'Women That Would Gladly Give Their Life': How The Paramilitary Women's Emergency Brigade Battled GM At The UAW's First Big Strike

This is a Jalopnik Classic post we are re-running in honor of Jalopnik's 20th Anniversary

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

"We knew—if we didn't win this time—the town would be a dead town," a member of the Women's Emergency Brigade said about her hometown of Flint, Mich. during the 1937 Sit-Down Strike on General Motors. "You know, there was just nothing to look forward to."

Many think of factory work, and therefore a strike in the automotive industry, as something primarily men would do. But it was the members of the Women's Emergency Brigade, a paramilitary group of women inside the United Auto Workers union, who proved to be the secret weapon in that group's triumph over General Motors. Their movement was born in 1937 amid one of the most contentious strikes in American history. Without these women facing down bullets and tear gas there may not have been a UAW, or labor movement, at all.

As the UAW's current strike with GM appears to be finally winding down after a month, it's worth revisiting how these women made history in the last century.

Men And Women Suffer Equally In The Shop

The United Auto Workers union was founded in Detroit on August 26, 1935, the same year President Franklin Roosevelt signed the Wagner Act, protecting people's right to organize. There had been halfhearted attempts to unionize autoworkers in the past, but this was the first organization dedicated to the industrial worker.

It was a necessary move at the time. Pre-union auto plants were truly hells on earth. GM plants were no exception.

Early GM shop workers describe conditions so brutal that their experiences read more like the treatment of feudal peasants than American employees in the 20th century. They had a job in the middle of the Great Depression, but that job did not guarantee steady pay. Most workers couldn't afford coats or sturdy boots. In the depths of the brutal Michigan winters, they were living without running hot water and shoving newspapers into their shoes and shirts to guard against the cold.

Moreover, the shop foreman's rule was absolute. He had total control over the fates of the workers below him. He could fire workers for no reason or force them to come work on his farm in off-hours. He could enter their homes and expect to be fed and entertained, or even worse.

"It was not unusual for a foreman to have your wife," Kenny Malone, who worked in Chevrolet Plant No. 6, told the Flint Journal in a 1987 special edition commemorating the 50th anniversary of the strike.

If workers spent 10 hours at the plant, but the line only ran for two or three due to breakdowns or delays, then the workers were only paid for those two hours but expected to stay for the whole shift. Some workers were paid by the piece—the part they made, the metal piece that fit over the dashboard, and so on.

Workers knew the "piece-work" system was a scam. It was meant to encourage efficiency and hard work, but if a worker did increase productivity enough to earn a little extra, the foreman would arbitrarily lower the pay of each piece so that there was no getting paid more—no matter how hard they worked.

Piece work eventually led to the dreaded "speed-ups" when workers on the assembly line were forced to work faster and faster. This unsurprisingly resulted in a huge increase in worker exhaustion and injuries. Fingers and limbs were the most common casualties of line work, but there were other dangers as well.

Workers would emerge covered in fine metal shavings from the constant sanding in the unventilated paint rooms or have their skin cracked wide open from the heat of the curing ovens. Injuries were severe, and if debilitating enough they would result in immediate dismissal, leaving families destitute. If anyone complained, they were often fired on the spot. After all, there were plenty of out-of-work men and women to replace them, willing to put life and limb on the line for any kind of pay.

One of the original General Motors plants, the Chevrolet Flint Complex or Plant No. 4, was called "Chevy in the Hole" by workers—a name it earned as an absolutely hellish place to work. Men would faint on the line from the summer heat. His fellow workers were expected to simply work around him until a foreman could drag the man off the line.

As bad as working in the shop was, the worst thing workers could imagine was being fired.

"You know it was the insecurity too, as much as anything else. The work was terrible. But that insecurity of never knowing if the boss is gonna take a dislike to you because you part your hair the wrong way and push you out," autoworker Thomas Klasey told a U-M Flint oral history project also around the strike's 50th anniversary. "And I think that was one of the worst things that they had to put up with, never knowing if they were gonna put bread in their kids' mouths from one week to the other."

When the Great Depression hit, men were laid off and women were hired in their place because women could be simply paid much less. The autoworker's $5 day (the figure that every American history textbook tells kids Henry Ford promised) was a dim dream for women on the line during the Great Depression. Women were paid 25 cents an hour for 10-hour shifts. And the work was dangerous and difficult.

"We figured it was a privilege to work in the shop," Nelly Besson, a lieutenant in the Emergency Brigade, said in the 1979 documentary With Babies And Banners. "There was no safety equipment of any kind. On the press I was on, the day girl lost two fingers. The bosses all said 'don't tell Nelly' but about 15 told me before I got through the gates.

"When I went in, there was a finger still laying on the press."

It's not just that women were as subject to the foreman's abuse as male workers; they expected it, as Besson remembered for the oral history project housed at the University of Michigan-Flint. She would eventually be fired from AC Spark Plug when someone reported her for attending a union meeting. But losing her job only strengthened her resolve.

The Emergency Brigade worked closely with the fledgling UAW. Yet the women's organization was founded not by an autoworker, but by a bourgeois socialist organizer from an old and storied Flint family.

Labor’s Joan Of Arc In The Company Town

Genora Johnson Dollinger, often called the Joan of Arc of the labor movement, was exposed to socialist ideals through her father-in-law who worked in a Buick factory. During her first battle with tuberculosis, Dollinger spent her time reading political literature. She made it her mission to educate her fellow Flint citizens about socialism, teaching classes and going door to door to distribute literature.

It was at a socialists' meeting in 1935 where she met Roy Reuther and Victor Reuther, brothers of future UAW president Walter P. Reuther and famous UAW organizers in their own right. Back then, the Socialist Party of America had many autoworker members, despite the danger to their livelihoods.

"They feared public opinion. They feared the [Flint] Journal. They feared their jobs. They knew," Dollinger said in oral archives. "General Motors controlled the paper. I mean, this is common knowledge. It's just absorbed in your skin as you grow up in a community such as this. They controlled the radio. They controlled your job. They controlled everything."

UAW organizers worked secretly, meeting with workers in the basements of their homes and keeping new members' names a closely guarded secret. GM's spies were everywhere, and anyone could lose their livelihoods for any reason.

Union officials, including the UAW's first president, suspected auto companies of employing members of the terrifying anti-union nationalist group called "The Black Legion," a violent organization that fashioned itself after the Ku Klux Klan.

In the early and mid-1930s, auto plants across the state were thought to have employed Black Legion members as union-breaking forces. Members would also infiltrate open union meetings, informing on workers with union leanings and beating organizers into submission.

Dollinger was a proud and fearless organizer, however. She could often be found making baloney sandwiches and coffee at the union's headquarters in downtown Flint's Pengelly Building or teaching classes on socialist thought or giving speeches to rally workers out of the "sound cars" cars with loudspeakers mounted to the roof. The women she organized were often wives, sisters, mothers or workers themselves, as women were barred from participating in the sit-in mainly due to social mores of the time. The wives of striking men didn't always trust the Women's Emergency Brigade, thanks to GM.

"General Motors sent them a letter and said that we were a bunch of 'entertainers' brought in here to entertain the men in the shop," Besson remembered. "So, then we started sending... some of the older women to talk to the wives because the wives were quite belligerent with us at times. They thought we were in there fooling around with their men."

Not all women joined the Emergency Brigade. They also had the option to join the Women's Auxiliary, which ran kitchens to get food to the men in the factory, printing presses to distribute signs and literature, first aid stations and childcare areas for the mothers who were on duty. They also walked a picket line while the men sat inside, stopping all work in the plant.

The Emergency Brigade generally included women without children who were willing and able to risk life and limb. After all, the 350-strong Women's Emergency Brigade would put themselves in the thick of the most dangerous and violent exchanges between strikers, police and GM goons. Founded during a bloody encounter between police and strikers, their purpose was to put themselves between the cops and the strikes, to shield the men with their lives if necessary.

"We weren't a tea-drinking society," Dollinger said.

Workers Sit Down To Stand Up For Themselves

The UAW knew if it were going to survive as an organization, it had to make a big impression and gain new members very quickly. So organizers set their sights on the heart of the largest industrial company in the world at that time: General Motors' factories in Flint, Michigan. These plants were important for another reason: Fisher No. 1 and No. 2 contained the only two sets of body dies that GM used to stamp out almost every one of its 1937 cars. They were crucial facilities.

But before the UAW could truly organize Flint, on December 30, 1936, several smaller strikes began at GM plants in other states. It was kicked off by UAW workers at a GM stamping plant in Cleveland to protest the arbitrary firing of a pair of brothers. Remember, while working conditions were terrible, losing your job was unimaginable, and job security was one of the main goals of the UAW.

The UAW then announced the strike would not end until the union had a national agreement with GM. When workers spotted GM moving the all-important body stamping equipment out of the plant, union members knew they had to act. They then announced Fisher No. 1 would also go on strike. And so began the longest sit-down strike in American history.

Between the first and the second shift workers at Fisher No. 1 had their workday interrupted but a group of fellow workers. "Everybody out! Everybody out!", the unionized workers cried. Some threw switches, turning off every machine in the plant. When non-union members refused to leave their post they were ushered out of the plant by union leaders who occupied the building.

Other GM plants in the city quickly followed suit. The sit-in strike had begun, and it would last 44 days.

There had been many minor scrapes between police and strikers, but things got fierce on January 11, 1937, when GM cut the heat to the factory in 16-degree weather. The company also tried to stop food from getting into the plant. When workers tried to leave to complain they were faced with fully-armed police officers as well as GM's private security force and anti-union workers trying to force their way in. Union members ran back inside the plant and then pelted police with bottles and bolts and eventually blasted them with fire hoses.

"Half of us didn't think we had a chance. Most of us didn't think we had a chance," striker Norman Bully recounted for the oral achieves. "But we could give 'em a hell of a rough time. And it was already goin'. What do you got to lose? You got to go for broke, you know. Once they shut it down and we were out, you gotta go for broke."

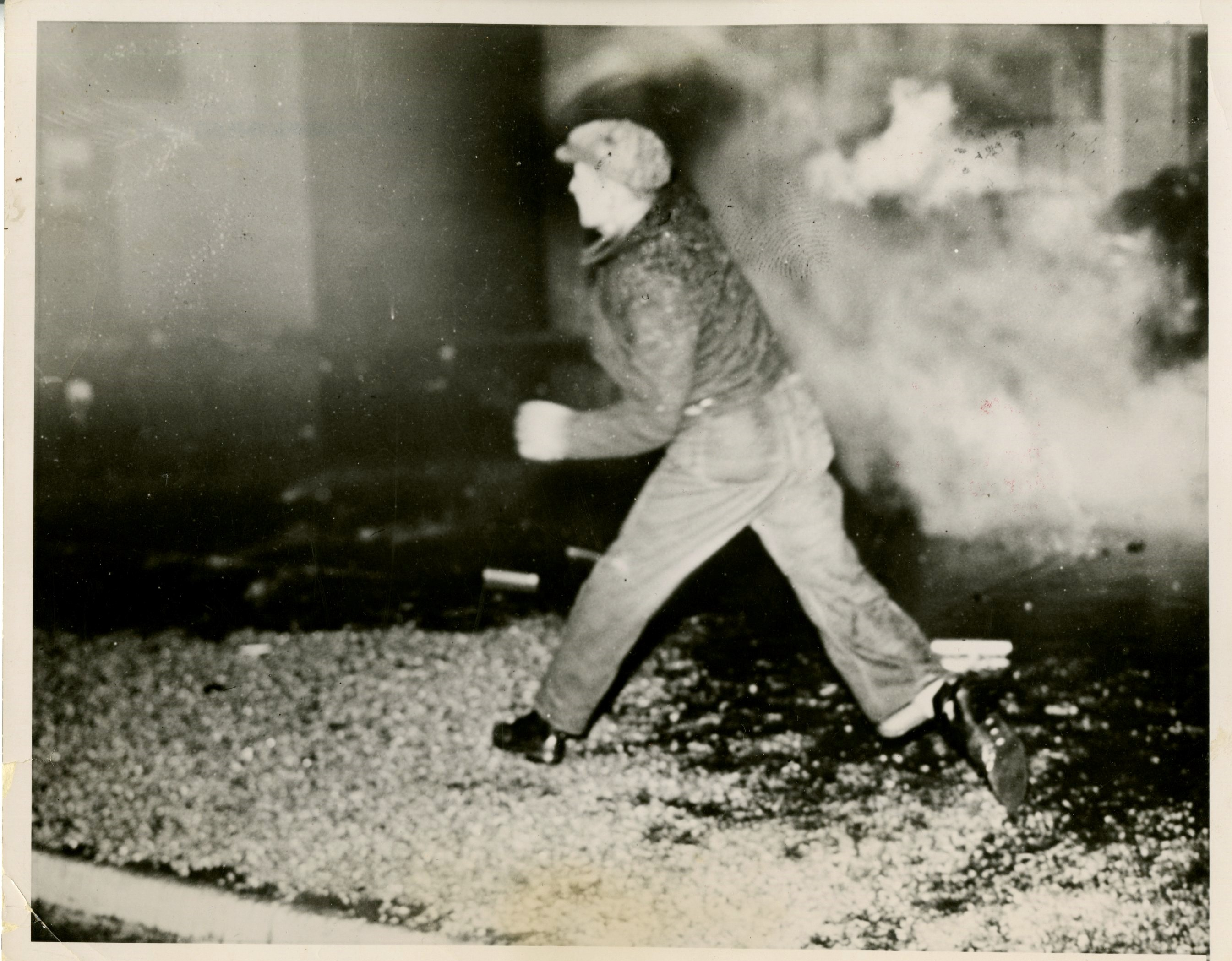

Teargas was shot into the crowd and through a window in the shuttered factory where 500 workers sat. Women who had come down to the plant to beg for their husbands to come home were caught in the crossfire. Shots were fired by police. The Battle of Bulls Run, a name meant to mock the police, had begun.

The melee would leave 28 officers and strikers injured before it was over. By the time Victor Reuther and Genora Dollinger showed up in a sound car, the scene at the plant was pure pandemonium.

After Reuther failed to rally the men and calm the escalating violence, Dollinger took the microphone, dodging buckshot with only moments left on the speaker's fading battery.

"I directed my remarks to the women on both sides of the barricades," Dollinger told author and historian Studs Turkel in the book Coming of Age. "I said the cops were shooting into the bellies of unarmed men and the mothers of children... I begged the women to break through those lines of cops and come down here and join with us.

"After that, other women came. The police didn't want to shoot them in the back. The women poured through and that ended the battle."

The courage of the women that night proved they were an asset to the cause.

While Gov. Frank Murphy called in the National Guard, he only did so to keep the peace, much to the chagrin of the city's fathers. Murphy was too nervous to authorize the use of force against strikers, especially with so many women in the mix.

That night, the idea for the Women's Emergency Brigade was born, though it would be officially founded on January 20, 1937, after Fisher Body No. 2 went on strike following the battle.

"We saw that there was such a need for women that would gladly give their life," Besson recounted in the oral histories. "Because that is practically what they asked us to do. We faced teargas and we faced rocks and we faced police and we faced National Guard and General Motors goons and everybody else."

They wore red berets and red armbands, which caused the Flint Journal to brand the women as communist agitators. In reality, the different colors denoted the different cites as the concept of the Women's Emergency Brigade spread to other locals. The Detroit women wore green and the Lansing women wore white.

The Women's Emergency Brigade would do anything and everything, from asking for food donations from businesses and local farmers to watching after sick children to responding to trouble spots in minutes to battling in the streets.

"I used a bobby sock and a bar of soap. But several of the women—you know, our coats at that time were longer—they had boards underneath their coats," Besson said. The Battle of Bulls Run wasn't the only place the Emergency Brigade faced down union breaking cops or GM goons. Besson remembered one particular exchange at Chevrolet Plant No. 9.

"[A striker] broke a window out. His face was all blood and he screamed 'they are gassing us, they are gassing us.' Just about that time the women turned and went into action," Besson said. The women used their billy clubs and soap-socks to break through the lower windows of the plant, allowing the tear gas inside to dissipate. "It was a beautiful sight."

Inside the plant, things were more orderly. Workers were given jobs to keep things humming along. Some gave lectures on socialist thought, and some held kangaroo courts, either sentencing rule breakers to extra scrubbing duty or even ejection from the plant for the true troublemakers. It was important to keep order within the plant. Damaging GM property was not the aim of the strike, and no one wanted to give Murphy a reason to send in his troops. And while the strikes faced down several encounters with police and GM's private goons, they never did go up against Michigan National Guardsmen in combat.

On February 1, GM was granted an injunction from a federal judge that deemed strikers were trespassing. Instead of leaving, thousands of armed strikers surrounded the Fisher body plants. Then the strike spread to the largest and oldest of GM plants: Chevrolet Plant No. 4, the Hole, where many of GM's engines were built.

Emergency Brigade members formed a human chain across the gates of the plant, refusing to break even under threats of violence from the police. As they stalled, other strikers flooded the plant. Taking GM's manufacturing heart hurt GM terribly.

In December, GM produced 50,000 cars. February saw only 125 cars built.

‘I Want To Be A Human Being’

Things quickly fell into place for the UAW after that. On February 11, GM signed a six-month contract with United Auto Workers. They won such basic rights as the right to speak to one another in the cafeteria.

GM agreed in that contract to a $25 million wage increase to workers and, most importantly, recognition of the union.

That led to a lot of growth. By 1937, UAW membership grew from 30,000 to 500,000 members. The union was now a force to be reckoned with. The strike also spread to other places. Within two weeks there were 87 active sit-in strikes in Detroit alone.

One of those strikes, the Yale & Towne Factory strike in Detroit, was a sit-down by mostly women workers. It took an army of 400 police officers using force and teargas to finally dislodge the striking women.

Yale & Towne closed up shop in Detroit rather than deal with a union. Women working at the Woolworth's in downtown Detroit also held a sit-down strike in 1937, with much more success.

Despite women-led strikes sparking in the cities in Michigan, the Women's Emergency Brigade was something rare and original in the labor movement. Dollinger acted to create the organization before the UAW had established a tradition of focusing on male workers and sidelining women.

"There was no established constitutional UAW with a contract... or anything," Dollinger said just before her death in the book Never Again Just A Woman. "There wasn't anything that they could do to us, because... [the union] hadn't yet organized."

It's one of the reasons Dollinger consciously made the decision to named her group the Women's Auxiliary and Emergency Brigade. Not a "Ladies" group, as other unions had relegated to women at the time.

"It was a radical change... To give women a right to participate in discussions with their husbands, with other union members, with other women, to express their views," Dollinger said.

Dollinger, Besson and their small force of 350 women transformed the way women saw themselves in the struggle for rights. They were an organization organized by women, for women who had just as much of an economic stake in the strike as the men. Dollinger's intention was to continue the Brigade and turn it into an educational force that could offer women relegated to the home a chance to become better informed and more thoughtful citizens.

But their flash of brilliance was not meant to last. Within a year of winning the strike, the Emergency Brigade disbanded. Dollinger ended up back in a tuberculous sanitarium and without her leadership and the constant threat of GM it fell apart. Even the proudly independent Emergency Brigade had to stick to the script of only existing to support the male strikers. Without relegating themselves to a support role, Dollinger said they "would have been talking to the wall."

In her essay, "Challenging 'Woman's Place'": Feminism, the Left, and Industrial Unionism in the 1930s," Sharon Hartman Strom wrote:

To argue that working-class women could somehow have mounted a viable feminist movement on their own is to engage in the worst sort of wishful thinking. To perceive as an individual woman that one's exploitation as a wife, a mother, a daughter, an employee, and a unionist were all connected was one thing; to struggle collectively on occasion against one or more of these conditions was another; to band together in the face of women's economic dependence on men and attack them all at once was impossible.

During and after the strike and for decades following it, their role was downplayed as mere cheerleaders for the courageous men—or worse, hysterical women who got in the way. In the first book written about the strike, The Many, and the Few by Henry Kraus, Kraus portrays the women who bravely faced police fire at the Battle of Bulls Run as "...hysterically castigating the police." Even internal UAW publications began to refocus women to "home" and "support" roles almost immediately.

"There is no greater duty to her family for the wife, the sister, and the mother of the worker than to become a member of the women's auxiliary" expounded a newsletter called Women in Auto in 1937. "In the future wherever you see a union engaged in a struggle, there will you see the women urging the union on to even greater achievements. The Union is no longer fighting alone. It has taken unto itself a wife—the AUXILIARY!"

But the women who wore the red berets were transformed by their involvement in the strike. They didn't see themselves as just the wives, mothers or sisters of men fighting for their breadwinner's rights. They were not a mere Auxiliary. They were, even for a moment, able to be soldiers in their own right.

Violette Baggett, a rank-and-file member of the Emergency Brigade, told the oral archives what she felt after her participation. "Just being a woman isn't enough anymore. I want to be a human being."

Special thanks to the University of Michigan-Flint archives, and especially to my sister, UM-Flint archivist Colleen Marquis, who assisted me with the research for this piece.