It was the fall of 2020, and I was galavanting around Europe in a rare diesel manual Chrysler minivan that I had bought for 500 Euros. I had just driven 1,000 miles from Nürnberg, Germany to the middle of nowhere, Sweden, and I had a Germany-bound ferry to catch in the morning. Unfortunately, I had stopped to work, and my laptop had drained the vehicle’s battery. I was stuck.

This all came just after I’d fixed my 250,000 mile minivan, limped it through Germany’s rigorous TÜV inspection, and then taken it on an awesome 500-mile journey. That trip took me to Frankfürt, Germany; Ghent, Belgium; and then to the garage of the Chrysler Voyager King of Germany in Aachen, Germany. The van had performed flawlessly, but given how much time my friends and I had sunken into getting it through TÜV, I was set on putting our handiwork through a more grueling test.

Most of Germany’s surrounding countries — including Belgium, which is where I’d just returned from a week prior — were now considered by Germany’s Robert Koch Institute “Risikogebiete,” or risk regions that would require me to quarantine upon reentry into Germany. As I didn’t want to waste 10 days locked in a house, I chose one of the few remaining countries not on the Risikogebiet list: Sweden.

Sweden at the time was receiving quite a bit of flak from other E.U. member states, as the Scandinavian nation forewent lockdowns in favor of a much more lax strategy, which I’ll allow Arash Heydarian Pashakhanlou, an associate War Studies professor at the Swedish Defense University, to summarize via his report from the World Medical & Health Policy journal:

Sweden pursued a rather unique strategy in tackling the coronavirus pandemic. It allowed bars, restaurants, schools, and shops to stay open when most Western countries opted for a lockdown. According to Oxford’s Government Stringency Index, Sweden had the most lenient COVID-19 policy possible with a score of zero up until March 8, 2020 (Hale et al., 2020).1 This approach received both international praise and criticism. Dr. Mike Ryan, director of the World Health Organization (WHO), stated that “if we are to reach a ‘new normal’, in many ways Sweden represents a future model” (Russell, 2020). Conversely, the former President of the United States, Donald Trump, tweeted that “despite reports to the contrary, Sweden is paying heavily for its decision not to lockdown. As of today (April 30, 2020), 2462 people have died there, a much higher number than the neighboring countries of Norway (207), Finland (206), or Denmark (443)” (Bowden, 2020).

But I wasn’t heading to Sweden to take advantage of that lax COVID strategy, I was headed there for several other reasons. First, as I mentioned before, Sweden was one of few non-Risikogebiet nations (inadequate testing may have contributed to low COVID figures that Robert Koch had to base its assessment on), meaning I could stretch my van’s legs there. Second, I wanted to visit Swedish supercar company Koenigsegg (definitely read that article on that visit, because it was wild). And third, I’d been invited to meet an old friend in Gothenburg and a reader had invited me to his abode way up north.

You can learn about the Koenigsegg visit and the meeting with my old Chrysler engineering friend in Gothenburg in the aforementioned article. After those trips, I headed way up north, but not before finding a junkyard filled with one of the most fascinating Canadian military vehicles I’d ever seen.

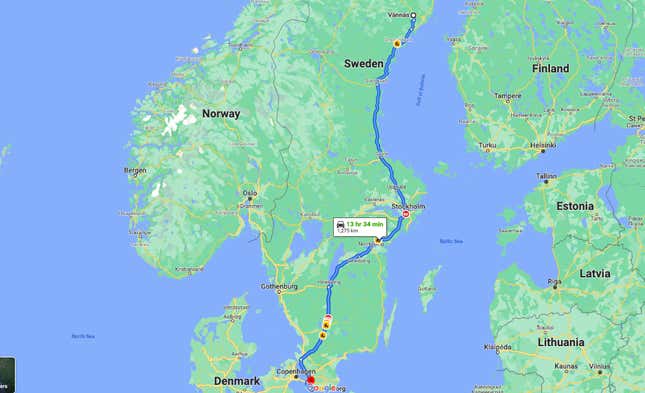

When I was done spending far too much time ogling at war trucks, I hit the road. I had roughly 1,000 kilometers between Gothenburg and the reader named James who had (most likely jokingly) invited me to his place in Vännäs, not far from where he teaches at a university.

Once I’m done conducting a bit more research, I’ll write more about my time with James, who introduced me to fascinating car culture near his and his wife Amanda’s amazing homestead in rural Sweden. Until then, let’s skip ahead to my departure from Vännäs headed southbound towards Germany:

I’d just spent two fantastic nights in a beautiful cabin out in the country, chatting about life with a professor from England and his wife from Minnesota. I’ll recount those nights in my next article, but I’ll just say that there was wine involved, and as a lightweight, this means there was a groggy subsequent morning involved. This was not optimal, because I had a long day ahead.

Stranded In Sweden, Saved By Sketchy Electric Bicycle Batteries

Vännäs really is way up north. I have no doubt that James’s initial invitation for me to join him at 64 degrees north latitude was made at least somewhat in jest, but it was met by a man eager to put Project Krassler, his rare diesel manual Chrysler minivan, to the test.

The return journey began rather leisurely. I had booked a ferry across the Baltic Sea back into Germany for the following night, so I had essentially two full days to complete a 13.5-hour drive. There was only one main road for much of the trip, and it ran along the coast of the Gulf of Bothnia and the Baltic Sea. Occasionally I strayed from this road onto smaller ones to catch a glimpse of the countryside and of the shoreline.

It wasn’t uncommon for me to run into cool reminders of Sweden’s rich automotive culture; for example, check out these two motors just sitting in someone’s yard:

And here’s a look at the beach near the highway; you can see some surfers in the second image — brave souls, given that it was 46 degrees Fahrenheit on this late October afternoon:

Here are a few more images from Sweden’s rural eastern seaside:

And here’s all of that in motion picture form, for all of you youngsters who cannot enjoy antiquated static images:

After a few hours of driving, I pulled the van over near an inlet in the Gulf of Bothnia. I had to finish up an article about a man who discovered an incredible assortment of rare FD Mazda RX7 parts; more importantly, my coworker Jason Torchinsky’s son was turning 10 years old, and I had to somehow make him laugh.

Though I am entirely ignorant when it comes to dealing with children (with 13 cars, I am the singlest man on earth), I do know one thing that will make any of them laugh: misery. Particularly, my own.

Luckily, I was just a few yards from a sea filled with certain misery, so I walked along a floating log and “slipped” into ice-cold water. I questioned the move as soon as my legs entered the water, though the value of a laughing 10 year-old is pretty high, so maybe it was a wash:

Anyway, finishing my Mazda RX7 article — and, admittedly, psyching myself up for the arctic plunge shown above — had taken quite a bit of time, and my laptop had been plugged into my van’s cigarette lighter. I should have known this would drain the battery, but I lost track of time, and when I closed my laptop and cranked the key to continue the additional 12 hours towards Germany, I heard only silence. My battery was dead, and I was stuck.

Attempts to push the van were in vain, since the gravel on which I was parked sloped towards the bay. It turns out, pushing even a 3,500 pound vehicle up even the slightest incline just isn’t possible, especially if you’ve got the muscles of a blogger.

As I sat out there in the dark by myself near the beautiful sea, slowly beginning to worry about catching my ferry the following evening (again, I had 12 hours ahead of me still), a fox popped up out of nowhere. And it would not leave me alone.

The fox circled the van and me four or five times. Every time I turned my back, it seemed to get closer and closer. Eventually, I turned around and saw it just six feet away from me; then it poked its head into the open sliding door on the passenger’s side of the van as I fiddled with cables in the driver’s seat. This was one curious fox.

I attempted to barter with the animal. I had a can of tomato sauce-covered fish in my van, so I proposed an exchange: “One fish for some help pushing this van.” As you can see in the image above, the fox took me up on this deal; or so I thought.

In my naiveté, I had forgotten that I was dealing with a fox, the slyest of creatures in the animal kingdom. The curious furry dog ate my fish and then scurried off, leaving me to fend for myself. I was pissed.

Short of trying to find someone willing to jumpstart me in the middle of the night in rural Sweden (there were some buildings across the way where perhaps I could have solicited aid), I really didn’t have many options. Then an idea came to me.

A few weeks prior, I’d met a reader named Pieter, who was kind enough to not only house me for a few nights in his house near Ghent, Belgium but also to build me a custom battery pack. A huge fan of electric cars and bicycles, and someone who has road-tripped the entire length of Africa, Pieter is an extremely resourceful man, as he showed me when presenting an auxiliary battery pack made of old bicycle batteries. This, he told me, would be a great thing for me to use to power my electronics while my vehicle was off to avoid draining my van’s battery.

I, a total fool, hadn’t yet hooked the battery up to my vehicle’s charging system, which is why I’d simply used my car’s cigarette lighter to power my laptop. I assumed the battery pack had no charge. But in my desperation on the Swedish roadside, I thought that maybe, just maybe, there was still some juice left in those 18650 lithium-ion cells.

Here’s the thing, though: If you go back and watch Pieter presenting me with his awesome battery pack, he specifically tells me not to use these two wires poking out from it.

“There are also two wires which you should actually never use,” he begins. “These are actually straight to the cells, so if you ever need to jump start your car, which I would not recommend...it notes you shouldn’t use it, but it’s there if you ever need to use it.”

Recalling Pieters words didn’t exactly inspire confidence, but I was out of options. My van was dead, a potentially rabid fox was nipping at my heels, and I had a boat to catch. I was willing to risk frying my vehicle’s entire electrical system to get out of this jam.

I grabbed my miniature toiletry scissors, and cut off some insulation from those two mysterious wires. Then I clamped one end of my jumper cables to them, and the other end of the cables to the battery posts.

I hopped into the car, turned the key, and — as expected — nothing happened. “I bet the battery pack is just dead,” I thought to myself again.

I then walked to the front of the van and jimmied the cables a bit. I noticed that my van’s interior lights got brighter as I shifted the cables. My heart injected a small dose of hope into my bloodstream.

I fiddled with the wires some more until the van’s dome lights remained steady and bright. “Maybe it just had a bad connection?!” I thought again, my circulatory system now pumping large volumes of promise throughout my body.

I turned the key. “Crank!” I heard. Then the engine died as the dome lights dimmed.

As someone who has dealt with far more corroded battery cables than I’d like, I knew this was good news. I ran to the front of the van, tried creating as solid of a connection between the cables and the two batteries as possible, and returned to the driver’s seat. The engine fired right up!

Somehow, the two mysterious wires from that battery pack that a reader named Pieter from Ghent, Belgium had built for me had come in clutch, saving me from a bind. But time was a problem, as I had a long way to drive before my ferry the following evening.

After having sat in that spot by the sea for over six hours, I only drove an hour or so before having to stop to catch some sleep in the van, which I’d pulled into some woods, but strategically parked on the hill in case my battery hadn’t had time to charge.

When I awoke the following morning, I calculated that I’d have to drive 11.5 of the next 13.5 hours — a hell of a task, especially for someone who’d been sleeping in a cold van.

As you can see in the video above, I powered through. The Chrysler Voyager, scoring over 30 MPG the whole way doing roughly 65 to 70 MPH, rode smoothly over Sweden’s well-maintained roads. The new shocks that I’d installed, along with the fresh rear leaf spring shackle bushings aided in keeping the van floating over the surface, while the couch-like seats coddled my fatigued body.

Visibility through the front windshield was great, the diesel engine hummed efficiently under the hood, and that manual gearshift remained lodged in fifth for pretty much the whole duration. Wearing its shiny new German TÜV inspection sticker with pride, the van was flawless.

It reached the ship with time to spare, and though I felt beaten down, I knew it could have been much worse had I been driving a less comfortable cruiser.

I slowly climbed up the ramp in first gear, and filed into the hull of the big ship with the other cars. A beautiful green Morgan pulled in behind me and parked:

Over seven hours later, I was in northern Germany descending a ramp into a town called Rostock.

I was concerned that Sweden would be put on the Risikogebiet list, and that I’d have trouble entering Germany, but I showed my red passport, and drove right in.

The Nazi Ruins At Prora

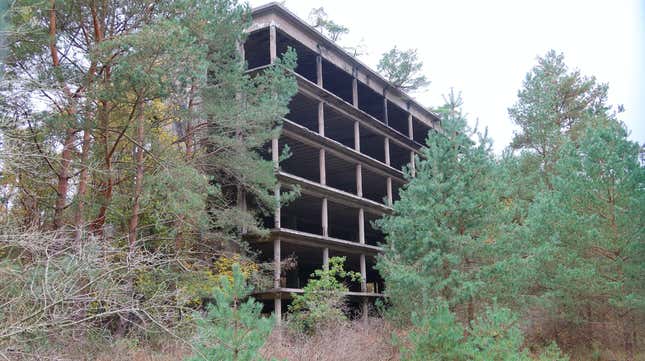

Before heading back to my parents’ place near Nürnberg, I headed east to the island of Rügen, where I’d been invited by a reader. I met him, and also checked out a fascinating bit of German history: the Colossus of Prora — a huge group of buildings with perhaps the most badass name I’ve ever heard.

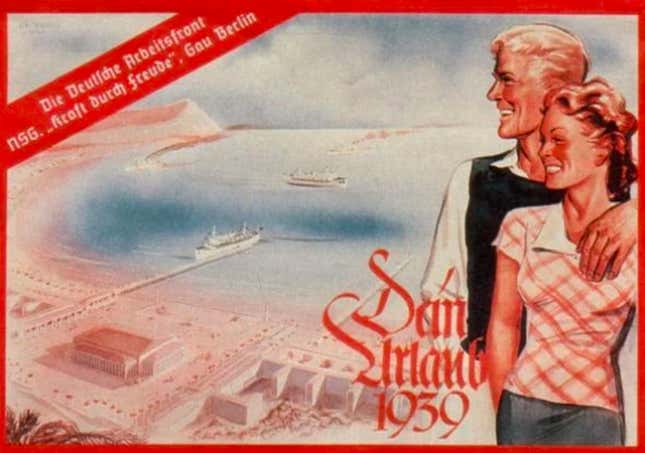

The structures were erected in the 1930s as part of the Nazis’ “Kraft Durch Freude” program, which translates to “Strength Through Joy.” The initiative, also referred to simply as KDF, was a leisure program meant to facilitate R&R and just generally promote a high quality of life among Germans.

German state-owned media company Deutsche Welle describes this fascinating wonder in its recent article about its partial-restoration, writing:

It was built on the orders of Adolf Hitler in the 1930s, according to the designs of a Nazi architect, Clemens Klotz — whose surname actually means block. The manic aim: 20,000 people at a time were to vacation in the nearly five kilometer-long (3.1 mi) holiday camp, arranged by the Nazi “Kraft durch Freude” (Strength through Joy) organization, known as the KdF for short. Its mission was to control and bring into line the German population’s leisure time. All 10,000 rooms were to have a sea view, which explains the gigantic length of the structure.

The article continues:

A monument to megalomania

Prora perfectly represents the Nazi regime’s megalomania — and its incompetence. When the regime instigated the Second World War in 1939, construction was discontinued. The complex was never completed. No KdF tourist ever vacationed in the “seaside resort for twenty thousand”. Instead, the housing blocks, which were shells, were used militarily — as barracks, for instance, first under the Nazi regime, and then in communist East Germany, the GDR. After the Berlin Wall fell and Germany was reunited, the complex was officially historically listed. Museums and artists’ studios moved in, but large sections of the monstrous structure, considered the longest of its kind in the world, decayed.

The building is absolutely gargantuan, per the orders of Adolf Hitler himself, who specifically wanted a seaside resort for German workers — one that would dwarf anything of its kind anywhere in the world.

Neither my video near the top of this article, nor my photos capture how enormous this structure is, so check out this fantastic German documentary to get an idea of the staggering scale:

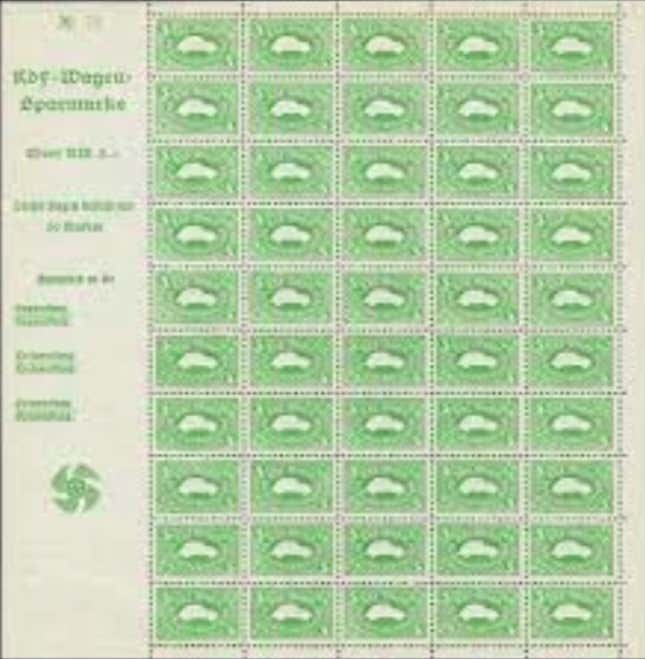

The whole KDF program was a bit absurd. It was responsible for the creation of the Volkswagen Beetle, which was originally called the “KDF Wagen.”

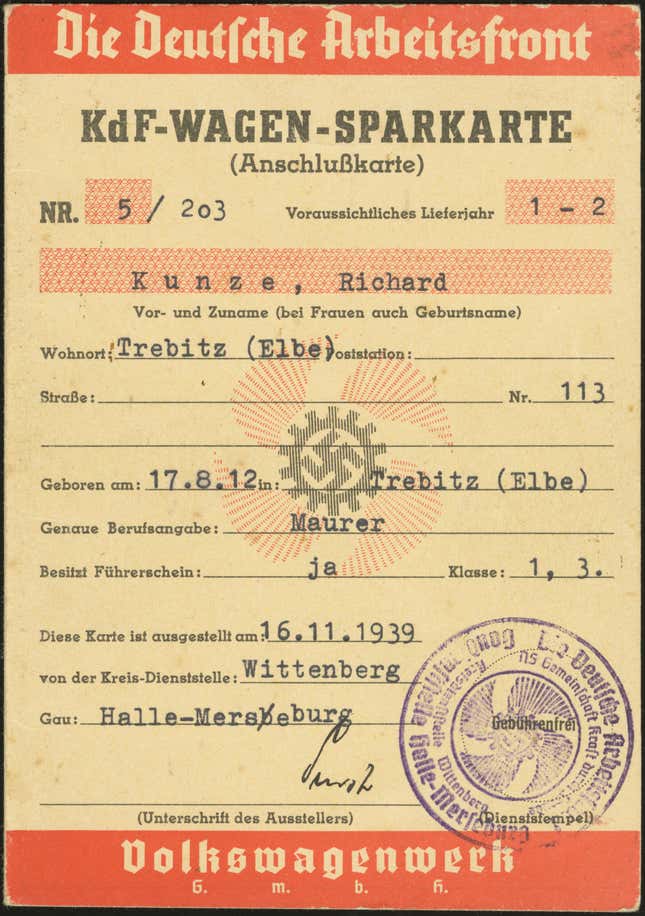

Like Prora, the vehicle was one meant for the people (“Volks”). Specifically, it was there to get the masses mobile and driving on the newly-established Autobahn. During World War II, the Nazis sold the stamps you see above as part of a savings program. People would buy those stamps, and insert them into a booklet called the KdF-Wagen-Sparkart (or KDF Car Savings Booklet):

As my coworker Jason Torchinsky wrote in his excellent article “The Real Story Behind The Nazis And Volkswagen,” the whole thing was a scam. Even though the Nazi’s did commission Ferdinand Porsche to develop the Beetle, and they did erect a manufacturing town called “Stadt des KdF-Wagens bei Fallersleben” (which means “City of the KdF Car at Fallersleben” and is now known as VW’s home city of Wolfsburg), none of the hundreds of thousands of people who bought into the KDF Program’s savings-scheme ever received a car.

Like the Volkswagen program, Prora was ultimately another KDF-sponsored disappointment. After being constructed before the war, it sat empty for years. As Deutsche Welle mentioned, the massive structure saw use in military applications, but it wasn’t until recently that it started to see a more significant restoration into apartment buildings and even a large youth hostel. Have a look:

So that’s pretty much where things stand at Prora. There are some nice apartments, a nice youth hostel, a slew of promising plans, and more square-feet of abandoned structure than I’ve ever seen outside of Detroit’s Packard plant.

But of course, Rügen is more than just Prora, it’s quite a popular vacation spot filled with breathtaking views. I parked my van near a field, and went on a small hike to see the famous Victoria View below:

Here’s another look:

After a nice day on the island, I crashed in the van for the night, and then hit the Autobahn.

After a 3,000 mile trek to the most northernly point I’d ever been, and after seeing some incredible Nazi ruins, my unstoppable $600 minivan drove me back to my parents’ place near Nüernberg, confidently. It was at this point that I knew that the van was ready for an even more difficult challenge.