I don’t generally proclaim myself to be a skilled, or even competent, or even a non-severely untalented businessperson, but I do know that a great way to make money in the car business is to sell more cars. I also know that if you sell cars that don’t need to be replaced for at least three decades, that’s probably not a great business move. Very likely, that’s why Porsche’s research into a long-life vehicle never actually resulted in a production model. Because Porsche likes to sell cars.

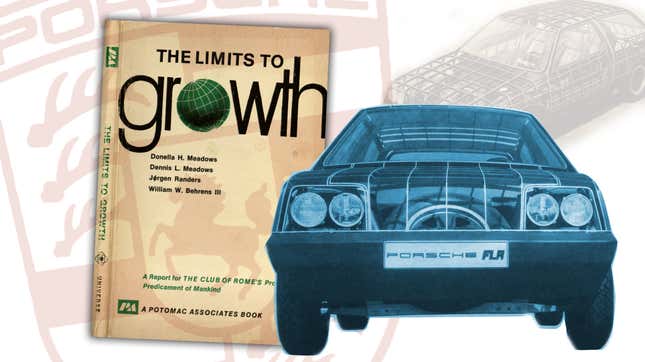

Well, in all honesty, I can’t say for certain that Porsche never brought its 1973 project, the Forschungsprojekt-Langzeit-Auto (mercifully, it’s usually called the FLA), to market because of a fear of driving itself out of business. But it’s easy to imagine that if the FLA had reached production, that could very well have been the result.

It’s not that the FLA was a bad car, because, really, it wouldn’t have been, not at all. But it was a car designed for reasons and goals radically different from those most cars are, and perhaps especially for other Porsches.

The FLA came to be as a result of some very responsible, sober — and frankly pessimistic — thinking. There’s a think tank dedicated to studying basically how fucked humanity is at any given moment, and this club is named the Club of Rome. That’s kind of deceptive, as it sounds like it should be a lot more fun and maybe involve getting drunk and wearing a toga.

In 1972, the club issued a report called The Limits to Growth, based on a series of studies and simulations (some funded by the Volkswagen Foundation) that determined that the unchecked growth of the global economy would lead to severe depletion of resources. By the 21st century, the book proposed, it would be essentially impossible to build cars any more.

The report certainly wasn’t wrong by any means — resources are definitely finite — but the timeline was a bit off, and everything was generally a lot less efficient in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

When the report came out, it was an alarming wake-up call to many, especially in Europe, and Porsche, determined not to go down without a fight, began development of a car designed for extremely long life. That car would require minimal resources and maintenance, so fewer cars would need to be produced because the ones that were built would last so long.

This was a very sober, practical car, not a sports car like Porsche was known for, and as a result had a pretty modest power output: 75 horsepower, coming from a very under-stressed (for longevity, you see — it made that power at a mere 3,500 rpm) inline four-cylinder motor. It used an automatic transmission, mostly because Porsche didn’t trust people enough to drive properly and not wear out clutches and that sort of thing.

Actually, in the context of the era, 75 HP really wasn’t bad at all — plenty of popular cars of the era were making that amount of power or less, and I think Porsche could have gotten away with a lot less. But still, it’s Porsche.

Also very Porsche-like was the positioning of the engine, at the rear but mounted transversely, very unusual for the company.

The engine was said to be overbuilt, and it used a cooling system designed to help the engine reach optimal operating temperature quickly; the oil and air filtration systems were engineered to be very efficient, all for longevity.

Maintenance was designed to be simple as well, with oversize oil reservoirs for the drivetrain to extend fluid change intervals, and piping was made from easily recycled aluminum instead of copper.

Even the electrical system was given a rethink, with silver plug contacts, a contact-free ignition system and a wiring loom divided into removable sections to facilitate repairs without needing to replace the whole thing.

Really, these are all solid ideas, no matter what.

The body design was interesting, too, engineered for practicality and utility more than aesthetics, though I think it’d look pretty cool. It was a hatchback design, vaguely AMC Pacer/Gremlin in shape. But because it had the engine lying flat under the rear floor, it could provide a hatch and a front trunk for some real hardcore practicality.

In this sense, it reminds me a lot of an updated Volkswagen EA266 prototype, the car that almost replaced the Beetle, and one that, significantly, was also developed in large part by Porsche. Though I haven’t found any direct evidence, I wouldn’t be surprised to find that a number of the FLA designers had come from the old EA266 team.

In fact, I think the taillight units used on the FLA were the same as the ones from the EA266, just rotated 180 degrees.

While it was never given a finished body, the skin of the car was to be aluminum (the most easily recycled material in that era before very recyclable plastics) over a frame of corrosion-resistant metal, said to be alloys of iron, chromium and nickel.

The FLA was shown publicly only once, at the 1973 IAA Frankfurt show, and it doesn’t seem to have made all that much of an impact. Humans being what we are, the dire warnings of the Club of Rome report soon stopped being exciting, and we went back to blissfully ignoring the future.

The car is currently in the Porsche Museum, and while it’s easy to dismiss it, the truth is that it was very far ahead of its time. We call these ideas “sustainability” today, and automakers absolutely do care about it—or, at least, their PR departments claim they do.

Cars are designed with recyclability and efficiency in mind today, from the start, and they are leaps and bounds better than what was possible in the early 1970s. The current method seems to be to build cars that can expire and be recycled well as opposed to building cars that last forever, likely because one scenario requires buying more cars and one doesn’t.

Still, as someone who owns multiple cars well over 30 years old, I absolutely see the appeal in a machine like the FLA.