Trump's Trade War Threatens BMW's Biggest Factory In The World, But South Carolina Doesn't Seem To Mind

SPARTANBURG, SOUTH CAROLINA—Textiles used to dominate this part of South Carolina, which locals call the Upstate. But after the textile industry went overseas, BMW came in and built its biggest car factory in the world, bringing back prosperity in the process. But for more than a few voters and public officials in the area, many of whom could have their livelihood threatened by a trade war BMW has warned about, President Donald Trump's proposed tariffs aren't much of a concern—for now.

The Upstate, also known as the Upcountry, is the fastest-growing part of South Carolina, with over a million residents in the region and counting. Everywhere you look there is new construction, highways being expanded, businesses being erected. There are also traffic jams galore, a feature you don't expect in a region whose largest city, Greenville, contains around 68,000 residents.

Much of this region's boom can be traced to BMW, which opened the plant in 1994. The plant started as a producer of the then-E36 generation of 3 Series sedan, and today builds SUVs: the X3, X4, X5, X6 and the upcoming X7. It was the savior for a region that had seen 25,000 textile jobs disappear over the years.

"I was on the edge of the cliff and looking down," said David Britt, who's been on Spartanburg's County Council since 1991. "Everything was connected to the textile industry except one company, and that was Michelin."

BMW changed all that. "It just gave us so much confidence," Britt said. "It was a life-saving event."

Twenty four years later, as Britt says, "the proof is in the puddin'," with the region bustling and home to a critical plant for BMW, one that makes nearly all of the brand's SUVs sold worldwide. It is also the largest exporter of American-made cars, more so than even any U.S.-based car company. It employs more than 10,000 people, and tens of thousands more are employed in adjacent industries.

On paper, it makes sense that BMW is here, since the plant is next door to an airport, next door to an Interstate, and close to the Port of Charleston, from which the SUVs made at the plant are shipped to markets across the globe. South Carolina is also a right-to-work state, and the factory has proven to be almost impossible to unionize.

And while the region has thrived as a result, Trump's trade war has begun to imperil the plant's harmonious existence here for the first time.

Earlier this year, the president imposed 25 percent tariffs on aluminum and steel, which cost Ford alone $1 billion in profit. But the larger issue of tariffs on cars, specifically, has automakers even more worried, as Trump has threatened to slap 25 percent import taxes on those, too.

That might not affect BMW's bottom line in the U.S., but retaliatory tariffs overseas could hurt profits on the SUVs it ships to other countries from South Carolina. It would also give the company a strong incentive to build those SUVs elsewhere, namely somewhere like China. Indeed, BMW has already stopped exporting the X3 from Spartanburg to China, and it's started shifting SUV production more and more to that country and its South Africa plant.

"BMW has always made very clear it believes in free trade," Kenn Sparks, a BMW spokesman said in a statement. "For many years, BMW has considered the U.S. its second home. Our U.S. plant in South Carolina is currently the biggest BMW plant in the world, employing thousands of people, and for many years BMW has been the highest value exporter of vehicles from the U.S.

"But we have also said if the threatened tariffs take effect and undermine the competitiveness of BMW production and sales in the U.S., the result could be strongly reduced export volumes with negative effects on investments and jobs in the U.S."

And as the Columbus Dispatch noted earlier this year, the SUVs are hardly all-German and then assembled in South Carolina. They're made with parts from scores of suppliers across the U.S. and the world. All of them are threatened if the plant struggles.

For these reasons, BMW, like Volvo—which recently opened its own South Carolina plant—is staunchly pro-free trade, and has made no secret of the fact that if tariffs threaten the math of exporting SUVs from Spartanburg, its plans will be reconsidered.

This message, apparently, has not resonated with South Carolina's voters, perhaps because the 25 percent car tariff is still theoretical and, for now, the good times are still rolling.

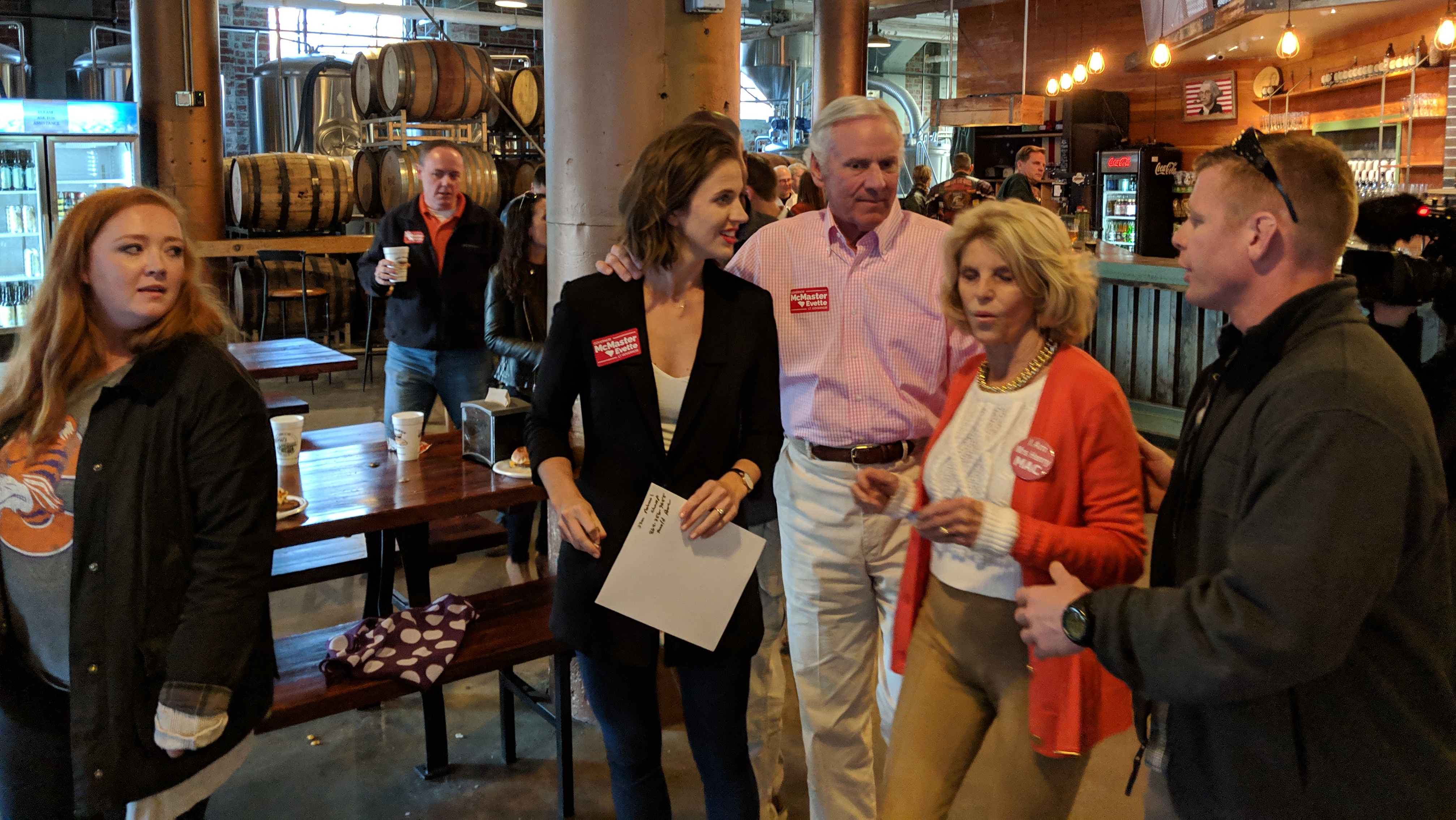

At a rally for the re-election campaign of Republican Gov. Henry McMaster I went to at a brewery on Saturday, the governor—one of Trump's earliest supporters—received applause for his support for Trump and the economic investment that has poured into his state. McMaster said that Trump is "probably one of the greatest presidents we'll ever have."

"We fell in love with him right away," McMaster added, recalling when Trump was trying to capture the Republican nomination. "They told me some time later, they said, 'Mr. Trump would like you to endorse him.' I said, 'Well, I like him a lot, who else has endorsed him around here?' They said, 'Nobody.' And I said, 'Well, I don't mean just in Columbia, I mean anywhere in the state.' They said, 'Nobody.' And I said, 'How about anywhere else?' And they said, 'Nobody.' And I said, 'I'm in!' And they said, 'You are?' And I said, 'I'll do it!'"

Afterward, I asked McMaster whether he still supported Trump given the tariffs and their potential impact on the BMW plant.

"All the negotiations about the tariffs are in progress," McMaster said. "Many have been discussed, few have actually been applied."

McMaster also argued that he was best positioned to protect his state from tariffs that would affect South Carolina.

"We want to be sure that any tariffs that are imposed help South Carolina and doesn't hurt South Carolina," he said. "We've been talking about tariffs with them and Volvo and everyone else ever since it came up. Constantly."

That latter argument I couldn't quite comprehend—McMaster wants to protect his state from the policies of a president he supports?—but that kind of thinking extended to McMaster's supporters as well.

"I think it might twinge just a little, but I think it's going to grow and level out," Ken Elrod, 52, a McMaster supporter and psychologist told me, before explaining what he liked about Trump. "I think he too is a good businessman. He's not the typical politician. I think he's a good businessman."

Look a little closer, and you'll see that this part of South Carolina is both prosperous and poor. BMW has been a boon, but go outside of Greenville and Spartanburg and signs of poverty emerge. The median income in Spartanburg County is $45,219, while in neighboring Greenville County it is $51,595, both numbers close to the statewide median income of $46,898. The textile industry died off much the same way steel and other industries did in America—automation and jobs being shipped overseas for cheaper labor, two issues that, ironically, the car industry contends with regularly as well.

On U.S. 29, for example, which connects Spartanburg and Greenville, the route is littered with things like businesses offering easy credit for those with less than optimal scores, a sure sign that, if nothing else, a strong market for such credit exists.

This part of the country isn't doing poorly, but like everywhere else, some people are doing better than others, with poverty rates here that hover around the national average of 12.3 percent. And so even with the current wave of economic prosperity, it has plenty of voters who won't directly benefit from a massive tax cut for the wealthy.

Nonetheless, Brandon Brown, the Democratic nominee for the House of Representatives seat that retiring Rep. Trey Gowdy, a Republican, currently occupies, is facing an uphill battle.

"They're afraid of the president," he told me. "I can remember seeing my friends being happy to get opportunities to work at BMW or Michelin. You don't toy with people's future."

Brown is targeting the BMW tariffs specifically as he runs. A section of his campaign website reads "BMW is under attack."

"We have to have someone standing up in Washington D.C. to tell the president he is wrong," Brown says in a video on his campaign Facebook page. "He is wrong with these tariffs that will hurt South Carolina jobs."

Brown's opponent is Republican William Timmons, a lawyer who has raised $1.2 million to Brown's paltry $49,480. Timmons has pretty much stopped campaigning in the final days of the election, confident in victory. He had do National Guard service the weekend before the election, but he found time on Monday to talk to me.

A 34-year-old who also owns a co-working space and yoga studio, Timmons is the kind of bright young conservative who acknowledges that Trump, in so many words, is useful for Republicans. He said he originally supported Marco Rubio in the Republican primaries before switching his allegiance to Trump, telling doubters that even if Trump was not a traditional conservative, the election was about the Supreme Court.

He also says that he supports what Trump is doing with the tariffs, arguing that the current terms—10 percent on cars imported to Europe from the U.S. and 2.5 percent vice versa—were inherently unfair, and he would accept some short-term pain to level them out.

"That's not free trade, that's not fair trade, and I'm not going to stand by and let it happen. So I support the president trying to actually get fair trade," Timmons said. "We don't got it now."

Timmons also said that the textile industry "cared more about the people" than BMW because they were U.S.-based. "Now our biggest corporations are not based here and we are, the term that's used is sharecroppers. We are sharecroppers," Timmons said, probably using an ill-advised metaphor given the region's history.

"Ultimately," he said, "the lion's share of their profits goes back to [Germany]," which Britt disputed and which to me seemed to discount all the prosperity I saw locally in Spartanburg as a result of BMW.

If McMaster waffled a bit on the question of tariffs, Timmons is unabashed in his support.

But Britt, the city council member and a conservative Republican himself, plainly called them a terrible idea.

"The United States has never won a trade war," Britt said, adding that he's urged the president to reconsider. "You don't do it with hammer, you do it with a handshake."

Britt also remembers when textiles left, and warned that could happen to the car industry should BMW begin to scale back. "The ripple effect is devastating," he said. "It's like dropping a meteor in a swimming pool."

For Brown, of course, the tariffs are the centerpiece of his campaign, even if he remained a flawed candidate, having been arrested for DUI in 2014 and engaged in a lawsuit with his employer after that, but his sins aren't of the unelectable kind.

But he's also optimistic for the Upstate's future. BMW has created a lot of new jobs, but a lot of those jobs have been filled by people moving in from out-of-state. People who might have different ideas about politics, he said.

"South Carolina has had an influx of positive-thinking people," he said. "The past... is slowly fading out. We've taken some baby steps."

Despite Brown making the BMW tariffs a specific platform in his campaign, the race is all but a foregone conclusion. The Cook Political Report doesn't rate it as competitive, and FiveThirtyEight forecasts that Timmons will get 65 percent of the vote, with Brown getting 31 percent and third-party candidate Guy Furay getting 3 percent. Brown says he'll campaign until the end, though.

"We have a very tight schedule," he said.

Halfway to Hell is Gizmodo Media's project covering the 2018 midterms; you can read coverage from across our network here and subscribe to our weekly newsletter roundup here.