the Ohio port city, and making the timing of the fledgling firm's establishment fortuitous. Like many who could afford to do so at the time, John D. hired someone to fight for the Union in his place.

The cut and thrust of business engaged the young merchant as he knew it would and, by 1862, Clark and Rockefeller were doing so well they were invited to help finance a new refinery in Cleveland, the Excelsior Works, being erected by a recent English émigré, a day laborer turned oil industry chemist, Samuel Andrews. Clark, Andrews & Co. was formed the following year, but in 1865, Rockefeller took the helm in the operation, buying out the less venturesome Clark. Later, Henry M. Flagler, a young and recently failed salt merchant loaned another healthy stake by a wealthy uncle, Stephen V. Harkness, joined the firm, now renamed Rockefeller, Andrews and Flagler. (Flagler of course would go on to become a railroad tycoon and help develop Florida's eastern shore (he is sometimes known as the father of Miami, while the Harkness name lives on at Columbia Presbyterian Hospital's where his son, Edward S. Harkness, an active philanthropist, endowed several medical buildings.)

Owing to Rockefeller's probity, his exacting recordkeeping and rare teetotal asceticism, local bankers were inclined to lend him money. As its refinery interests and banking relations flowered, Rockefeller, Andrews and Flagler grew at a furious pace and, on Jan. 10, 1870, the partnership was disbanded. In its place a joint-stock company, the Standard Oil Company (Ohio,) was formed — John D. Rockefeller, president, his brother, William Rockefeller, the vice president and Henry Morrison Flagler, its secretary and treasurer.

By this time, Standard already controlled an enviable 10 percent of America's nascent petroleum refining trade, as well as warehouses and shipping depots, and had even undertaken to manufacture its own barrels and tank cars. But the first order of business for the fiercely competitive Rockefeller was to knock other Cleveland refiners out of business.

Rockefeller's plan was no less than a systematic effort to bring regularity and order to places where there were none, to assure steady mega-profits from what was as volatile an enterprise as man had ever known.

Standard chose as its high-speed vehicle for change the South Improvement Company (SIC.) Though it may have been the brainchild of the Pennsylvania Railroad's mighty potentate Tom Scott, it was exploited most effectively of all by the Rockefellers and Flagler, who brought unexpected ruthlessness to the venture. An alliance between the Pennsylvania, New York Central and Erie railroads, the oil country's most powerful railroads, and a couple of refiners, most notably Standard Oil, the SIC would operate under a special charter created by the suggestible Pennsylvania legislature, which had long evinced its agreeable willingness to do Scott's bidding.

In practice, the Company would dramatically raise shipping rates across the board, but by granting even huger rebates to SIC refiners, it unabashedly tilted the playing field, going so far as to pay Standard a bonus on other refiners' shipments to Cleveland (the costs of which were naturally passed on to competing refiners.) The railroads were ensured a large, steady business from Standard, while the effect, for those shippers who weren't members of the SIC, was a doubling of freight rates overnight. John T Flynn's 1941 book Men of Wealth called it "an instrument of competitive cruelty unparalleled in industry."

The ensuing outcry from competing refiners quickly forced the craven Pennsylvania legislature to yank the SIC's charter. But though its reign amounted to less than 6 weeks early in 1872, the threat the SIC scam seemed to pose, before the hue and cry grew too clamorous, enabled Rockefeller to acquire 22 of his 26 Cleveland competitors in a little over a month's time, including six in one 48-hour period. Locally, they called it the Cleveland Massacre.

As area refiner John H. Alexander stated in Ida Tarbell's landmark work The History of the Standard Oil Company, "There was a pressure brought to bear upon my mind, and upon almost all citizens of Cleveland engaged in the oil business, to the effect that unless we went into the South Improvement Company we were virtually killed as refiners; that if we did not sell out we should be crushed out.... It was said that they had a contract with railroads by which they could run us into the ground if they pleased."

Swollen coffers only fueled Rockefeller's appetite for expansion, Standard next moving to acquire interests in key New York refineries, including the city's biggest foreign exporters, while consolidating its monopoly on Cleveland refining. In 1874, Standard enticed large competitors in Pittsburgh and Philadelphia to join its orbit, and, within two years, of 22 refiners in Pittsburgh, only one remained independent. As its dominion over supply became ever more secure, Standard's ability to dictate the prices dealers might charge grew, as did its ability to demand that retailers stock its products exclusively and that producers not sell crude to remaining independent refiners. Standard excelled in this sort of strong-arm negotiation.

Each ruthless move was a considered step in Standard's pursuit of a new kind of industrial power. Using every anti-competitive trick in a book it was helping to write, Rockefeller & Co. methodically set out to achieve what was once thought impossible — a stable and predictable market in a hugely popular commodity, the sort of market that historically lent itself to gluts, droughts, wild price swings and unexpected reversals of fortune. What Rockefeller liked to refer to as "our plan," as noted in Harold F. Williamson and Arnold R. Daum's 1959 history The American Petroleum Industry, was no less than a systematic effort to dominate the oil refining industry completely, a Herculean effort to bring regularity and order to places where there were none, to assure steady mega-profits from what was as volatile an enterprise as man had ever known. In the name of success, Standard would attempt and often get away with misdeeds that no single human being could imagine, much less conscience or commit on their own without serious jail time to follow. In so doing, it would become the great granddaddy of the modern corporation.

STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURE

While Ron Chernow and other distinguished historians have documented the startlingly corrupt and illegal stunts Rockefeller and his cronies would attempt in pursuit of their ends — wholesale bribing of local, state and federal officials, for instance — many of them have gone on to conclude that Standard and its founder should not be judged too harshly, for they offered competitors fair warning of their intentions and fair terms for their properties before moving to bury them; that many who would accept the giant's offers would become wealthy as a part of the Standard family, with some, such as Charles Pratt and Henry H. Rogers of Brooklyn, even rising to positions of great authority within the organization. True or no, the heart of the matter — that such refiners really had no choice but to take Standard's terms or risk losing everything – was hardly the stuff of glowing character recommendation.

"America has the proud satisfaction of having furnished the world with the greatest, wisest, and meanest monopoly known to history."

Standard were bullies and greedy ones, at that. As the author of one survey of the young industry observed, catalogued in Williamson and Daum's The American Petroleum Industry, "Every increase in refining capacity further strengthened the firm's bargaining position in maintaining or increasing special concessions from transportation companies." Thus, each conquest would provide additional leverage with which to pressure remaining firms into selling or to face the certain destruction of their livelihoods. As the 1870s unfolded, Standard could employ its mounting domination of gathering lines, tanks cars and terminal facilities as well as its superior bargaining position with the railroads to pressure independent competitors to sell out.

Unlike many of his industrial age contemporaries, Rockefeller was not a technically knowledgeable executive, as John K. Winkler notes in his 1929 work John D.: A Portrait in Oils. "A young man who wants to succeed in business does not require chemistry or physics," he once said. "He can always hire scientists." Rather, he confined himself to finance, personnel, and administration, as well as general policy.

But what was that policy, generally? Contradicting notions of Rockefeller's fundamental decency and fairness was Standard's deceitful convention of operating through front companies and individuals whose associations with the emerging giant were hidden, denied or went undisclosed. Wherever possible, Standard bought and managed in secrecy, always revealing as little about its involvement and intentions as it could get away with. Trading surreptitiously, it had, for instance, acquired the largest refinery in Philadelphia, more than half of the refining capacity of Pittsburgh and the best known of New York independents. Through the clever use of trade groups, such as refiners' associations, as well as manipulation of the railroads and pipeline pools, (needless to say, it owned the biggest pipelines,) it was essentially able to freeze out smaller competitors at will.

Standard left a lot of bad feeling in its wake, but the real proof of its ill-gotten market power was in the pudding. By 1878, just when the public was starting to catch up to what it had amassed, Standard owned or leased over 90 percent of the total refining investments in the United States as noted by Williamson and Daum, and by 1881 production exceeded 100,000 barrels a day. Prices for kerosene dropped, pleasing consumers (and thus expanding demand,) but not as pleased as they might have been; Standard, it was now also clear, was not above selling a substandard product.

WHO NEEDS SCIENTISTS?

When it was accused by export houses of selling an under-refined and generally substandard kerosene illuminating oil, one that smoked heavily in lamps and went out easily, Standard officials huffily told them to advise customers to use better wicks. When the West of England Petroleum Association censured the company for "inexcusable carelessness" in the sale of its kerosene, Standard sent an emissary to protest and called again for the use of better wicks. Questioned more closely, they'd insist the source and composition of the oil they were then using – from Pennsylvania's high-sulfur Bradford fields – made anything else impossible. But they meant to say less profitable. A refinery fix did exist. Unfortunately for Standard's customers, the process would have lowered Standard's yield and was not adopted.

"The only trouble," explained the refreshingly frank trade paper, the Oil, Paint & Drug Reporter, "is that from a given quantity of Bradford [Pennsylvania] Oil the refined product of equal quality must be smaller than from the oils of the old fields. Those...refiners who recognize this difference...have no trouble in turning out a burning oil which satisfies the requirements of both foreign and home trade....[I]n order to prevent losses from the unreasonably low prices which they have insisted upon maintaining for the purpose of crippling 'outside' refiners, [Rockefeller and his associates] have worked the Bradford oils less than was consistent with a good quality of refined. The result has been a gummy, slow-burning oil."

Ironically, possibly as a result of high-sulfur kerosene, Rockefeller's own wife was seriously injured in a lamp explosion in November 1888, badly burning her face and hands. Though it was said at the time to be a lamp of the alcohol-burning variety, these were less widely in use by this time, and, in any event, were infrequently known to explode as this one did. Notably prone to such mishaps, however, were lamps using impure, high-sulfur kerosene.

This would not be the last time Standard chose a less wholesome product in preference to expending capital on improving its refinery practice, and, as we shall see, it would neither be the first nor last time it unfairly disparaged alcohol fuels. Just as it would work to put down its competitors in the oil trade, Standard was prepared to do whatever was necessary to keep competing fuels and gasoline additives — such as grain-based ethanol — out of sight and under siege, random badmouthing included.

The company was not only strong, but also, more importantly, demand for oil was exploding. On April 30, 1873, The Titusville Morning Herald, which had held a ringside seat for much of the boom, opined that "The production of petroleum has now become of such commercial and social importance to the world that if it were suddenly to cease no other known substance could supply its place, and such an event could not be looked upon in any other light than of a widespread calamity."

It was Standard's good fortune to have most of this market to its self. While the atrociousness of its business practices may have been clear to its competitors, it presented an appealing image of itself where it came into contact with consumers, around the world. As the historian Allan Nevins has written:

"The [foreign] stations were kept in the same beautiful order as in the United States. Everywhere the steel storage tanks, as in America, were protected from fire by proper spacing and excellent fire- fighting apparatus. Everywhere the familiar blue barrels were of the best quality. Everywhere a meticulous neatness was evident. Pumps, buckets, and tools were all clean and under constant inspection, no litter being tolerated . . . The oil itself was of the best quality. Nothing was left undone, in accordance with Rockefeller's long-standing policy, to make the Standard products and Standard ministrations, abroad as at home, attractive to the customer."

Contrary to Nevins' assumption, quality wasn't always Standard's calling card. To the contrary, from today's vantage point, we can see that the major advances in the extraction, drilling, refining and distillation of oil, including the important notion of cracking, all occurred within the young industry's first 10 years, before Standard had been assembled, and those advances were now years behind it. From this point on, further study was strangely, almost unnaturally, limited. Chemical manipulation of petroleum was hobbled by gaping holes in the scientific knowledge of the day but also by a distinct lack of interest on Standard's part in developing new processes. Having largely extinguished its competition, it had little impetus for technical and product improvements beyond those that helped to maximize its own profit.

Standard's growing monopoly position allowed it to slow down, defer and avoid entirely those useful, but potentially costly, upgrades to refineries that might have otherwise been desirable. Technological development would now slow to a crawl, though at the same time the oil giant worked overtime to limit the possibility of being caught off guard by new technological developments that might favor its competitors. To ensure upstarts and pesky independents would never cause it embarrassment, Standard systematically acquired all patents that might affect any aspect of any business it operated, and operate by its own lights only.

By the 1880s, Standard's control over basic patents and processes was so extensive that it had virtually guaranteed its participation in any and every aspect of the oil business. Its zeal for owning the newest technology, and then being able to decide, at a later date, what, if anything, to do with it, would be an important aspect of its behavior as it matured into the rapacious, dangerous (both naturally-polluting and unnecessarily super-polluting) business it would become. Rockefeller's policy of absorbing anything of technological interest, along with his fierce dedication to avoiding capital investment in refinery plant and equipment, and a disturbing readiness to savage the environment, reflected an attitude that would later commend tetraethyl lead — a new discovery made outside of its laboratories — to Standard's attention. As a product, it made the perfect emblem for Standard's vice through the ages; an outgrowth of its historic interest in monopolization, in keeping refinery investment low and its thoroughgoing disregard for the environment and the public health.

THE RISE (AND RISE) OF STANDARD OIL

In the early days, Pennsylvania was the world's only known source of oil. It seems funny today, but it was the fact and a matter of not inconsiderable significance. As Ron Chernow observed in Titan, "Had oil been found in scattered places after the Civil War, it's unlikely that even Standard Oil could have mustered the resources to control it so thoroughly. It was the confinement of oil to a desolate corner of northwest Pennsylvania that made it susceptible to monopoly control, especially with the emergence of pipelines. Pipelines unified Pennsylvania wells into a single network and ultimately permitted Standard Oil to start or stop the flow of oil with the turn of a spigot. In time, they relegated collaboration with the railroads into something of a sideshow for Rockefeller."

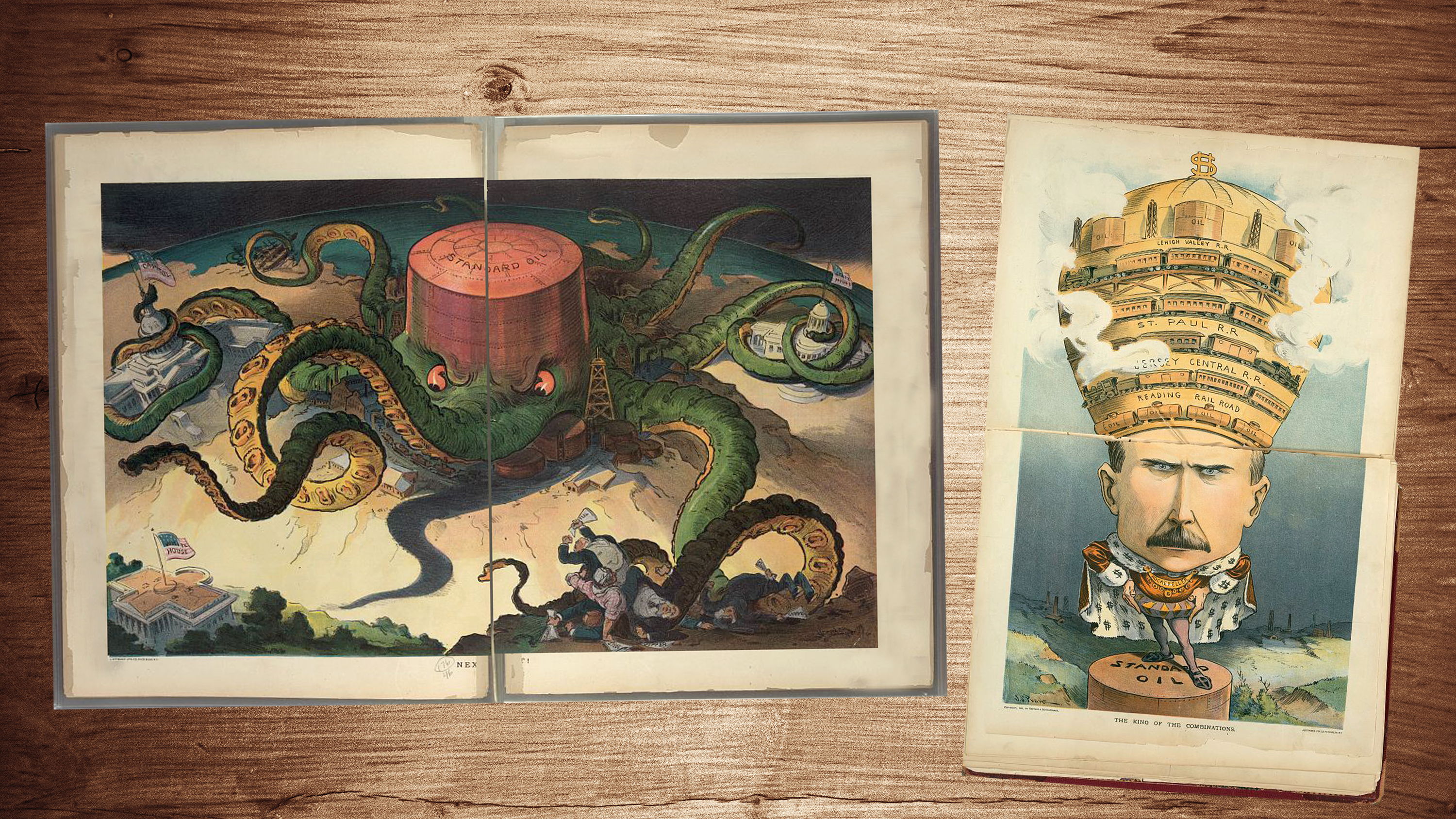

A sideshow the railroad manipulations may have been, but Standard's stranglehold on the transportation systems that competing oil producers and refiners necessarily relied on was not easily forgotten, especially as the company never relaxed its grip and kept growing in size and in scope of unspeakable deed. Sooner or later, notwithstanding Standard's best efforts to hide and disguise its ever-expanding girth, the public was going to wake up with a start to this selfish, fire-breathing monster of a corporation that stood in its midst.

Around this time, many states began their own investigations of the petroleum giant. Speaking in 1879 before a panel of the New York State Assembly established by Alonzo Barton Hepburn with the goal of shining a light on unfair railroad practices and exposing secret agreements between the roads and industry, one independent refiner described how completely the carriers had become beholden to Standard. Flowing wells meant he had oil, more than he could store, ready to ship. But the Erie Railroad had told the refiner it had no rolling stock available; its cars were in use by another company, as it transpired, a Standard subsidiary.

Commodore Vanderbilt's New York Central RR begged off, too, saying it had neither enough tankers nor terminal facilities to handle his order; Standard was using them. This left the Pennsylvania Railroad, which would happily allow an independent to hook their cars to its locomotives. Except it wouldn't charge him rates anywhere near so low as Standard enjoyed, unless the shipper could guarantee like-sized volume, an impossibility. (When Mr. Vanderbilt was questioned by the New York Committee, "I don't know," "I forget," and "I don't remember," made up 116 of his 249 responses, as The Atlantic recounted in 1881.)

Much in tune with a growing national sense of revulsion over the massive new market power being accumulated by the oil giant, Simon Sterne, counsel for the Hepburn Committee, characterized the railroad compacts with Standard "the most shameless perversion of the duties of a common carrier to private ends...in the history of the world."

The Oil, Paint & Drug Reporter, the industry trade whose heart remained (to this point) stitched to the independents, pronounced: "There never has existed in the United States a corporation as soulless, so grasping, so utterly destitute of the sense of commercial responsibility and so damaging to the commercial prosperity as is the Standard Oil Company."

And that was just their dealings with railroads. As noted, Standard dominated the pipelines, as well as the legislatures that authorized them. Conspiring with the Tidewater Pipe Line Company, the builder of Pennsylvania's main oil pipeline and a one-time competitor brought to heel with the help of the compliant Pennsylvania legislature, Standard wound up controlling 88.5 percent of the state's pipeline business, as recounted by Williamson and Daum.

While its zeal for improving its product was negligible and for minimizing its adverse environmental impact non-existent, Standard's enthusiasm for bulk shipments of oil hastened the spread of the tank car, the laying and operation of the biggest oil pipelines the world had seen, and, before long, a new era of ocean-going oil tanker.

By the mid-1880s, 70 percent of American oil was being sent abroad, making petroleum America's fourth largest export. Standard's dreams were bigger, though, as Williamson and Daum note. Rockefeller told an associate at the time, "We have the capacity to do all the home trade as well as the export, and I hope we can devise ways and means to accomplish it later on; at all events we must continue to strive for it."

Still not satisfied with its ample lot or its ambitious existing plans for growing overseas, by the early 1880s Standard had become convinced that it could make more money and possibly monopolize the world market, not only by refining oil — as it had for decades defined its narrow, albeit deep and hugely profitable brief — but also by producing it. So it set out to buy producers. Adhering to its traditions of dubious legality and optional morality, it could not help but employ its familiar mélange of front and dummy companies, price pressure and transportation muscle to force smaller firms out of business as it overran the newly discovered petroleum fields of Ohio and Indiana.

For it had become clear by now that oil permeated the earth's crust and it was but a random coincidence that Titusville was the first place from which it was vigorously extracted. Petroleum had been found in Russia, with the Rothschild and Nobel interests staking major claims, and Dutch oil prospectors in Sumatra would be granted a royal charter to line their pockets in the far East, later taking the name Royal Dutch Shell, when the firm they'd founded, Royal Dutch, merged with Shell Transport and Trading, the vehicle of crafty Londoner Marcus Samuel, in 1897.

Rockefeller – whose burgeoning wealth led to increasing accusations of his being Jewish — was moved to his own anti-Semitic outbursts when discussing Marcus, his methods, (which included use of the world's first bulk oil tankers and first passage through Suez Canal, both attempted in secrecy to avoid pre-emptive activity on Standard's part) and the affront they represented to the plans of the world's largest oil company's for global domination. Monopolizing the world oil trade had gotten harder.

In May of 1885, the bountiful fields at Lima, Ohio, were tapped by Standard with the discovery of deep reserves in Indiana close behind. However, the crude being drawn was quickly revealed as "sour" — that is, it contained a depressingly high content of the natural contaminant, sulfur. Such "skunk oil" would likely offer poor yields and lesser products after ordinary refining, and certainly sell for lower prices as crude. But Standard cornered the market anyway, buying up the local fields and stockpiling forty million barrels in storage tanks specially built, gambling that a way would be found to rid the crude of excess sulfur so as to allow its profitable sale. An opportunity for technical innovation was upon it and Standard's vast resources proved equal to the challenge.

While it set to working on ways of cleaning the sour Lima crude up, Standard was busy laboring to persuade railroads to run their locomotives on fuel oil, instead of wood or coal. It also sent armies of salesmen around to persuade other users of large coal furnaces, such as hotels, factories and other substantial institutions, to switch to oil. In many instances, more sulfurous and otherwise lesser fuel oils drawn from the heavy fractions could be passed off as adequate to the task, despite their tendencies to smoke heavily and burn unevenly.

Contemporary reports comment on the remarkable omnipresence of Standard agents and salesmen throughout the land, which worked out well for Rockefeller because his bet on the Lima fields came in big. He had taken his own advice and "hired the scientists," specifically one Herman Frasch, a consulting chemist from Germany who'd later devise a practicable method for drawing sulfur from the earth, (and whose presumably wild ways earned him the geographically inapt nickname the Wild Dutchman.) Frasch was charged with coming up with a workable process for removing sulfur from petroleum and, by 1888, he had succeeded, allowing Standard to reap major profits on its risky investment, with more to be earned shortly with the discoveries of crude in Texas, Kansas and California.

(While Herman Frash may have beeb the industry's first in-house chemist, such men of science would become widespread in the industry. During the course of the next few decades, almost every refinery would have one and Standard itself even built a research lab on the top floor of its New York City headquarters at 26 Broadway, as Chernow details. That didn't mean refiners weren't cheap, however, as refinery practice continued to ruthlessly follow the bottom line, at peril to its. Workers health and safety, as well as the general public's.)

Oil production in Ohio would soon overtake that of Pennsylvania, a development that wouldn't stop Standard from using its outsized cash reserves to acquire drilling rights to entire Pennsylvania counties. As The World would observe on June 6, 1890, "Hitherto the attention of the big Octopus has largely been directed toward crushing out all opposition in the refining of oil. This latest deal shows that it has started to crush out producers of crude oil and obtain control of their property."

By 1891, Rockefeller's Standard Oil controlled almost all of the Lima fields and by 1898 it controlled 33 percent of all American oil production, its only major competitors being the Sun Oil Co, founded 1886 by J.N. Pew, and the Pure Oil Company, a consortium of 30 independent producers founded in 1895. In 1886, Standard had entered the natural gas business, as well.

TRUST AND ANTI-TRUST

The original Standard Oil Trust Agreement was drawn up in 1882, consolidating the Rockefeller partners' many far flung enterprises and providing the basis for the formation of the Standard Oil Companies of New York and New Jersey, incorporated later in the same year. America's law of corporations was in flux (as it would be for the latter part of the 19th century) and Standard was forever taking maximum advantage of the opportunity to organize its affairs more congenially for its handful of owners.

With his customary thoroughness, Rockefeller had devised an encyclopedic stock of anticompetitive weapons. Since he had figured out every conceivable way to restrain trade, rig markets, and suppress competition, all reform-minded legislators had to do was study his career to draw up a comprehensive antitrust agenda.

The following year, Standard would begin buying land in lower Manhattan in anticipation of relocating its headquarters from Cleveland. The move to New York may have reflected the shifting geography of its holdings, the increasingly international scope of its business, a desire for more pomp or a more graphic expression of its arrival as a major player on the world financial scene, or some combination thereof. In any event, the company's new corporate offices would open on May 1, 1885, after the construction of an imposing, nine-story Renaissance Revival structure at 26 Broadway, a spot which would go on to become one of the most hallowed halls in the annals of modern capitalism. The tone inside would be hushed, and the mood as gray as the granite with which the new edifice was sheathed. Furnishings were opulent but sober, with security tight as top executives took their lunches each day on the 9th floor.

Standard Oil's empire had come together amid great secrecy in the 1870s, but it didn't take forever for the public to fathom the bulbous contours of this new monopoly, whose methods not only mimicked but also expanded on the financial chicanery and stock market sorcery of the railroad barons — by whom the citizenry already felt violated. To the new oil trust's considerable annoyance, when it attempted to quietly enjoy the fruits of its animators' beloved "plan" in the decades following their initial power grab, it encountered overt public hostility.

After a fair rhetorical bruising before the Hepburn committee in New York in 1879 came a memorably unflattering word portrait painted in the Atlantic Monthly by the progressive polemicist and pioneering muckraker Henry Demarest Lloyd in 1881. Assembling for the first time large chunks of the ugly truth, "The Story of a Great Monopoly" ran to an impressive seven printings and the London Railway News arranged to circulate free reprints to English investors. "America," Lloyd wrote, "has the proud satisfaction of having furnished the world with the greatest, wisest, and meanest monopoly known to history."

Vitriol, overstatement and occasional misstatement aside, Lloyd's prescriptive conclusion – that federal regulation of the railroads was required to curb monopolies like Standard – resonated, as it had not in the past. For its part, the always reticent Standard would appear voluntarily before another New York state committee in 1882, though it continued to remain mum on the matters of its profits, ownership, operational authority and other subjects which rightly interested investigators. It would also frequently dissemble, stymieing their inquisitors' efforts to get a handle on this thing called Standard Oil.

Paul Babcock, president of Jersey Standard wrote to Rockefeller, explaining the company's strategy shortly before being called to appear before a Congressional investigating committee, also in 1882, as R.W. and M.E. Hidynote in their 1955 work Pioneering in Big Business: History of Standard Oil Company. "I think this anti-trust fever is a craze which we should meet in a very dignified way and parry every question with answers which while truthful are evasive of bottom facts."

But the public was not won over by this strategy of evasion and bald-faced lies and, by this time, enough was known about Standard's nefarious ways for some legislative strategies to become clear.

"In a sense," Chernow has observed, "John D. Rockefeller simplified life for the authors of antitrust legislation. His career began in the infancy of the industrial boom, when the economy was still raw and unregulated. Since the rules of the game had not yet been encoded into law, Rockefeller and his fellow industrialists had forged them in the heat of combat. With his customary thoroughness, Rockefeller had devised an encyclopedic stock of anticompetitive weapons. Since he had figured out every conceivable way to restrain trade, rig markets, and suppress competition, all reform-minded legislators had to do was study his career to draw up a comprehensive antitrust agenda."

And yet it remains unclear that legislators ever really did come to grips with Standard's power.

Collusive rail rates were the first of Standard's schemes to receive remedial attention. In 1887, in no small part owing to Standard's conduct, but also to that of the powerful beef, sugar and cottonseed oil trusts, Congress passed the Interstate Commerce Act, outlawing railroad pools and rebates and establishing America's first regulatory commission. So prevalent was concern over anti-competitive corporate behaviors that seven states also enacted statutory and constitutional provisions against restraints of trade between 1887 and 1890, joining the seven who had already done so, with 20 more to follow by the turn of the 20th century, as noted in legal historian Lawrence Friedman's A History of American Law.

Officially, Standard vowed to obey the new laws, but it barely pretended, violating them flagrantly, along with many of the state antitrust laws enacted around this time. And many have reasonably doubted the depth and universality of the government's interest in battling the trusts. The laws themselves were ineffectual. As historian Stephen Skowronek summed it up, the Interstate Commerce Act was a sorry compromise piece of legislation, "a bargain in which no one interest predominated except the legislators' interest in finally getting the conflict...off their back and shifting it to a commission and the courts...."

Friedman has observed more broadly, "Public utility law in general has this nature: regulation in exchange for a sheltered market. ... Businesses [in the late 19th century] actually welcomed state control, so long as the control was not unfriendly, protected their little citadels of privilege, and guaranteed them a return on their investment." It was this growing recognition by business which caused the statute books, in Friedman's phrase, to swell around this time "like balloons, despite all the sound and fury about individualism, the free market, the glories of enterprise, Horatio Alger, and the like, from pulpit, press and bench. Every group wanted, and often got, its own exception to the supposed iron laws of trade. "

In 1890, with Standard still very much in the public's mind, the Sherman Antitrust Act was passed. Purporting to outlaw trusts and combinations in restraint of trade, it was named after its sponsor, Ohio senator John Sherman, the brother of the famous Civil War general for the Union, William Tecumseh Sherman.

It sounded fierce — "Every contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations, is declared to be illegal." But it was arguably an even shoddier piece of legislation than the Interstate Commerce Act, at least from the perspective of those who wanted to rein in the power of the trusts and their majority shareholders.

Its language, at once terse and hopelessly vague, evinced the legislators' ultimate unwillingness to deal with the matter at hand, marking it as an attempt, in legal historian Friedman's estimation, at "delegation by Congress to lower agencies, or to the executive and the courts; it passes problems along to those others." Sounds familiar, no?

In the event, the Supreme Court was, at first, unwilling to read much into the Act. As mourned Justice John Marshall Harlan's dissent in the 1895 case United States v. E.C. Knight Co., which saw the majority refusing to apply the Act to the sugar trust on what amounted to technical grounds, these great forces henceforth, were to be "governed entirely by the law of greed and selfishness.'" Later cases held out more hope, but Standard Oil would not be forced to miss a beat for some time to come. Ultimately, one could argue with genuine conviction (especially when pondering its successor, ExxonMobil, still one of the world's most profitable – and polluting — companies more than 125 years later,) that it never really has.