The 2020 Corvette C8 is here, and by now you’ve probably seen exterior and interior photos, and read about all the performance figures. That’s great, but what you really want is to learn about the hardware, so here’s what I got from an interview with a Corvette engineer and through sifting through GM’s technical literature.

The Corvette is getting lots of love for its design, cool features, and reasonable starting price tag, and though I obviously haven’t driven the car yet, it’s probably safe to say that the stylists, product planners, and finance folks really don’t deserve nearly as much credit as the engineers do. So let’s focus on some engineering attributes of the new Corvette, shall we?

The Body Structure

The new Corvette’s main body structure is made of aluminum, and, according to the car’s executive chief engineer Tadge Juechter, “makes the most use of high pressure die-casting in General Motors history.”

Juechter describes the six largest castings that make up the main structure—castings that GM names the “Bedford Six” after the location where they’re built: Bedford, Indiana—as “enormous.” Those castings are highlighted below in blue and also shown in orange two images above:

Those big castings, Juechter said during the reveal, were designed to minimize the number of joints in the body, reduce mass, and increase stiffness. “They are the key to making this the stiffest Corvette in history, which in turns contributes to great driving dynamics,” he said. According to Chevy, the new body is 10 percent stiffer than that of the outgoing C7.

Another thing Juechter mentioned was the center tunnel, which acts as the car’s backbone. Chevy has been using such a design on the Corvette since 1997, Juechter said, and its main job is to keep the car nice and stiff to allow for better ride and handling (since a stiff structure means the precisely-tuned suspension, and not the body, can do all the flexing). The backbone, the chief engineer said, has been completely redesigned on the C8, and the setup allows the vehicle to have low rocker panels.

Chevrolet expounds on this last bit in its press release, saying the low rockers allow for easy ingress and egress. “Unlike some competitors,” Chevy says, “there’s no need for oversized rocker panels to bear structural and load weights, making it easier to enter and exit the vehicle.”

The backbone design, Chevy says, was also key to helping enable the car’s transparent or carbon fiber removable roof panel (presumably because it would otherwise have to bear load), to allowing for a right-hand drive variant, and to yielding good interior and front trunk space.

Speaking of the front trunk, Juechter said the tubs for the two storage areas—as well as the dash panel—are made of a special, extra-light moulded fiberglass made with a “proprietary resin.” The photo above shows those frunk and trunk tubs.

While we’re on the topic of fibers, check out this extremely unimpressive-looking curved carbon fiber rear bumper beam. It’s apparently an industry first:

Anyway, that’s about all I know about the 3,366 pound (not including fluids) Corvette’s body so far, but what you came here to see is hardware, and I’m thrilled to say that my colleagues Andrew Collins and Tahsin Hyder got some great footage of the structure:

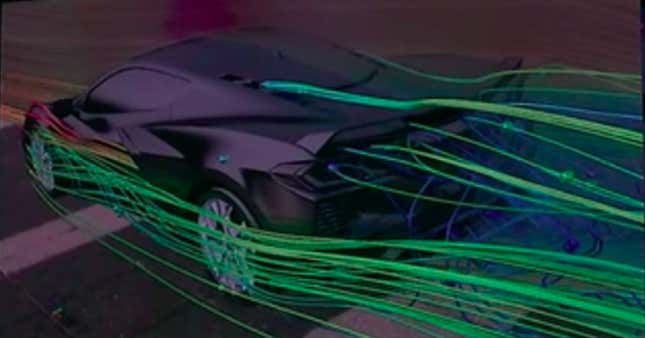

Aerodynamics and Powertrain Cooling

I had a chance to speak with Rich Quinn, Cooling System and Thermal Lead Development Engineer, about how the Corvette’s cooling system works, and it’s quite interesting.

Up front are two large outboard radiators, which send cold liquid coolant in parallel rearward to cool the engine and transmission.

There’s no dedicated air-to-water transmission cooler. Instead, as the two radiators send cold coolant rearward toward the engine bay, the fluid tees off to cool three main components: the engine itself, the transmission’s oil-to-coolant stack heat exchanger (which is mounted to the trans and shown in a photo later in this story), and the engine’s stack oil-to-liquid heat exchanger (which is mounted to the motor).

In the Z51 package, Quinn told me, there’s a dedicated heat exchanger behind the passenger’s side large side vent. Here’s a look at it:

“There’s a separate dedicate coolant loop on the Z51 that runs through the third radiator in the rear so that third radiator has a dedicated airflow path, a dedicated cooling fan.” he told me. “That adds bulk cooling, but it also cools the coolant that’s running into the trans oil liquid-to-liquid heat exchanger.”

In other words, this heat exchanger further cools the liquid coming from the radiators up front, and then sends that extra cold water to the transmission. “It’s just like an addition to the front two radiators in terms of its total capacity. Since it’s cooler coolant coming out of that [rear heat exchanger], we use that, run it directly to the trans cooler stack heat exchanger,” Quinn said over the phone.

“It’s a really effective way of getting good capacity and also not overcooling in cold weather,” he told me about the design, which—like many old-school “in-tank coolers,” uses the engine’s radiator outlet coolant to keep the transmission cool.

Even though the Z51 package adds a heat exchanger behind the passenger’s side vent, the main purpose of those aggressive holes on the side of the vehicle is not to feed heat exchangers to keep the engine cool. “The two rear inlets, their primary function is essentially taking exhaust thermal energy out of the rear compartment,” he told me.

The main point, there, is to provide relief to components near the exhaust such as rubber engine mounts and suspension components, which degrade quickly when subjected to high temperatures.

Air enters those side vents, absorbs exhaust heat, and is ducted away through a number of outlets, including the big vents in the rear bumper shown below.

“When you’re going down the road, [air] usually translates across the exhaust manifold, over the muffler in the rear, and it exits over the visible vents you see in the rear,” he told me, saying that, though there are a number of exit paths, the primary one for the air that has flowed through the engine compartment is actually the metal mesh behind the muffler. Here’s a look at that:

But there are more outlets than just those on the very rear of the car. On either side of the rear glass, you’ll notice some fairly large vents. Those, Quinn explained, are there to help remove heat from the engine bay when the car is at idle via natural convection (hot air will rise straight up through those vents):

There are, of course, a number of other aerodynamic attributes that are probably worth mentioning, like this “hybrid rear spoiler” which is taller on the outsides, and “touched down” in the center.

I’m looking forward to learning more about this vehicle’s aero properties.

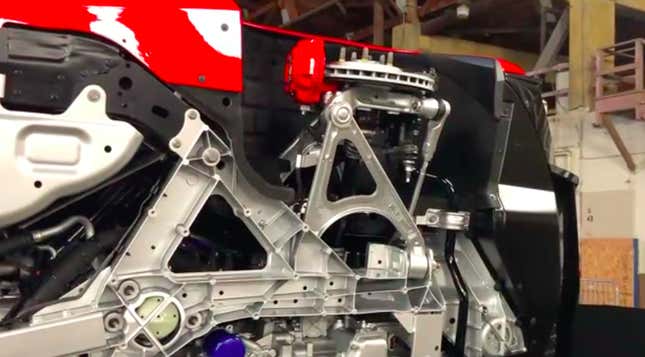

Steering and Suspension

The biggest news about the new Corvette is, of course, the fact that it’s mid-engine, and according to Chevy, one of the benefits of this setup is the shorter nose, which means a shorter, straighter, and stiffer steering system (which I’m assuming refers mostly to the intermediate shaft). Juechter says the steering system (which, in case you’re curious, offers a 15.7:1 ratio) is now 50 percent stiffer than before, going on to say: “That makes the driver’s input to the chassis nearly instantaneous.”

Another benefit of the mid-engine setup, he says, is that the driver’s center of gravity is right above the car’s. “The car literally rotates around you in a turn,” he says.

He also mentions that the mid-engine setup—and particularly the rear weight bias that it creates—improves straight-line acceleration, and helps improve the steering experience since it reduces the need for steering assist. In addition, Chevy mentions visibility and utility (the car has two trunks) as benefits of the architecture.

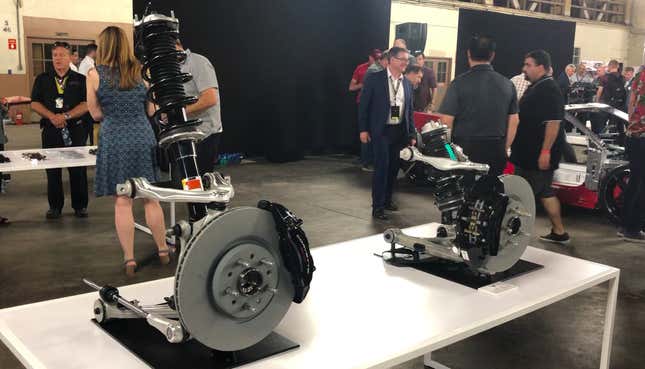

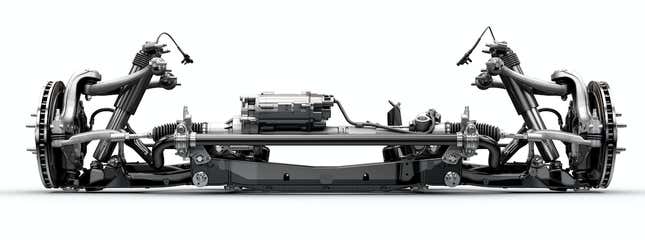

Now it’s time to look at the suspension, which is markedly revised from the outgoing car’s (shown below), with the biggest news being the deletion of the transverse-mounted composite leaf springs at each axle. If you look closely at the image, you’ll be able to see the C7’s black composite leaf springs that span from lower control arm to lower control arm on each axle:

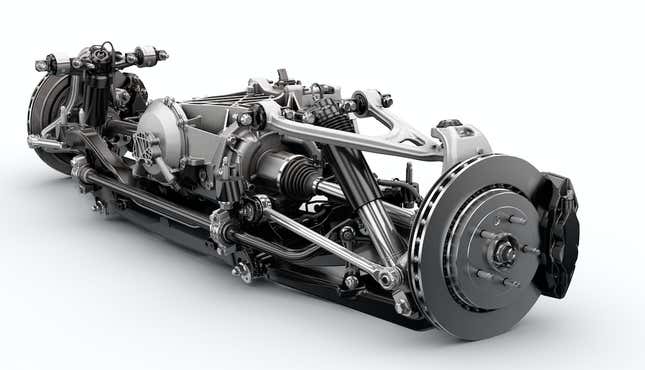

The C8’s design is quite different. Here’s a close-up shot of it:

You’ll notice the coilovers in the front and rear. The general design is similar to that of the outgoing car, as both used a short/long arm double-wishbone setup with monotube shocks and available Magnetic Selective Ride Control, which you can learn about below:

The C8, though, has a forged aluminum upper control arm in the front and rear, while the C7 used cast upper and lower control arms.

Above you can see the basic suspension setup for the new C8, and here’s how the front and rear suspension cradles looked on the outgoing car (the most obvious difference, again, is the lack of coil springs):

Autoweek provides some possible reasoning for the move away from leafs, writing:

The Corvette’s familiar CRP leaf springs are effective devices for a lot of reasons, but they’re actually more cost-intensive than coil springs, and with the midengine layout the packaging space for transverse leafs has nearly disappeared.

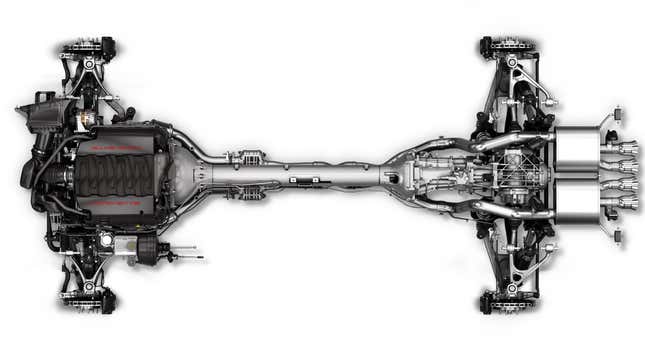

The Engine

The second term in the “mid-engine” phrase that has everyone so excited refers to a 6.2-liter Small Block V8 that Chevy calls the “LT2.” It makes 490 horsepower and 465 lb-ft of torque in standard form, and the performance exhaust that comes with the Z51 package brings those figures up to 495 horsepower and 470 lb-ft.

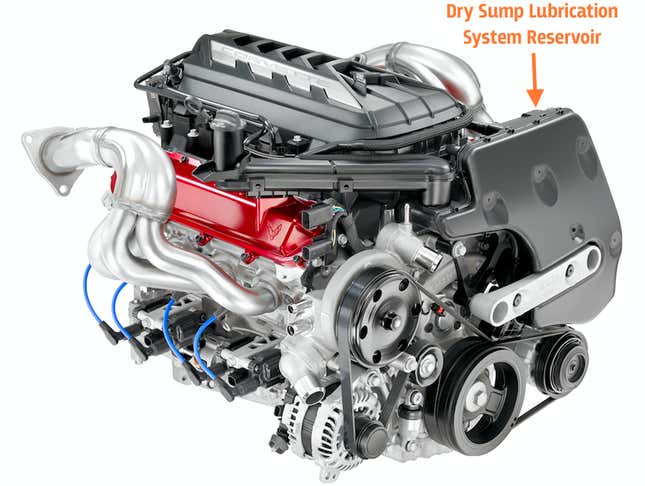

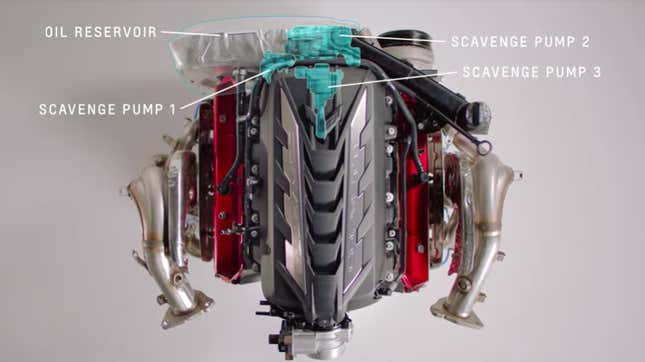

The biggest change to the motor compared with the outgoing one deals with the lubrication system. “For the first time ever,” Chevy says in its release, “the base Stingray will use an engine-mounted dry sump oil system and three scavenge pumps for improved track performance.”

The new setup, which includes a reservoir (pointed out in the image at the top of this section) mounted to the front of the engine, allows for a lower center of gravity. “A low profile oil pan reduces mass and lets us mount the whole engine lower in the chassis than we’ve ever done before,” Juechter said in his remarks during the reveal. Indeed, Chevy mentions in the press release that, where it mates with the transaxle, the crankshaft’s centerline actually sits an inch lower to the ground. This, in theory, can yield better handling.

Chevy also says in the video that the dry sump setup in advantageous when the vehicle experiences high lateral accelerations, as it prevents oil starvation issues from sloshing or from frothing due to windage. From Chevy’s press release:

During serious track driving, oil volume remains high to avoid diminished performance. The new Stingray’s lateral capability is greatly improved, so the LT2’s dry sump lubrication system had to be redesigned to provide exceptional engine performance even at lateral acceleration levels exceeding 1G in all directions.

Other changes to the motor include a higher oil cooler capacity, and a number of alterations in the aesthetics, since the motor is now visible through the rear glass. Check out the red valve covers and what appears to be a rather aggressively designed, gray airbox:

And here are some graphical depictions of that motor sitting in the vehicle:

Eight-Speed Dual-Clutch Transmission

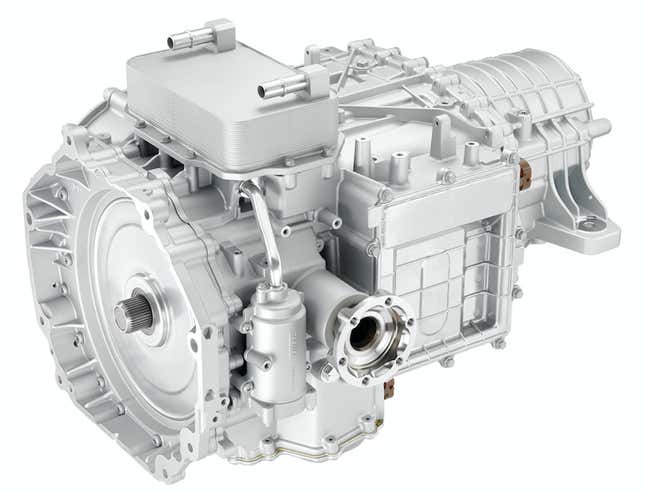

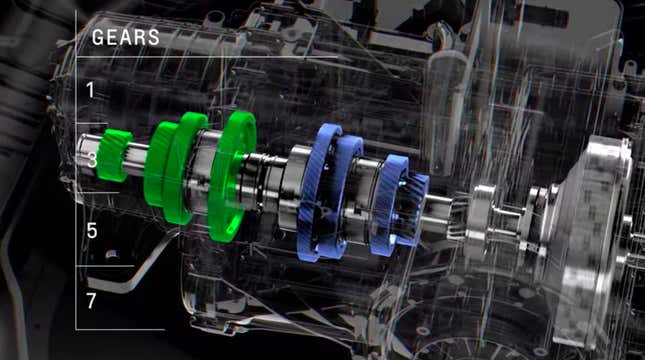

The new Corvette’s 6.2-liter V8 is bolted to a new Tremec eight-speed dual-clutch transmission that Chevy says has a low first gear to yield better launch times, and closely spaced second-through-sixth gears to keep the engine near its peak power operating point on the track. Gears seven and eight, Chevy says, are tall to keep engine speed down to yield fuel economy and lower engine stresses during highway cruising.

The video above shows the dual-clutch setup, with its two clutches—one that actuates even gears, and one that actuates odd ones—arranged on a concentric shaft. Chevy says the new Corvette can snap off shifts in under 0.1 seconds, and can keep 100 percent of torque from the engine applied through the driveline even during the shift.

“During very aggressive launches, we can actually drive torque through both shaft clutches simultaneously.” Ed Piatek, the Corvette’s Chief Engineer says in the video above. “So you’ll be on an upshift engaging third gear but still driving torque through second as you’re engaging third.”

Chevrolet says its goal for this transmission was to provide the “driving engagement of a manual with the speed and smoothness of an automatic.” That seems like a tall order, since there’s no clutch pedal, but there are paddle shifters, and there is a “double paddle de-clutch feature,” which Chevy says “allows the driver to disconnect the clutch by holding both paddles for more manual control.”

I reached out to a Chevy representative to learn more, and found that this just seems like a way to listen to that sweet, sweet V8 sing. “[It is] exactly what it sounds like,” he told me. “Pull both [paddles] and it disengages to simulate neutral. Good for some fun revs.”

Shifting that transmission into Drive, Reverse, Park, and Neutral involves using an “Electronic Transmission Range Selector,” whose P and N switches are buttons and whose D and R buttons are actually pull toggles. They seem pretty interesting; here’s a look:

That transmission, along with the 495 horsepower V8, should yield a 0-60 mph time in under three seconds, Chevy claims. That is, when equipped with the Z51 Performance Package we mentioned earlier. The kit adds larger brake rotors, performance tires, a special front splitter and rear spoiler, brake cooling inlets in the front, a performance exhaust, more cooling capacity, and an electronic limited slip differential with a unique gear ratio.

That’s all the technical nerdiness I have for the new ’Vette, but I’ll keep writing more as I get it, as this is clearly a fascinating machine.

Update July 19, 2019 11:10 P.M. : This article has been updated with an additional awesome photo of the inside of the transmission. I also added the vehicle’s dry weight.