You've Found A Mysterious Race Car Lost To History. Now What?

On the track, it racked up wins. Off the track, it racked up rumor. Its speed was a dream come true. Its handling could be a nightmare. And when the race car vanished, it became the stuff of legend and lore.

Many race cars of the 1950s and '60s were simply wrecked and scrapped. But when this one disappeared, its demise became the subject of much speculation.

"There's even stories that it went to the Pacific Ocean or a lake or something," says the car's body designer, Chuck Pelly.

Dave Helms, owner of Scuderia Rampante, a Ferrari restoration, repair, and aftermarket development shop in Erie, Colorado laughs about how little is known about the car, or what happened to it. "Nobody really knows where it is... For the most part, everybody believes it's gone forever. Not that it's going to be located, but that it's just destroyed and gone."

The race car is called the Harrison Special. It's not an artificial reef in the Pacific. It's not at the bottom of a lake. It's not a phantom only to be glimpsed in grainy photographs. The Harrison exists—a significant bit of it, at least.

Enough for it to be restored, rebuilt, remade. One of them. All of them. In part by one of its original creators.

Regardless of what may become of its future, it's the car's past that makes it so special. It was there as they built the lunar landing guidance systems. It was there as Carroll Shelby was working his magic on the early Ford GT40s. For a car that's spent so much of its time not being anywhere that people knew, it's a little remarkable just how many places and stories this car features in.

After I wrote an essay about his daughter, Jenni Helms, Dave Helms decided to let me in on a secret on the second floor of his shop. He pulled back the curtain—technically, a sheet—and there in front of me, an automotive skeleton in the form of a tube chassis.

Meanwhile, stacks of pristine, vintage Ferraris, Maseratis, Alfa Romeos and Porsches lined the back of the shop. Gleaming Dinos, Jaguars, and, of course, more Ferraris were parked on the floor beneath us. But here he was, showing me a chassis.

There in the presence of so many immediately breathtaking cars, Dave looked at me with an expression that said two things. The first, that this was what he was most proud of in his shop. The second, that I had no idea what I was looking at.

And he was right.

As I soon learned, these were the bones of a vehicle that has eluded collectors for decades, that has been the subject of countless stories, that raced, that won, that wrecked, that disappeared, that reappeared, that bonded Dave Helms with his now-deceased son, with his daughter, and even his own father. It also united Dave with a giant in the industry: Chuck Pelly.

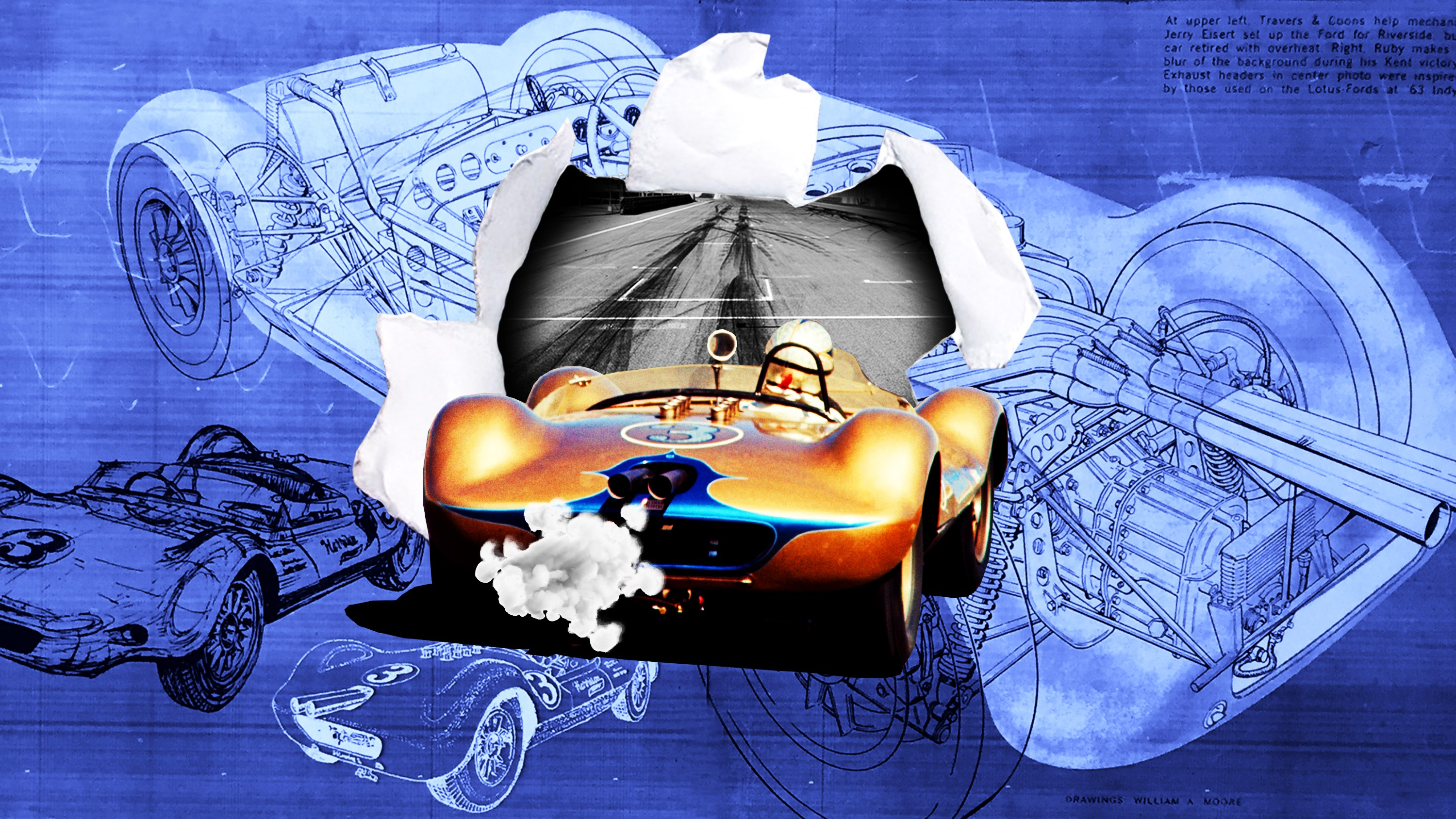

Now 80 years old, Chuck Pelly designed the Harrison Special when he was hardly more than a teenager. Despite his young age, and though it was among his earliest works, the Harrison Special was not Chuck's first project. After designing go-karts and dune buggies, he moved on to race cars.

"I would say, chronologically," Chuck explains, "it would go Scarab, Scarab II—the rear engine—and then Chaparral, then Harrison, and then parts of cars like GT40, the four-door Porsche, the four-door Volkswagen, 911 pickup truck," he says.

Chuck is no doubt proud of the Harrison. But throughout his life, he's thought a lot about that car, and as much as he recognized what he got right, he's also been bothered by what he got wrong. Of course, he never thought he'd have a second chance. He never thought he'd be creating it all over again like he'd done in the shop at Troutman & Barnes in 1962.

But that process—the restoration in which the past and the present meet, where the Harrison is reborn—is a whole separate story. This story is the story of the Harrison Special as it was, its myths and legends, its creators and caretakers. How it connects people, some family, some colleagues, some generations apart.

The Harrison Special was conceived when J. Frank Harrison took delivery of a Lotus 19 sometime in late 1960 or early 1961. The 19 was something of a phenomenon in that era. Originally designed by Colin Chapman, it was, unsurprisingly, a lightweight car with no frills.

"Colin Chapman had been trying to prove a point that power-to-weight ratio was more important than the entire package," Dave Helms explains. He says that Chapman "was well known for making what we refer to today as a supremely fragile car, extremely thin-wall tubing, no gusseting. If there wasn't a distinct purpose for a part on a car, Colin wouldn't approve it. He would have left it off because it would have saved weight."

As was befitting of a race car, the Lotus 19 had one purpose, and one purpose only: to finish the race more quickly than any other car on the track. "It might have broken in half at the end... But 'at the end' is the key," Dave chuckles. Because of this, Dave says, "The Lotus 19 took over the United States [racing] scene by storm... all of a sudden here comes a four-cylinder Lotus with an exceptional power-to-weight ratio that instantly dominated the scene."

J. Frank Harrison had been racing Maseratis with fellow driver Lloyd Ruby for a few years. In 1961, they'd entered an F1 car, but Harrison had his sights set on the ultimate road racing machine.

"J. Frank Harrison was a gentleman who loved road racing. In the early, early '60s, I think '59 to '61 or so, J. Frank Harrison raced Maseratis himself," Dave says. But it was a Lotus—not a Maserati—that caught Harrison's attention. And as it turned out Ruby drove a Lotus 19 in a number of dirt track races.

"He was able to see that a talented professional driver, with his [Harrison's] support and knowledge of road racing, would be the ultimate combination," Dave explains. So, he set to work on a whole new effort using the Lotus 19 as the starting point and enlisting Ruby as the driver.

As a successful businessman who made his fortune bottling Coca-Cola, Harrison had a bit of capital to invest. And with that capital, he lured Jerry Eisert, who'd been working on Dan Gurney's Lotus 19, and he brought the project to Troutman & Barnes, which Dave describes as "the premier race car designers and builders of the era."

This Culver City, CA-based outfit was where Pelly had designed the Scarabs and Chaparral—names that are now indelibly written in the canon of auto racing history.

Chuck is quick to point out that, even though Harrison and his Coca-Cola cash had funded the project, in comparison to the other teams and cars, the Harrison Special project operated on a shoestring budget. And this, he says, resulted in a lot of "bootlegging" when it came to doing the work and sourcing the parts.

And it's important to clarify what "designer" means here. For some of these one-off race cars, there are really two designers: the person who designs it from more of a mechanical standpoint, and the person who designs the body. In that way, Jerry Eisert was the mechanical designer, and Chuck Pelly was the body designer. As Dave Helms says, "Jerry doesn't give a hoot what the thing looks like, Jerry cares what it goes like."

Make no mistake, the Lotus 19 went fast. But not fast enough for the Harrison Special team.

The Lotus 19 was a four-cylinder, its powerplant being the Coventry Climax, originally designed for forklifts and fire pumps. When Jerry Eisert and the rest of the crew got a hold of the car, they figured—in true American fashion—that if the Lotus 19 was quick with a four-cylinder, imagine how it would do with a V8.

All they needed to do was get their hands on one.

That the Harrison Special sported a Ford V8 is well documented. What—until now—has been less documented is exactly which Ford V8 and where it came from. When I asked Dave and Chuck about this, separately, they each started laughing.

This is the thing about the Harrison Special. It's the starting point of a very great many stories—some that seem too funny or too unlikely to be true. But this, I'm assured, is the truth.

Jerry Eisert died in 2006, but Dave Helms spoke with him a number of times, in particular about the Harrison Special. "We became very, very fast friends on the phone, both enjoying the same thing—the racing. Jerry as a designer, myself as a mechanic, we found a great, great common bond. So a relationship had evolved to the point where I would call it a friendship. I cherished it as a friendship," Dave says.

And when Dave asked Jerry about the origins of the Ford V8, Dave says that Jerry went into a "gut-laughing stint," and said to Dave, 'Okay, I'm gonna share something with you.' He said, 'We had cut the back end of the Lotus 19 off right behind the rear bulkhead. We knew we wanted to run a V8. We didn't really have plans on what engine-transmission combination'."

Around this time, Dave says that Jerry Eisert was supposedly owed a decent sized sum of money by the one and only Carroll Shelby. Unpaid and in need of a drivetrain, Jerry and his team formulated a plan.

"They waited in the front widow at Troutman & Barnes, watching down the street until Shelby went to lunch," Dave explains. "As Jerry told me, they took a two-wheeler, walked down to Shelby's shop, grabbed the first engine that had a transaxle behind it, and two-wheelered it back to Troutman & Barnes. And I tell you, poor Jerry was gasping for air... telling the story, obviously, loving to relive it."

Dave continues: "As it turned out, it appears they took the engine and transmission out of the first GT40 that Shelby had in the shop at the time—Colotti transmission, Colotti Type 37 Transmission was quite rare, they made very few of them, and that's what went into the first half-dozen GT40s."

Shelby is deceased, which makes this tale even more difficult to definitively confirm, but it jibes with what Chuck Pelly remembers. He corroborates the story, and does so gleefully. "Yep, that's what I remember! I remember kind of wheeling a bunch of metal down to the local other shop," he recalls. Then he takes on the voice of Jerry Eisert: "'Just keep it down there for a little bit, Chuck, because so-and-so is coming by the shop.'"

But Chuck had far bigger jobs than simply hiding the swiped metal. His job was to design the body of the Harrison Special. He'd already created the now-famous Scarabs and Chaparral, and he had a strong sense of how he wanted the body to work. Chuck says, "the whole idea was to pull the skin very tightly around this, by our standards now, rather big car."

In some ways, he looked at the Lotus 19's original body in the same way Jerry looked at its guts. Specifically, he wanted a complete overhaul. "I'd come every second I could come into the shop and say, 'Throw that ridiculous body out! That's nothing. We want to make it new and nice.'"

So they did, and started from scratch. Far from wind tunnels and CAD drawings, the design process was far more organic. First, there was a sketch, which took Chuck all of one hour to make. From there, he explains how it went: "It was simply big pieces of plywood put on the floor, and the center lines of the wheel [and] basically where the driver would sit." But instead of calling Lloyd Ruby in for that part, Chuck brought in racer Chuck Daigh. "In this case, you know, we measured Chuck Daigh and stuck his butt in the car."

Pelly held Daigh in high regards, so it's little surprise Pelly envisioned him being the one to race it. "Chuck Daigh was my hero and by far the best driver, really the key driver for the Scarab cars," Pelly wrote to me over email. He went to say that Daigh was also "a very capable engineer," and he remembers that "he always teased me and called me Charlie. I said he had a lead butt because he went so fast."

Ultimately, though, Pelly says, "to my knowledge, [he] never drove the [Harrison Special]."

The rest of the car was designed to work in concert with Jerry's demands: Fenders and wheel wells were determined by how big they wanted the tires, and how much travel they wanted the suspension to have.

Then, Chuck says, there were "the clearances of the carburetion, the engine clearance, and the radiator. And then long strips of wood were simply cut out with a bandsaw and held to these points by people's feet and an old pencil following the curve of the piece of wood. What this crudeness did is made this beautiful, accelerated curve all over the car. You didn't lie. You didn't cheat."

With this skin-tight, honest design complete, they built a wooden buck upon which the sheet metal could be hammered out and shaped.

Such work—hammering aluminum—requires a high degree of skill. "Troutman & Barnes had a very, very close partnership with a team called California Metalcrafters, a group of exceedingly talented Argentinian guys. So after Chuck draws something, you've got the panel-beaters," Dave explains.

Chuck illuminates the nuances of working with aluminum: "When the aluminum panels come back, they come back in pieces like big potato chips. And these big potato chips can now be manipulated and pulled tighter or looser and held by Kenco clamps. So now you're working with an actual formed pieces of potato chips to mold the aesthetics of the curves and the functions of the curves."

And this must be done by the deft hand of a knowledgeable worker. "The beauty of making cars in these days out of hammered aluminum," Chuck says is that it, "brought a new honesty of form because if a sheet of aluminum doesn't like what you've done to it, it resists and twists back. So you sort of learn what a sheet of aluminum can and can't do. And you should be respectful of it, or it'll bite you."

He adds: "I think many of the cars of that period show a lot of biting of the users."

The Harrison Special made its debut at Kent in 1963 with Lloyd Ruby behind the wheel. There, it won a United States Road Racing Championship event. From 1963 to 1964, Ruby raced the Harrison Special aggressively. The V8-powered Lotus quickly gained a reputation for being fast and terrifying. On one message board dedicated to vintage race cars and their drivers, one poster wrote: "Lloyd Ruby is quoted as saying that this was the scariest car he had ever driven. The lack of down force made the nose and the tail lift, making driving a very hazardous business."

Chuck himself says, "You know, I should have lifted the tail a little," but perhaps what was most frightening was how the car could feel like it was going to come apart through the turns.

In fact, it's a wonder it didn't.

"Well, that was a point that I discussed with Jerry in a couple conversations that quite frankly terrified him," Dave says. "When I was doing the forensics on all of the bent-up old parts, I asked Jerry, 'Why is it that you chose to use electrical conduit for the rear framework?' And he just was appalled that I would suggest such a thing."

Electrical conduit, to be clear, is the tubing that wire runs through. It's certainly not a structural material.

Dave explained to him that he "found... parts that were undeniably gas-welded that were original to the car." He describes what happened next in that conversation: "all of a sudden there was a long, long pause. One of those uncomfortable pauses that feels like two minutes but is probably ten or fifteen seconds, and he said, 'I remember.' He said, 'We ran out of time. We were using conduit to mock up the frame when it was sitting on the frame rack at Troutman & Barnes. We set the engine in place, and we started using electrical conduit to mock up the framework, ran out of time. We welded the damn conduit together.' And that's what Lloyd Ruby was tasked with driving. The fact that he won his first race that he entered with it that way was a testament to Lloyd's abilities and yet a miracle that it held together to that end."

"Yep, that's right," Chuck remembers and laughs. "Conduit. Electrical conduit."

Dave is a purist, but this is one of the only things he sought to change. "It's one of the few modifications that I have made to the chassis throughout the restoration process. I have held true to the smallest detail in that process, but I asked Jerry's blessing on allowing me to use 41-30 alloy tubing, a thin-walled chrome-alloy tubing, in the restoration of it because I'm certain that's what Jerry would have done. And Jerry was quite frankly rather appalled that I would even ask his blessing on it. But he granted it."

No wonder, then, why back in 1964, Chuck Pelly says that the legendary racer Jimmy Clark "did not want to touch it." But, as Clark was sponsored by both Lotus and Ford, he was encouraged to drive the car.

He did in the qualifier, and with the Harrison Special it put him on the pole at Mosport. But after that, he refused to drive it, fearing the car simply wouldn't be able to finish out the race intact. It had been on the circuit for a year and a half. For any race car (let alone one finished with electrical conduit), this was a long lifespan.

"I think people just figured that a race car had a lifespan of one year," Dave explains. "And by that point in the '60s, things were evolving at a breakneck speed. I mean race car designs were completely changed in the course of six months. A race car that was a year old? That's an old race car."

Still, even after Clark's turn in the Harrison Special at Mosport in 1964, the Harrison Special went on racing. Drivers Charlie Kolb, Jef Stevens, and Orly Thornjso being among the car's drivers.

Stats are difficult, if not impossible to verify, but it's been documented to have been raced through 1966. Dave Helms estimates it probably raced in "two dozen" events in its lifespan—some minor and having no written record. The website RacingSportsCars.com compiles data on cars, and it lists the Harrison Special as having raced in 10 official events, boasting an impressive two wins and two third place finishes.

The car changed owners frequently throughout the '60s, at some point getting blue and gold paint over its original aluminum exterior. It was moved around throughout the country. Minnesota. Aspen, Colorado. And then either Nebraska or Kansas. And this, Dave says, is where the Harrison is said to have raced its final race. "My understanding," he says noting he has not been able to verify, "is that it slid sideways into a tree and broke in half."

From there, the wrecked Harrison Special was purchased by a collector and held until the day Dave Helms opened Scuderia Rampante.

But before he did, it turned out Dave's own father had time with the Harrison Special. One of the car's drivers, as previously mentioned, was Orly Thornsjo. "I had heard the name many, many times when I was racing in the midwest and we lived in Minnesota, but I could not place it," Dave explains.

So, he says, "I called up my father who had crewed for me when I was racing, and I asked dad, I says, 'The name Orly Thornsjo mean anything to you?' And dad instantly said, 'Of course! I worked for Orly for twenty years!' I said, 'At Honeywell?' And he said, 'Yeah.'

As it turns out, Dave says, at Honeywell, Orly was "the lead design engineer, he was the team leader for the team of engineers that were tasked with designing and developing the lunar lander guidance system for Apollo 11. And eight months behind on the guidance system design, Orly would bring that Harrison Special race car into Honeywell every Friday before a race. He would pull all of the engineers and the technicians off of the Apollo project and put him on his race car in the parking lot."

And then, the light bulb bulb went off. "Dad asked me, 'Is that thing blue and gold?' I said, 'It is.' He said, 'I worked on that car when you were a young man.'," Dave recalls his father saying.

And here, he pauses to reflect. Dave is not only a mechanic, but a forensics expert when it comes to the Harrison Special and other exotic and rare cars. But what really seems to have him struck are stories like these.

"Priceless, priceless stories," Dave calls them. "It's a car. But when it's a car that has a connection to one of the greatest times in our country's history, the moon landing, I mean, who could have predicted that of a car? I'm a story collector, and I think that's every bit as important as the mechanical aspect of the car," he says.

And it's an an aspect that doesn't require oil or welding, restoration or rebuilding. It just needs retelling to keep it intact.

But still, Dave has been intent on restoring the car, keeping it faithful to its past, and keeping it in the family.

It was nearly 40 years later when Dave Helms—already an experienced mechanic on English and Italian sports and race cars—decided it was time to hang his own shingle. He and his family had already been living and working in Colorado, so he had cachet, especially with local car collectors who were eager to give him business.

In 2004, he opened up Scuderia Rampante in Boulder, Colorado. A collector who owned cars that Dave had worked on previously was his first customer. And though Scuderia was a decidedly Ferrari-focused shop, his first job was not an Italian car.

"The Harrison Special," Dave remembers, "that was repair order number one." And as it turned out, the customer declared bankruptcy shortly thereafter. Dave took a lien on the car, and then took possession of it.

Throughout our conversations, it's a fundamental fact that Dave himself is the current owner of the Harrison Special. But this seems like a foreign concept to Dave. I ask him: Who's the owner of the Harrison Special?

"History. History owns the Harrison," he answers.

Later, I attend a meeting at the shop with Dave, Jenni Helms, and a handful of Scuderia mechanics. It's partly about planning, partly about brainstorming, and everyone's upbeat and busting each other's chops as they work. But when one of the mechanics refers to it as "Dave's car," Dave turns serious.

"That's not my car," he says, and makes sure we all hear it.

Back at his house, built into the sweeping mountains of Lyons, Colorado, I ask Dave to pin it down for me: what is his current relationship to the Harrison? "Currently, I'm a caretaker of the Harrison Special. But the Harrison is bigger than I am," he says. "That's all I am. I'm the mechanic at this time. I'm putting it back together. 'Caretaker' may be giving me more credit than is due. I'm gluing it back together."

That his father had helped glue the Harrison Special back together in the mid-'60s was a surprise. But there was someone else in the Helms family who was helping Dave glue it back together when Dave became the caretaker: Dave's son, Bill.

"My son and I worked together on that car quite a bit... My son was my fabricator, machinist, and welder," Dave explains.

Bill wasn't much for tuning engines or cam timing. ("As we know from before, cam timing is my thing," Jenni says, referring to the story I wrote about her, which was published earlier this year.) What Bill had was an uncanny knack for working with metal, and it went beyond mere fabrication.

"Any part that was still salvageable we were saving. But if it was damaged beyond re-use, Bill would come in and we'd stay 'til the early morning hours during the week, he'd stay all weekend, and I'd come in on a Monday morning, and there'd be thirty pounds of metal shavings on the floor," he remembers fondly.

Dave says that Bill wasn't content with simply recreating a part. Instead, Dave says, he would, "[experiment] with the mill and the lathe on how to make that part in the same manner that Jerry did back in the day. He would look at the toolmarks on that part and he would try to replicate those toolmarks on the lathe or the mill, and often a combination of the mill and the lathe, down to the point where he could replicate the feed rate of the tool marks on the part."

Dave smiles and sums it up for me: "Sheer brilliance. He was building, he was restoring and building these parts with the same passion, exactly the same level of passion as Jerry Eisert built it originally."

But Bill died in 2017. And over the years, Dave has always been careful to never rush the work on the Harrison Special. "It's been hidden away and worked on little by little over the years," Dave says. "Any time I feel hurried or rushed, it would get mothballed again until I was relaxed and could go slow."

But despite the loss of his son, he's not going it alone. Jenni left Scuderia in the early summer of 2018, giving up her hard-earned title as foreman mechanic. But as history has shown, the Harrison is bigger than things like who-works-where, and there's a lot of family history there. So, she's stepped in to work alongside her father on the car.

"I'm in," she tells me seriously. "When I'm in, I'm in. I'm in."

But there's someone else who's in: one of the car's original designers, Chuck Pelly. Last year, Dave hosted Chuck at Scuderia (now relocated to Erie, Colorado), and they pledged to resurrect the Harrison Special together.

Their admiration for each other is both abundant and obvious. But as they set to begin the project, they are aware of some of the tension that may lie ahead: Dave is a student of history, a purist. To him, the imperfections of the Harrison Special were part of its past, its glory. Where the lines were slightly misaligned is where the stories of small budgets and last minute changes lived. Those are what the made the Harrison Special, well, special.

But for Chuck, the Harrison Special was good, but not as good as it could have been. And while he appreciates the history, he's not a historian. He's a designer. And, as Chuck says, "as a designer you're never done, you just want to keep tweaking it."

I tell him my view on the project: that for a car like the Harrison, there is no singular "way it was." The car was always evolving, changing, being tweaked. To restore is to choose a moment in time. But which moment, who's to say? Dave wants to go back to 1962. Chuck is always looking toward the future. Chuck laughs heartily. "That's wonderful! I'm so happy you said that!"

Chuck says that he is, "absolutely on the make-it-better [side]. Yesterday was yesterday. To have to remake that and get authorization on the crappy weld that was done there and to put on these old fashioned drum brakes, it kills me! And of course, ergonomic human interface, there's no room for your left foot. You gotta kind drive with your leg up in the air. But, I have judged a lot of Concours and I keep fighting for, you know, people taking the past and making it as beautiful and technically proficient. But then it's balanced by the people who want to respect tradition and keep things as a reference of the past. You can argue it's a two-sided argument. But I'm definitely on the change-it side."

When it comes the question of pure restoration versus perfection, Chuck and Dave understand it's their will against the other's. But there are bigger factors that drive their decisions: by perfecting it, does it rob the Harrison of its past? And even more practically speaking, does it rob it of its value?

Indeed, there is a very large financial aspect. To restore the Harrison Special is expensive. Being the caretaker is costly. So when the project is done, the Harrison Special will have to be sold. And for it to be its most valuable, it cannot be a new version of an old car. It must be a restoration. Chuck is well aware of what's at stake.

"You know, we're talking about a lot of money. That car on the market now if it's accepted and it runs a couple races, it can be in over 20 million dollars," Chuck figures.

Dave smiles at what lies ahead. Not just stories of the old days on the track and in the shop, but real work, hard work. Some with a car called the Harrison Special. And some with its original designer, who is eager to make every line meet just as he'd always wanted it to.

"I'm not gonna let him correct 'em," Dave tells me slyly. "It'll be the clash of the titans, fifty years later. It'll be priceless."

David Obuchowski is a writer whose essays regularly appear in Jalopnik. He's also the host and writer of the podcast Tempest, the first season of which is available where ever you get your podcasts. His work has also appeared in The Awl, Longreads, SYFY, Deadspin and other publications. Follow him on Twitter at @DavidOfromNJ.