I think there’s at least two things Soichiro Honda and I have in common: we both can really rock a good jumpsuit, and we both love air-cooling, perhaps irrationally. The car I want to talk to you about today has nothing to do with Honda, but old Soichiro always comes to mind when I think about air-cooled engines. Maybe that’s just me. By far the most common and best-known air-cooled car is the original Volkswagen Beetle, and I’ve often wondered about if VW ever experimented with water-cooled engines in the old-school Beetle. They had, and I recently learned about one experiment I never knew about, so let’s explore it together.

Air-cooling was an important hallmark of the original Beetle. The flat-four engine design, with its big cooling fan and finned cylinders resembled an aircraft engine of the era more than a car engine, in many ways.

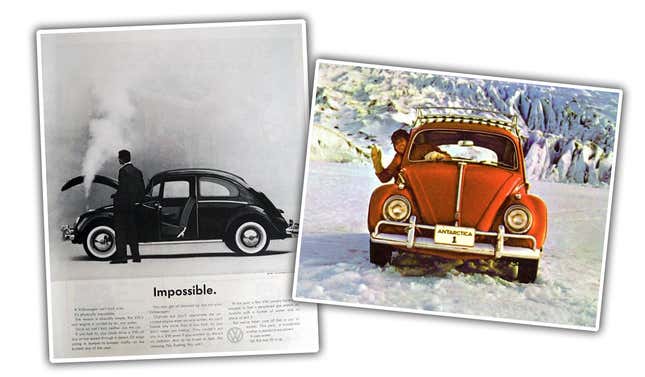

When the Beetle was designed, and into its days of rapid growth and sales in the 1950s and 1960s, air-cooling provided some real advantages over the less-sophisticated liquid cooling systems of the era: It couldn’t overheat and boil over or freeze up in the winter.

Of course, these qualities were played up heavily in VW’s advertising, and the lack of any sort of radiator became one of the defining traits of the Beetle, so much so that in CB radio slang “hauling Volkswagen radiators” was how a trucker could say they were hauling an empty trailer.

Over time, coolants became better and better, and the advantages of an air-cooled engine over a liquid-cooled one became less and less pronounced. Plus, air-cooled engines tend to be louder and, more importantly, have more difficulty meeting strict emissions standards, which were becoming significantly stricter by the 1980s.

Volkswagen was switching to water-cooled designs in the 1970s, and while the Beetle stopped being sold in America by 1980, it was still sold in Europe and was built and sold extensively in Brazil and Mexico. While these markets still used the old air-cooled design, it makes sense that VW would look into adapting the Beetle to the water-cooled engines the company was standardizing on its other models.

I knew about one strange attempt to do this by VW from 1985, when they cut a VW Bus Wasserboxer (a liquid-cooled version of the Type 4 air-cooled engine used in Vanagons) engine in half and installed it in a Mexican Beetle.

This flat-twin Beetle was really, really strange, and had a bonkers swing-out radiator mounted at the rear of the engine compartment. The half-a-motor only made about 34 horsepower, which was a good drop down from the Beetles of that era, and the project never really went anywhere — it would have taken too much work for too little payoff.

Volkswagen’s other attempt to adapt the Beetle to liquid-cooling actually happened a year before the half-Wasserboxer one, and it was much, much more practical. I can’t believe I had not heard of it before, especially because the prototype actually exists, and is at a museum I’ve visited before: the Volkswagen Foundation Museum in Wolfsburg, Germany.

This car was not on display when I visited years ago, otherwise I’d absolutely have remembered it. I have to thank auto savant and Renault 4-loving autojournalist Ronan Glon for clueing me into this remarkable refugee of a timeline that never happened, the Beetle with the VW Polo engine.

This fascinating beast is a 1984 Mexican-built VW Type 1 Beetle with an EA111v water-cooled, 1043cc inline-four engine, the kind VW was fitting to small hatchbacks like the Polo.

The Polo engine made 45 hp, about on par with ‘80s-era Mexican built Beetles, a bit less than the Brazilian sugar cane alcohol Beetles, but good enough to give the Beetle a top speed of 82 mph, which is one better than what the owner’s manual for my old ‘71 Super Beetle, which had a dual-port 1600cc engine making a claimed 60 hp, could do.

The way this engine was crammed into the Beetle’s engine bay is fascinating; let’s get a closer look. Computer! Zoom and enhance!

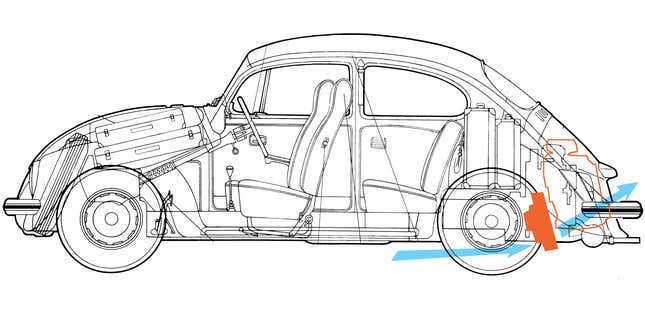

The engine is mounted longitudinally, with the exhaust manifold on the right side of the car there — well, when viewed from the rear, as in this picture.

The length of the engine seems to fit surprisingly well in there, though that crank pulley is pretty tight at the bottom. What you may be noticing is the absence of a pretty crucial component, arguably the one that is at the core of why this experiment was even tried: The radiator.

There is what looks to be a radiator on the lower left there, surrounded by an air intake (I think actually exhaust?) hood, and the engine lid has been modified to include ventilation for that area, along with another vent on the other side, perhaps for symmetry:

They also raised the license plate light and housing up a bit, though I’m not really sure why.

The radiator itself, though, isn’t exactly inside the engine compartment; it looks to be mounted underneath the car, at least partially:

It looks like the radiator is mounted to the left and a bit below the engine and pulls air in from underneath the car, then exhausts it through the engine bay and out the little mesh part of the engine lid. It looks like a cooling fan is in front of the radiator to draw in air, too.

My best guess from these pictures is that the setup looked something like this:

The solid orange block is the radiator, to the side of the transaxle, and the blue arrows show expected airflow. It’s sort of a clever packaging solution, only costing a bit of ground clearance, though it likely would have made servicing kind of a nightmare, all packed in there like that.

The whole point of this experiment was to try and find a solution for the Beetle to meet more stringent emissions standards, and I suspect it could have pulled that off, though based on the fact that VW kept building old air-cooled Beetles in Mexico until 2003, I guess they didn’t really have to meet those standards, at least not for another 20 years or so.

Where this experiment did seem to pay off was not with the Beetle, but with its larger, air-cooled sibling, the Type 2 bus.

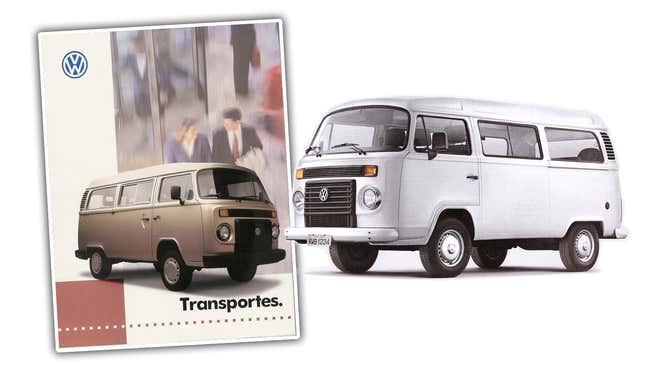

The Bus started with the same sort of horizontally-opposed air-cooled engine as the Beetle, and while the later Vanagon Type 2 buses and vans adapted to water cooling first via the Wasserboxer and then other VW inline water-cooled engines, the older Type 2 buses stayed in production in Mexico and Brazil.

These older-style buses were adapted to use water-cooled, inline engines in 1995, much like this experimental Beetle, but the radiator packaging was much easier, as VW just slapped it on the very front and ran a lot of hose to it:

This solution worked quite well, as water-cooled Kombis and buses stayed in production all the way until 2013.

Could a similar solution have worked for the Beetle? Maybe, but it would have been difficult; perhaps the front end could have been modified to have a radiator in front of the spare tire, but that would have changed the famous look of the Beetle a lot, and by then VW was pretty committed to the Golf and Polo as its primary mass-market economy cars.

I like knowing that VW at least tried, and part of me would have liked a world where old-school Beetles adapted to the times like this, but, for good or bad, that’s not the reality we got.

Parallel universe Torches, please let me know if this played out differently where you are.