Leading up to the NASCAR Truck Series’ championship race on Friday, where a title would be decided by the highest finisher of four drivers still in contention in that single race, the long shot this season, Matt Crafton, was asked about the potential for him to become the first winless champion in this era of NASCAR.

Crafton, in fact, hasn’t won a Truck Series race since the 2017 dirt-track event at Eldora Speedway, according to the Racing Reference database. On non-dirt race tracks, which currently make up every Truck Series event outside of Eldora, Crafton hasn’t won since May of 2016.

“That would be great, wouldn’t it?” he responded, as quoted by Lee Spencer on Twitter. “I would love it.”

Then came the follow up: Would it bother him at all, knowing he won without actually winning? Nope. Not one bit.

“I would sleep just fine at night sitting next to that trophy,” he said.

Crafton did end up winning the Truck Series title without winning a single race this season, in addition to having the worst stats, by far, of the four drivers who raced for the title. But Crafton probably is sleeping just fine next to that trophy each night, because he played the game in this era of NASCAR—and he won, no matter how absurd it might feel or how difficult it is to fathom.

While NASCAR used to accumulate points over a season and give the title to the driver with the most at the end, the modern era of rules involves a knockout championship format in the sanctioning body’s three top-level national touring series: the Cup Series, Xfinity Series and Truck Series. The numbers of drivers and races included vary by series, but all have short segments of races after which a certain number of drivers are knocked out of the running.

There are eventually four drivers left to compete for the title at the end, and the championship winner is then decided in the final race of the season—all four drivers go in with their points total reset to be equal, and the highest finisher in that single race wins the championship. Nothing else matters, unless a car fails technical inspection after the race and the finishing order needs to be revised.

The process of making it to that final race is thoroughly flawed in the context of racing, which typically and historically gives titles based on consistent success throughout a race season, like NASCAR’s old rules did. There are short intervals between eliminations, meaning some of the highest performers in a season are prone to being knocked out with a couple of bad races or mechanical woes in a row. Here are two examples from the past few years.

Because of that, not everyone who survives until the title race has been one of the top-four performers of the season, but everyone who makes it has an equal chance of winning. Everyone also has an equal chance of a race-ending fluke—like, say, a spec engine failure—undoing an entire season of success.

Basically, if you make it, it’s anyone’s game to win or lose. That’s what NASCAR has wanted for years: to manufacture “game seven” moments at every turn, at the expense of what most of us consider a legitimate championship format. The thing is, not every racing season is a game-seven season, just like not every ball sport makes it to game seven. Sometimes it’s more of a game-four season, and that’s something we all have to live with.

But in the current era of NASCAR, that’s not how things are. There will always be a “game seven,” no matter how competitive it may or may not be.

Thus, when Crafton made it into the Truck Series’ final four this year and had a legitimate chance to become the first champion to not win a single race during their title season since NASCAR introduced the elimination formats—2014 for the Cup Series, 2016 for Xfinity and Trucks—it was an odd scenario for everyone.

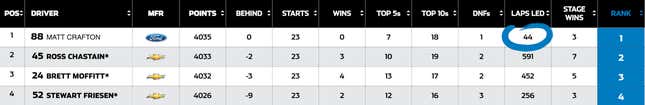

But that’s exactly what he did: He won the 2019 title, having finished second in the final race at Homestead-Miami Speedway and without having won a single race this year. His stats on the final leaderboard look like they belong in an entirely different category from the rest of the final four, with his zero wins ahead of the drivers he beat out, who had three, four and two wins, respectively.

He also had fewer top-five finishes than any of the other drivers he raced for the title against at the end of the 23-race season, with his seven listed ahead of Ross Chastain’s 10, Brett Moffit’s 13, and Stewart Friesen’s 12. (They finished in that order in the points, based on where they finished in Miami.) In the laps-led category for the season, Chastain has 591, Moffitt 452, Friesen 256, and Crafton just 44. Nine of Crafton’s laps led came at Homestead.

It’s almost hard to look at that finishing order given how middle- and bottom-heavy it is in terms of success this year, but that’s just a side effect of NASCAR’s insatiable need to make the championship battle as entertaining as possible—no matter what kind of story the numbers tell at the end.

But Crafton, and the rest of the drivers, all knew that going in. That’s just how things are now, and how they’ll likely stay for a long time—perhaps for good. They all played the game, but this time, in a “Final Jeopardy”-style there’s-no-way-he-actually-did-that move, Crafton won.

And in modern NASCAR, that’s fair game.