When you think about the ideal small car, your mind might head to something like the Fiat 500, the Chevrolet Bolt or a neat little VW Golf. But these modern city cars look monstrous when compared to the world’s smallest car: The Peel P50.

Originally sold between 1962 and 1965, the Peel P50 is officially the smallest production car of all time. Measuring just 54 inches long, 41 inches wide and 47 inches tall, it has space for one human and not a lot else.

“I remember I saw a documentary, and it was narrated by John Peel and it starts with the original Peel cars,” says Jim Buggle, co-founder of British firm P50 Cars.

“Something about seeing the Peel P50 as a kid just took my interest. I remember going to school the next day and drawing one out and saying ‘I want to make these.’”

A few decades later and that’s just what Buggle is doing. Alongside business partner Craig Wilson, the pair set up the company P50 Cars to build brand-new, fastidiously accurate replicas of the world’s smallest car. From their workshop in southeast London, the duo assembles the standard P50 as well as an open-top Spyder variant.

Your brand-new Peel can be purchased as a kit to assemble at home, or as a fully-assembled car that you can drive right out of the company’s new factory.

P50 Cars recently moved into the new site, which has ample space for the company to ramp up production as orders flood in from around the world. When I visited the British shop this summer, cars were being assembled for delivery to India, Australia and Qatar. The microcar maker has shipped vehicles to every continent except South America and Antarctica.

“This is going to be the production line,” says Buggle as he gestures to one side of the industrial unit. “We’ve got this space for the shells in here, then next door is what we call the dirty side. That is where all the welding and the machining happens. We’ve also got a spray booth and the fiberglass and all that.”

Walking around the site, it feels like a fully-fledged car factory, but on a much smaller scale. Buggle and Wilson are still getting their bearing at the new site, but there’s an area filled with fiberglass P50 bodies, and shelves stacked with diminutive engines, tiny wheels and miniature brake assemblies.

In the neighboring unit, there are all the tools required to machine the components that go into each car.

“This is one of the brake hubs,” says Buggle as he gestures to a table of components required for each car. “It’s machined all next door and then we anodize it in-house. So we’ve managed to fit a disc assembly within the six-inch wheel.”

With the new factory up and running, Buggle and Wilson hope to build as many as 100 cars a year, a number that would tower over the output of the original company. Just 50 examples of the original Peel P50 were built over three years, with around 27 thought to be surviving today.

“There’s not loads,” says Buggle. “So we basically got as many photos as we could.... We managed to get a set of molds, which were basically shells that were copied off the originals. They weren’t perfect but we put a lot of work into perfecting them and tweaking a few things.”

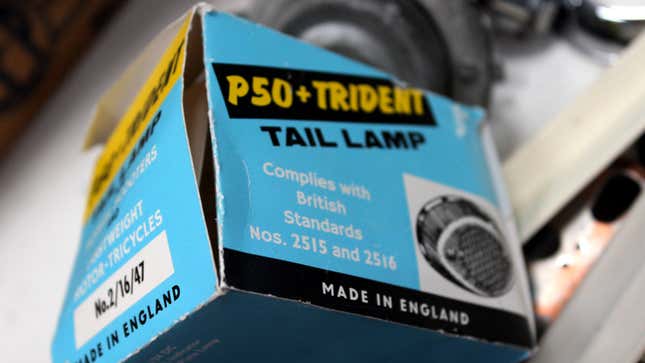

The molds are now used to craft new P50 bodies. Careful inspection of original hardware and a trove of photos of vintage P50s has helped the pair recreate every other component that goes into assembling the microcar. So many parts are custom fabricated in-house, from the bespoke taillights (modernized with LEDs) to a recreation of the horn on the car’s nose. It’s been a meticulous process for the pair.

“It’s to a point where, even now, when I see photos of our cars that I know are our cars, sitting next to an original, I have to take a few looks,” said Buggle.

Getting to this stage was no easy feat. Unsurprisingly, suppliers of parts for the world’s smallest car are few and far between. Often, when the pair think they’ve found a perfect component, it quickly goes out of production.

“One of our biggest problems over the years has been, when you finally sort a part that will be good, all of a sudden they don’t make them anymore,” says Wilson. “It’s happened so many times. We seem to have a knack for picking something we like and then they just don’t do it any more.”

This bad luck has come for the modern company’s supply of engines, lights, brakes and even wheels. It’s this inconsistency that inspired the duo to bring so much parts production in-house.

So How do You Make a P50?

“We start with making the suspension arms and things like that,” explains Buggle. “We’ll do things in batches, so once we’ve got a full set of parts, then we can start assembling them.”

Over the years, the pair has gotten the assembly of each car down to a carefully choreographed ballet.

“We worked out that the best way to do it is to put [the car] on its back — that gives you full access to the whole bottom of the car,” says Buggle. “You just have about enough reach to bolt everything to it without needing two people.

“Then, once the wheels are on and the engine is in, we put it on its wheels and work on the interior.”

On top of all this, there are the alterations, customizations and options. Customers can choose to buy a fully-assembled P50 or a kit, and the company offers electric or gasoline-powered drivetrains. From there, you select your paint color, interior upholstery, and a raft of other options.

“There are a lot of people who just turn up and think they can pick one up off the shelf and that’s it,” says Wilson. “But they’re pretty much bespoke, all of them.”

Who on Earth Is Buying New Peel P50s?

The simple answer is, loads of people. The P50's resurgence began when Jeremy Clarkson tried to spend a day driving one on an old episode of BBC’s Top Gear. With so few originals around, the best option for most people is a replica.

“If I had a pound for every time someone’s said, ‘I bet I can’t get in that,’ I’d make a fortune,” says P50 replica owner and all around microcar fanatic, Ian Leonard.

So far, Leonard has owned two of Buggle and Wilson’s P50 replicas, as well as an original from the 1960s.

Leonard’s obsession with microcars began when he was growing up. A neighbor introduced him to the Messerschmitt, a German three-wheeled microcar built between 1955 and 1964.

“When I got to a certain age, I thought to myself, right: I’ll set a goal and I either want a Porsche 911 or a Messerschmitt. And I bought myself a Messerschmitt and that was it, really,” Leonard told me. “I’ve never looked back and the obsession has grown from there.”

Now, Leonard is in the process of building what he calls the “mega garage” to house his collection of microcars, which currently includes a Peel P50 replica, a Peel Trident (the bubble-top, Jetsons-esque sporty variant of the P50), Messerschmitt, Messerschmitt Cabriolet and a Brütsch Mopetta. And having driven and owned both original and replica Peels, Leonard has spotted a few differences between the two.

“I mean, at the end of the day, the difference is the build quality, really,” says Leonard. “The original ones were sort of flimsy. They were very, very crude. They’re not very nice to drive and they vibrate. I mean, they all vibrate, but Jim and Craig have put a lot of thought into making the driving experience a bit better.”

Because of that, Leonard says he is happy to take his P50 out and about in Lancashire, in the north of England, where he lives.

“I drive it all the time,” he says. “I go up over Rivington in it, which is 1,300 feet above sea level. It really does struggle with the hills, but because it has a modern four-stroke engine you can really rev it and not be worried. Because it is so modern and mechanical and everything is so well built, I know that it’ll go up all these hills. It’ll go up them at like 20 mph and people might struggle to get past you, but it does the job.”

So, does this mean that the new replica Peels being built by Buggle and Wilson are an ideal daily runaround for the modern motorist?

“You sort of get used to it,” says Leonard. “You get in it and it’s a bit quirky, people are constantly looking at you, but it is very, very drivable.”

For around $16,000, could you see yourself switching to the microcar way of life? For one, you’d be getting your hands on a bespoke, hand-built recreation of a (tiny) piece of 1960s motoring history. When other companies revive something historic from the 1960s, they typically charge a few hundred thousand for their effort.