My 250,000-Mile Chrysler Minivan's First Test Since The German Inspection Was A 500-Mile Trek To Belgium

A few weeks ago, the 250,000-mile diesel manual Chrysler Voyager that I'd bought sight unseen for $600 narrowly squeezed through Germany's absurdly strict safety inspection. But as trying as that ordeal was, to really learn what my van was made of, I had to hit the road. So that's what I did, pointing "Project Krassler" west from Nürnberg towards Ghent, Belgium 500 miles away.

Buying a car sight unseen on another continent is a huge risk. In addition to the $600 I dropped on the glorious 1994 Chrysler Voyager turbodiesel, I also spent $500 on a flight to Germany and a bunch of cash on Airbnb lodging. Add to that the price of all the replacement parts, plus vehicle inspection fees, car insurance, and garage rental costs, as well as over a month of my time, and you get the idea that my dream of living the van life in Europe in this obscure diesel manual Chrysler was a big risk. Particularly because I didn't even know if the Voyager, which didn't run when I bought it, could even be brought back to life.

I have to say that, roughly 40 days into wrenching on the van, there was a moment when I wondered if the whole operation was going to be a huge waste. I had pumped so much time and so many new parts into the machine, and I hadn't even driven it. When I piloted the van to an official TÜV inspection station, and it passed — admittedly only narrowly and after three attempts — my confidence grew. The dream no longer felt distant; it felt achievable.

It felt even more achievable after I'd (arduously) replaced my water pump and accessory belts, and — with new license plates screwed to my bumpers — drove over 60 miles to my parents' house without issue:

But then it was time for an extended trip.

I'd searched through my emails and Instagram messages, and made a list of scores of kind readers around Europe who had invited me to their abodes. On that list was Pieter, a man from Ghent, Belgium, who told me he'd built me a battery pack so that I could charge my laptop and phone without draining the van's battery while I slept. I decided I'd visit him first.

Also on my list was Doug, a Jeep Cherokee owner working in Frankfurt. I figured I may as well visit him, since he was on the way. My parents had told me that they were interested in visiting Düsseldorf and Köln, two cities also on the way to Ghent, so I decided the three of us would drive together, even though I realized that it was a bit risky taking my parents on the Autobahn in a $600 machine that I'd only driven 75 miles in total.

If this Austria-built, Italy-sold, and USA-engineered diesel, manual Chrysler minivan was going to fail, it was going to take more than just me down with it.

Nürnberg To Frankfurt

My initial vision for this van trip involved building sleeping quarters inside the van. I even drew up some plans for an elevated wood platform with pull-out drawers, a wall for mounting things, and a board lining the ceiling to allow for hanging of certain items that I'd planned to purchase along the way. I still hope to construct such a setup in the van sometime in the future, but I simply ran out of time.

Germany's coronavirus restrictions were growing ever-stricter by the day, and with more countries entering the Robert Koch Institute's list of risk areas (Risikogebiete) I was running out of places I could visit without having to quarantine upon my return.

So instead of fashioning the van into an apartment, I simply removed the heavy rear bench and one of the middle captain's chairs, threw in an air mattress and sleeping bag, filled some bags with food and clothing, and prepared to head west.

With my mom in the passenger's seat and my dad sitting behind her, I turned the key and listened to the VM Motori 2.5-liter turbodiesel fire to life. While cold, one of the accessory pulleys squeaked and the top-end of the motor made a loud woodpecker sound from the valvetrain. After I waited a minute for the oil to circulate and that pulley to warm up, the Chrysler quieted down and was ready to head to the Autobahn.

With brand new tires, freshly-replaced tie rod ends and ball joints, new rear leaf spring bushings, new sway bar bushings, shiny rear shocks and a recent alignment, Project Krassler drove perfectly. My parents were as impressed as I was with how smooth the ride was, how composed and confident the vehicle felt as it piloted down Germany's fast-paced roadways, and also how incredibly comfortable those overstuffed cloth seats were.

Aside from a few rattles caused by mixing questionable Chrysler interior build quality with the harshness of a diesel engine often used in marine applications (we fixed some of the rattles by placing heavy objects on the dashboard) and some wind noise caused by the four roof rack crossbars (I later removed two, and it quieted things down) the Voyager's cabin was quiet, even at 80 mph.

I didn't dare eclipse 80, though, as the vehicle's short axle ratio, combined with its tiny 205 70R15 tires meant engine speed at 80 was between 2,500 and 3,000 rpm. And while that may not sound like much, remember that this is a diesel, and revving an ancient compression-ignition engine anywhere above 2,500 rpm for a sustained duration just goes against the laws of nature. The vibrations, the noise; something about it just isn't right and what's more, it feels wasteful, since all that diesel-y torque means the motor makes enough power at 1,500 RPM to easily move the van along at 80 mph.

The five-speed shifter, whose bushings I'd replaced and whose shift linkage I had fabricated from steel bars, felt perfect. It was smooth but notchy enough to feel satisfying going into gear. The clutch pedal, with its short travel, felt nice and stiff, though while depressed, it did yield a bit of grinding noise from the throwout bearing when cold.

It's a weird sensation driving this old K-car based minivan. It's obvious that Chrysler took a car platform, added a tall-roofed body to it, and mounted the seats way up high so that the driver's H-point (a term used in car design denoting the hip location) feels almost at the same height as if I were jogging down the roadway.

This high seating position is one of the key elements that distinguished these early minivans from the wagons that preceded them as the go-to family haulers in the U.S., and I totally understand why. With my van's relatively short hood, its high seating position, and the small pillars making way for an airy, huge glass greenhouse, I had a great view of the road. And I can see how that made early minivan adopters feel confident and safe.

After a few hours of musing in wonderment at this van and chatting with my parents about what's next for all of us, I dropped my parents off at the Frankfurt train station and I headed to meet Doug.

Doug In Frankfurt, Germany

"Coming to Germany?" reads the subject line of Doug's July email to me, in which he wished me well in my race to meet my city's order to fix my dilapidated fleet. Doug has been a long-time Jeep fan, so we chatted back and forth about his 1995 Cherokee, whose carpet he had recently stripped to tend to some floorboard rust:

Doug invited me to visit his home in Frankfurt, so that's where I headed before planning to reconvene with my parents in Düsseldorf, a cool city on the Rhine River known for art, fashion, and tech industries.

Doug showed me around his beautiful Canadian Jeep (odd, since Jeep sold XJs in Germany), pointing out its gorgeous tan interior, mighty four-liter engine, and largely rust-free body. He also highlighted the vehicle's custom license plate: "XJ" for Jeep XJ and "215" for his hometown area code. Such custom plates, Doug told me, are commonplace in the country. The first few letters represent the town of residence, and cannot be altered. But car owners can pick out the next two letters and following three numbers free of charge, so that's what many Germans do.

Doug then showed off his awesome bicycle collection, including electric bicycles (which he converted himself) and souped-up scooters.

After meeting car enthusiasts around the world, it's become clear to me that bikes, scooters, and e-bikes are the "project cars" of folks who a) Live in a city where parking cars is difficult b) Have a family that demands time and a spouse who maybe doesn't approve of purchasing lots of cars and c) Have to pay hefty vehicle taxes and steep fuel prices.

Ultimately, folks like Doug have a wrenching "itch" that they have to scratch, and if they were like me, living out in the open in the U.S. with few responsibilities, I'm certain they'd probably hoard cars; as they live more "civilized" lives, bicycles it is.

Seriously, listen to Doug's rundown of his bike collection. It should be clear that just because he doesn't have the city coming after him, he's still plagued by whatever disease I have:

1963 Huffy Sportsman (originally my grandmother's)

1983 Peugeot P6 Iseran (purchased new by my dad)

24" Hercules kids bike

1980 Peugeot C46 (kids bike)

2015 Prophete 2-S converted into a 750 W e-Bike

Late 80's / early 90's Peugeot PE11DW (with an odd 24" front wheel and 28" rear wheel combination)

Another cheap 24" kids bike

2017 NIU N1S

1999 Aprilia Habana 50

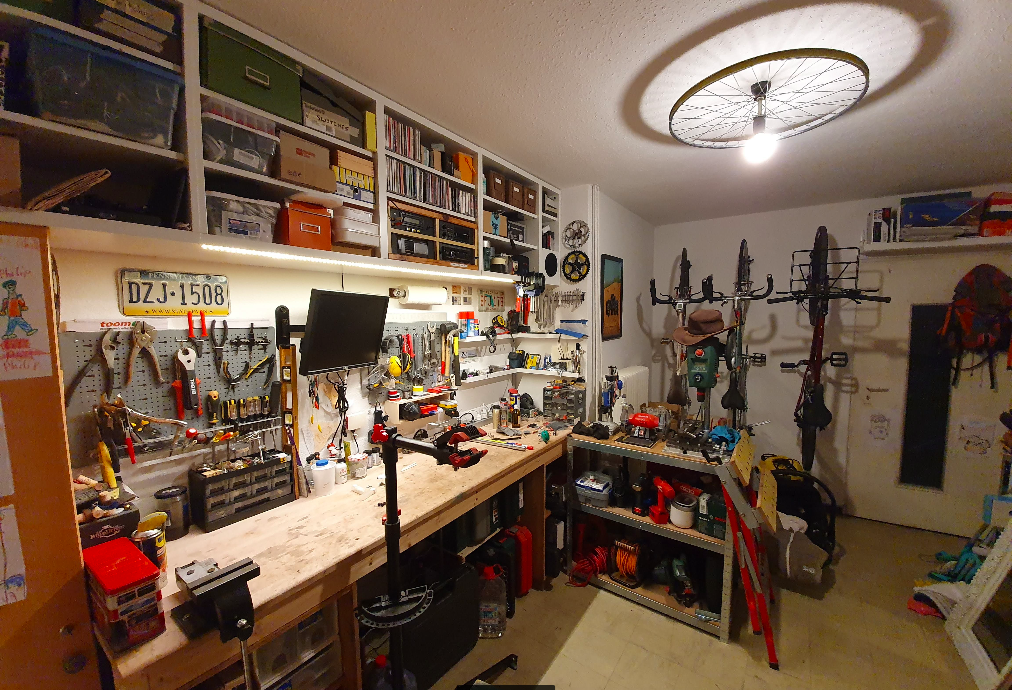

In my workshop, I have (left to right):

1985 Willi Müller (purchased new by my father-in-law)

1986 Peugeot PH501 (converted to single speed)

2021 Bombtrack Arise Geared (purchased this past Saturday)

I also have three other bikes at my office, including a Miele from the mid-1930's, a mid-70's Peugeot 3-speed, and a 1992 Peugeot with a 2-speed automatic hub. So that's 9 adult bikes (I was up to 13 at one point), 1 teenager-sized bike, 3 kids bikes, 2 scooters, and 3 cars (1995 Jeep Cherokee, 2013 Mercedes E300 kombi, 2016 Seat León). It's good to have options. :-)

After Doug drove my van and at least pretended to enjoy himself in a vehicle that most people probably think is the least cool car, possibly ever, I piloted his Cherokee over to a car-haven called Klassikstadt. The place is filled with beautiful old cars, some for sale, some just being stored by wealthy owners, and many hanging around as backdrops for weddings and other events that can be held in the big hall for a fee.

Doug and I stared at old Mercedes-Benzes and Jaguar E-Types, eventually sitting down in a restaurant on the premises. There, I learned that Doug has lived a hell of a life. First, let's talk about his cars.

His first car was a 1990 Plymouth Sundance, which is actually based on the same K-car platform that underpins my van. While studying engineering a Virginia Tech, Doug drove the white 1995 Jeep Cherokee you see above, and later bought a green 1992 with over 220,000 miles on its odometer. In 2003, he did an epic road trip in a then-new Mini Cooper, and later, his Grandmother in New York gave him a beautiful 1972 Mercedes 220.

With the cars out of the way, let's talk about the "inflection point." As I traveled through Europe and met ex-pats, I found that nearly all of them could point to a singular moment when they just had to make a drastic change. In Doug's case, this moment occurred 2.5 years after college, while he was working for a highway general contractor in Pennsylvania. Doug did that cross-country road trip in the Mini shown above and then flew to Australia, a place he'd never been, to attend graduate school.

It's in Australia that he met his wife, Britta. After a short time down under, the two of them moved to England, where Doug — a civil engineer — worked on the Channel Tunnel Rail Link Project (a high-speed line that links London with the Channel Tunnel); he told me a story about how he biked over 10 miles through those tunnels before the tracks were laid. That must have been epic.

After 14 months in England, he and Britta moved back to Australia, then to Hong Kong, then to New York, and now they live in Frankfurt.

Upon returning from Klassikstadt, I hung out with Doug's hilarious bilingual children, who were beyond excited to show me their legos (and I was equally excited to see them if I'm honest). I sat with the family as we ate Bratwurst, salted potatoes, spinach puffs, salad, and a brownie. I remember the meal vividly because it was excellent.

Düsseldorf and Köln With My Parents

I left Doug's place on Saturday evening, and shortly thereafter fell asleep in Project Krassler at an Autobahn rest stop before eventually meeting my parents at their hotel early in the morning. The three of us spent the next day touring the beautiful city of Düsseldorf.

I won't delve into it too deep, since this is a car website and not a travel blog, but check out these Frank Gehry buildings:

More importantly, how about the awesome, covered, wood-paneled Piaggio Ape out front?:

Also, there were boats:

And there was some excellent artwork by Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and other painting legends:

From Düsseldorf, we took a train to Köln to see the cathedral. That was awe-inspiring — almost as awe-inspiring as the chassis of the little tour train out front:

The next morning on Monday, my parents and I parted ways, with me heading northwest to Belgium.

Just before entering the country, I spotted an EU-spec Blazer that totally blew my mind, and ultimately sent me down a rabbit hole that yielded a ridiculously long article about second-gen Chevy Blazers:

Having driven over 300 miles to Düsseldorf, I crossed the border into Belgium and completed the final 200 miles to Ghent. On the way, I spent nearly $100 filling up Project Krassler at a cost of roughly $5 per gallon of diesel. Yikes.

I divided the trip computer reading by the pump's fluid volume readout, and calculated that my diesel, manual Chrysler Voyager had scored over 31 mpg! That's incredible for a seven-passenger machine, and a figure that's literally double the fuel economy of many of my vehicles in the U.S.

Since the fuel price is roughly double, I basically paid the same amount per mile to drive the fuel-sipping van in Europe as I do to drive my guzzling trucks in the U.S.

Pieter And Ezra In Ghent, Belgium

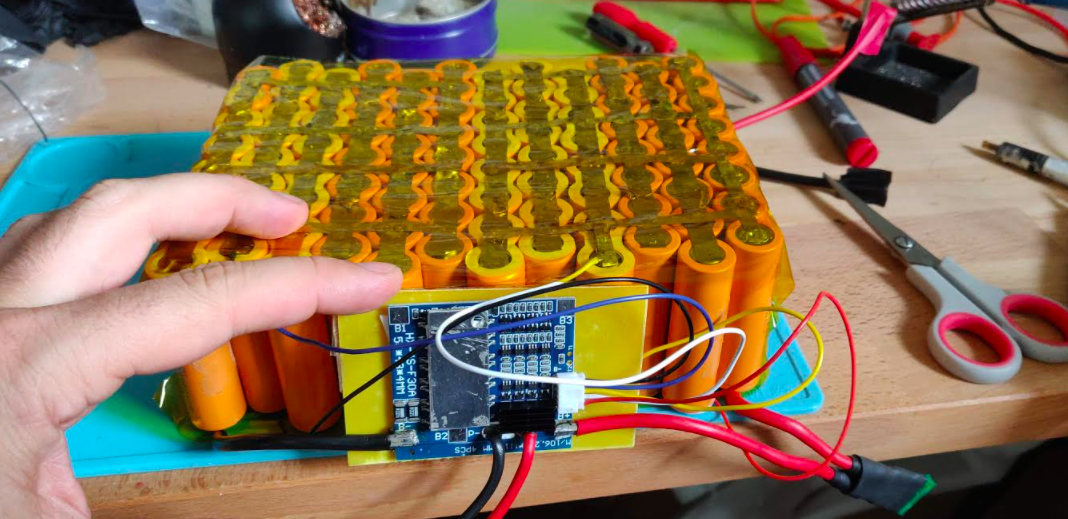

I arrived in Ghent on Sunday morning and met up with Pieter, an innovation consultant and a huge fan of electric vehicles (especially bikes). In fact, that battery pack you see Pieter holding above is made of old electric bicycle battery cells. Check out the guts:

There are two wires in the pack that Pieter specifically warned me not to use unless there is an emergency. These wires, as you will read in an upcoming installment of my Project Krassler series, came in clutch when I was in a bit of a bind in the middle of nowhere, Sweden. (Again, more on that later).

Where Pieter and I really bonded was our shared sense of adventure. When he was my age, he took a six-month trip down the entire length of Africa in a Toyota Hilux. It's a trip that I myself have been discussing for over a year, and to hear Pieter's experience makes it seem all the more feasible.

We sat there in his house in a small town outside of Ghent looking at incredible photos from his trip six years ago. He walked me through some of the ordeals he faced, and some of the triumphs he enjoyed. It was a captivating story, and one that I hope to soon have my own version of. Here are a few photos from his excursion, starting with a Peugeot 404 pickup laden with fish:

Later that night, Pieter and I met with a Land Rover/BMW fan named Ezra in downtown Ghent, where I experienced the joy that is Belgian fries. Covered in meat sauce and mayonnaise, they are a delicacy, and a reminder that French fries are actually not French. The Belgiums are the experts in the field of greasy potato sticks; let no one tell you otherwise.

From the fry spot, the three of us ogled at this beautiful Citroen DS:

Then we headed to a mostly-empty bar, and drank Belgian beer. I normally don't drink beer, but given that I was in Belgium sitting with two beer aficionados, it seemed only right to try. (It was disgusting, of course, but in a way that I could appreciate).

"Hey, want to get a tour of a giant building?" Pieter asked us, my buzz already well underway thanks to the heavy beer. "Uh, sure?" I answered.

The three of us left the bar, and Pieter and I began a long walk across Ghent in the middle of the rainy night as Ezra headed to his car to drive the couple of kilometers.

Just after we left the bar, the two Belgians and I came upon a Land Rover with no rear seats. A Land Rover fan (that's his above), Ezra told us about the concept of "Utility Spec." It's a way for Belgians to save thousands of Euros per year on taxes by simply removing the rear seats from their vehicles, effectively turning those vehicles into vans. "That's why most old Land Rovers [and other SUVs] you see here have no rear seats," Ezra told me.

It's a fascinating loophole.

The walk from the bar to the mystery building is one I'll never forget. Pieter tried his best to act as a tour guide, though most of the time when I asked what we were looking at, it was clear he was guessing. Still, the sights were gorgeous:

After that beautiful walk through town, Ezra, Pieter, Pieter's friend (the building manager) and I found ourselves atop a famous building called Vooruit. Here's the view:

The building is basically an arts building for the people of Ghent, having started as the headquarters of the city's labor movement in the early 1900s and as ground zero for the socialist push. Nowadays, it's used as an event space, often for techno concerts.

The building is absurdly huge, and its many passageways and stairwells would make it damn near impossible for a first-timer to navigate without a guide.

It was a strange moment, me buzzed on Belgian beer walking through this beautiful, confusing Belgian building in the middle of the night with the building manager and two people whom I barely knew, but felt I had become instant friends with thanks to our shared love for cars.

From the rooftop, we could see the Winter Circus building, which, as Ezra and Pieter noted, used to be filled with cars:

Inside Vooruit, we saw beautiful concert halls and event spaces:

On the ground floor of the building was a bar, where the four of us — for reasons unknown — drank more alcohol before we all retired for the night.

The next morning, prior to my departure, Pieter and I took a cruise in Project Krassler through the beautiful Belgian countryside.

The van impressed him, just as it continues to impress me. Once warm, the engine sounds perfect (for a diesel), the transmission shifts like new, the ride is smooth, and the steering is tight. All the buttons on the interior work, the seats and carpets look great, the exterior looks decent; I could go on and on.

Somehow this 25 year old, 250,000 mile, $600 van drives like a vehicle half its age and mileage. The trusty family hauler had completed 500 miles to see Doug and his family in Frankfurt, to check out Düsseldorf and Köln with my parents, and to drunkenly tour the beautiful city of Ghent with Pieter and Ezra.

My next stop was the city of Aachen, where I had arranged to meet with Tizian, the 26-year-old Chrysler Voyager King. He's a man whose love of Chrysler minivans is simply beyond comprehension. He started the Chrysler Voyager online message board in Germany, he has dozens of official Chrysler Voyager reference books on quick-draw, he can recite model year changes, he knows all about the rare versions of the Voyager, and he can walk you through how the all-wheel-drive system works.

His passion is palpable, and he truly has an encyclopedic knowledge of second-gen Chrysler minivans. The fact that such a young, minivan-loving German like him exists is already amazing. Add the fact that he does all his work in a fascinating, cold, dark, broken building formerly used as a textile mill, and Tizian's story becomes even more compelling.

So keep an eye out on Jalopnik for the next installment of Project Krassler, because you're not going to want to miss it.

As I drove from Ghent to meet Tizian in Aachen, I felt for the first time genuine relief. All that risk I had taken on by purchasing a non-running $600 van located on a different continent, by dropping all that money on a flight, by spending over a month prepping the vehicle, and by sinking hundreds of dollars of parts into a van I'd never even driven, seemed to have paid off. I was living the van-life, cruising comfortably and efficiently through beautiful parts of Europe, meeting fascinating people, learning awesome things about car culture, and quickly falling in love with the minivan of my dreams: a 1994 diesel, manual Chrysler Voyager. Project Krassler.