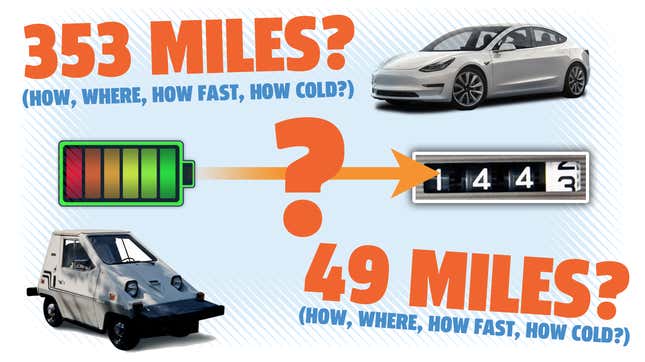

In general, the way we measure how far any car can go on whatever kind of fuel or energy you cram into it is pretty flawed. There are a lot of reasons for this, but a big part of it has to do with the fact that we’re trying to get one or two definitive numbers for something that is definitively variable and sloppy. How many miles you can go on a full tank or charge has an absurd number of variables affecting it. I’ve talked about this for combustion cars before, and now I want to address EVs. So hang on.

EV range is one of the most crucial bits of information consumers look at when choosing an electric car. And it absolutely should be. Since charging an EV, even with the most advanced, high-output chargers out there, takes significantly longer than filling a car up with gas, you have to plan your travel more carefully than most people are used to, and knowing just how far you can go before you have to do that is crucial.

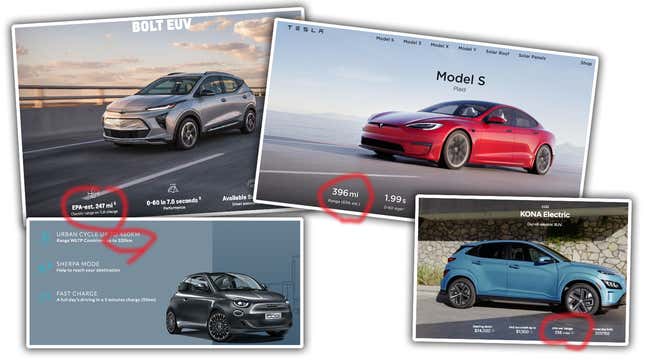

In America, we tend to apply one number for EV range, which is arrived at via EPA testing (based on the SAE J1634_201707 test procedure standards) on a dynamometer that simulates urban, highway, and steady-state driving. These tests are known to be more gentle and accommodating than real-world driving, and as such uses a lot of “adjustment factors” to help make the estimate more realistic.

Even so, there are all kinds of ways to game this system, while still keeping within the rules, and some companies, like Tesla, have proven to be very good at this.

The European WTLP cycle does try to differentiate between urban and non-urban cycles as well, which is good, and WTLP can provide different range estimates for each, but the results are still an estimate and are routinely higher than the cruel real world.

In fact, we just wrote about a recent test by What Car? in the UK that shows just how far off WTLP estimates are from real-world driving, and they’re significantly off, with the Tesla Model 3 falling short of its “official” range number by 76 miles, the Ford Mach-e falling short by 77, the VW ID.3 was short by 38, and the Porsche Taycan by only 9.

Here’s that full video if you’d like to see it:

Okay, so I think all we’ve established here is that overall, the EV ranges given are not terribly accurate, and this is a problem. Range estimate disparities of over 70 miles are not trivial at all that makes planning trips in an EV a pain.

So, what would help?

I think the key here is to accept that EV range will vary dramatically between city driving and highway driving, more so than it does in a combustion car, and that difference is even more important in EVs.

For an EV, city driving provides many opportunities to maximize range, thanks to regenerative braking, generally low speeds, the amount of time stopped in traffic, and so on. Plus, in-town driving means you’re much less likely to be far away from a charger, so the stakes are much lower.

An overall number is less important for city driving, so I think a better way would be to consider this part in terms of the average American commute (this can be adapted for whatever country wants to use it, of course) which is, according to the most recent Census Bureau data (2019) 27.6 minutes of travel time.

Ideally, we’d like that in miles, not minutes, and for that I had to go back to 2003, a time of 26.4 minutes and an average of 15 miles each way. So, let’s up that number a bit to be closer to the 1.2 more minutes of the 2019 commute, and settle on, oh, 17 miles each way, for a total of 34 miles. Hell, let’s make it 35, just to be safe.

So, city ratings for an EV should be considered in terms of how many days of commuting could you do between charging? That would mean that a hypothetical EV that gets 250 miles of range on city-cycle testing would get a city rating of about 7 days.

That would give some approachable, real-world perspective about what a driver could expect. For that car, they could, if pushed, go a week between charges for an average 35-mile daily commute.

Now, I also think to actually get the raw range number for this, we should eliminate dynamometer tests and make the EPA get out of their cozy offices and do real-world tests.

These city-cycle real-world tests should include start-and-stop traffic, at least one instance of hard, near-panic braking, at least one very hard, race-for-pinks-at-a-stoplight takeoff, and speeds that range from 5 to 45 mph.

And, the test should be done at least three times: once in cold weather, once in hot, once in something in between. The average of the three runs gives the number that the days-between-charge rating.

For highway range, the raw number is what matters. And to test it properly, the highway test must also be a real-world test, with the car prepared as it would be for a road trip: full number of passengers and their luggage to give the worst-case scenario (barring anything strapped to the roof or a trailer).

The test needs to include highway routes that allow for as much driving at a steady 75 mph as possible. Maybe factor in a pee break or two because I’m not a monster and that’s realistic for a road trip, anyway. People gotta pee, and you gotta buy your Combos somewhere.

The car will start with a nearly-full charge (normally, EV batteries do best when just charged to 80 percent or so, but for road trips, 90 percent can be used) and be driven at 75 mph as long as possible until the battery is depleted.

Like the city test, the highway test should be conducted three times, in hot, cold, and mid-range weather, with the results averaged. The resulting range number will be given in miles as well as how many hours were driven from start to completion.

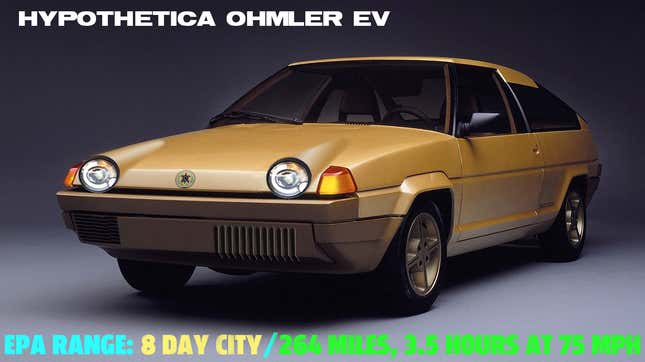

So, with that in mind, a hypothetical new EV range number would look something like this:

Our sample car here, a 2022 Hypothetica Ohmler EV, was tested on the new EPA range cycle and found that with a 35 mile/day commute, the Ohmler could go just over eight days before depleting the battery.

On the highway, starting from a 90 percent charge and driving as long as possible at 75 mph, the car went 264 miles for a total of 3.5 hours at 75 mph.

That’s not bad! You should consider an Ohmler for your next EV!

I don’t think I’m the first to suggest this sort of idea by far, but I think it makes sense. EV ranges need to accept the fundamental differences in city and long-trip driving, and one range number does not cover that well enough.

A city range in terms of average daily drive mileage and a highway-speed trip length/time estimate make a lot more sense, and would help consumers understand better what their new EVs can be reasonably expected to do.

I’m sure demanding the EPA test in the real world instead of on dynamometers will be met with complaints about cost and time, but come on EPA employees, it’ll be fun to get out of the lab! It’ll be worth it!