How Jenni Helms Survived Tragedy To Stay Ferrari's No-Comeback Kid

We can quantify so many things in the automotive world. Quarter-mile times, points in a race, engine displacements. But how do you measure the greatness of a mechanic? How do you quantify that? Is it how quickly they can fix a vehicle? Is it how many vehicles return to their shop for do-overs or further repair, known as "comebacks"? Is it their ability to bring something back from the brink, even when it's extraordinarily complex?

What makes Jenni Helms, the shop foreperson of Erie, Colorado-based Scuderia Rampante, such a great mechanic is all of those things. And so much more: passion, dedication, and survival.

For Jenni, 32-year-old daughter of Dave and Kris, the founder-owners of Scuderia Rampante, Ferraris are family, life, light. They are her family's past, present, and future. Theirs is a business that sells, services, and restores. They also make their own high-end aftermarket parts for the cars.

Jenni supervises four other mechanics and works tirelessly with her father, Dave, to create, improve, and expand on what they do. One of the best Ferrari shops in America, Scuderia Rampante has a waiting list to even get in, and Jenni is at the heart of it all.

For her, Ferraris are more than just cars—they are the constant, even in the chaos.

And there has been chaos—in the span of just a few months, a medical emergency, a frightening injury, and an agonizing family tragedy. Almost exactly one year ago, the unthinkable happened to the Helms family, costing them one of their own.

But they have persevered. And Jenni has more than merely survived. If her father is right, she is on the cusp of greatness. Certainly, more than she is willing to admit.

I met Jenni late in the evening at a taqueria in Lyons, Colorado. I shook her hand, which was stained black with grease and oil. "This is clean for my hands," she said, though not self-consciously. "You would ask me why I didn't wash my hands, but honestly I scrubbed them for probably two minutes."

Because her father has been a mechanic for 40 years, she's been around cars her entire life. "I just remember always being around cars and my dad always working. His hands always looked like this," she told me, displaying her fingers. "As a kid, I couldn't understand why his hands were so gross all the time. But now I understand. It's in our nature."

The night I met Jenni in Lyons, I found her sipping a beer at the bar. The weather had conspired to make the meeting happen. A Scuderia client in Nebraska wanted some work done on his Ferrari 328, specifically to the vehicle's fuel system, so Jenni packed her tools and was ready to hit the road, but the forecast warned of severe snow along Interstate 80. With plenty of other work to do, she delayed her trip a few days and took a rare break from work to meet with me.

It's not unusual for a good Ferrari mechanic to cross state lines for their clients. And the truly good ones are a rare breed. I spoke with Erik Chovanetz, owner-operator of Ovilla, Texas-based MC Bodyworks, which customizes classic muscle cars, about how working on these cars differs from wrenching on more ordinary vehicles.

I asked Erik how difficult it was to become a quality Ferrari mechanic. "Oh, it's extremely difficult. Extremely. Ferraris are so fine-tuned, you have to be one with the car. Not many people can do that," he told me.

No surprise then that Scuderia Rampante's clients are loyal, know them personally, and span the country. When I visited Jenni at work, she showed me one of the drawings that clients' children have drawn for her, depicting her as a happy stick figure standing among her family members and, of course, a Ferrari.

For how rare it is to find a great Ferrari mechanic, it's rarer still to find one who is a woman. Jenni is one of the only women at her level in America, and indeed the world.

I spoke with representatives of various Ferrari service shops on background, and many told me flatly they had never heard of a female Ferrari mechanic. Erik Chovanetz, who spoke on the record, told me that even in this already male-dominated field, a woman at that level is "Very rare. There are some that are out there, but it's one in a million."

Maybe more than one in a million here, since Jenni is not only the main mechanic and shop foreperson, but knows all when it comes to their products, including their triple-ply silicone houses and the SRI Gold Connector Kit, of which she is their expert installer. "In house, with the engine out, I can do one in 10 hours," she said, referring to replacing every terminal connection of a Ferrari's engine management system.

But Jenni's favorite thing to do is cam timing, a process by which she perfectly tunes the engine so the cylinder pumping action is optimized, and the exhaust and inlet valves open and close at perfect intervals.

Cam timing can be complicated with any vehicle, but with a delicate but powerful machine like a Ferrari, it's on a whole other level. I asked Erik to compare cam timing on an everyday, regular car's engine to a Ferrari's, and he said, "Good lord, that's like playing a fiddle and playing a violin. It's one extreme to the other."

Maybe that's what makes a great mechanic—when they see tools and parts no differently than musicians see instruments, or painters see watercolors, oils, and gouaches. "I see cam timing a Ferrari as an art," Jenni told me. "It doesn't matter vintage or current production. Cam timing is the heart and soul of the entire engine."

She first learned about cam timing from her father. The father's footsteps in the Helms family are big ones. Dave Helms knows all about that himself.

"Dad was an aerospace engineer tasked with the guidance system controls on the lunar lander on Apollo. Then he was on the SR-71 before that," he told me. "So, I mean, he was at the pinnacle."

Dave sought a similar path and went to college for electrical engineering. But times had changed. Dave said he "figured out way late in school that I was going to be stuck on walk-in refrigerator controls for the next 30 years because of the way aerospace shut down." So he pursued a passion: fixing cars. Ferraris in particular.

Along the way he married Kris, and they had three kids: Nikki, William, and Jenni. Wanting to own his own business, he opened up Scuderia Rampante in Boulder, Colorado.

"We had $10,000 in our bank account and we opened Scuderia in Boulder, and that was it," Kris said. That was in 2004. Today they're in a 30,000-square-foot building with a waiting list to get in.

Dave is matter-of-fact about what he's built, in particular with Jenni. "Already, Jenni and I have come to be known as the janitors of this industry. A lot of times when people have worked on a car and they can't get it right, they'll send it here. That's both a blessing and a bane because I waste a lot of time. I can't bill for figuring out some of these tough things. The blessing is that we don't give up, we always succeed," he said.

Maybe that's what makes a great mechanic—succeeding where others don't.

Jenni said she and her father "have studied every aspect of cam timing... We fight hard to get the timing spot, which, by the way, is not always factory spec. Engines that leave our shop fall into timing, rather than out... I can spend hours matching the second set of cams to the first, changing the pins from one position to the next. I have spent some days with tunnel vision, and wiping sweat from my forehead to perfect this."

Jenni and her father are a good team. And when her brother, William, worked at the shop he brought his own talents to Scuderia Rampante.

William was good at wrenching, but it was not his passion like it is for his sister and father. Even as kids, Jenni and her sister, Nikki were racing and fixing up their quarter midgets. William was playing in the dirt, trying to catch bugs. But he had a love—and a knack—for creating, for crafting. Dave recognized this and made him Scuderia's welder and fabricator. And with that, he found his place at Scuderia right alongside his father and sister.

"He was perfect at it," Jenni explained. "You could just hand him anything—a chunk of metal, a chunk of aluminum or steel, and be like, 'We need you to go build this part.' You'd give him a little instruction, and he could go build anything. He was a genius."

Jenni was insistent about just how brilliant her brother was. She called him the "smartest man ever," and said that his knowledge and skills were nothing short of "amazing."

An avid outdoorsman and angler, William was rugged and lean. He was taller than his immediate family members, and, as Jenni eagerly pointed out—and it's evident from the photos she showed me—he was "such a good-looking man." She acknowledged that might seem a little strange "for a little sister to say that about her brother," but she insisted, "He was very handsome."

She likes talking about William, how good his welds were, how he could anticipate all possible failure points of things he fabricated. How at home he was in nature.

But Jenni was in good spirits for another reason the night we met. "We finally, this morning, got the go-ahead," she told me. Her boss—who's also her father (though she never calls him that when referring to anything work-related)—told her to go ahead and pull the engine on a Ferrari 348.

"That's a twinkle in my eye," she said.

It's been a long time since she's been able to smile like this. Referring to March, April, and May of 2017, Jenni told me, "I was on a bad streak, a very bad streak."

In March, William took his own life. She wanted to tell me about that. But first, she wanted to tell me about April and May.

In April, she was hospitalized for kidney surgery. She had already been stricken with kidney stones the year before. But in April, things were dire. She collapsed in agony, and was rushed to the hospital. "I had both kidneys shutting down," she told me. "It was kidney stones blocking my ureter. If I wouldn't have gone into the emergency room that morning—that pain with the kidney stones—my kidneys would have failed."

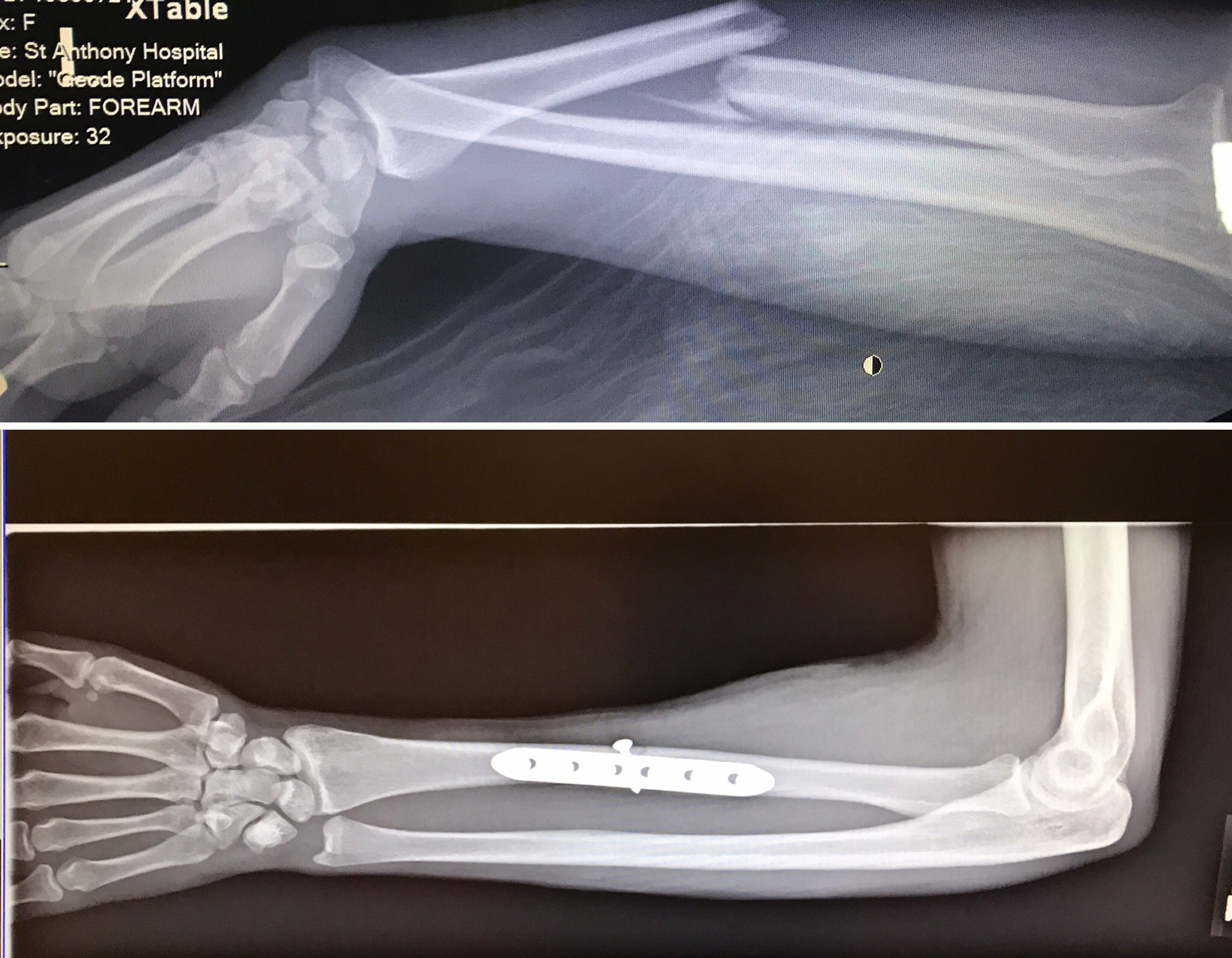

But they didn't fail. She underwent emergency surgery, and she recovered. A month later, she was back to skateboarding. Unfortunately, that's when she dislocated her wrist and snapped the bones in her arm. (Yes, she went skateboarding right after nearly dying in a hospital, because that's Jenni for you.)

Jenni skateboards for fun, but for Jenni, even her recreation is technically work, because in addition to being the head of Scuderia service, she's also a semi-professional skateboarder. She had been skateboarding since she was a kid, but 10 years ago, she got serious, and the Original Betty Skateboarding Company took notice, and signed her to their roster.

Jenni's favorite way to skate harkens back to the old school. "As a skateboarder, I like to skate pools that are not made to skate. Actual pools. Swimming pools. Like the Lords of Dogtown, the way skateboarding was originally done," she explained. That's what she was doing with her friends on Memorial Day weekend of 2017. But on her last run, she told me, "I was just getting too tired."

She hit a small "hip" at the deep end of the pool, and it rocketed her 8 feet back toward the shallow end. "I flew, and I put my arm down to catch myself. And I just snapped my arm in half," Jenni said.

But Jenni is not big on pity. "I'm like, 'I'm fine! I'm fine!... Keep skating," she remembers telling her friends. "And then my friend Alex...he kept looking over at me. He was like, 'Let me see your arm. I know you're hurting.' I'm like, 'I'm not hurting, I'm fine, I'm fine!' And then finally, I pulled it out, and my wrist was dislocated, and then this arm was just snapped in half."

Alex is Alex Buncy, 26 years old and also a professional skateboarder. A friend then, he's her boyfriend now. He'd been there for her the previous month when she needed emergency kidney surgery. And he was there for her in March when her brother died.

Alex carried her to the car and brought her to the hospital, where they put her in a temporary cast and told her to come back two weeks later so they could implant a metal plate into her arm.

Jenni wasn't eager to phone her father with the news. "I didn't tell him at first," Jenni admitted. "I couldn't. In the hospital, Alex wanted to call my parents, like 'They need to know.' But...I was like, 'Don't. I don't want to call them. I'm terrified. No. I didn't want to tell them their foreman mechanic just snapped her arm skateboarding.' "

She told him what she did, and his response, she said, was, "You [still] got a right hand... [On Tuesday], show up to work. Put a bag over your arm so you don't get it full of oil and grease, and come to work."

I winced at the remark. But Jenni was unfazed. "Work is in my nature. It's natural for me. If I take time off, it's odd. It's a guilty feeling," she told me.

Yet Jenni was relieved to get back to the shop. "I'm going, 'I should be working. What am I doing?' " Sure enough, that Tuesday, only two days after she snapped her arm in half and dislocated her wrist, Jenni said she "got into work and showed up with this huge temporary cast. I cut up a pair of Spandex or yoga pants and put it over my arm, and then I just showed up. No one talked about it. I had a cast and I was like, 'Don't talk about it. Don't talk about it. Let's just work and get shit done, it's no big deal.'"

With one arm, and in a bad streak, she still did her job. No comebacks.

Jenni says she can drop the engine of a Ferrari 348 completely by herself in no more than two and a half hours. Still, she's a big fan of working with the team of mechanics she supervises.

"When it comes to pulling an engine out, I'm not too heavy," Jenni explained, "and I'm flexible. I can crawl up on top of the engine. I know where the support and the subframes are. I can sit on top of the engine to do all the work from on top. We raise the car up and all the guys can go from underneath, and we drop the engine, and I'm the girl sitting on top of the engine."

I came into Scuderia Rampante to watch her work, and she was eager to show me the 348 engine that she pulled the morning after our first meeting. It was hooked up to something she developed with her father: the Evoluzione Run-In stand, an engine stand that has a fuel pump, oil pump, coolant pump, and more. It allows them to pre-warm the engine so that its components can expand, and then fully test and monitor the engine without reinstalling it in the vehicle.

She was working with Travis, one of her mechanics, completing some final electrical work. She supervised as he attempted to fit a connector. Something about it wasn't quite right to her eyes. Ever the perfectionist, she told him to stop, and that she was going to use a whole new part. He nodded.

She showed me around, introducing me to her two bosses: her mother Kris, and her father.

"We're very, very close. We're more friends. I'm not her boss even though I am her boss," Kris told me. Kris is the office manager, and does all the daily bookkeeping, though she's very well acquainted with cars as well.

But now, as office manager, she watches her daughter work. And she noted, "Jenni doesn't have any cars that come back where the work has to be redone. Since we've grown, we've gotten a number of them back, none of them ever being real bad, but still," she sighs to indicate, it's a frustrating reality of working with a larger staff of people.

"Not to make Jenni shine, but she hasn't had any comebacks."

Dave Helms confirms this. "She has no comebacks. When that [car] goes away, it's done. It's not only done, but it exceeds everybody's expectations on what it is."

These are not the words of a father who coddles his daughter.

Dave laughed when I asked him this. "She gets no slack. In fact, she's held to a higher level than the other guys. Because you've got the proud father whose expectations are very, very high. And I'm not just a proud father, but I can't have her gaining the shop owner's daughter slack, because that loses the respect of the crew. Yes, she is undoubtedly held to a different standard. And part of it is a protection for her, and part of it is a father wanting to see her excel."

And he admits, though not shamefully, "pushing too hard is often a thing."

As their kids go, Dave is correct to say that it's just Jenni in the business now. Nikki left Scuderia Rampante and the industry as a whole, in part because she was involved in a car accident that resulted in back pain, which has made it difficult for her to work on cars. But also because she has different aspirations, such as organic farming.

William's path ended in March 2017.

Jenni says that even when she was in high school and he was in his 20s, he struggled with alcoholism. He would move in with girlfriends, then resurface needing help, needing money. "He was always in and out. He'd work at the shop for months at a time. But then he'd disappear for a while so he could go on a drinking binge or run off to his girlfriend's house. We were always there for him every time."

When Jenni was 25 years old, William was just completing a rehab program in Pueblo, Colorado. "I picked up from rehab when he was all done," she recalled. "And he was like, 'I need a place to live.' " Turns out she did, too, so they got an apartment together. But it wasn't just a matter of good timing. "I wanted to make sure he stayed sober," she told me. "I'm his little sister."

But she couldn't, and she blames herself. "I got caught up in my own life. I didn't keep an eye on him. I wasn't there for him the way I should have been."

Jenni says some evenings, she'd spend time with other friends instead of William (or Billy, or Bill, as she frequently refers to him). Or, rather than go fishing with him, she'd go skateboarding instead. "I wasn't there the way I should have been."

Jenni says that, "In retrospect, he shut down. He was just kind of like, 'Fuck it. I got no one.' And he started drinking. He went through his relapse and was drinking again."

So when Jenni bought her house on the top of a mountain in Lyons in the early summer of 2016, she implored her brother to come up and hang out whenever he wanted. "I would always make sure there was no beer in the fridge, no alcohol out." He often did, and she said, "he was like a kid in a candy store."

But he wasn't living with her. Instead, he was splitting his time between a fifth-wheel trailer parked at Scuderia and his girlfriend's house in Arvada. That's where he was at in early March 2017, when Jenni said William's girlfriend called Kris at work.

It was William's last day of probation. All he needed to do was make his final meeting. Instead, he'd locked himself in the trunk of his car. "I'm like, 'What the fuck? It's his last day, they're gonna set him free! He's been so good! What's going on?'" Jenni remembers.

So Jenni and her mother sprung into action. "I just ran up to my toolbox and I grabbed a pry bar, hammer. I just grabbed tools."

Once they arrived at the house, Jenni said, "My mom's knocking on the trunk, talking with him, going, 'You're my son, I love you, I love you. Come out, we're gonna take you to probation, it's gonna be fine.' Meanwhile, I'm on the passenger window, behind the passenger seat window, trying to pry the window down."

And then, Jenni remembered, he opened the trunk "and he just looks fucked up, not sober at all... He's all confused, 'What are we doing? Where are we going?' I was like, 'Me and mom are taking you to your last probation meeting. Everything's gonna be fine.' I'm trying to be optimistic."

Jenni said, "it was really odd because...halfway between Arvada and the Golden courthouse, he started to sober up and talk normal and talk intelligently and talk like what I knew him to be." Then she asked, genuinely perplexed, "If you're that drunk, how do you sober up that fast?"

As they waited for the meeting, Jenny continued trying to comfort her brother. "I kept telling him, 'It's gonna be okay, we're here. We're you're family. Me and mom are here'."

Somehow, William made it through his meeting. "He walks through the door and he's just—oh my god. He was just smiling huge. He walked through that door, and he had just the biggest smile on his face."

They took him to dinner. "And he was just telling me...'You know, it's different. I'm off probation, Jen. I'm off probation. It's different than all the other times. I'm gonna do good. I'm gonna get my shit together.' Like, he was gonna do it, and I believed him," Jenni recalled.

Right there at dinner, William agreed to go into treatment. But first, he told his mother and sister that he wanted to clean up the trailer he'd been living in off and on. It was a plan. And Dave immediately arranged for his son to enter what Jenni describes as "an amazing treatment facility in Kansas."

During the next few days, William was supposed to be cleaning out the trailer, but Jenni didn't see him. She said everyone seemed nervous, tense, uncertain. But they were still looking forward to his treatment. Then, over lunch at the shop, Jenni sat with her mother, who said she was worried about her son. Jenni was, too. "I was like, 'You know what? Fuck it. I'm going to go check on my brother. He's in the trailer, they said he's cleaning up. He leaves for treatment in a couple days. I'm going out there.' ... I thought I would go back there and find him drunk and passed out, just a sloppy drunk mess."

Jenni said she went out to the trailer and knocked on the door, shouting for him that she wanted to borrow a tool from him. There was no answer. "So I ran inside and I grabbed a pry bar," she recalls. She forced open a window. "I had to crawl through the blinds. The blinds were closed. I just fell through. I fell onto the floor, rolled in."

She couldn't see William. But, she says, "the smell of my brother growing up, as a kid. He was the smell of a boy. He was like a little nerdy boy. The smell of him was a distinct smell. I could smell him."

Flashlight in hand, she found him in his bedroom, lying on his bed, already gone, she recounted.

Jenni ran back into the shop. She screamed. Her father ran out to the trailer. Her mother tried to follow him out there, but Jenni caught her. "I was like, 'You're not gonna see what I just saw. I won't let you.' And she tried to rip away from me, but I held her and I grabbed her, and I was like, 'You're not,' and I held onto her as hard as I could. And then I fell to the floor and she fell to the floor, and she sat on my lap. I was sitting on my knees. She just sat in my lap and I held her."

As Jenni says all this, she has tears falling from her eyes, but her voice is steady. She looks down and says simply and softly, "On March 8th, my brother took his life."

"We've been going through a pretty rough time as of late," Dave told me toward the end of our conversation. "But I think that's instilled in [Jenni] a very, very unique drive like 'I will not just do this, I will exceed in this'."

I told Kris that I am not looking for her to speak about that if she doesn't want to. But she said, "I think I talk about it because of the heartbreak that I felt for her. It did change her, you know?"

I asked her how, and Kris said, "I think it's made her really cherish life."

After her brother died, Jenni couldn't stay in her house alone. She went and lived with Alex for two weeks. Alex said it changed her "big time. When it first happened, she was in a delusional state, like 'This isn't real. My brother's still here.' She couldn't really accept it. She didn't know how to accept it."

Alex explained, "I was raised Catholic and [told her], 'Your brother is with you every day. He's in your heart. If you want to talk to him, talk to him. He's listening. He's walking around with you every day. He's watching over you.'" But once she came to accept what happened, Alex saw a positive change, particularly for her "appreciation for life."

"Going to Italy was probably the best thing for her because she came back so healed. She really did." Kris told me.

This was no vacation; it was a pilgrimage of sorts. Because while she spent most of her time backpacking, part of her time there was spent on a private VIP tour of Ferrari in Maranello, Italy. "I woke up at four o'clock in the morning and hopped on four different trains, and finally got to Maranello," she recalled.

The tour was arranged by a UK-based firm that Scuderia buys some of its parts from. They wanted to introduce her to the Ferrari reps as being from Scuderia Rampante, but Jenni is modest. "I was like, 'I'm no one. I'm just a girl who likes Ferraris.' " So she walked through the factory anonymously and quietly. "I just zipped my lips."

They made her put a sticker over the lens of her phone's camera so she wouldn't take pictures. She hardly minded. Rather, Jenni said, "It kind of made my heart beat. It just seemed like I was going places not everyone gets to go."

As she walked through the factory, Jenni said, "I was just in awe." She watched them build the cars she loves, that she has dedicated herself to. "Walking through [the factory], seeing how they build the Ferraris, seeing the assembly lines, it just made me feel like, I don't have a word for it," she told me.

And then, Jenni saw something she basically never sees in the U.S.—women working on Ferraris.

"I got to watch the women cutting the leather and making the dashboards and the doors and hand-sewing the parts," she said. "Gosh, I wish I had a word to describe how I felt, but I really don't know how to even describe that."

But it wasn't all delicate handiwork, Jenni told me. "It was not just women sewing and making the dashboards and cutting the leather. There were women on the assembly line with their toolboxes. It was just powerful to see those women in their Ferrari factory jumpsuits, working and wrenching... It was incredibly powerful."

Jenni recalled looked down at what she was wearing—her nice shoes and a skirt. "And here I am on the other side," she reflected, "usually greasy like them."

She was inspired to get home and get her hands in the grease again. "To see the engines being built, to see the assembly line, it simplified everything... I got it."

But her time at Ferrari wasn't over yet. Particularly because she did not introduce herself as the foreperson mechanic of Scuderia Rampante, she was surprised to receive a phone call shortly after she left the factory and returned to her hotel. Jenni said they "told her to come back so I could go inside and see the Ferrari Classiche."

This department is where Ferrari restores its own vintage automobiles—the rarest, most valuable sought-after ones. "I got to see what nobody gets to see, behind the closed doors, the vintage," Jenni remembered.

The trip was nothing short of life changing for her. "I set myself free," she told me.

She returned home a more driven, more decisive person. Her friend, Alex, picked her up from the airport. She looked at him and asked, "Will you be my boyfriend?"

She brought that drive back to Scuderia. And this renewed ambition has not gone unnoticed by her bosses. Dave Helms said, "She's got a lot of drive. She's got that eyes-wide-open, inquisitive, how-does-this-work [personality]. That's not a taskmaster knowledge. It's [more like] 'Let's get to the bottom of it,' which is something that's desperately lacking in the youth today. They want to be trained on how to replace a part; they don't want to know how it works, and that's an asset she has."

Maybe that's what makes a good mechanic—a desire to understand more, to do more. But how much more?

Jenni looked around at the 30,000-square foot space that houses millions of dollars worth of some of the most desirable and exotic cars in the world, and told me, "My dad won't retire. [But] my dad's gonna die one day... It's inevitable."

I asked her if she wants to take Scuderia Rampante over. She said she does, but that it's an intimidating thought. "I hope that it can just continue, and just let the tradition live on. By all means, I'll step up to the plate."

But she also told me, "I don't think I will ever get to where [my dad] is at. And he'll never be to where his mentor is at ever, even at my dad's age. He's always striving to get there. And I feel like I'll always strive to get to his level."

But on this point, her bosses don't agree.

"I feel she could be as good as him, if not better," Kris said. "She's young. She can do all the stuff that Dave doesn't even want to do on the newer cars," many of which are vastly more complex than the already finicky vehicles they made their name working on.

When I told Dave that Jenni doesn't think she can be as good as him, her mentor, he shook his head in a way that a parent does when they learn their child has done or said something foolish. "She could exceed what I know.... Her learning curve has been exponential," he told me. "She sees 10 years as a long time. I've been doing the Ferraris for better than 40 years, and I'm still learning. She's undervaluing her knowledge base."

Dave summed it up like this: "I think what you're seeing right now is just the iceberg breaching the surface."

In fact, he thinks the only person who doesn't recognize Jenni's potential for greatness is Jenni herself. "She just doesn't realize it," he said.

Perhaps she does. Before we bid each other a good night after her long day of wrenching on Ferraris, and her after painful retelling of her brother's death, we had one last beer and talked about cars—what kinds we like, what kinds we'd like to own, and of course, for her, how much pride and love she has for her career as the foreperson mechanic at one of the most revered Ferrari shops in the country.

Jenni smiled, and she looked at her hands and said, "This is what I'm doing. And I'm really good at it."

If you or someone you know is having suicidal thoughts, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-8255.

David Obuchowski is the host and writer of the new podcast, Tempest Powered by Jalopnik, which premieres on March 27. His reporting and essays have appeared in Jalopnik, The Awl, Longreads, SYFY, and other publications. His most recent fiction was published by the Kaaterskill Basin Literary Journal. David is also a musician with bands on Relapse Records, Old Flame Records, and Greenway Records.