A Brief History Of Gasoline: How Standard Oil Got Away With It

We bust the trust here, we sue Exxon there, yet the money keeps raking in, and the pollution keeps seeping out.

The last installment of this series covered the rise of Standard Oil, the blueprint for every murderous modern corporation, but this week's entry does not cover its fall. There has been no great defeat of Standard, as the little companies that it was broken into continue to evade judgement — real judgement — for their crimes. After each blow, Standard grew a new head; at each grasp Standard, became more slippery.

This is the fifth story in a series of stories on the history of gasoline. So far, Jalopnik's tech coverage has been focused primarily on the emergence, or reemergence of the electric vehicle. One of the primary arguments levied against electric cars and electric charging infrastructure has been that bringing both into the mainstream would take significant investment from private and public actors, and that this has not generally been politically palatable in the United States. In this multi-part series (Prelude, Part One, Part Two, Part Three), award-winning journalist Jamie Kitman will lay out how American corporate and government entities have been cooperating on a vastly more costly, complex and deadly energy project for well over a century: gasoline.

THE SHOW MUST GO ON

Acknowledging that the political seas in which it was navigating its huge craft were changing, Standard had for some time in the late 19th century sought to rehabilitate its good name. This was a not inconsiderable task, for Standard's good name was never so good and its executives' tendency to make Darwinian pronouncements about the survival of their firm above all lesser comers didn't help.

Like many of the day's wealthiest business leaders, they were prone to explaining their outsized riches as proof of the involvement of the divine in their ascension to mega-riches, a claim that would not persuade all listeners. There was much work to be done changing the public's perception, although there was no question of the firm changing its stripes. It wouldn't. As the historian Allan Nevins observed in his 1953 biography of Standard's founder, John D. Rockefeller was one of the most self-righteous executives in all of American corporate history, which is saying something.

While the trust's strategies in the coming century's corporate public relations battles would come to number many, its instinctive response to PR worries was often silence. Early on, it had also adopted the time-honored expedient of purchasing the goodwill of possible critics, beginning with the trade papers covering the industry. In 1881, Ohio Standard lent money to the manager of the Oil City Derrick. Four years later, he sold it to a publisher who was friends with Standard executives. The Oil, Paint & Drug Reporter, long a thorn in Standard's side, also struck a considerably more respectful note after it merged in 1883 with yet another journal financed by Standard.

Standard would then hire its first public relations specialists. Come the 1890s, the Jennings Advertising Agency would endeavor to place favorable notices on its behalf in newspapers in Ohio and western Pennsylvania. In a not untypical practice for the time, publishers would collect three cents from the agency for every supplied line they printed in the way of straight news or reader interest items. Previously, Standard had worked to achieve the same effect by subsidizing or extending loans to newspapers and periodicals.

Rockefeller also might have hoped that his increasing charitable giving would soften his image. A mean-hearted tyrant in the business realm, he'd begun, increasingly, to delegate authority to underlings and committees, as he devoted more of his own attention to philanthropy.

As his wealth and name recognition grew, Rockefeller often found himself being hit up for money, stacks of entreaties (by turns, pitiful, heartfelt, insincere, criminal) arriving by mail each day. But he'd grow to prefer a more systematic form of giving. In the 1880s, he'd give generously to support Spelman College, the former Atlanta Baptist Female Seminary, an institution of higher learning serving primarily Black women and renamed after his in-laws, leading abolitionists of the day. In 1890, Rockefeller helped to found the University of Chicago, which quickly became a leading university, in no small part owing to $80 million he'd funnel its way. In 1891, Rockefeller would hire Frederick T. Gates, a Baptist minister who caught his attention, to oversee his benefacting. Gates' piety, like Rockefeller's, did not dull what turned out to be a rabid business sense, and this Rockefeller admired greatly about him, the capitalist theologian. Gates, as he recalls in his autobiography, worked to introduce to this charitable realm what he called "the principle of scientific giving," moving his boss' charitable work from "retail giving" to the safe and more pleasurable realm of "wholesale philanthropy."

Some biographers have said Rockefeller's involvement in the charitable sphere was marked by the same focus, orderly habits and attention to detail that marked his for-profit enterprises. Yet despite many worthy deeds and some unmistakable glimmers of progressive ideology on some of the important issues of his day, Rockefeller's Standard, envied by many and enthralling more, often as not played the role of a villain on the American stage, a sad but undeniable fact of life.

By the close of 1891, the Standard Oil Trust held equity stakes in an eye-popping 92 separate companies. A steady stream of government hearings and investigations would bring glimpses of the essential nature of this massive combine to the public's attention, along with vivid tales of thuggish, anti-competitive activity that had gone on openly in Standard's name or, secretly, on its behalf.

Such hearings shed light on the trust's ruthless ways and almost paranoiac secrecy vis-à-vis the public and its elected representatives regarding basic issues concerning Standard's organization, income, and profit.

If fathoming the complexity of Standard's business was daunting, consider that in 1893, Rockefeller received an executive summary from his office telling him that in addition to controlling the world's largest oil company, some natural gas ventures and several homes, he personally also held interests in 16 railroads, nine mining companies, paper, nails, soda and timber, nine banks and investment companies, nine real estate companies, six steamship lines and a couple of orange groves.

Given that the first part of philanthropy is having the money to give away, Rev. Gates' financial acumen would often be summoned for his boss' business purposes outside the spiritual realm.

Like the view through a keyhole, government investigations of the day afforded but a limited view of Standard's complex world. But one got the gist. Here was a singularly self-aggrandizing outfit with few scruples attempting, more or less successfully, to control the market in a wildly popular commodity that somehow permitted it to hold the world by its shorthairs, which it has ever since.

There was, as the century drew to a close, a deep and depressing sense that there was naught that could be done at law. The corporate genie was out of the bottle. John D. Rockefeller and seven other original trustees, along with nine other Standard executives, held more than half of the trust's certificates of ownership and Rockefeller half of these. Shareholders were more numerous and diverse in raw numbers, but, besides Rockefeller, who'd retire from the day-to-day affairs of the corporation in 1897, while maintaining his control, the Standard Oil combine answered only to the Pratt and Harkness-Flagler families, along with blue-bloods named Vanderbilt and Payne-Whitney.

From the first barrels of oil shipped out of Drake's well, to the turn of the 20th Century, when more than 60 million barrels of oil would be extracted in America, Standard had sold the vast majority. Its owners were unimaginably rich and they weren't going anywhere.

Ironically, those in the oil industry would occasionally be gripped by the fear that their great source of wealth would dry up, that oil would run out. At one meeting in the 1880s, as Ron Chernow notes in Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr., the Standard board even pondered the wisdom of selling out of the oil business entirely and transferring its capital to a safer business.

There was, too, the fear that, even if the supplies lasted, the market might dry up or shrink. Though per capita British use of kerosene trebled between 1884 and 1894, kerosene use in America (and elsewhere) was beginning to flatten with the rise of electricity and increased use of natural gas. With a declining demand for naptha (an intermediate fraction of petroleum, often used as a solvent,) Standard's marketing departments would hurriedly attempt to encourage the use of gasoline in stoves, sending salesmen out into the field to instruct customers on correct usage and leaning heavily on insurance companies to rate them favorably.

(Ironically, as we noted in our last installment, John D's wife was injured in a lamp explosion in November, 1888, badly burning her face and hands. It is said to be an alcohol lamp, but these are not known for exploding. Lamps using impure kerosene, however, are.)

Happily for the Standard interests, by the late 1890s its marketing efforts had paid off; fuel oil was in vogue as a replacement for coal and Standard had the American market in this increasingly important product all but locked up. Profits from kerosene sales overseas continued to roll in, too, served up by its wholly-owned English subsidiary, Anglo-American Petroleum Company (established in 1888;) a German one, Deutsch-Amerikanische Petroleum-Gessellschaft, or DAPG (1890;) and, from Holland, where the American Petroleum Company (1891) did its bidding. Standard affiliates in Italy, Denmark, Switzerland, France and Spain further padded its accounts.

Though stiff competition in European markets from the Russian oil kings, the Nobels and the Rothschilds, rankled for decades, causing years of severe price-cutting and profit foregone, with the exception of Peru, Standard would be the sole supplier of oil in Latin America in the 1890s and it controlled much of the Canadian market through the acquisition of the Imperial Oil Company. In the Far East and in Africa, Standard would face its toughest competitor, Royal Dutch Shell.

Back at home, tempered only by the success of isolated independents selling specialized lubricants and paraffin wax, Standard's share of the total market for refined products — estimated by a company official in 1898 — stood at a robust 83.7 percent. With its omnipresent blue barrels and shiny tank wagons, Standard was an early exercise in corporate branding and while many might have despised them for their unethical conduct and gouging ways, they were nevertheless working to be seen — and largely were so perceived — as competent suppliers of a hygienic and carefully-prepared product. However distantly that mirrored the actual truth, Standard wisely appreciated that what happened behind closed doors mattered less to the public than a comforting image of consistency and purity.

Clearly, no one has yet cured Standard of New Jersey's successor, Exxon Mobil, of what is wrong with it.

Beyond that, the near-term outlook for oil supply was bright, after all. As the 19th century drew to its conclusion, oil would be discovered near Los Angeles and elsewhere in California, eclipsing the Pennsylvania and Ohio production that once seemed so formidable.

With the electrification of world gathering speed in the late 19th century, there was some doubt cast on demand, as petroleum-based illuminants would surely come to be supplanted by electric light and the use of oil to generate electricity was not yet a foregone conclusion. Thus, the arrival of the first internal-combustion-engine (ICE) cars also around this time, must have seemed heaven-sent. Gottlieb Daimler's first effort made its debut in early 1880s, and Karl Benz's three-wheeled Patent Motor Wagen broke cover in 1886. The American Duryea Bros. built their first car in 1892 and, soon afterward, Henry Ford would construct his first horseless carriage. The automotive age was underway.

The gasoline age was not a given, though. It was far from certain, at the start, that gasoline would be the fuel the automotive pioneers would use in their new inventions. Ford, for instance, would often speak in favor of plant-based ethanol as a power fuel and Rudolf Diesel demonstrated his new compression "diesel" engine at Paris's Exposition Universalle in 1900 powered by peanut oil. Standard and its extensive network of salesmen and distributors made it their business to promote the petroleum-based option known as gasoline, and later diesel. Almost miraculously, it seems in retrospect, Standard Oil salesmen were physically present when Ford debuted his first car, and when the Wright Bros. achieved their historic airplane liftoff in Kitty Hawk in December 1903, running gasoline in its crude air-cooled motor. But the salesmen were everywhere. Around this same time, the British Navy was persuaded to begin using oil in its battleships, a decision which would cause the U.S. Navy to revisit its longstanding anti-petroleum policies.

STANDARD HOLDING

In 1889, the debt-ridden State of New Jersey, casting about for ways to generate revenue, changed its laws governing corporations, for the first time enabling these newly powerful legal entities — chartered historically by the various states with extremely narrow remits in terms of what businesses they were permitted to engage in and where — to hold stock in other corporations. Developments along this jurisprudential line would lead numerous companies to incorporate in New Jersey post haste, generating revenue for the state, at the price of throwing the floodgates for corporate expansion wide open. (Delaware, home of the DuPont interests, would soon follow New Jersey's lead, arranging for laws of corporate governance even more favorable to the new corporations and would soon become the preferred haven.)

Recognizing the glorious sound of opportunity knocking, the Rockefeller interests pounced, forming Standard Oil of New Jersey to buy other Standard companies outright, or merely large, controlling blocks of their stock. Functioning both as an operating and holding company, it allowed Standard's seventeen primary shareholders to now more easily exercise their will, electing directors for the 20-plus companies now combined, and calling shots from the top down, with less of the wink-winking and subterfuge their previous arrangements had required.

The following year, the Sherman Anti-Trust Act was passed by a 51-1 vote in the Senate and by unanimous vote of the House of Representatives, then signed into law by President Benjamin Harrison. Despite this and the clear anti-competitive tenor of Standard's modus operandi, federal attorney generals weren't much for applying the provisions of the new Act to it. Only a few states would rise to the challenge of bringing action against the Standard trust. On March 2, 1892, however, one of them did — Ohio. Perhaps not coincidentally, the state that knew Standard best seemed to like it least.

(Read more about Standard's exploitation of Ohio's bountiful "skunk oil" in our previous installment in this series here.)

The Ohio Supreme Court concurred and ordered the Trust dissolved, based on its finding that Standard Oil of Ohio was being controlled not by its Ohio directors, but from the executive offices at 26 Broadway, in violation of its state charter.

Responding to the court's ruling, on March 10, Standard Oil voluntarily dissolved the trust. In a lightning round reshuffle, it invited shareholders to exchange their trust certificates for individual shares in the 20 constituent companies it owned. The Standard Oil companies of Ohio, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky and California, the Atlantic Refining Co., Waters-Pierce Oil Co., the Continental Oil Co. and others passed to holders of Standard shares.

But, five years later, Standard had yet to redeem some $27 million in smaller shareholders trust certificates. On November 9, 1897, its Standard Oil of Ohio property was accused by Ohio's attorney general of having never intended to leave the trust and then cited for contempt of court. The following year, with litigation still ongoing, Standard Ohio was charged with burning records to destroy evidence of past Rockefeller skullduggery and later with attempting to bribe the state's attorney general, a not implausible accusation given Standard's decades of unholy relations with elected officialdom.

Notwithstanding the birth of anti-trust laws and enforcement actions, such as Ohio's case against Standard (which ultimately failed,) trusts and mega-corporations flowered wildly in this period, with 198 formed in the four-year period, 1898 to 1902. In June of 1899, when New Jersey again amended its incorporation laws, Standard would move to avail itself of their liberal new provisions, becoming a pure holding company, with the parent, Standard Oil of New Jersey, now controlling nineteen large and twenty-two smaller companies.

The lesson was again clear: The great body of American law would not stand in the way of corporate giant-ism; it would play catch up.

THE HISTORY OF THE STANDARD OIL COMPANY

And so Standard rolled on. When the International Geodetic Association announced plans to measure the earth, the World joshed that the information would finally "enable the Standard Oil Trust and other trusts to learn the exact size of their properties."

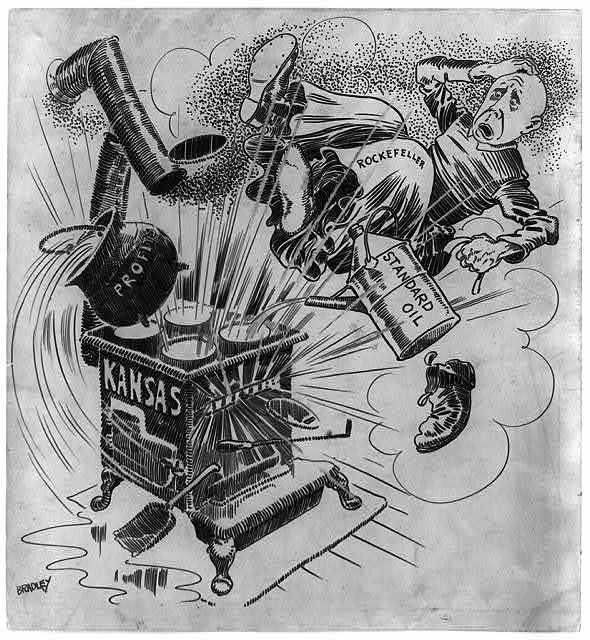

The combined efforts of the federal government and numerous states to curb the growth and continued excesses of the country's biggest trust had proven woefully inadequate, and it again fell to muckraking journalists to give voice to the nation's simmering antipathy towards this new, concentrated power. Most influential was Ida Minerva Tarbell's "History of the Standard Oil Company," which appeared serially in McClure's, the era's leading journal of responsible (i.e, middle class,) progressive thought, starting in 1902 and running through 18 installments before its compilation and publication as a book in 1904.

McClure's had wanted to profile a trust and, it asked, why not "the first in the field?" Standard had "furnished the methods, the charter, and the traditions for its followers. It is the most perfectly developed trust in existence; that is, it satisfies most nearly the trust ideal of entire control of the commodity in which it deals. Its vast profits have led its officers into various allied interests, such as railroads, shipping, gas, copper, iron, steel, as well as into banks and trust companies, and to acquiring and solidifying of these interests it has applied the methods used in building up the Oil Trust. It has led in the struggle against legislation directed against combinations. Its power in the state and Federal government, in the press, in the college, in the pulpit, is generally recognized."

"We will see Standard Oil in hell before we will let any set of men tell us how to run our business."

Tarbell's work profited enormously from the unlikely (bordering on bizarre) contribution of a key senior Standard executive, Henry H. Rogers. Born in humble circumstances, Rogers had worked his way up from the oil fields of Pennsylvania to a partnership with Brooklyn refiner Charles Pratt, whose company would be bought by Standard Oil in the 1870s. Rogers would later become, with Rockefeller and his brother William, one of the three horsemen of the Standard Trust of 1882 and a very rich man. For reasons not well understood, Rogers gave Tarbell numerous interviews beginning in 1902, after their introduction was brokered through a mutual friend, the great American man of letters, Mark Twain.

(Rogers, was a friend and benefactor of Twain, an unlikely one given the writer's historic antipathy to big business. The Standard executive worked long hours to bail Twain out of financial difficulties, loaning him money and arranging terms with his creditors after yet another of his many failed, pie-in-the-sky business schemes tanked, threatening to bankrupt the writer. One can only wonder if Rogers' largesse had any effect on the high regard in which the Twain held Standard Oil in his dotage.)

Though he still very much worked at 26 Broadway and professed to love his job, Rogers dished dirt by the carload, in what can only have been one-part therapeutic confessional and one-part long overdue venting of subterranean resentment toward Standard, the company he'd been menaced by back in his days in Pennsylvania or, later, as a partner in Pratt's independent Brooklyn refinery.

While doubting the morality of the whole enterprise, Tarbell accepts as true Rogers' rosy, latter-day view of Standard, shaped perhaps by the substantial wealth that accompanied his association with the bigger firm and such as eased his transition into becoming a Standard man.

Rogers sang of the virtues, efficiencies and engineering wonders Standard had brought forth and Tarbell's history accepts as incontrovertible truth this part of his story. Nonetheless, she closes with the admonition, hopeful to the point of being hopeless, "We, the people of the United States, and nobody else, must cure whatever is wrong in the industrial situation." Writing today, more than one hundred years later, there remains disagreement as to whether that sort of thing — curing the industrial situation — falls into the American public's job description, or ever did. Clearly, no one has yet cured Standard of New Jersey's successor, Exxon Mobil, of what is wrong with it.

Standard's failure to rebut Tarbell's manifesto at the time of its publication seems curious by today's light, as does Rogers' role in her creation of it. There was value for the corporation in her affirmation of its technical prowess, its rationality and efficiency. Yet, when it came to the tales of state houses bought and sold, and the congenital dishonesty on display as Standard assembled its empire, none of the denials, refutations, explanations or lawsuits one might have expected to issue from 26 Broadway ever came. The corporation was stony silent.

In years to come, it would come to view its quietude in the face of such skewering as mistaken, since disinformation always beats the unvarnished truth. Yet not long after, in the 1920s, Standard would again be guilty of a similarly odd and inappropriate silence, when asked to respond to news of a fatal industrial accident at one of its plants in the early days of leaded gasoline. An early and enthusiastic participant in the first golden era of advertising and strategic public relations, Standard would once again freeze in the headlights. But to be fair, Standard Oil was connected enough, strong enough and rich enough to weather anything, including its own PR mistakes.

STANDARD FLIES SOLO

John D. Rockefeller would keep the title of president and remained the supreme commander of the Standard ship, but as charitable activities engaged more and more of his time in the 1880s he began handing over the operational reins to his trusted vice president, John Dustin Archbold. Standard Oil's day-to-day John D., its man on the bridge as it entered the 20th Century, would be Archbold, another one-time Standard competitor who'd learned to see and do things the Rockefeller way — fast, loose, but orderly and methodical, and always steeped in self-righteous fantasy, and thus further tapped the corporation's perpetual inclination to play dirty. In the collective hallucination of Standard's leaders, their ends were so great and noble, their venture's success so clearly the fruit of heavenly inspiration, that they justified any means, however unseemly, including the routine bribery of public officials, the ruining of men's lives and livelihoods, as well as interstate chicanery of every description, legal and otherwise.

Like his boss, Archbold made ready reference to the compendium of anti-competitive business practices and cross-border deceptions that his one-time nemesis, Rockefeller, had collected and used against him in Pennsylvania, back in Archbold's early years as an independent refiner and vocal critic of Standard Oil. With time and hard experience, he resolved to follow the old maxim, if you can't beat them, join them and also became a model Rockefeller employee.

Focus and bloodthirstiness would lead Archbold to the top, but bad publicity would follow executive and oil company forevermore. But then so, too, would dozens then hundreds of consecutive quarters of record profits and the immense fortunes they created.

Hauled before a New York State investigating committee in 1888 and questioned closely, Archbold was already expressing that rare combination of feisty defiance coupled with profound memory loss that had led him within a heartbeat of the chief executive's office. His testimony, as described by one observer, was "evasive, insolent and hot-tempered."

The pay was great at the top but the ride was bumpy; the new century rolled in on a wave of mixed news and bad reviews for Standard. This did little to steady the nerves of another John D., John D. Rockefeller, Jr., one of John D.' Sr.'s four children and the billionaire's only son, the one offspring who would actively participate in the company's affairs.

Junior had no sooner joined the firm in 1899 than Standard managed to get itself kicked out of Texas in 1900; a semi-secret marketing subsidiary it founded was convicted of violating antitrust laws, leaving new competitors Gulf and Texaco to thrive as Texan gushers came in by the day. (Imagine ExxonMobil getting shot down trying to do anything in Texas today. What are the odds of that?) With still more oil struck in California, Oklahoma (or the Indian Territories, as they were then known,) Kansas, and Illinois, and demand exploding, there were ready profits to be made, but total control had suddenly become too much for Standard.

The complete monopolization of the world petroleum market was also a bridge too far. Productive Russian fields might, in a given year, surpass United States' output, while Royal Dutch Shell continued to develop East Asia's vast markets and fields for itself. Any hopes for a worldwide monopoly had to fade away, leaving only hopes for an orderly cartel arrangement, in which the world's old business was split up in a harmonious and lucrative way between its biggest players. Not that any of this meant Standard was throttling back plans for world domination, just that the realization that there were certain limits had dawned.

A presumptive fast tracker in Standard's executive ranks, Junior had been groomed for better things, and ascended quickly to a vice presidency. But he would be badly hobbled by guilt, anguished at evidence he'd come across of systemic corruption in the business his father built, particularly the bribes and political payoffs that were the lifeblood of Standard's legislative program. The psychic burden appears to have been crushing.

Against this, could only have been his crippling sense of obligation. On July 23, 1899, only days after Junior began commuting downtown to work at Standard's headquarters at 26 Broadway, his mother, Cettie, wrote him, neatly encapsulating (and fairly radiating) certain messianic tendencies of the Rockefeller clan (shared with many other wealthy families of the day,) as she declaimed on the nature of his responsibility. "You can never forget that you are a prince, the Son of the King of kings, and so you can never do what will dishonor your Father or be disloyal to the King."

As often seems the case for those raised in the shadow of great wealth and power, as well as for those whose mothers compare them to the Christ child (and why not?,) Junior was a sensitive sort.

He was, like his father, a teetotaler, a devout Baptist and bible student, the only difference was, he had a weak stomach, preferring not to think about how Standard became Standard, or what keeping it that way meant. The sordid history recounted by Tarbell tended to drive him away from the business that would nonetheless always define his life. Indeed, in the immediate wake of her book's release, Junior found it necessary to take a year's absence from his duties, having been laid low by migraines, insomnia and, eventually, what we might today call a nervous breakdown. He'd later become a director of Standard but the Johns D. (Archbold and Rockefeller, Sr.) would continue to set the tone.

Given time, though, Junior would get the hang of it, playing an unfortunate role in the 1914 Ludlow Massacre, the violent, Standard-funded response to the workers strike for union recognition at its Colorado Fuel and Iron Company. On John D. Jr.'s watch, company militiamen set a tent ablaze, killing two women and 11 children, and casting Junior in the exact light he'd hoped to avoid in life. Pickets joined by Upton Sinclair and Emma Goldman would protest the deaths in front of Standard's corporate offices at 26 Broadway.

WE TRUST IN ANTI-TRUST

Tarbell's book did more than knock Junior out of his intended orbit; it re-energized those in government who mistrusted Standard, its conduct and motives. Things were afoot in the land and in Washington, D.C., worrisome things if you were Standard Oil, and they did not go unnoticed.

Embracing the timeless dictum "always side with a winner," Standard Oil men began donating generously to incumbent Teddy Roosevelt's first campaign for the presidency in 1904. (While Vice President, Roosevelt had assumed the office following the assassination of William McKinley in 1901.)

Years later, in 1912, Archbold was summoned to testify before a congressional committee investigating political contributions to the Republican Party and claimed that Theodore Roosevelt knew full well of Standard's $125,000 contribution before the 1904 campaign. Roosevelt denied it point blank, lifting the stench from his campaign when he produced copies of letters written in the day ordering his campaign managers to return any Standard money, should it be received.

When TR won the 1904 term by a wide margin, old man Rockefeller sent his president a telegram. "I congratulate you most heartily on the grand result of yesterday's election." It was an uneasy union, at the best of times. Roosevelt represented the progressive wing of the Republican Party, which was anti-trusts, as a rule, and suspiciously solicitous of the workingman. For its part, Standard had only just broken the 1903 strike for union recognition at its frighteningly medieval 1300-acre Bayway plant in Linden, New Jersey, a toxic waste dump of an old (1877) oil depot turned refinery (in 1909,) which remained in operation until 1993.

As Michigan would become the automobile state, New Jersey became the gasoline state and the Bayway, a star of the lead gasoline story, one of its great emblems.

A petrochemical carbuncle by the lovely spot where today Routes 278 and I-95, the New Jersey Turnpike, come together, at the Turnpike's Exit 13, the Bayway plant is one of the oldest and most polluted spots on the planet. In this capacity, it was the subject of a 1991 court order, ordering the site's remediation along with cleanup at a related and similarly venerable Jersey facility in nearby Bayonne, fully interconnected with the Bayway plant by pipeline (leaky, of course,) until 1972.

The court's order arose from the finding by the state of New Jersey that Standard and its successor ExxonMobil had comprehensively contaminated the surrounding environment, including soil and groundwater, while refining, receiving, storing and shipping crude and partially refined oil, as well as numerous petroleum products and petrochemicals it manufactured, leading to soil and groundwater contamination with several hazardous substances, including benzene, lead and other petroleum components, all of which have also been found in the surface water, wetlands and sediments to which the facilities are adjacent.

Like labor unions, Standard's attitude towards governments it didn't own and government regulation it didn't write was unbending and eternal — it hated them. As journalist John T. Flynn notes in God's Gold, their view was summed up best and for all time by Henry H. Rogers when he said, "We will see Standard Oil in hell before we will let any set of men tell us how to run our business."

The pith and candor may not be so acute anymore, but Rogers' remark describes the way the company continues to feel and behave to this day. And it's worth underscoring in this connection how, in service of this overarching principle, "No one tells us how to run our business," Standard and its successor have done a wonderful job throughout the years, keeping the world's political and regulatory entities regularly updated on the fact that it is the oil company running the show, not them.

In 2004, for instance, the State of New Jersey sued ExxonMobil again, "after being unable to reach agreement with the firm as to what constituted adequate restoration of the Linden and Bayonne sites to 'pre-discharge' condition, and what was adequate compensation to the State for its lost natural resources" relative to the 1991 court order and the state's earlier finding. By this time, however, ConocoPhillips owned the refinery.

Classic Standard Oil — they committed the act, then worked to prevent the truth emerging for the longest time, then fought its punishment in court and, after all that time, money and effort, refused to pay its penalty, in this case, cleaning up what it had wrought, litigating and litigating. Reminding one of the Exxon Valdez judgment, which ExxonMobil refused to pay for more than a decade, fighting until the Supreme Court in 2008 reduced punitive damages ExxonMobil had been ordered in 1994 by a lower court to pay by roughly 80 percent, from $2.5 billion (two days of oil revenue for it, at the time) to, thanks to the highest court in the land, $504 million. (This followed successive lower court reductions to $4.5 and $2.5 billion.) Following the judgment, Standard's shares fell briefly, by less than one percent.

So no surprise then that it now appears that Standard has largely gotten away with nearly a century and a quarter of polluting at Bayway, all but unchecked and unrestrained. Imagine the Bayway and Exxon Valdez sins multiplied over decades and in a multitude of sites and you will comprehend the massive scope of the potential liability should this corporate person, today known as ExxonMobil, were ever to be held accountable for its pollution. And that is even before you read about lead gasoline or the multitudinous others toxic gasoline additives and by-products in which they were immersed. No wonder they like to talk about so-called tort reform.

Like they say, no one tells them what to do.

TRUSTBUSTER THRUST

It is, however, always darkest before the dawn and so it was for Standard.

The year 1905 found Albert Einstein first proposing his theory of relativity, and the senior John D. Rockefeller on the lam, embedded at his Lakewood, NJ, compound, attempting to duck process servers in the first of several lawsuits brought by states' attorneys general from around the country.

The tide of good fortune seemed to be going out for Standard. Around the time a warrant was issued in Ohio for his arrest, Rockefeller began to reconsider his aversion to media attention and hired his first publicist. In 1906, Teddy Roosevelt signed the Pure Food and Drug Act into law along with another key piece of legislation widely considered anti-business at the time, the Hepburn Act, which granted broader rights to the Interstate Commerce Commission and brought railroad freight and interstate pipelines to heel. Using Standard Oil as a bugaboo to galvanize public support for legislation, privately, Roosevelt would leave Standard guessing where he really stood. They weren't much liking the direction things were headed, though.

By summer 1907, legal proceedings against the oil trust were underway in seven federal courthouses and in the halls of justice of six states (Texas, Minnesota, Missouri, Tennessee, Ohio and Mississippi). An Ohio grand jury brought 939 indictments against Rockefeller and Standard officers. Pretty, pretty busted.

But Standard was a visionary artist working in a bold new medium, multinational corporate oligarchy, and, like other epochal transgressors of societal mores, it offended many as it painted a giant rainbow mural of anti-competitive practices, from illegal rebates to corporate spying, from bogus subsidiaries, stock gaming and other acts of deception to predatory pricing policies and on. Many didn't like or appreciate Standard's modus operandi, but there really wasn't much they could do about it.

In a railroad rebate case coming out of Chicago, Judge Kennesaw "Mountain" Landis (later baseball commissioner during the famous Black Sox series-fixing case) got so worked up at Standard he levied a whopping $29.24 million fine against the company, the largest in American history.

The whopping verdict was thrown out on appeal, but Roosevelt wasn't giving up so soon and came back at the trust again. In 1909, another suit was brought by the Justice Department, this time extending to 444 witnesses, 11 million words of testimony, 1,374 exhibits, and 12,000 pages of proceedings in 21 volumes. If Standard wasn't beleaguered enough, by this time 21 state antitrust suits against it were also pending simultaneously.

Keeping anti-Standard sentiment at the forefront of the public agenda were the newspapers of William Randolph Hearst and the newspaper publisher (and sometimes political candidate) himself. Speaking at a public appearance in Columbus, Ohio, in 1908, he'd kicked off an anti-Standard campaign by reading aloud a series of purloined letters penned by Standard vice president Archbold. Making them noteworthy was the fact that each had once accompanied a bribe payment to a well-known politician. Hearst, a onetime congressman whose presidential aspirations were no secret, had gotten hold of the Archold letters some years earlier, but found it useful to wait till now to lead his charge against America's largest oil company.

In November 1909, a federal circuit court in St. Louis unanimously ruled that Standard Oil of New Jersey and its thirty-seven affiliates collectively violated the Sherman Antitrust Act. The holding company was given thirty days to divest itself of its subsidiaries.

Standard appealed immediately to Supreme Court, and that day began a long wait that lasted until May 15, 1911, when the Court came back and upheld the lower court's order to dismantle Standard, giving it six months to spin off 30 subsidiaries, including Standard Oil Company of New York, the Standard Oil Company of Ohio, the Standard Oil Company of California and the Anglo-American Oil Company.

Sounds major. And it was on paper, though in the end it was hardly the huge victory for the people some might have hoped for, or the crushing blow to the Rockefeller interests for which others might have prayed. Prices didn't fall, refineries and petroleum products didn't become better or more wholesome and the element of punishment was nowhere to be seen.

There was no need for Standard to be remorseful, downcast or to regret any of its conduct or even the result, as shares in the individual companies the Standard fathers now held didn't fall. Rather, they soared, making their holders even richer. (To give one example, a share of Standard of Indiana worth $3,500 in 1912 was worth $9,500 at the beginning of 1913.) In 1913, Rockefeller's net worth climbed to $900 million, or almost $25 billion dollars in 2021 dollars. Particularly profitable was Jersey Standard, the largest piece of the dissolved lot, by virtue of comprising, too, the Standard Oil Company of Louisiana, the Carter Oil Company and the Imperial Oil Company, Ltd., of Canada. Emerging from the dissolution, Standard of Jersey held properties worth more than four times those of any other separated company, as detailed in the biography of the company's president Teagle of Jersey Standard. No wonder it would go on to become so big.

As Teddy Roosevelt remarked with no little irony in 1912 (recounted in Daniel Yergin's Pulitzer Prize-winning history The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power), the impact of the Court's decision already had become clear. "No wonder Wall Street's prayer now is: 'Oh Merciful Providence, give us another dissolution.'"

"Oil continued to move from well to market through exactly the same channels as before, simply because there were no other channels. The solemn words of the United States Supreme Court Chief Justice had not changed the location of a single refinery or pipeline or marketing station."

Somehow, after all that litigating and anti-trusting, Standard had managed to wind up doing all right for itself, extraordinarily well even. The owners remained the owners and the companies they owned changed not a whit: Standard Oil of New Jersey, (home of the Esso brand, later known as Exxon,) Standard Oil of New York (later Mobil,) Standard Oil of Indiana (Amoco,) Standard Oil of California (Chevron,) Atlantic Refining (ARCO and later, Sun), Continental Oil, (once a part of DuPont and today ConocoPhillips,) and Chesebrough-Ponds, which began as an independent maker of petroleum jelly, before being bought by Standard, forged ahead. Standard Oil of Ohio (SOHIO) lived on, too, many years later becoming part of BP. Each of the "new" firms accepted their role in what came to be the new, unspoken Standard alliance, and their brands soldiered on as they swiftly divided the country into non-compete territories and markets that near as identically mirrored their pre-dissolution divisions. The coming boom market in gasoline looked inevitable and cooperation promised excellent returns for all.

For his part, Roosevelt had no doubt that Standard and its owners had escaped punishment richly deserved. Not all combinations restrain trade and require breaking up, he wrote in his 1913 autobiography. " Such action is harsh and mischievous if the corporation is guilty of nothing except its size." But "where, as in the case of the Standard Oil, ... the corporation has been guilty of immoral and anti-social practices, there is need for far more drastic and thoroughgoing action than any that has been taken, under the recent decree of the Supreme Court.

"...Not only should any huge corporation which has gained its position by unfair methods, and by interference with the rights of others, by demoralizing and corrupt practices, in short, by sheer baseness and wrong-doing, be broken up, but it should be made the business of some administrative governmental body, by constant supervision, to see that it does not come together again, save under such strict control as shall insure the community against all repetition of the bad conduct—and it should never be permitted thus to assemble its parts as long as these parts are under the control of the original offenders, for actual experience has shown that these men are, from the standpoint of the people at large, unfit to be trusted with the power implied in the management of a large corporation."

Strong words, but Roosevelt knew of whence he spoke. For he had identified the key problem — more than forty years of irrefutable history by 1911 said the Standard Oil company was unfit to be trusted. And yet nothing was being done to punish it or the people who animated this fictional corporate person and helped it to commit outlandish deeds that they as individual, non-fiction persons might not have dreamed up and wouldn't have gotten away with for a moment, if they had. It was the same for their successors, including Walter Teagle, who led the company when it first added lead to gasoline. Unlike petroleum, which can be endlessly rearranged and re-jiggered to suit different purposes, Standard Oil's essence was unreformable, rendering it the once, present and always baddest of corporate bad boys. And its work had just begun.

THE GASOLINE AGE

By 1910, gasoline sales had steamed past the sales of kerosene and illuminating oil combined, making it clear that the world had changed and the petroleum business along with it (or, one might wonder, was it the other way around?) Two years earlier, a pair of wildly successful automobile ventures, the General Motors Corporation and Ford's Model T automobile, had been launched, and together, their success was predictive of much of the next hundred years of American history, which, as we know, would be the best of times for purveyors of gasoline. From a handful to a few hundred to a few thousand, the number of autos owned by Americans would climb exponentially in the new century, hitting 2.5 million units by 1915, and 9.2 million by 1920.

As demand for gasoline grew, refiners desperately sought higher yields of gasoline from any given quantity of petroleum. For some time, this depended largely on the nature of the petroleum being drawn from the earth. Then in 1913, the Standard interests were blessed when Robert E. Humphreys, chief chemist in charge of Standard Oil of Indiana's Whiting refinery laboratory, came up with the process for thermal cracking of oil, increasing the yield of gasoline from crude by the use of heat and pressure.

As is so often the way, it was Dr. William M. Burton, Indiana Standard's general manager for manufacturing at the time, for whom Humphreys' discovery, the Burton distillation unit, was named. It was an invention that did wonders for Indiana Standard's business and it didn't hurt Burton's career, as he would soon be elevated to the president's office.

Burton was fond of saying that the government's "dissolution" of Standard ushered in a new generation of younger thinkers and executives, and while he may have been one of these, the bottom line remained that the formerly related Standard's companies were still related, and observing an unofficial compact amongst themselves to restrict their sales to pre-1911 marketing territories. As one industry historian described it, "Oil continued to move from well to market through exactly the same channels as before, simply because there were no other channels. The solemn words of the United States Supreme Court Chief Justice had not changed the location of a single refinery or pipeline or marketing station."

No sooner had Standard been "dissolved," no sooner had the government passed the Clayton Antitrust Act in 1914, and then, in 1915, created the Federal Trade Commission to further thwart anticompetitive practices and elevate competition to the system's highest value, then Standard's luck came around again, with the outbreak of World War I.

When the War broke out, the government was "encouraged" to take a second look at its view of the value of cooperation with and within the oil industry. To fulfill demand that promised to exceed by stunning multiples any war that had ever been fought before, Standard and the other oil companies drew themselves even closer to the halls of government and persuaded them that they had to back off on the anti-trust stuff. Standard locked arms with its mortal rival Royal Dutch/Shell while its bonds with the military, which now ran its cars, trucks, planes and ships on oil, grew stronger by the day.

Oil was king, with countless new fields pumping, eighty percent of it came from America and the oil companies' primacy was officially cemented by their collaborations with the governments and militaries in WWI. When Lord Curzon, a member of Britain's War Cabinet and chairman of the Inter-Allied Petroleum Conference, said "The Allied cause had floated to victory upon a wave of oil," he spoke the truth. The Conservative politician's remark is still cited approvingly by the masters of petroleum, as the basis for the heroic tale they've liked to tell about their industry ever since WWI and, again, with even greater zeal, after WWII: that is, they supplied the oil that fueled the Allied victories. The good guys couldn't have won without them.

But Curzon's statement actually admits of a larger and more important truth — oil fueled both sides of World Wars I and II. Everybody was floating on a wave of oil, winners and losers alike, making his remark more meaningful in the nature of an observation about the time and the modern methods of warfare, rather than as a statement of a particular technical advantage adhering to the Allies, thanks to the oil companies' generosity or patriotism. Though they'd never tire of wrapping themselves in the American flag, Standard Oil Corporation and several other weighty American corporations were only too happy to help both sides in these conflicts, not just selling oil to the Allies' enemies but, as we shall see, also showering many a crucial additional kindness on them in wartime.

But, in spite of some wicked double-dealing, Standard's high-profile involvement in the American war effort and its newfound respect for public relations paid off handsomely. A corporate biographer identified the healing effect of the global conflict on the much-embattled company in the Nineteen Teens, when he observed, "the war had exerted a tonic effect upon morale. Jersey Standard's corporate inferiority complex [brought on by trust-busters and constant bad press] all but vanished. ... Washington seemed friendly and seemingly had come to appreciate the peculiar problems of the petroleum industry."

Old man Rockefeller had long contended that cooperation beat competition in business if the health of the enterprise and the good of the people were to be considered. Even the greatest defeat of Standard — busting the trust —ended up merely an extension of Rockefeller's philosophy. In his view, of course, what was good for Standard Oil was good for the people. And Standard had led a charmed life for so long. Yet, just when it seemed the good times would be drawing to a close, that change must come, it didn't.

Jamie Kitman is a NY-based lawyer, rock band manager, picture car wrangler, and automotive journalist. Winner of the National Magazine Award for commentary and the IRE Medal for investigative magazine journalism, he has a penchant for Lancias and old British cars, and is a World Car of the Year juror. Follow him on Twitter @jamiekitman and on Instagram @commodorehornblow.