There’s rust in my hair and ears. Every muscle in my body aches. My house smells like mouse urine. The city of Troy is about to shit a brick when it sees what’s in my driveway. And yet I’m not even close to done with what I now realize is the totally foolish endeavor of turning two junkyard-bound parts Jeeps into a single functional machine.

At some point in the next couple of years, I will be driving a 1994 Jeep Grand Cherokee thousands of miles around the world in an effort to discover global car culture in a way that few have before. (If you happen to live anywhere outside of the U.S. and want to show me the car culture in your neighborhood, DM me on Instagram).

Since I’m a cheap bastard, I’ve decided to build my vehicle out of two $350 parts Jeeps that were each only days away from heading to junkyards. Unfortunately, it turns out, building what is going to have to be an incredibly reliable machine out of two vehicles on death’s door is much harder than I anticipated.

The Rare Manual ZJ Is The Best Budget Overlanding Jeep

Before I get into that, a bit more about my chariot of choice. I’ve always felt it’s a shame that the five-speed ZJ Grand Cherokee is as rare as it is (some say Chrysler built fewer than 1,400), because I consider it to be the greatest budget overlanding Jeep in the world. The ZJ offers a more reliable cooling system and more space and comfort than an XJ Cherokee while weighing only 400 pounds more; it’s significantly cheaper, simpler, and lighter than a JK/JL Wrangler; it’s more robust than a KJ Liberty; and its interior has more room than the coveted “LJ” Wrangler (and it can be had for a lot less money).

Sadly, ninety-nine percent of ZJ Grand Cherokees ever sold were equipped with fragile automatics, significantly tarnishing the vehicle’s reputation and viability as a trustworthy overlander. But, if you can somehow find a 1993 or 1994 stick shift model (or a rare early ’93 equipped with the XJ’s solid AW4 automatic) — especially one of the uber-rare base models with crank windows and manual locks (allowing you to forego the ZJ’s oft-maligned electrical gremlins) — then you’ve got a comfortable, spacious, reliable, easy-to-fix, off-road capable beast ready for overlanding duty.

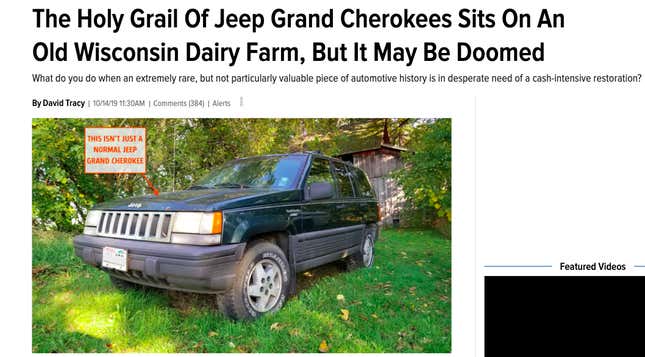

There’s a reason why I call the manual Jeep Grand Cherokee the “Holy Grail.” It truly is a hidden gem that doesn’t get the credit it deserves, even from the Jeep community.

Can Two Pieces Of Junk Make A Reliable Overlander?

Unfortunately, I will not be taking the rust-free black $700 “Holy Grail” that my friend Brandon and I fixed and drove back to Michigan from Colorado in 2019, as I recently sold that vehicle as part of my fleet-downsizing efforts. Nor will I take my beautiful red low-mileage Grail that I bought from Reno last year, as that’s just too nice to destroy in the mud pits of Brazil. No, instead I’ve fallen into my old ways and decided to take in a rescue. Actually, two.

The first machine in question is famous. I wrote about it back in 2019 (see image before the one above) — a rare manual Jeep Grand Cherokee about to bite the dust after a few too many salty winters in Wisconsin. “What should the owner do?” I asked readers before stating that the piece of American automotive history deserved better than to be crushed. Even though nobody besides me seems to give a damn about manual Jeep Grand Cherokees (“Rare does not mean desirable,” many commenters wrote), I still somehow convinced a quarter million people to read the article about the hard-to-find Jeep on death row on an old Wisconsin dairy farm.

Two years passed before Dustin, the Jeep’s owner, called to tell me the manual Jeep was headed to the shredder. That exact same week, a man from Virginia commented on one of my articles, saying his friend had a manual Jeep Grand Cherokee that he was selling as a parts car. For $350! The body looked good.

That parts car was this red beauty you see here. The previous owner, an awesome dude named Seth, had yanked the transmission and put it in his nice 1996 ZJ (which he’s selling, by the way). He was offering the red Jeep — which was not only a stick but also a base model with crank windows and manual locks — for parts and was planning to take it to a junkyard.

Both Dustin and Seth contacting me the exact same week about their soon-to-be-crushed Holy Grails was clearly a sign from the Jeep gods: I had to buy both machines and merge them.

Dustin’s parents dumped his green rustbucket off at my place for $350 total, and I drove to a lumber yard in Virginia and hauled the $250 (plus $100 for the transfer case) red carcass back to Michigan on a U-Haul.

The rest of this, you’d think, would be fairly straightforward. There’s a green Jeep that’s intact but made out of the same stuff as a Pittsburgh bridge, and there’s a rock-solid red Jeep that needs a transmission and a bunch of other parts that folks have picked off. Just crack some beers, swap parts, and have a good weekend, right? Wrong.

As this “Operation ‘Holy Grail Triage’” (as I’ve come to call it) has taught me, buying a rusty parts car with hopes to just swap its guts into another machine (especially if that’s also a parts car) is a horrible idea.

Parts Cars Take Up Space And Are Hard To Move

To get my Jeeps into my garage was a massive chore. Neither vehicle could drive under its own power, and neither vehicle has brakes. This presented a problem when buying the vehicles (Seth basically rammed my red Jeep up my U-Haul trailer ramps using his ZJ and a tire), and it presented a real annoyance earlier this week.

The red Jeep was literally frozen to the ground. Dustin had to yank the thing with his JL Wrangler to get it unstuck. We had to carefully tow both machines around my house, with me turning their steering wheels and having a wood block at hand, ready to throw it under a tire in case either ZJ wanted to roll into Dustin’s Wrangler.

As we didn’t want to pull a Seth and ram the Jeeps from behind to get them into my garage, Dustin drove his Wrangler into my backyard and pulled the two rare ZJs through a door at the front of my garage using a ridiculously long tow strap (see above). The whole thing was absurd.

Parts Cars Are, By Definition, Absolute Trash. So Expect To Deal With Bullshit

You have to realize that, as a general rule, a “parts car” is a “parts car” for one reason and one reason only: It is a steaming pile of shit. That’s literally the requirement for the job.

“Ah, I see you have 90 PSI in cylinder six; get the hell out of my office, and don’t come back until they’re all under 60!” is how I imagine the parts car interview process goes. “Did you really apply for this gig with five fully functional synchronizers? You disgust me,” the interviewer might tell a manual 2007 Dodge Caliber. “Please. I couldn’t hear even a tiny bit of howling from that ‘8.8' differential as you drove in. Apply again later,” the boss would tell an old Ford Explorer.

You get the idea. Choosing to build what is going to have to be an unkillable overlander out of not one but two parts cars — two vehicles so bad that their owners completely gave up on them and actually renounced their car-hood, their very automotive souls, and have now simply classified them as cobbled together automotive components — is a horrible idea, as I’ve been finding out while lying on my back these past few days.

Dustin’s green 1994 Jeep Grand Cherokee is the rustiest, most structurally compromised machine I’ve seen in years. Huge sections of its body appear to be made of brown rubber that just flops around when touched. When I bang on the SUV with my shoe or with a screwdriver, that rubber turns to sand that seems to want to rain down directly into my eye socket; when that’s full, the remaining flakes become a huge pile on the garage floor.

Dustin’s former Jeep has the structural rigidity of a soap bubble, and yanking parts from it has been rough. The saint-like former owner kindly drove from Wisconsin to help me in this endeavor; he and I have broken about 6.02*10^23 fasteners, ingested more Fe2O3, and wrestled with mouse urine-coated interior bits (those interior bits, now in my living room shown below, are making my entire house smell terribly; it’s not optimal) than any person should. This 210,000 mile vehicle that he’d daily-driven for the better part of a decade has very clearly had every bit of functionality squeezed out of it.

To get the headliner out, we had to remove a bunch of interior trim and open up the rear hatch. Removing the trim was okay, even though we broke a bunch of clips and had to drill out some rusty screws. Somehow, though, lifting the rear hatch was the tougher job. Jeep Grand Cherokees frequently have rear door latch troubles, but Dustin’s green Jeep was possessed by demons. The entire latch had been the lucky recipient of so much mouse fecal matter, salt, and moisture that what once might have been sliding metal latch components had turned into a singular hulk of brown rock.

We pulled off the rear trim piece that the license plate mounts to and found that we had decent access to the latch, but no amount of PB Blaster and prying could get the thing open. We had to cut open the rear hatch and destroy the latch with hammers, pry bars, and cutting tools.

Sliding under the Jeep to remove the transmission wasn’t great either. Of course, one of the weld nuts that receives a bolt to hold the transmission crossmember broke into the unibody rail, so Dustin had to cut that:

But worse than that was just toiling on the damp, cold cardboard we’d placed on the ground, leaning up to undo the bolts holding the transmission to the engine, and feeling every muscle in our necks and backs complain, painfully. At one point, it appeared as if Dustin were overheating:

All the while, it rained rust just about as violently as I’d ever seen from any of my previous corrosion-infected machines.

Cars Were Meant To Be Assembled/Disassembled In A Very Specific Order

My struggles with Operation Holy Grail Triage don’t have to do solely with the rusty state of Dustin’s parts Jeep, they also have to do with the sheer strenuousness of disassembling and assembling vehicles.

Cars are meant to be put together in a very specific manner. During the automotive development process, any time an engineer (ex: a systems integration engineer or a design and release engineer) adds or modifies a component in a vehicle, manufacturing engineers have to consider how those changes fit into an assembly process. Certain parts have to go first, because they literally won’t fit once certain other parts are in place. It’s all a very precise art.

This means that getting certain parts out of a vehicle requires disassembling lots of other components/systems. For whoever yanked the pedals/transmission/interior out of the red Jeep, that meant just hacking through those parts, leaving me with a broken mess to deal with. The most annoying example is the carpet, which Seth (bless his heart) tore out to remove the center console:

In the case of the green parts Jeep, this means I have to meticulously disassemble or break a bunch of parts I don’t need in order to get to other parts that I do need. It’s grueling.

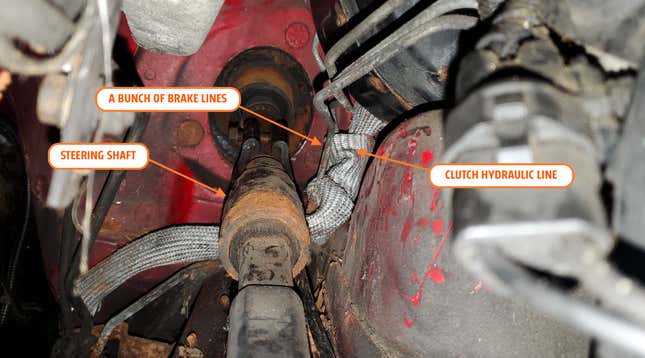

Dustin and I really struggled with the clutch master cylinder/slave cylinder (see clip above that shows the red Jeep). First, it’s a fragile part; a tiny pinhole leak in the cylinders/reservoir/line would render the whole thing useless. And unfortunately, the thing is routed underneath the brake booster, a bunch of brake lines, and the steering shaft! We managed to get the clutch hydraulics out of the green Jeep by breaking a bunch of the already-rusty brake lines, but we knew this wouldn’t be an option when trying to get the thing back into the red Jeep.

Luckily, Seth had removed the clutch hydraulics from the red Jeep by disconnecting the master and slave cylinders and not by breaking the brake lines. The poor bastard had to bleed his clutch hydraulics, but at least I don’t have to replace hard-lines; awful kind of him.

Still, getting the clutch hydraulics in wasn’t easy. We had to unbolt the steering column from the firewall, and we had to undo the steering intermediate shat at the steering box to allow us to snake the hydraulic line under. It’s not a great design by Jeep.

The Transmission Is In!

It took us three days of towing cars, breaking bolts, snaking parts out of tight spots, and struggling to remove upper bell housing E-TORX fasteners, but Dustin and I finally managed to install the green rustbucket’s transmission into the red Jeep. We’ve got a new transmission mount, a new clutch kit/flywheel, and a new clutch master/slave cylinder. The clutch seems to work wonderfully.

These parts weren’t cheap. The clutch kit was $125 and the new flywheel was about $90. Throw the transmission mount in there and the new clutch hydraulic assembly (which I bought from a reader for $50 IIRC), and I’m in roughly $250 already.

But these are parts I can’t really cheap out on, as they’re just too important. Losing a clutch in the middle of the Amazon rainforest would be awful, so I’m going to have to find ways to save money elsewhere. Hopefully I can recoup some cost by selling the engine out of the green Jeep (as soon as I know that the red Jeep’s engine runs, as it’s currently a total mystery) and by scrapping the body.

This Overlanding Build Will Be Epic

The rest of this build will involve installing a cheap lift kit, throwing on some used (but new-ish and nice) 31-inch tires, swapping in an axle from a Grand Cherokee 5.9-liter (this axle has a limited slip differential and shorter 3.73 gears) along with a front axle with the same gearing, bolting up some underbody protection, installing a winch, fabbing up a rear tire carrier, figuring out how to make the interior livable — there’s a ton of work to do, and it’s all got to be done for as little money as possible.

My goal is to build a reliable, off-road capable, livable, badass manual Jeep Grand Cherokee ZJ overlanding build for under $3,000. I don’t know if it’s possible, but then again, this whole ’round the world trip in a 30 year-old Jeep barely sounds possible.

That’s the beauty of it.

P.S.: In my first paragraph I wrote “The city of Troy is about to shit a brick when it sees what’s in my driveway.” I was referring to this Jeep carcass:

It’s not clear if that brick on the bottom right came from the city’s bowels.