It’s easy to assume the worst when you hear that NASCAR is getting sued for racial discrimination, given the organization’s Deep South roots and its persistent lack of diversity. But when Terrance Cox III made big headlines by filing a $500 million discrimination lawsuit, it was the latest salvo in a more personal war—a running antagonism between one man and NASCAR, involving a string of protests and discontinued self-organized philanthropies.

Cox, who is black, is the CEO of Diversity Motorsports Racing, an organization that wants to be a player in the stock car world, if only it could find the money—which, the suit alleges, NASCAR kept it from doing.

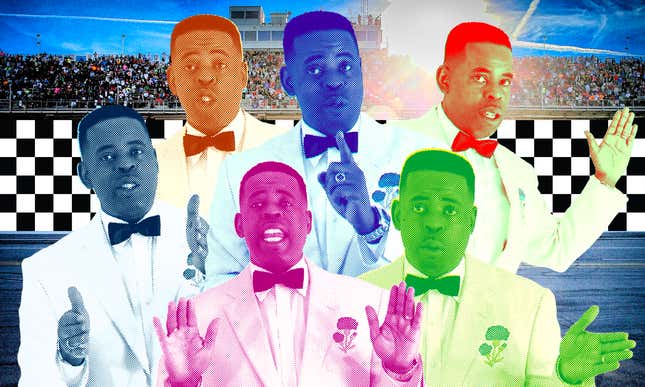

But Cox’s record of minority outreach in motorsports more heavily involves staging protests and trying unsuccessfully to recruit celebrity supporters—the latter with a bizarre series of YouTube videos full of get-rich-quick promises to investors, some addressed to celebrities the likes of Barack Obama, Kim Kardashian, and Bill Gates.

The lone racing team owner who partnered with Cox, and whom Cox cites in his videos, says they’re no longer together. Radio and TV host Steve Harvey, who was in talks to partner with Cox, has now publicly denounced Cox and the lawsuit.

Through the years, Cox’s program seems to have become mainly a matter of calling attention to NASCAR’s treatment of Cox’s program. In Harvey’s case, the celebrity said he was asked to support outreach to underprivileged children, only to learn that Cox planned to have those children block the road in front of Coca-Cola’s headquarters to protest the company’s NASCAR sponsorship.

NASCAR says it will countersue for defamation.

The Lawsuit

Cox’s lawsuit, which was filed on Sept. 19 in New York, alleges that NASCAR, its teams, and track operator International Speedway Corporation directed potential sponsorships away from his minority-focused team and towards established, white-owned teams instead.

This lack of sponsorship, Cox’s complaint says, effectively blocked Diversity Motorsports from participating in the expensive sport. These actions, according to Cox, reinforced the sanctioning body’s status quo.

Cox’s lawsuit also takes issue with the recently instituted Charter system, which guarantees 36 of the 40 starting positions for each top-tier Sprint Cup race to longstanding (read: predominantly white, in this context) teams.

Charter teams may sell their Charter entries to smaller teams; however, the suit claims that none of the established teams were willing to work with Cox.

Additionally, the lawsuit alleges that NASCAR would not work with any Cox on any programs to encourage diversity in NASCAR, including through its in-house Drive for Diversity program.

Jalopnik reached out to Cox’s lawyer Ronald Paltrowitz for comment, and he reiterated his client’s position that the charter teams, NASCAR, and ISC have discriminated against black people by refusing to work with Cox’s team. Paltrowitz declined to let us speak with Cox directly, and said he is handling all inquiries about the case on Cox’s behalf.

What Is Diversity Motorsports Racing?

Diversity Motorsports Racing sounds like a team name, but most of its work involved arranging for Cox to put the name of his group or its programs on existing teams’ cars.

The Diversity Motorsports website depicts a race shop in North Carolina, and the lawsuit lists as its principal place of business an address belonging to Bob Schacht Motorsports. But Bob Schacht, the shop’s owner, said that while he had worked with Cox in the past, they no longer work together.

In addition, Diversity Motorsports’ “Services” description is more about sponsorship packages than anything:

DMS is an asset holding company which creates brands and sponsorship opportunities for companies and global organizations which would not normally invest in the motorsports industry. We create racing team sponsorship packages, which include customized multi-race packages if an entire season sponsorship is not feasible for the sponsor.

A series of YouTube videos posted by the Terrance Cox Global Network made wild promises for Diversity Motorsports’ potential partners. Diversity Motorsports would handle the minutiae of running a race team, and partners, Cox argued, would get to sit back and enjoy the profits.

“Being that you’re such a large brand, all those millions go into your pocket from sponsors every year, year in and year out,” Cox promises in a YouTube video explaining how Diversity Motorsports works.

In reality, small race teams usually don’t turn a hefty profit. There’s a saying that the easiest way to make a small fortune in racing is to start with a large one, and it especially holds true for lesser known, less experienced teams. If the National Guard can’t get a good return on its NASCAR investment from highly patriotic NASCAR fans, a relatively unknown brand probably wouldn’t see much of a boost, either.

Cox’s sparingly viewed videos—most of which have fewer than 50 views at the time of this writing—didn’t get him the celebrity connection he wanted.

The brands that Diversity Motorsports Racing ultimately arranged to promote—with the exception of some funding Cox claims in the lawsuit came from the Church of God in Christ in Nov. 2010—weren’t previously established philanthropic groups, but rather, groups Cox described as educational and outreach efforts that he had started himself, bearing names like “Reach 1 Teach 1" and “Racing for Education.”

Finding evidence of Cox’s groups’ actual impact is somewhat tricky. GuideStar, a resource for information on nonprofit organizations, turned up zero records for any of the outreach efforts Cox claims to have led in his legal complaint.

When we asked his attorney, Paltrowitz, for some clarification on the groups’ activities and impact, he declined to comment, saying that they are matters that will be addressed in litigation.

A press release from Diversity Motorsports Racing posted on SB Nation ahead of the 2011 season touted the “team’s” signing of driver Mike Bliss. The group showed off a Racing for Education-branded Nationwide Series car at Daytona in 2011. (Nationwide Series was the name of NASCAR’s second-tier national series at the time, which is currently branded as the Xfinity Series.)

But according to Cox’s complaint, that car was owned by TriStar Motorsports. Diversity Motorsports’ Racing for Education effort was merely a partner that got a big, snazzy decal on the car. This was the only NASCAR national series car that our research could identify as having been backed in some way by Diversity Motorsports Racing.

In his complaint, Cox claims to have invested approximately $3.7 million in creating a racing team, and to have competed in “8 to 12 races annually” between July 2011 and 2015 in ARCA Racing, a stock car series that serves as a feeder for NASCAR.

While ARCA’s records do not list Cox as a team owner, if a partnership is running a team, its entries are usually listed under the name of a single primary owner. Schacht does appear in ARCA’s list as a team owner during this time period, but it is unclear based on team and sponsor names which cars may have been sponsored by Cox, and which were Schacht’s other entries.

Regardless, according to ARCA entry lists, all of Schacht’s entries combined didn’t run in anywhere near the number of races Cox claimed in the complaint to have participated in. Additionally, Schacht’s cars appear as “TBA” on the ARCA entry lists for four races in 2013, but ultimately did not start those races.

Furthermore, Diversity Motorsports Racing’s limited liability company was administratively dissolved on March 4, 2014, after receiving a notice from the North Carolina Department of the Secretary of State Corporations Division for a delinquent annual report in 2013, according to state records.

Cox’s attorney declined to clarify or comment on which cars Diversity Motorsports sponsored or ran in ARCA or NASCAR.

Schacht confirmed on a phone call with Jalopnik that he and Cox partnered together on the Diversity Motorsports Racing team, but Schacht said that it had only lasted a couple of years before the effort ran out of funding.

Schacht likewise mentioned that he was unhappy that the Bob Schacht Motorsports address had been listed as Diversity Motorsports Racing’s primary place of business in the lawsuit, given that he still fields cars in NASCAR and has no involvement with Cox’s lawsuit.

Cox’s Relationship With NASCAR Sours

While it is worth noting that minorities are often blocked from participating in existing institutions by being unfamiliar with how to begin working with those institutions, it seems as though Cox initially at least had some helpful contact with NASCAR.

Cox says in his lawsuit that he met with NASCAR representatives in 2009 about the series’ Drive for Diversity program. NASCAR’s multicultural development officers would not immediately agree to work with Cox, a relative unknown, in March 2009, so they gave him some advice on how to get started:

After Cox presented his business plan to [NASCAR Vice President of Public Affairs and Multicultural Development Marcus] Jadotte, he was advised by Jadotte that he start at the Go-Kart level and work his way up to the big cars and top racing levels, after which NASCAR would agree to work with him.

Karting is where many young racers get their start. Being told to start at the karting level is essentially getting told to work with the lowest levels of motorsport. NASCAR also told Cox that he was trying to duplicate many of its own Drive for Diversity efforts, which had been in place since 2004, according to the lawsuit.

Cox worked with The Pit, an indoor kart racing complex in North Carolina, as an outside contractor on marketing efforts in 2008 and 2009, according to owner Don Towne.

Towne said The Pit had a positive experience with Cox working on programs that brought underprivileged kids in to race karts and learn about motorsports, often from industry professionals themselves. Cox was only let go when the economy tanked in 2009 and The Pit could no longer afford to keep him.

Despite Cox’s claims that he found sponsorship for Nationwide racer Bliss, young oval racer Matt Murphy and ARCA stock car racer Ricky Byers—which we were unable to verify the details of, aside from the fact that the Racing for Education logo appeared of Bliss’ and Murphy’s cars—Cox’s complaint alleges that NASCAR officials still refused to work with him. (We attempted to reach Murphy and Byers to inquire about their working relationship with Cox, but did not receive a reply.) Perhaps NASCAR was hoping for more than Cox’s then two years of experience before entrusting him with a major outward-facing program.

Drive for Diversity business development manager and black team owner Max Siegel allegedly would not return Cox’s calls in 2011, according to the lawsuit. At that time, Cox claimed to be working on ways to fill the gaps where NASCAR’s Drive for Diversity program couldn’t offer help to minorities. (Attempts to reach Siegel for comment were not successful.)

While Drive for Diversity has helped minority racers like Darrell Wallace Jr., Daniel Suárez, and Kyle Larson get established, NASCAR could do a lot more in promoting the sport beyond its predominantly white base. That being said, Cox seemed unlikely to be the one to help NASCAR do a better job of supporting minority drivers and reaching out to minority fans. NASCAR refused to fund or support Cox’s programs, and the series eventually asked Cox to stop contacting them, according to the lawsuit.

Cox alleges that NASCAR promised to help find sponsors for his “Racing 4 Education” outreach initiative that launched in July 2011, but that those sponsorships never came through.

Cox’s Feb. 2014 video on the Racing For Education program.

Later Cox-led efforts were likewise allegedly discouraged by NASCAR. Cox’s complaint claims that sponsors, teams, organizations, and personalities including former NFL player Clark Haggans and the National Guard Youth Foundation were discouraged by the series from working with him at all.

Cox’s “Reach 1 Teach 1" program—another minority education and outreach effort in the same vein as Racing for Education—was apparently the last straw, prompting a cease and desist letter from NASCAR. Per the complaint:

On or about May 19, 2015, NASCAR’s Legal Department sent Cox and Diversity Motorsports a letter declining their offer regarding Reach 1 Teach 1, and directing Cox and Diversity Motorsports to cease all future communications with NASCAR, and informing them that all prior communications had been deleted from NASCAR’s records.

Despite this, Cox claims he tried to partner with comedian Steve Harvey on a racing team called “Steve Harvey 4 Education,” which ended predictably:

NASCAR advised Harvey that it would not sanction any race team associated with Cox and Diversity Motorsports.

On June 29, 2015, Cox was again told by NASCAR in-house corporate counsel Zachary Daniel to refrain from any future correspondence with NASCAR, according to the lawsuit. So far, Cox has refused to back down.

Steve Harvey—who was supposed to be the potential partner in Steve Harvey Races 4 Education—vehemently denied Cox’s claims on his radio show upon learning that he had been named in Cox’s complaint:

I don’t want no damn race team. I don’t even like fast-ass cars. I’m going to say it again... if that man [Cox] was going to mess around, I wish he had some money so I could sue him, but he ain’t got none.

Harvey said that he was originally approached by Cox about an outreach effort to get underprivileged youth involved with NASCAR, but Cox wasn’t initially up-front about his plans:

What [Cox] came to me was, what can we do to help youth? What it turned into was, he was going to boycott Coca-Cola and have all these youth come down there and block the streets in front of Coca-Cola.

When Harvey claims he found out that Cox’s protest plans would put the underprivileged children he purported to help in harm’s way on a busy street, Harvey broke off the deal.

When Jalopnik inquired about Harvey’s statements as well as the activities of Diversity Motorsports Racing and Cox’s outreach groups, Paltrowitz, Cox’s lawyer, explained in a statement that the planned activities surrounding Coca-Cola were a meant to be part of a “prayer intercession”:

I appreciate your interest in the lawsuit that Mr. Cox and Diversity Motorsports Racing LLC have filed in the Federal Court in New York against NASCAR, International Speedways Corporation and the numerous racing teams that are chartered by NASCAR. I believe that it is inappropriate to respond to your inquiries, as they involve matters that will be raised in the litigation, other than to say that we do not agree with Mr. Harvey’s characterization of the goals of the Coca Cola Prayer Intercession, or his denial of support for the efforts of Mr. Cox and Diversity Motorsports Racing LLC to establish a minority owned racing team.

Intercessory prayer is the act of praying on behalf of another’s needs—in this case, NASCAR’s alleged need to serve the black community better.

In addition to operating Diversity Motorsports Racing, Cox founded the Minority Youth Matters Movement to raise awareness of the fewer employment, driving, sponsorship, and educational opportunities given to minorities in American motorsports, according to ESPN.

The group’s most visible function, however, is protesting alleged discrimination in American racing, which it has been doing alongside Cox’s other efforts.

The Minority Youth Matters Movement frequently posts on various channels including Facebook and Twitter about alleged racism in NASCAR and IndyCar and has issued news releases about possible protests at racing events. As with the alleged planned protest in front of Coca-Cola, some of these are billed as “Prayer Intercessions.”

One Minority Youth Matters Movement press release from November 3, 2015, claimed that they would be moving forward with a class-action lawsuit in light of black driver Lewis Hamilton clinching his third Formula One world driver’s championship—a lawsuit that would potentially allege discrimination by the “International Speedway Corporation, NASCAR, INDYCAR, the Indianapolis Motor Speedway and several of their corporate partners, sponsors, affiliates and teams.”

“Once we begin receiving a list of names and discrimination instances, we will compile and categorize by type of complaint, so that we will have an idea as to how we move forward in the near future,” Cox said at the time.

The status of that case, or if it was ever filed at all, is not clear. (Cox’s attorney declined to comment.)

An Unusual Case

In response to this lawsuit, NASCAR has defended its Drive for Diversity program, calling Cox’s lawsuit a “publicity-seeking legal action” in a series statement:

NASCAR embraces all individuals interested and involved in our sport, whether as partners, fans, competitors or employees, and there is no merit to this lawsuit. NASCAR has a long-standing history of investing in diversity efforts including the NASCAR Drive for Diversity, NASCAR Diversity Internship and NASCAR Diversity Pit Crew Development programs. We established these programs to create opportunities for women and minorities, and embrace people of all backgrounds, within the industry. Diversity both on and off the track continues to be a top priority for NASCAR and its stakeholders. We stand behind our actions, and will not let a publicity-seeking legal action deter us from our mission. NASCAR not only will defend our organization against these meritless allegations, but we will be asserting our own claims against Mr. Cox for his defamatory actions.

Furthermore, black ESPN basketball analyst Brad Daugherty has a 10 percent ownership stake in JTG Daugherty Racing, yet JTG Daugherty is named as a defendant in the lawsuit anyway.

NASCAR currently only has one full-time black driver in its three national series: Xfinity Series driver Darrell Wallace, Jr. One Drive for Diversity graduate, Japanese-American Kyle Larson has made it into the championship-determining Chase for the Sprint Cup this year. NASCAR has also been the source of controversy over series CEO Brian France’s endorsement of presidential candidate Donald Trump and the series’ request to fans to stop flying the Confederate flag.

NASCAR certainly has a long way to go on how it deals with inclusion and equality. But this lawsuit’s focus on one man’s adversarial relationship with the sport does little to address that larger problem, and likely won’t help the sport move forward.

The full lawsuit can be viewed below.