“Dude, you may want to go to a clinic,” my friend told me after I asked for advice on my feet, which hurt so badly I was having trouble walking. I had spent two straight weeks obsessively fixing a rotted-out 1958 Jeep FC-170 while living in a Toyota Land Cruiser, and in all the excitement, I had forgotten to take care of my body. This was a mistake — one that nearly forced me to give up on a vehicle that hadn’t run in many years and that was plagued by major engine problems. But I didn’t give up. I pushed harder.

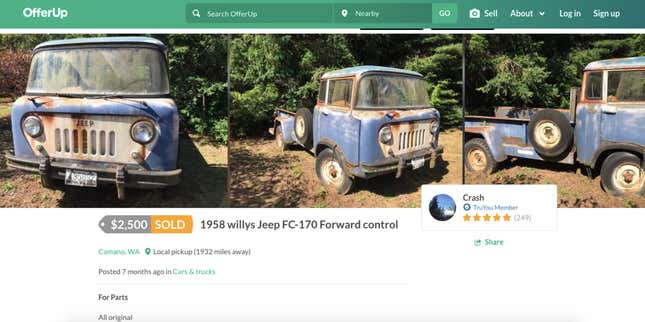

Back in the summer of 2020, Tom, a reader in Stanwood, Washington, emailed me a listing for a 1958 Jeep FC-170. Its relatively modest $1,500 asking price, the fact that it was on the west coast and therefore couldn’t possibly be as rusty as a Michigan Jeep, and its irresistibly cute styling led me to purchase it sight-unseen. I hoped to use the pickup as the basis for an electric vehicle conversion that I planned to complete with the help of automotive engineers as a way to learn more about EVs. But first I had to get the long-neglected Jeep 2,500 miles back to Michigan.

A smart man would have paid a transport company to truck the Jeep to Michigan. A man of average-intelligence would have simply picked up the Jeep and towed it back. Only a fool would have bothered trying to fix the Jeep, whose engine would be stripped out anyway during the EV conversion. Hello dear reader, nice to meet you. My name is David Tracy.

The idea of reviving a long-abandoned Jeep was too enticing, so in the spring of 2021, I bought a 2002 Lexus LX 470 (basically a Toyota Land Cruiser) tow vehicle that a Chicago reader had offered me. I carried my heavy tools onto a train from Detroit to Chicago, then through the busy streets of the Windy City, and then onto two other trains that took me to the suburbs.

Once in suburban Chicago, I loaded into the Lexus and — after a bit of a fiasco at a used tire shop — headed toward Seattle to finally see the Jeep. My goal was to fix the farm vehicle and hit some awesome trails out west; if I could drive the Jeep all the way back to Michigan (and ditch the Lexus), maybe I’d do that. But the priority was off-roading a legendary Forward Control.

Upon arrival in Washington (the Lexus had handled the 2,000 mile trek flawlessly — you can read about it here), I realized that the Jeep was in far worse condition than I could possibly have imagined. Attempting to fix the machine would take every ounce of my wrenching skill, and lead me to the very brink.

I met that brink ten days into the Stanwood, Washington wrenchfest as I prepared for another night of sleep in my Land Cruiser in a dirt lot by a river in Mt. Vernon. Panic struck me when I realized I had seen very little of The Evergreen State.

I’d spent every waking moment of the ten days in a garage hoping to get the Jeep running so I could explore the west in an epic Forward Control. But the Jeep kept taking up more and more time, and with significant engine problems, things began to seem hopeless. With money running out and my boss wondering what the hell I was doing, I was staring down the barrel of the biggest waste of time and money in my life. I’d have to tow the Jeep 2,500 miles back to Michigan; I would have no story worth writing about; I would have seen none of Washington.

In this panic, I knew I had a choice to make: Throw in the towel and spend a couple of days exploring Washington in the Land Cruiser before towing the FC back (at least this way the long trip wouldn’t be a total waste); or keep wrenching on a vehicle that almost certainly would not run, and risk wasting thousands of dollars and three weeks just to wrench in a garage that may as well have been my own in Michigan.

I chose the Hail Mary.

I Was A Fool To Think I Could Fix This

Let’s back up a bit to the very moment I arrived at Tom’s place in Stanwood. I had foolishly believed that any car that has spent most of its life out west couldn’t possibly be that bad. There’s no rust out west, after all. But it was that bad. Actually, it was worse.

The interior was infested with mice and their putrid droppings:

Rust abounded on the Jeep that had spent much of its life near Camano Island surrounded by saltwater, with holes in the truck’s cab corners, floors, bed, bedside, doors, and even just under its front grille:

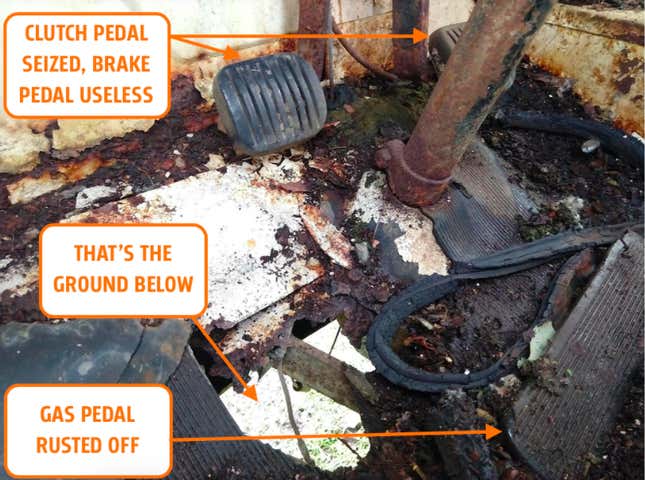

The clutch pedal was doing absolutely nothing, the brake pedal followed the clutch pedal’s example, and the gas pedal one-upped both of its neighbors by going AWOL. It had literally rusted off:

Not much more transparent than the decaying floorboards were the windows, whose cracks significantly compromised outward visibility.

The passenger-side door’s upper hinge was broken:

The carburetor was filled with mouse droppings, and based on what I could see, it sat upon an engine that likely hadn’t run in decades. It was completely covered in ordure and spider webs.

So that was my starting point. A rotted-out Jeep filled with mice, with a non-functioning clutch pedal, no brakes, no accelerator pedal, and a disgusting carburetor atop an engine that hadn’t run in forever. I knew as soon as I’d assessed the Jeep that this was likely going to be the battle that broke me.

I suited up and began cleaning. You can read how that went in my article “I Bought The Crappiest Jeep On Earth. Cleaning Its Interior Was Horrifying.” Or, if you need a motion picture to satisfy your content needs, you can check out the video at the top of this section and watch as I scream in surprise when a mouse jumps out of the piece of trash I’m holding. The clip shows me literally creating holes in my floors with a stick and a power washer, which I’m using to clean the interior that I’d covered in Bleach, Pine-Sol, and degreaser.

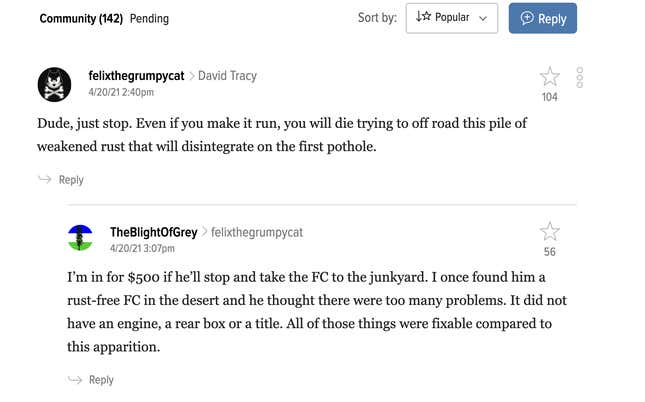

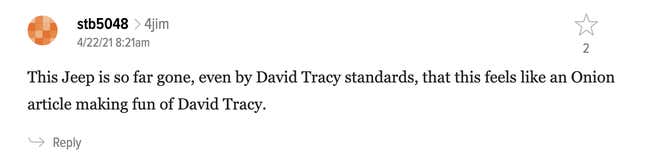

If you watched the video of me cleaning, or if you just looked at the other photos, and your first thought was “There’s no way,” you’re not alone. The comments on the aforementioned article communicated similar doubt:

“You will die trying to off road this pile of weakened rust that will disintegrate on the first pothole,” user felixthegrumpycat wrote; 104 people starred that comment. “I’m not at all convinced trying to drive this thing off-road in its current state won’t kill you” opined autojim; the words received 23 co-signatures.

These doubts fueled me.

The Wrenching Begins

The first thing I did after cleaning was remove the carburetor. Since this was a special dual-bowl carb that had been adapted to fit the FC, it wasn’t easy to get off. Tom had to custom-make me a wrench (he cut it in half).

Once the fuel/air mixer was off, I disassembled it with a flathead screwdriver, and dipped the rat poop-infested components (which all had a light dusting of orange rust on them) into a solvent overnight.

Rebuilding a carburetor as simple as the Carter WCD shouldn’t have been difficult, but that’s not how things work with farm vehicles that have seen hard lives. Upon cracking the carb open, I had discovered a broken throttle plate bolt, which I fixed by drilling a hole into the shaft, and slapping in a bolt and nut. It was far from an elegant repair job.

The carb also had a stuck jet. This is the little brass “nozzle” that shoots fuel into the engine, and it’s something that should be removed and cleaned thoroughly. Since mine was stuck, I grabbed a torch to heat the thing up, hoping thermal expansion would get the threaded little brass piece out.

This, as I wrote in my article “I Nearly Burned A Garage To The Ground Because Of A Foolish Wrenching Mistake” was idiotic. The carburetor and the table on which I was working were both covered in carb-cleaner, the most flammable substance in all of automotive repair. Read that article to learn about how I created a towering eight-foot flame that nearly burned Tom’s garage down.

Somehow, despite the immolation event, Tom allowed me to continue wrenching at his abode, and his wife Devon even continued serving me dinner on Tom’s Ford Fairmont in the garage (I wasn’t yet vaccinated, so we had to keep distance).

I cleaned up my charred carburetor, slapped it together using an incomplete and overpriced rebuild kit (I had to reuse the corroded mixture needles), and continued onward. This carb, I believed at the time, would likely never see use, anyway.

An Ominous Prognosis

I shouldn’t have been rebuilding that carburetor — or really, doing anything — before running tests on the engine. If the thing was truly hopeless, then a rebuilt carb would do me no good.

So, after Tom shoved the FC into the garage using his tractor, I drained the Jeep’s oil, and was pleased to see that it was free from obvious traces of water/coolant or any contaminants, and its flow rate aligned with what I’d expect from a 30-weight oil. This, along with the lack of visually obvious engine maladies (like a hole in the block), indicated to me that the Jeep had not been parked due to catastrophic motor damage. But to really tell if this Jeep had any chance of running, I had to conduct a compression test.

Compression — along with air, fuel, and spark (these three I could easily supply) — is the fourth ingredient that an engine needs to run, and it’s a function of the physical condition of the engine’s internals. This means the valves have to be able to seal against (in this case) the engine block (on a modern engine, the valves seal against the cylinder head), the piston rings have to seal against the cylinder bore, the gasket between the head and block has to seal, and there can be no cracks or holes in the piston, block, or head. If an engine makes compression, you can make it run. If you can’t get it to make compression, it’s over. It will never run.

To check compression, you plug a gauge into a spark plug hole and turn the engine over with the starter. The pistons move up, squeeze air, and the gauge reads if that air has been squeezed sufficiently to allow for combustion.

I had an issue getting the FC”s starter to work, so I removed it, accidentally dropped it three feet from a workbench onto a concrete floor, and noticed that the starter seemed to now function perfectly. I reinstalled it and conducted a compression test. The results were terrible:

A healthy engine’s compression numbers would have read between 125 psi and 140 psi. The numbers my engine made? Between zero and 30 psi.

“It’s over. This engine is toast,” I thought to myself, concerned that the cylinders had rusted out from sitting so long, or that the piston rings had broken or that the cylinder walls had large gouges in them.

Investigating The Demons Inside My Engine

The next step was to remove the top of the engine (the cylinder head), and peer into the depths of that Continental 226 flathead motor. It took forever, but I eventually undid all 30-ish bolts holding the head on, and the only casualty was the single thermostat housing bolt that I broke and that Tom generously extracted later using his welder.

With the head unfastened, Tom banged on it with a rubber mallet. Then, through the doghouse opening between where a driver and passenger’s seat would have been had mine not been completely chewed up by mice, he grabbed the cylinder head and yanked it up and towards the front of the Jeep before setting it on a workbench. This revealed the demons in my motor:

Look at all of that nastiness surrounding those valves. The intake valve of cylinder three seemed to have some sort of disease:

Let’s have a closer look; what are these little bubbles? Are they demons?

All of the valves were covered in filth and appeared to have some rust below the gunk. As for the cylinder walls, which Tom had lubricated with automatic transmission fluid prior to turning the engine over, those looked fine. Cylinder five had a few streaks of orange where water had dribbled down the cylinder wall, but otherwise, the walls looked clean:

Tom and I ran our fingers down the walls to check for grooves or deep ridges that would indicate lots of wear, but things seemed smooth:

The cylinder head, too, appeared to be in great shape. There was plenty of carbon buildup on it (and on the tops of the pistons), but for the most part, everything pointed to the valves as being the most likely cause of the compression issue.

Having opened the engine and discovered horribly corroded valves, it was now time to figure out how to get those valves out; this would require a special tool, so I put a call out on Instagram for a valve spring compressor. Luckily, a man named Jonah who lived about an hour south, closer to central Seattle, reached out. I was scheduled to meet him the following day.

Tom had headed into his house to tuck his kids to bed; I followed his kids’ leads, and turned in for the night, shutting off the garage lights and locking the door behind me. “Turning in for the night” meant driving 20 minutes to my go-to spot along the Skagit River in Mt. Vernon:

Temperatures were usually in the 40s, and trains would ride over that bridge and wake me up, but for the most part, sleeping in that Lexus’ second row was peaceful. For the most part.

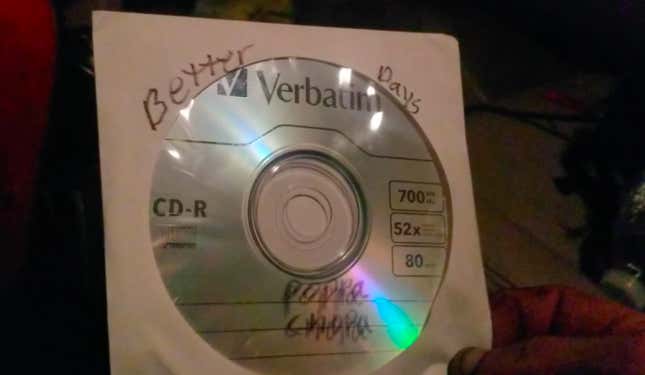

A few days prior, while I was at Walmart picking up some dirt-cheap gear oil for the FC’s axles, a man ran up to my car. Oddly, my first instinct wasn’t “I’m getting robbed,” but instead “Yo man there’s a pandemic. Give me some space.” A young man apologized and stepped back. “Hey, I just wanted to see if you wanted to buy a mixtape.” The guy seemed nice, and I was a bit flustered, so I just chucked him a $5 bill, and he handed me a CD.

The CD, which you can listen to on Poppa Chopa’s Soundcloud, is simply the most incredible example of musical genius I’ve ever experienced. You can see my review in the Instagram post above. Needless to say, it cheered me up just before I snoozed away in that dirt lot until the morning.

A Closer Look At Those Awful Valves

I spent much of the following day struggling to remove the bolts holding the intake and exhaust manifolds to the side of the engine. It’s not just that the bolts were rusty, it’s that their heads were so close to the manifolds that getting a wrench around them was borderline impossible. I had to use open-end wrenches and rotate the bolts 1/1000000th of a degree at a time. And what was worse was that, upon removing the manifolds, it was clear that they weren’t exactly flat due to pitting, so an intake and/or exhaust leak was pretty likely.

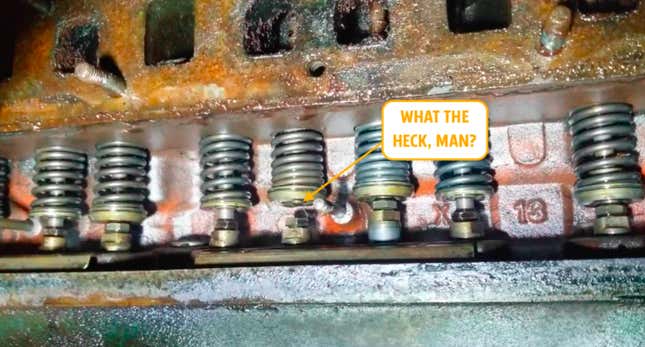

With the manifolds off, I could take the cover off the side of the motor and have a look at the valves. Here’s what I saw:

What the hell? Look at the valve I’m pointing out in the image above. It’s just stuck. The spring is pulling the bottom of the valve stem down with tremendous force, but the valve remains open!:

Obviously, a valve that won’t close won’t allow the moving piston to build compression. Clearly, there was some corrosion/gunk buildup causing the valve to stick; this, I guessed, was the primary cause of the bad compression across all cylinders.

After heading to Tom’s garage from my spot by the river, and after having spent a few hours gaining access to the valves, I headed towards Seattle to meet with Jonah, who handed me his valve spring compressor after showing me his own FC project and his beautiful Jeep Gladiator:

After two or three nights by the river in the Lexus, I slept in dirt-cheap ($65/night) motels so I wouldn’t have to be covered in oil for too many consecutive days. I enjoyed the reprieve of a motel, and then returned to Tom’s garage for the sixth day in a row.

I used the tool to compress the springs and remove the cone-shaped keepers connecting the springs to the valve stems. That allowed me to pull the valves out of the top of the engine, where I saw the real carnage:

The valve seats, against which the nice, smooth valves were meant to seal, looked like the surface of mars. Corrosion created deep pits into what should have been a glossy surface; these seats weren’t going to hold any fluid in, much less air.

I brushed the seats with a brass-bristle brush, and sprayed them down with brake cleaner. Things looked less disgusting, but craters remained:

As for the valves themselves? Well, they were pretty well ruined.

To get all the rust and grime off the valve shown above, I had to use a drill with a steel-bristle brush. After much toiling, the best I could do was a replica of the moon’s surface:

At this point, I was pretty well convinced that this engine was never going to run properly. Maybe it would pop off on a few cylinders, but given all the pitting in the engine, given the pitting on the manifolds, given my crappy carburetor rebuild kit, given that literally zero out of three pedals worked, given that I knew nothing about the state of the transmission or the rest of the driveline or electrical system for that matter, and given that I was almost 100 percent sure the fuel pump didn’t work (fuel pumps that sit always go bad), this all just seemed pointless.

But in the very back of my mind, there was a tiny flutter of hope. I knew based on my history that hope had a tendency to out-muscle any logic that might try to convince me that this was a bad idea. And believe me, logic put up a hell of a fight, sending me into a panic. Blood rushed through my circulatory system, and I began pacing back and forth in Tom’s garage at midnight. An internal slugfest was taking place as logic fired a devastating weapon directly at hope.

That weapon was the realization that I was 10 days into my trip, I’d spent over $1,000 on gas, food, tools, and motels, and all I had done the whole time was run around looking for tools and parts, and clean/fix a rusty Jeep in a garage. If the Jeep didn’t run — and there was a very high likelihood that this would be the case — I’d just be towing the thing back to Michigan, having wasted two weeks. “How was Washington?” People would ask. I would have no good answer. I wouldn’t even have an article. My boss would ask about that, and I’d say “It didn’t work out.” At the very least, if I quit now, I could travel around Washington, go hiking, and save myself from the almost certain embarrassment and waste.

Hope stumbled from this humongous blow, fell to the ground, and lay motionless. For minutes, it appeared dead. But then it staggered to its feet and, using a dream of this mighty FC off-roading somewhere in the mountains out west, slayed logic, just as it has in every one of my previous wrenching endeavors.

I got back to work.

I slapped duct tape onto the valve’s crater-filled combustion surface. This would allow me to hook a suction cup to it. That suction cup is part of a hand tool that one spins between one’s palms, back and forth; this rotates the valve, causing abrasion between the valve face and the engine’s valve seat. A special abrasive valve lapping compound, shown below, facilitates the creation of a nice, smooth new interface between the valve and seat.

As you can see above, I threw the hand tool away and broke out a drill. I needed to lap the shit out of those valve seats; to do that by hand would have taken millennia.

So I slapped a bolt into the drill’s chuck, slid the suction cup over the bolt head, popped the suction cup onto the duct tape I’d attached to each valve’s combustion face, squeezed lapping compound onto the valve face, and slid the valve stem into its guide until the face was touching the engine’s valve seat. Then I pressed that trigger, spun up the valve, and put my elbow into forcing that valve hard against that seat.

I kept applying downward pressure as the valve, spinning at hundreds of RPM, started cutting away at the valve seat. I could hear a low-pitched buzz and feel the vibrations through the drill as it did its thing.

One by one, I removed valves using the borrowed tool, scrubbed and washed them and their seats, then put duct tape and a suction cup on their combustion faces and spun them up against their valve seats, with lapping compound in between. Each valve took half an hour, and with breaks in between, we were looking at an eight hour job.

It was a slog that lasted late into the night, and at about 1 a.m., I began making stupid mistakes. While removing a valve, I dropped one of the valve keepers somewhere into the engine. I later used a borescope to look for it, to no avail:

In the end, I had to drain the clean oil I’d poured in, slide under the Jeep, undo the numerous bolts holding the oil pan in place, and recover the keeper:

Another major error I made late that night was placing the valves on a box, which I marked with a sharpie to indicate which valve seat it corresponded to (since the valve and the seat are ground together, they must be a matching set). I should have shoved the valve stems into the box instead of standing the valves on their combustion faces, because Tom walked by and accidentally bumped the box, mixing all the valves up.

I was three-quarters the way through the job, but now I had to do everything from the top. I gave up for the night, drove to my spot in Mt. Vernon, crawled over the center console, draped my crappy $9 Walmart sleeping bag over my body, and passed out.

When a train woke me up the following morning, something was wrong. My feet were killing me. I hadn’t taken my boots off in probably two days, because I’d been so focused on mending this Jeep that sleep and all other forms of bodily care had taken a back seat. I slept six or seven hours because I had to to prevent stupid errors, but when I was awake, 100 percent of my mental capacity went towards that Jeep. The result was that I could barely walk.

It felt like I was standing on silly putty. The bottoms of my feet were mushy, wrinkled, and cracking. The excruciating pain I felt when I stepped made me wonder if this was why Lieutenant Dan told Forrest Gump and Bubba to always wear dry socks. I had joked while wrenching on the broken FC that I was “In the trenches.” But somehow, it seemed, I had actually gotten trenchfoot.

I knew I had to lower the intensity of my wrenching focus. I snagged some hydrogen peroxide, booked a motel room, and soaked my feet. I washed them, used foot powder to keep them dry, and picked up a pair of flip-flops. Then I headed back to the garage and got back to the valve lapping.

One by one, I spun up those valves and ground them into their seats. I showed no finesse or mechanical mercy. If this Jeep was going to run, it needed tough love, so I leaned into it until I saw at least a continuous silver ring around all 12 of the valve seats. There was still plenty of pitting, but maybe, just maybe, those valves would seal against those silver rings. Maybe.

The Stanwood Miracle

With all 12 valves in place, I spent another few hours bolting the cylinder head, intake and exhaust manifold, and exhaust pipe back on. I put the head bolts in dry (this, I’d later learn, was a mistake), but lathered the intake and exhaust manifold with brown sealant to make up for the pitting that I worried would create a leak and prevent the machine from running properly.

But the manifolds were the least of my worries. I was concerned that, as much time as I’d spent lapping those valves, it hadn’t been enough. Or that the piston rings were indeed worn or broken. Or that there was a microcrack in the cylinder head.

To see if all my work had helped at all, I ran a compression test. This was it. The moment of truth. Whether the engine would ever run would be answered right here, right now. I threaded the tool into the first spark plug hole, and jumped the starter motor with some cables hooked to a 12-volt battery. The engine spun up quickly, the piston squished the air, the valves tried their hardest to hold air in the combustion chamber. But it wasn’t enough.

Forty to 50 PSI. My engine was supposed to make 125. A decent engine can run on 90 PSI. A worn-out engine can putt along on 60 PSI. But 40/50 PSI? That was trash. This engine would not run. It was time to put down the wrenches.

But I couldn’t.

Logic told me that, per the numbers, this engine could not run. And if it did, it would make no power. “That’s basic science, and David, you’re an engineer. You know it’s over.” But hope once again fought back as it always has. “Maybe those valve seats just need to wear in?” hope responded, “Maybe your starter wasn’t cranking hard enough due to a low battery?” Logic knew there was no use. He jumped down from my left shoulder, leaving hope as the still-undefeated victor.

So I installed the distributor, figured out how to wire up the ignition system with new points and a new condenser, bolted the carburetor in place, and then got ready to see if there would be even a hint of life from this motor.

Tom joined me for this part. He’d bought me this Jeep, stored it on his property for over six months, and pushed it into the garage. He’d been feeding me and lending me a wrenching hand when I needed one for nearly two weeks. He wasn’t going to miss a chance to see if this machine would at least fire on one or two cylinders.

After threading in spark plugs, hooking up the wires, and troubleshooting some ignition issues, Tom sprayed some starting fluid into the carburetor. I turned the key to crank the motor. The engine spun and spun and spun, but nothing happened. It seemed we had spark, fuel, and air. But apparently, we didn’t have compression.

How disappointing.

“Hmm, maybe the choke is blocking the airflow,” I said, still grasping onto a tiny strand of hope. I shoved a wrench down the carb to hold the choke plate open, and cranked the motor. “POP! POP!” I heard.

I turned to Tom, whose eyes met mine as we both cocked our heads with a look that said: “Maybe?”

Tom sprayed a bit more go-juice into the carb. I turned the key. “POP! POP! POP! POP!... POP! POP!” Holy crap, it ran a little. It was only a second or two, but it was more than nothing! Tom guessed it was about four of the six cylinders that had fired. Not bad.

We poured some gas down the carb to get it to pop off a bit longer, and we even got it to rev a bit, but again, just for a few seconds, and on who knows how few cylinders. Given what I knew about the inside of that engine, I kept my hopes low.

We needed to get the Continental flathead-six a steady supply of fuel, and since the old fuel pump was toast and far too expensive to replace, I decided to take advantage of gravity. Tom had a blue radiator overflow reservoir for a Ford Mustang sitting around. We filled that with a quart or so of gas, tied it to the Jeep’s rearview mirror (which amazingly didn’t fall off), and sent a hose from the dangling tank directly into the carburetor.

Fluid flowed from the tank and filled the carburetor’s bowl. “Ready?” I asked Tom. When he responded with a “yep,” I turned the key, but nothing happened. I pressed the carburetor’s throttle linkage by hand a few times and listened as the accelerator pump squirted gas into the engine. Then I turned the key again.

What happened next was a miracle — the single most satisfying moment in my decade+ of wrenching experience. That hopeless engine in that rusty Jeep that had probably been sitting for 30 years actually ran. And not only did it run, it idled. Beautifully:

Tom couldn’t believe it. My mind was blown. The crusty valves. The mystery that was the condition of the piston rings. The shitty carburetor kit. The pitted intake and exhaust manifolds. The compression readings. Somehow, against all of these odds, the motor sprung to life with vigor.

I Can’t Try To Drive It Until I Have Brakes

After running around the Seattle area searching for a tow hitch for the Lexus, I spent far too much time installing it via rusty threaded holes in the frame; then cleaned about three pounds of FC rust crumbs from Tom’s garage floor before preparing to head east.

First, Tom towed me through his yard using his tractor so I could test out the Jeep’s gears (they seemed to work?); he then pushed my rustbucket onto the trailer that U-Haul had lent me. The kind man who had bought a Jeep on my behalf, stored it for over half a year, fed me, and helped me resuscitate a long-dead Jeep said goodbye, and I drove off to search for brake parts.

I spent that night in the Lexus again, this time just feet away from a junkyard fence.

At the yard, I met Jonah, the man who had lent me his valve spring compressor tool. He helped me pick up a bunch of parts, including a clutch cable, since my Jeep’s was too stretched to actually disengage the clutch.

I never did use the junkyard cable, since Tom had rigged up an eye-bolt to pull the cable down to remove tension. It was a janky fix, but I knew better than to mess with a working system.

Following the amazing junkyard visit, I bounced around from AutoZone to Advance Auto to Napa to O’Reilly. All around the state of Washington I searched for rare FC brake parts. A reader sent me an O’Reilly Auto Parts link that showed the exact wheel cylinders I needed (they were hidden on the website); I ordered them from a man so excited to see my Jeep, he could barely contain himself:

The parts arrived, and my Lexus towed the Jeep east to the town of Ellensburg, where I met a reader named Jay, who had invited me over. A Volkswagen fan, Jay showed me his VR6-swapped VW Golf Cabrio. It was a tiny VW with a big motor that absolutely screamed through the rural roads outside Ellensburg, sound bouncing off the beautiful mountains nearby:

Jay volunteered to help me rebuild the Jeep’s entire brake system. That meant installing and bleeding a master cylinder and four new wheel cylinders, and — the hardest part — bending and flaring all new brake lines.

I’m pretty good at flaring brakes, but I was beat. I wasted hours screwing up the flares by using the wrong tool, but was lucky to learn that Jay was a master flare-er. Just look at this:

It took us three days total to go through the brakes. The college counselor introduced me to his beautiful family and showed me around town between wrenching sessions, during which I crawled under the rusty vehicle to take measurements and install brake lines.

I spent a few nights in a motel, and allowed my feet to make a full recovery. While looking into the motel mirror, I noticed just how much rust had fallen onto me while crawling under the Jeep. It was in my ears and eyes:

I had to run into town and borrow a drum brake removal tool from a vintage VW mechanic, but aside from that, the job went smoothly. In the end, our brake system looked superb.

We had all new brake lines, new hoses, a new master cylinder, and four brand new wheel cylinders — all fully bled. Jay at one point tried pumping the clutch pedal since there were only two pedals and he got confused, but I showed him that the right pedal is the brake pedal, and we eventually got the brake feeling nice and firm.

I greased all the Jeep’s joints and filled the differentials, transfer case, and gearbox — the latter two of which were filled with water (see above). Were my transmission and transfer case gears and bearings rusty? Probably. But hopefully they weren’t that rusty. I swapped one radiator hose, and filled the engine with coolant.

I was a bit concerned that all of that coolant would run out of the radiator, since it had suffered damage from an apparent impact, but whatever. I didn’t care at this point. I didn’t even know if the water pump would work or if the gearbox would work. The fact that the engine ran was a miracle unto itself; I wasn’t about to worry too much about a bad radiator. If it was toast, it was toast. All of this was in God’s hands at this point.

The FC Lives

We rolled the Jeep into Jay’s driveway, and I got ready for what could possibly be an inaugural drive if the Jeep Gods allowed. I had installed a hand throttle using a choke cable, since the gas pedal was gone. The “gas tank” dangled from my rearview mirror, and my electrical system was jankily wired-up directly from the six-volt battery to the coil. I used a 12-volt battery from the Lexus for the starter motor, since the six-volt didn’t have enough to turn the engine over quickly. The Jeep fired up!

Sitting on a towel, I pulled the throttle knob to give it a few revs, and quickly jumped out of the Jeep once the engine fan — sitting just a few inches to my right — shot something directly at my face. I reinstalled the engine cover, pressed the clutch pedal, put the transmission into first gear, and prayed as I slowly let off the clutch.

The Jeep moved. It moved!

I pressed the gas pedal and drove up the street in front of Jay’s house. A huge cloud of smoke shot from the Jeep’s exhaust pipe, creating a giant cloud above the neighborhood. Inside the Jeep, steam rose from the engine growling loudly just a few inches to my right, filling the cabin. I coughed as the hot vaporized coolant entered my lungs, but the joy of driving the machine that seemed completely hopeless just a few days prior dominated my mind. I pressed the clutch in, shifted up, right, and up into second gear.

The flathead six sang, and the Jeep cruised at 20 mph. The interior was deafening; gear noise, engine noise, 40 year-old-tire noise, boiling coolant noise, and occasionally fan-hitting-shroud noise made the interior inhospitable to anyone not as in love as I was at the time. I pulled the shifter down into third, and smiled to the Jeep gods who had somehow, some way, given this Jeep that had driven 0 mph for probably 30 years another chance at life. Unbelievable.

I returned to Jay’s house, poured myself out of the Jeep (which had died for some reason), and with a huge smile on my face, declared that it was time to go off-roading!

Top Of Idaho, Here We Come

I headed west towards the beautiful mountains of Idaho, where I planned to explore some off-road trails. The problem was, I knew that my quart of gasoline hanging from my rearview mirror wasn’t going to get me much farther than maybe a few miles, so I stopped by a Home Depot in Spokane and bought some wood.

Jay had given me a five-gallon jerry can, so I shoved a big wood post into my Jeep’s bedside, using a wooden wedge to keep it tight. Atop the post I screwed an eye bolt, to which I hung the jerry can with 550 cord. I ratcheted my new fuel tank to the pole to keep it from moving.

Right across the street from the Home Depot was a store called “House of Hose” (No, I’m not kidding). It sold hoses, fittings, valves, and other hose stuff. I bought some hose and a slick shutoff valve there, and plumbed in a fuel filter. One end of the hose went into the jerry can atop the post just behind the cabin, and the other end went through the passenger’s-side window, straight into the carburetor.

While in that parking lot, I painstakingly removed the 30-ish cylinder head bolts so that I could lather them with sealant and add washers to make sure they weren’t bottoming out. I should have done this in the first place, since the bolts go into the engine’s cooling jacket, causing all the steam to billow from the engine bay. But after a few hours, I was done. I slept in the Lexus in a Burger King parking lot.

The following morning, I drove to Coeur d’Alene, asked a gentleman at a gas station where I could off-road, and ended up at a parking lot at the base of a mountain. I lowered the trailer’s ramps, installed the jerry can pole into the bed of the Jeep, plugged the hose from the carb into the can, opened the valve, and fired up the machine.

Once off the trailer, I pointed the Jeep towards a dirt road heading uphill. At the time, I thought this was a mostly flat trail heading to other trails in the woods, but I quickly learned that this road was taking me up a tall mountain. My Jeep’s very first test would be a drive up a steep mountain; gulp.

Huge plumes of smoke filled my rearview mirror; I bet it looked like a forest fire from afar:

I just prayed. Was this engine about to croak? How long did I have left? It could be any moment now. But the Jeep continued to climb. We were half a mile in. One mile. One and a half miles.Then it happened; the Jeep cut off.

I ran to the front of the Jeep and looked under for oil pouring out of the crankcase. There was none. I opened the engine cover; everything still looked intact. “Did the engine seize?” I wondered. I put the Jeep in reverse, rolled back, and let off the clutch. The engine turned over fine. I looked around and saw the wire taped onto my battery post on one end and bolted to my coil at the other. It had come off the post; I had lost spark.

I jammed that wire into my battery cable, bump-started the Jeep in reverse, and it fired back up! I pulled the hand throttle and remained in awe of this 1958 Jeep continuing to ascend the mountain. It climbed and climbed and climbed. Smoke in my rearview mirror became thinner and thinner. The Jeep felt powerful, too; the torquey motor was dispatching this steep dirt road at low revs, not straining itself one bit. Ten minutes passed, and my heart pumped rapidly as the excitement of what was happening took hold. Ten more minutes passed. We were four miles in, and the Jeep just kept trucking.

After over an hour taking in the beautiful views of Idaho mountains, I reached what felt like the top of the state.

I couldn’t believe what I had just experienced. How was this working? The wooden-post-mounted jerry can was feeding gas into a hastily rebuilt (and charred) carburetor sitting on a pitted intake manifold bolted to a thoroughly-corroded engine that had never made more than 50 PSI of compression in my testing. The motor somehow turned that fuel into combustion, making power and sending it through a transmission and transfer case that had been filled with water. I was sitting on a towel, applying gas with my right hand, and pressing a clutch whose cable we stretched with an eye bolt.

In its very first off-road test, the Jeep had climbed a literal mountain, and now seemed to be running better than ever. No smoke shot out of its exhaust pipe. No steam billowed from the engine doghouse. The FC was thoroughly alive.

Glacier National Park, Another Man From A Walmart Parking Lot

The mighty Lexus tugged the FC on I-90 east until a sign for Glacier National Park lured me to take the exit for Kalispell, where I stopped by a Walmart to replenish the oil the FC had burned while climbing the mountain (quite a lot). In the parking lot, a man named Phil recognized me.

“Hey, is this the FC from Jalopnik? I’ve been following you!” he exclaimed. As someone who had had recent success meeting folks in Walmart parking lots (see: Poppa Chopa), I engaged and had a great conversation. “Hey man, if you need a place to wrench, let me know,” he offered.

I needed to move my precariously janky front tires to the rear and the less-awful tires to the front of the Jeep where all the weight was, so I actually took Phil up on his offer. “Okay, I’m at work for a bit, but I’ll take off and we’ll meet at my house in a few hours. I’ll text you the address,” he told me before suggesting a bomb burger joint.

A few hours later, I was in an incredible garage on a majestic piece of property in rural Montana. There were horses, mules, chickens, dogs, and children frolicking. It was beautiful.

Phil put my Jeep on his lift, and we swapped the tires around. I had a chance to look under the Jeep, and I must say: I was pleased. Things looked pretty decent down there!

Phil, an engineer-turned-pastor, offered me some helpful spiritual advice before telling me where to go in Glacier National park; then he said he’d hook me up with a member of his congregation who would off-road with me the following day. “Go to this bar parking lot at 8 A.M. tomorrow. My friend Zac will meet you.”

From Phil’s ranch, I drove to lake McDonald and shot the following video. After weeks of updating my Instagram, I had gone radio-silent for days. People wondered what had happened with the FC next. Now they would find out the glorious truth; it lived!:

I drove around that beautiful lake with the engine cover lid open and my right hand both shifting gears and applying throttle via a hammer I pressed against the carburetor linkage (the hand throttle had failed).

My left hand steered, my left foot clutched, and my right foot had only the job of braking. After two weeks of hellish wrenching and living in a Land Cruiser, this drive around one of the most beautiful places in the country was everything I needed to get my spirits back up. It was epic.

A Full Day Of Grueling Off-Roading: The Ultimate Test

I met up with Zac the following morning. A bearded, lanky outdoorsman with a quiet demeanor, Zac showed me around his 80 Series Land Cruiser before leading me to “Wild Bill” off-road course.

Once there, I dropped the trailer’s ramps and fired up the FC. This is a good time to mention how absurd the FC’s starting sequence is.

Starting The FC

To start the FC, step one is to pop the Lexus’s hood, remove its battery, and throw it into the FC’s bed.

Step two is to install the fuel can, which I kept tied to the pole in the bed of the FC (the rusted-off tailgate propped against a large spare tire kept things from falling out on the highway). That meant shoving it into the bedside stake pocket.

Then I had to jump into the bed and slip the hose whose other end was plumbed into the carburetor into the fuel tank. Then I opened the valve.

Next, I used a hand pump to siphon the gas from the jerry can down into the bottom of the hose, which I quickly shoved into the carburetor. This was a messy process involving gasoline getting all over my hands.

Then I hooked a coil wire from my six-volt battery (which just sat on what was left of the passenger’s floorboard) up to my ignition coil (pulling this wire was the engine shutoff).

Finally, I grabbed the jumper cables which I always had hooked directly to my starter motor, and touched them against the Land Cruiser battery in the FC’s bed. This jump-started the starter, cranked the engine, which now had fuel and spark. The motor fired right up.

The FC Conquers The Trail

I’d driven the FC up a mountain dirt road and around a beautiful lake, but I hadn’t really done any real off-roading. I had no clue how the Jeep would do when the going got really tough, but as soon as I hit the trail with Zac, we wasted little time easing into it.

I guided the Jeep’s nose into deep pits, over big rocks and stumps, through thick mud. In low-range and first gear, the Jeep just crawled. Those 32-inch tires, as old as they were, had grip for days. And that big inline-six made so much torque, I barely had to apply the hand throttle. Which is a good thing, because it kept sticking to the point where, when I did need to apply throttle, it’d let go and shoot the revs way, way up, jerking the Jeep forward.

Honestly, the Jeep’s cabin was terrifying off-road. With no front end, anytime the nose dipped into a pit, I felt like I was going to crash right into the earth. The rear end, with no weight to hold it down, regularly shot up violently, and scared the crap out of me. But nothing was more scary than the sound the Jeep made under load.

Gear noise, bearing noise, and engine noise — as loud as they all were — didn’t hold a candle to the horrific sound of what I could only assume was the engine fan rubbing against the shroud. It sounded like I’d imagine the Titanic sounded as it began breaking in half.

I didn’t care. I was so jacked up on adrenaline and pure wonder that I kept going. And going. And going, tackling harder and harder obstacles. At this point, the Jeep was already on borrowed time. I had a trailer and a Lexus. “Let’s just send it,” I thought. And send it I did.

The Jeep didn’t care. Its motor felt legitimately powerful, the transmission shifted through its gears well. With the absurdly short 5.38 gearing in the axles, the low range gear, and the shirt first gear, the machine was an unstoppable warrior, climbing impossibly steep grades with confidence.

It even tugged Zac’s Land Cruiser (which was a beast) out of a bind:

Every now and then, the FC would die. Either the ignition cable would fall off the battery, or — and this was more common — the carb would run out of fuel. I’d have to pull the hose out of the carb, use the hand pump to siphon the gas, put my finger over the end of the tube, and then quickly shove it onto the carb as gasoline poured all over my hand. Then I’d have to hop and out touch the jumper cables to the battery in the bed, and the Jeep would fire back up.

Other than these admittedly frequent disruptions, the Jeep left Zac and me in total awe. How was this even happening? Hour in and hour out, it climbed, articulated, groaned, spun its wheels, dragged its rear bumper, but it never ever gave up.

Staring through that cracked windshield, listening to horrific mechanical sounds coming from below, I was having the time of my life:

Seven straight hours. That’s how long the Jeep off-roaded through the trails of Wild Bill off-road park in Montana. It cut off a few times due to fuel starvation and wiring issues, but by and large, it absolutely crushed off-road, exceeding Zac and my wildest expectations.

Why?

I’d put myself through three weeks of hell since boarding that Amtrak bound for Chicago. Sleeping in an SUV in cold weather, getting rust in my eyes, dealing with literal trenchfoot, sucking up the cuts and scrapes, spending lots of money (some of which Jalopnik later reimbursed), and fending off a boss who wondered what the hell I was up to. I even bought a Lexus.

But why?

For one, I love Jeeps, and certain models I simply cannot afford unless they’re garbage. With this FC, I got to feel the experience of driving a Forward Control without having to drop $15,000.

But the overarching reason for this trip was the challenge. I love solving technical problems, I love Jeeps, I love storytelling, and more than anything, I love meeting people.

I could have just bought a nice Jeep in Washington, or simply off-roaded the Lexus. But I bought a hopeless Forward Control and put everything I had into trying to revive it. In the process, I learned so much about vehicle repair; I learned about my ability to get things done come hell or high water; I forged great relationships with people like Tom, Jay, Phil, and Zac; and enjoyed the thrill of defeating Goliath with a genuine underdog.

There are few feelings greater than that.