There are some repair jobs so soul-suckingly awful that I can’t help but procrastinate on them. In my garage is a 1991 Jeep Cherokee that I sold to someone under the condition that I swap the rear leaf springs. Why did I agree to this? Because I am a fool, that’s why.

A few years ago, I bought a beautiful 1991 Jeep Cherokee that had been involved in a minor fender bender. A Chicagoan named Tracy had tipped me off, saying the vehicle, which her son had been piloting at the time of the crash, had been dragged off by her insurance company. If I wanted a nice stick-shift XJ, this was my chance to snag one for cheap.

After hellacious attempts to get my grubby hands on the perfect (but dented) Jeep XJ, I bought the thing for $2,000 from a used car dealer near Indianapolis. Then the Jeep just sat at my house, as I became too distracted by other projects. After spending years slowly repairing the machine, I got it looking great. Then I put it up for sale, because I needed to thin my herd.

Recently, someone asked me if they could buy the Jeep for my $7,000 asking price; for some reason, I decided to call Tracy up and see if she wanted her family’s Jeep back. Her dad, a former Warn Winch Company employee, had purchased the Jeep new as part of his company’s deal with Jeep. He might be keen to get the vehicle back now that I’d gotten it all fixed up.

Tracy’s dad agreed to buy the Jeep, especially after I offered him a discount — $6,500 — figuring he’d ordered the vehicle from the factory, so I’d love to sell it back to him; he’d appreciate it more than anyone. I mentioned that the rear leaf springs were flat, and offered to fix them; I don’t know why I did this. But the buyer said sure; he’d pay me $7,000 total if I swapped the rear leaf springs.

I snagged some new springs for $140, a set of lightly-used shocks for $30 (since I was hearing a clunk from the rear), and new fasteners for $75. So basically, I had agreed to swap the rear springs for $250 in labor.

I don’t regret this decision, since I want Tracy and her family to have a nice Jeep, and I’d feel bad if they had to pay a shop $1,500 (or whatever) to do the job. But trust me when I say: I would never do this job for $250 under any other circumstances. It is hell.

In my defense, this Jeep is rust-free and from Oregon. I figured it would be immune to the corrosion-causing ailments I’m used to dealing with on rust-belt machines. But the reality is that it doesn’t matter where a Jeep Cherokee XJ is from — replacing its rear springs is always going to be a soul-crushing job.

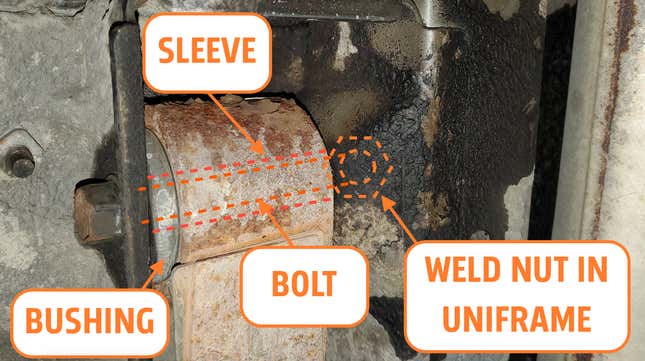

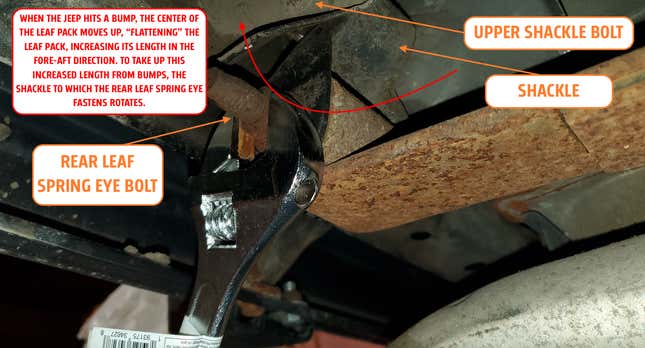

Before I go any further, allow me to quickly discuss the anatomy of a leaf spring. A leaf spring pack consists of a bunch of leaves all bolted together via a centering pin, which slots into a hole in the axle. The centering pin is important because it not only squishes the leaves together to create a single pack, but it also takes up the shear loads from the axle. Leaf springs are tasked not just with taking up vertical loads from road bumps, but also lateral loads (coil springs, by contrast, don’t take lateral loads, as they would just bend; coil sprung solid axle suspensions use track bars to handle lateral loads). At each end of a spring pack is a spring eye, which is part of the main leaf at the top of the pack. In each eye is a bushing with a steel sleeve at its center.

The problem with my XJ is that the bolts going through the front leaf spring eye bushings’ sleeves (see below) are either seized to the weld nut in the unibody, or seized to the metal sleeve. Either way, spinning the bolts out is borderline impossible.

If the fastener is seized into the weld nut in the unibody, and I crank on the bolt head with all my might, I risk breaking the nut off the unibody. Then I’d have to cut a hole in the frame or floorboard to get a traditional nut on the backside of the leaf spring hole in the main rail. God I don’t want to cut a hole in this Jeep.

If the bolt is only seized to the metal sleeve at the center of the rubber bushing, then as the bolt unthreads from the nut in the unibody (spinning the sleeve in the bushing), the bolt will be unable to slide out of its hole. As I tried to unthread the bolt, the sleeve would attempt to push the spring mount, which is part of the unibody. Since that won’t budge, the threads in the weld nut would likely be ruined, and I’d be back to cutting a hole into the Jeep to place a nut.

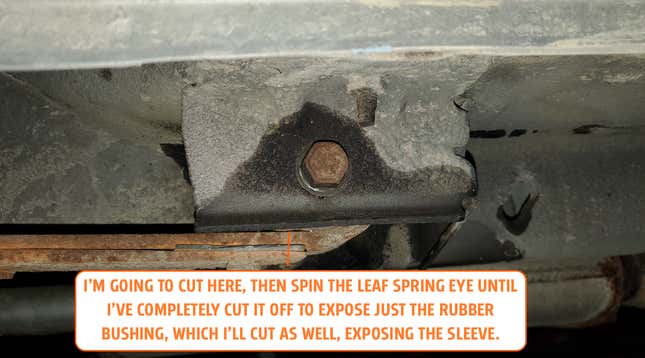

The solution, then, is simple, but awful. I’m going to have to cut my front leaf spring eye with an angle grinder, cut the rubber bushing out with a saw, and then heat up where the bolt goes into the unibody weld nut. Then I’m going to have to grab the metal sleeve with vice grips and rotate it until it’s unseized from the bolt, allowing the fastener to move axially without ruining the weld nut threads.

This is going to take forever. Cutting the leaf springs is going to be loud, slicing out the rubber bushings is going to be painstaking, and heating everything up and putting my back into undoing that bolt will ruin my spirits, there’s no question about it.

Then there are the rear leaf spring eye bolts (there’s one shown above). Luckily there’s just a regular, exposed nut and not a hidden weld nut. Still, the rear bolts have the same problem as the fronts — the nut and the sleeve are both seized to the fastener. I may just cut the two ends of each bolt off. I don’t have time to fuss with this nonsense.

Even though it wasn’t part of the deal, new(er) shocks were only $30, and this Jeep does need new dampers. So I’ll swap these out. The upper shock bolts, shown above, almost always break upon extraction. I’m hoping that this Jeep’s won’t break, given that they’re covered in differential oil leaking from a bad rear pinion seal. But we’ll see.

In any case, I have hours of work ahead, and it’s the type of work that’s just straight-up painful. These fasteners will fight me for every millimeter. In the end, though, I’ll be rid of a vehicle, and that — at least at this point in my life — will make it all worth it.