Jalopnik’s first-ever budget EV build is here, and it’s going to be incredibly challenging. With the help of automotive engineers in the Detroit area, I’m doing an electric vehicle conversion on this rusted-out 1958 Jeep Forward Control that I bought sight unseen for $1500. If your first reaction is “My god that thing looks rough!” trust me when I say: That’s the least of my worries.

First there was Project Swiss Cheese, a $600 Jeep Cherokee with no floors. Then there was Project Slow Devil, a dilapidated 1948 Willys farm Jeep. Then Project Redwood, an $800 1986 Jeep Grand Wagoneer that I had to dig out of a backyard in western Michigan. Then came the legendary $500 Project POStal, my rotted-out 1976 Jeep DJ-5D Dispatcher (RIP) that even I suspected might have been too far gone.

I brought these vehicles back from the dead, and took them on awesome road trips to Moab, Utah, from southeast Michigan. There was also the Holy Grail Jeep Grand Cherokee, a $700 rare manual transmission Jeep ZJ that my friend and I fixed and drove 1,700 miles from the high plains of Colorado back to Michigan. And there was Project Krassler, my $600 Diesel Manual Chrysler minivan that I fixed and road tripped thousands of miles through Europe (and will continue to road trip in the future).

These projects have occupied some of the most important years of my life, requiring hundreds of hours of wrenching and thousands of dollars of my own money. As my 20s come to a close, I look back at these adventures with mixed feelings. On one hand, I reached tens of millions of people, got to lead awesome teams of friends to solve technical problems and partook in some life-changing road trips, meeting fascinating people along the way. On the other hand, untamed passion led me to spend much of my 20s working the longest work-weeks for years without even realizing it, and that’s created some gaps elsewhere in my life.

This could all just be normal philosophizing for a man about to turn 30, but in any case, I’m ignoring these thoughts to do it all at least one more time. And this project will be the most challenging yet. By far. Because I’m going electric.

The Willys FC-170 That I Will Convert Into An EV

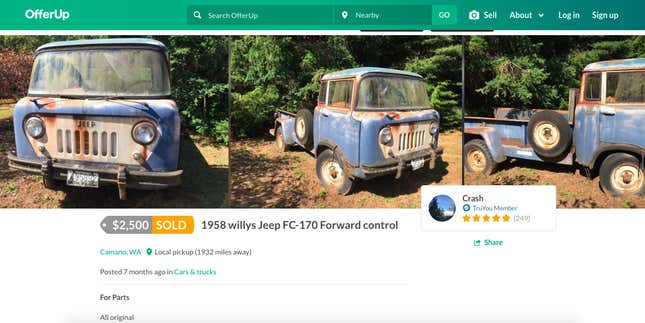

“Forward Control in Camano, WA” read the July 28, 2020 email’s subject line. “I know [you’re] trying to get rid of cars, but this is one any Jeep enthusiast can appreciate,” the sender, Tom, wrote in the body, concluding with a link to the online marketplace OfferUp. Upon clicking the hyperlink, my heart melted.

“Oh my, it is the pug of automobiles!” I thought to myself, my pupils having been replaced by big pink, throbbing hearts.

After a few exchanges with Tom, he told me he has five acres with “plenty of room to stash [the Jeep].” From there, things got a bit weird, with me telling the seller over the phone that I was interested, the seller showing up to Tom’s house with a trailer willing to sell me the Jeep for only $1,200, Tom telling me not to buy this Jeep for various reasons that I’ll let him expound upon (he’s writing a detailed article on this vehicle’s condition — expect that late this week or early next), me backing out, and then me ultimately following my destiny and succumbing to the Jeep’s cuteness (but paying $1,500).

Tom sent me a number of images of the vehicle while I was deciding whether to buy it, including this rather shocking one of the interior:

Back in September, I showed this photo to Sandy Munro, manufacturing engineering expert at benchmarking company Munro & Associates, and he absolutely lost it:

Here a video that Tom took of the seller discussing the FC’s underbody:

If I’m listening to this video correctly, the seller is describing the condition of the vehicle’s frame, saying the passenger’s side is solid. As for the driver’s side? “I mean...the column ain’t gonna fall through.”

Oh boy.

The vehicle has sat on Tom’s property for over six months now. Tom, a long-time wrencher excited about the project (and also a saint for storing this car so long), has been impatiently asking me if he can wrench on the Jeep. He recently dumped some automatic transmission into the vehicle’s flathead inline-six “Super Hurricane” engine, and turned the motor over by hand (he forgot to put rags in front of the spark plug holes—see mess above). It’s not seized! Even though I’ll replace the engine with an electric motor, this is great news. I’ll explain why later.

Until then, here are some other photos Tom took of my new off-road project:

And here are some more recent photos of the FC in snow:

How can a vehicle look that cute? I just don’t understand.

The Jeep’s overall condition is still not clear to me. Tom will be writing a post soon including more detailed photos and descriptions. I’m a little scared; the Jeep can’t be that bad, right?

An Engineering Project, Not Just A Wrenching Project

This EV project has potential to to be unlike anything you’ve seen before on a mainstream media site. The FC will be different than my previous crap-cans in that it’s going to be a true engineering endeavor, and it’s going to bring readers real insight into how automotive engineers do their jobs.

My past undertakings involved fixing mechanical and electric problems on some of the most worn-out vehicles I’d ever seen. While my friends and I did often have to come up with ingenious solutions to these problems, aside from maybe a few instances like when I had to design a safe frame repair, I wasn’t really engineering. I was repairing and assembling. Things are going to be different with this FC.

Over a year ago, I assembled a team of electric vehicle engineers, and started a monthly meeting at a bar in Royal Oak, near Detroit. We discussed electric cars broadly — the challenges the technology faces and where we see it going in the coming years. But the main focus of our meetings was to build out a plan for an electric vehicle build at Jalopnik. We talked about automobiles to use as platforms, and how to convert those vehicles to EVs in a way that made sense, and — critically — on a budget. That last part is tricky, because EV components are relatively expensive.

COVID-19 and resulting stresses brought those meetings to an end, but not before I had some idea of how I wanted to proceed. It was clear I needed a body-on-frame vehicle that would allow me to easily customize the chassis to accept batteries. If I could find a machine that had the space to accept an entire battery pack, then I could use the cooling system integrated into that pack instead of having to build something custom for individual modules. I ultimately chose the Willys FC-170.

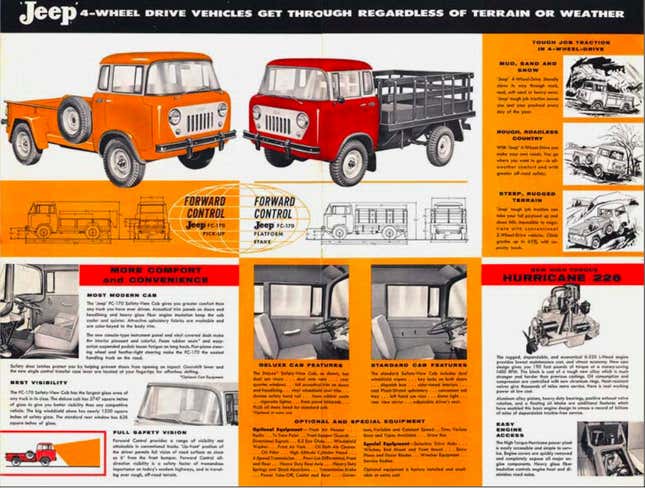

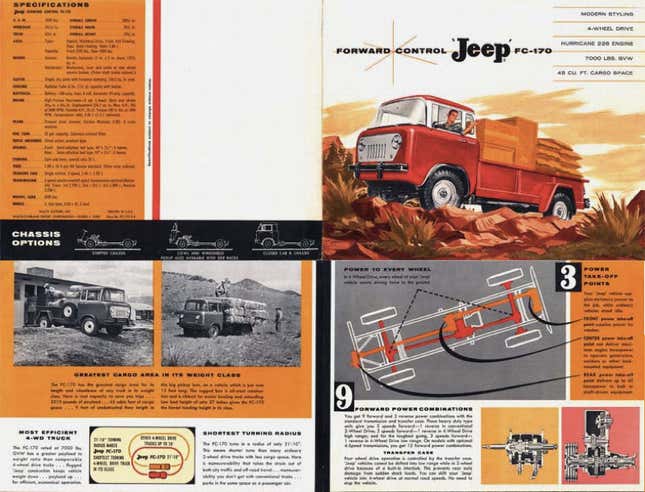

The FC-170 is similar to early CJ Jeeps in that it used a three-speed “T90" manual transmission, Dana 18 transfer case, body-on-frame construction, leaf spring suspension all the way around, and ridiculously short gearing in the solid axles axles.

It was also a utility vehicle, meant for hard duty on the farm and in a factory setting. Unlike CJs, though, the FC was specifically designed to maximize payload while keeping the overall vehicle length to a minimum thanks to a Forward Control design that put the driver’s feet ahead of the front axle (the engine sits between the driver and passenger). It’s an incredible machine, and it should offer plenty of space and modification potential to allow for an EV conversion.

There’s so much more to discuss about this project in addition to what condition the Jeep is in. How will I even get the Jeep from Seattle to Detroit?Which components will I use in my EV conversion? How will I get all of those components to work together in a system? How will I set up the four-wheel drive system? How long will this take? More on that and the seemingly endless list of other challenges soon.

For now, I’ll just reiterate that this project’s goal is to not only provide insight into how electric cars work, but also to show readers how the automotive engineering process works.

Obviously, I’m not building a car from scratch, but I am installing an entirely new powertrain into an old chassis. To do this properly will require CAD modeling, powertrain calibration, cooling system design and integration, electrical system design and integration, and on and on. I aim to build a team of volunteer enginerds, to meet regularly in “Chunk Teams” (This is how many automakers break up vehicle programs — into groups such as body, chassis, electrical, interior, etc.) over Zoom, with locals eventually joining me in the shop to actually spin some wrenches.

This is going to be automotive engineering for the world to see, and it’s going to be epic. If you are an engineer in the auto industry (especially an EV engineer), and you want to contribute your skills to this project, email me at david.tracy@jalopnik.com. You will receive payment of zero dollars, to be dispersed biweekly, with a holiday bonus of f%&k all. Surprisingly, 401K matching is offered, though the only amount that we’ll match is the limit as x approaches infinity of e^(-x).

If that’s not compelling enough, just know that, if this overly-ambitious venture works out as I have envisioned, you’ll be interacting with engineers from around the world, all offering your two cents on how this rusty Jeep FC can most optimally be converted into an EV.

Luckily, unlike with my previous projects, we’re actually going to have a budget beyond what I can shake out of my couch cushions thanks to an ad deal with Ford Motor Company, who is Jalopnik’s partner for our new EV/AV initiative, Jalopnik Tech.

Still, I get the feeling that the budget — whose exact details are still being ironed out — is going to be tight given how expensive EV components are. Doing such a build without overspending is my biggest worry.

Expect exciting times ahead.