On February 28, 25-year-old bike messenger Aurilla Lawrence was killed by a truck driver in Brooklyn. After killing her, the truck driver did not stop. Following a familiar pattern whenever a cyclist is killed by a driver, the NYPD rushed to make excuses for the driver, hypothesizing the driver didn’t stop because they didn’t realize they had hit someone. According to a lawyer who viewed footage of the nighttime crash, as reported by Streetsblog, the truck approached Lawrence from behind and accelerated past her.

Lawrence was one of 19 cyclists to die in New York City so far this year, almost doubling the total for all of 2018. Earlier this month, the Brooklyn district attorney’s office announced it would not be charging the driver because the evidence suggests Lawrence hit a pothole which caused her to fall onto the street and then be run over, unbeknown to the driver.

Four days before the DA announced they would not be pressing charges, another cyclist died in the city, this time without any ambiguity about fault or blame. In this case, the death of 52-year-old Jose Alzorriz of Park Slope was caught on tape in broad daylight.

While he waited at an intersection in southern Brooklyn, a driver sped through a red light and T-boned an SUV, which flew into Alzorriz and pinned him against a building. The whole thing was caught on a dashcam. As of this writing, the driver of the speeding car that ran a red light, killing Alzorriz and injuring two others, has not been charged.

While there are many differences between the deaths of Lawrence and Alzorriz—one at night shrouded in mystery, the other due to obvious recklessness caught on camera in broad daylight—there is one unifying trait: both occurred in areas where the city’s signature safe streets policy has utterly failed.

Vision Zero, launched in 2014, is Mayor Bill de Blasio’s commitment to reduce traffic fatalities to zero within a decade; a ten-year pledge for an elected official term-limited to eight years of service. And now, halfway through that ten-year timeline, there is scant evidence it has saved many lives at all.

In Lawrence’s case, her death occurred in a neighborhood where cycling and pedestrian injuries have actually increased during the Vision Zero era. As for Alzorriz, he was the second cyclist killed on Coney Island Avenue this year. There have been 578 crashes on that stretch of road in the last year, or an average of one and a half per day (elected officials have urged the Department of Transportation to expedite a safety study of that corridor).

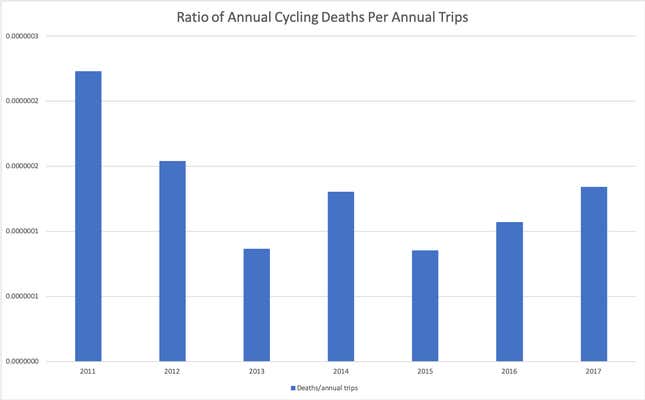

The numbers don’t look any better citywide. In the three years before Vision Zero launched, there was an average of 17.3 cycling fatalities per year, according to the city’s Vision Zero dashboard. In the five and a half years since, the average number of cycling deaths per year is 17.5 (I’m counting 2019 as a full year, even though, obviously, 2019 isn’t over yet). The stats look slightly better when accounting for increased ridership, but even then there is no clear sign of progress in the Vision Zero era, especially when projecting for 2019.

Vision Zero is failing to have a meaningful impact because it targets the wrong goal. The logical flaw here, at least as implemented in New York City, is quite basic: it is a policy that requires dead cyclists as a prerequisite to safety improvements. Time after time, DOT ignores calls for safety improvements on dangerous streets for years, only to expedite projects once someone inevitably dies.

In this way, Vision Zero in NYC puts the cart before the horse when it comes to safety and ridership. Yes, safety is a worthwhile goal, and nobody wants to see more dead cyclists (well, most people don’t). But there are several proven ways to make streets safer for everyone—lest we forget the 62 dead pedestrians so far this year, too—that don’t involve playing whack-a-mole with dangerous intersections. Unfortunately, DOT is doing none of them.

First, the academic literature is quite clear that, when it comes to cycling, there’s safety in numbers. The more cyclists riding together, the safer they will be. Cyclists intuitively know this, which is why cycling communities around the world organize “Critical Mass” rides. It is also why many cycling-heavy cities around the world focus on bike freeways or bike highways to move a lot of people quickly along safe, protected corridors entirely separated from vehicle traffic.

Rather than adopt these internationally-accepted practices, New York City has opted to draw a lot of lines of paint on the road, designate them bike lanes, and then brag about the dozens of miles of bike lanes it builds every year.

Not only do most of these miles—nearly all of them outside of Manhattan—offer no real separation from traffic, they constantly force cars and cyclists to compete for the same road space at intersections and as cars enter and leave parking spaces.

On top of that, this paint and pray strategy undermines the concept of critical mass. Instead of directing cyclists to a few carefully designed, safe, protected routes, it spreads them out among dozens of lazy, dangerous, and haphazard “bike lanes” inviting conflict.

Nearly every cycling fatality this year has happened in an area with no or poor bike infrastructure. In this way, both Lawrence and Alzorriz’s deaths are illustrative.

In Lawrence’s case, the area around Broadway and Myrtle in Williamsburg-Bushwick is a veritable protected bike lane desert. In 2016, I was doored—when someone in a car opens a door into the path of an oncoming cyclist—while biking along an unprotected bike lane in that neighborhood (I was, to my everlasting shock, unharmed and did not file a police report). The lone exception is Grand Street, which has a “protected” lane in one direction with plastic poles ostensibly providing that protection, but they’re placed so far apart that even large trucks can drive between them to park in the bike lane.

As for Alzorriz, he was only a few blocks over from the Ocean Parkway Greenway, a 125-year-old greenway that rides like it hasn’t been maintained since the day it opened (although a $1 million fix is apparently underway). Yet, it remains the only north-south protected bike lane in all of southern Brooklyn.

It is, also, not protected despite DOT claiming it is. Along the entire path, drivers have a green light to make turns across the cycling path at the same time as cyclists have a green light to cross the intersection. In this sense, the greenway almost makes things more dangerous, because drivers zooming along Ocean Parkway rarely take the time to check the path for oncoming cyclists who are often in their blind spots, assuming that because they have the green, they have the right of way.

So, it’s no surprise riders like Alzorriz and Lawrence ride on streets without any biking infrastructure at all. What’s the point of going out of your way when even the bike lanes are unsafe?

As if in response to this lack of improving safety, bicycle ridership in the city appears to have plateaued after decades of explosive growth. Since 1990, the number of estimated cycling trips per day almost quintupled from 100,000 per day to 490,000 in 2017, according to the Department of Transportation.

But much of that gain came prior to Vision Zero. The sharpest growth occurred between 2011 and 2014; daily cycling trips increased 55 percent in those three years.

Since Vision Zero launched in 2014, the growth has slowed. An estimated 420,000 cycling trips took place per day that year, compared to the 490,000 in 2017, or just 16 percent more over those three years, even though the city’s bikeshare service launched mere months before the Vision Zero era kicked off.

DOT hasn’t released citywide cycling figures since 2017, but East River bridge crossings—the only way to cycle between Brooklyn/Queens and Manhattan—peaked in 2016. By 2018, East River crossings by bike dropped seven percent from the 2016 high, reversing all the gains in ridership since Vision Zero began.

When it comes to cycling, ridership and safety are closely intertwined. Most people won’t bike if they don’t feel safe, but the more people who bike, the safer bikers are.

The close relationship between the two can lead to a false impression that a policy focused on safety will increase ridership, but in fact it’s the other way around. By explicitly targeting ridership as the key metric, it forces policymakers to constantly ask: what makes people ride, and what makes people stop riding?

Safety will, of course, be a key part of that calculus. Over the last year, at least a dozen New Yorkers have told me that they no longer ride bikes as a form of transportation because they don’t feel safe.

But safety isn’t the only factor. So are things like convenient, secure bike parking, timing traffic lights for cycling speeds for quicker and easier journeys, good road conditions, and sensible laws that acknowledge bicycles are not cars and should follow different rules.

But by targeting safety, and only safety, Vision Zero has nothing to say about those important factors that dis-incentivize people from riding bikes more regularly.

And by targeting deaths, and only deaths, Vision Zero has nothing to say about all the near misses, close calls, and stressful interactions with multi-ton vehicles looming mere inches away from them, which is all according to plan as far as DOT is concerned. One doesn’t have to die on their way to work to find the heat and exhaust emanating from a cement truck blowing directly in their face less than pleasant.

And we should want more people cycling in our cities. Not just for safety reasons—far more people show up to a de Blasio presidential campaign event than have been killed by New York City cyclists over the last decade—but for environmental, health, and other public policy goals.

Utrecht, one of the most bike-friendly cities in the world, has invested an average of $55 million annually towards bicycle projects and infrastructure, including massive parking garages just for bikes. That is roughly five times the annual outlay of de Blasio’s reactionary five-year “Green Wave” initiative in response to all these dead cyclists, even though New York City’s population is roughly 25 times that of Utrecht’s.

But Utrecht and other cities like it aren’t splurging. In fact, the Netherlands as a whole, and cities like Utrecht individually, have found investments in cycling infrastructure pay for themselves by reducing expenses elsewhere in areas such as health benefits and transportation costs.

“Cycling is like a piece of magic,” a Utrecht city official told the New York Times in 2017. “It only has advantages.”

It is worth remembering that the global model for an ideal cycling city has a very different vision than New York does:

How can we encourage even more people in and around Utrecht to use their bicycles? By organising specific activities and by taking measures included in the ‘Utrecht - we all cycle!’ Action Plan. ‘Utrecht -we all cycle!’ is Utrecht’s response to the challenge of becoming a world-class bicycle city.

....

It is our ambition to create an essentially different city: a city that is healthy, sustainable, accessible, liveable and attractive. A city that is performing well in terms of quality of living, with clean air and less traffic noise, which contributes to a favourable climate for new inhabitants and businesses. Making Utrecht the ideal bike-friendly city requires innovations. With the construction of the largest bicycle building in the world well underway and boasting the first Parking route for bicycles, Utrecht is creating more space for bicycles and a better bicycle and cycling experience.

Cycling represents freedom; freedom for everybody to move through the city in a way that is convenient, pleasant and cheap. ‘Best cycling city in the world’ means that people of all ages be able to cycle safe and that even more people opt for using the bicycle, also between Utrecht and its neighbouring municipalities.

The word “safe” or “safety” appears only once in their vision, and even then only towards the bottom, in the context of “people of all ages” feeling safe to ride. In other words, Utrecht’s vision is “We All Cycle.” New York’s is We Don’t Die.

Theirs is a positive vision, based on what they want their city to be, not what they fear the most. It is about unleashing the joy of riding a bike to make a better place to live, not fighting the fear that riding a bike may entail. It is not a vision of zero, but an idea for all. In order for American cities to harness even a fraction of that, it will require demanding more of our cities than mere survival.