The Indianapolis 500 Used To Be Part Of The Formula 1 Season

From 1950 to 1960, the Indy 500 awarded points toward F1's World Championship.

The Indianapolis 500 — America's premier racing event — used to be a Formula 1 race. Yes, you read that right: For 11 whole years, the Indy 500 was a points-paying race on the F1 calendar. As we approach the 106th running of the iconic race, which is running in tandem with a meteoric rise of American interest in F1, it's time to look back on the period in history where these two paths crossed.

The 1950 Formula 1 season was the fourth under FIA sanctioning, and the first that included the Indy 500. The thinking was, basically, that the Indy 500 was a big event worthy of being a Grand Prix. So, the FIA included the event on the F1 calendar through the 1960 season. It seemed like a pretty easy way to unite a predominately European fanbase with a predominately American one.

But the Indy 500 wasn't exactly a hit for the World Drivers' Championship. Indianapolis was a long way from continental Europe. The cars that competed at Indy were drastically different from those of F1, the sanctioning bodies were different, and the points-paying formats were totally unique. If you tried to run an F1 machine in a field of 32 Dallaras today, you'd have the same problems that drivers in the 1950s faced. There just wasn't a lot of similarity between the two series.

In the 11 years that the FIA included the 500 on F1's calendar, very few drivers and teams made any kind of effort at Indy. In 1952, Alberto Ascari joined the Ferrari team's Indy 500 effort. The Maranello organization sent four cars to the event, though Ascari only managed to qualify one of them, in 19th place. On the 25th lap, Ascari had worked his way up to ninth place before one of his Borrani wire wheels collapsed, sending him out of the race. In 1958, Juan Manuel Fangio failed to qualify for the 500.

Interestingly, though, F1 drivers grew a sudden interest in the Indy 500 almost immediately after the FIA dropped it from F1's calendar. In 1963, Colin Chapman fielded Team Lotus cars at Indianapolis, attracted in large part by the massive financial prizes on offer, biographer Gérard Crombac says. In the process, the fate of the Indy 500 was changed dramatically.

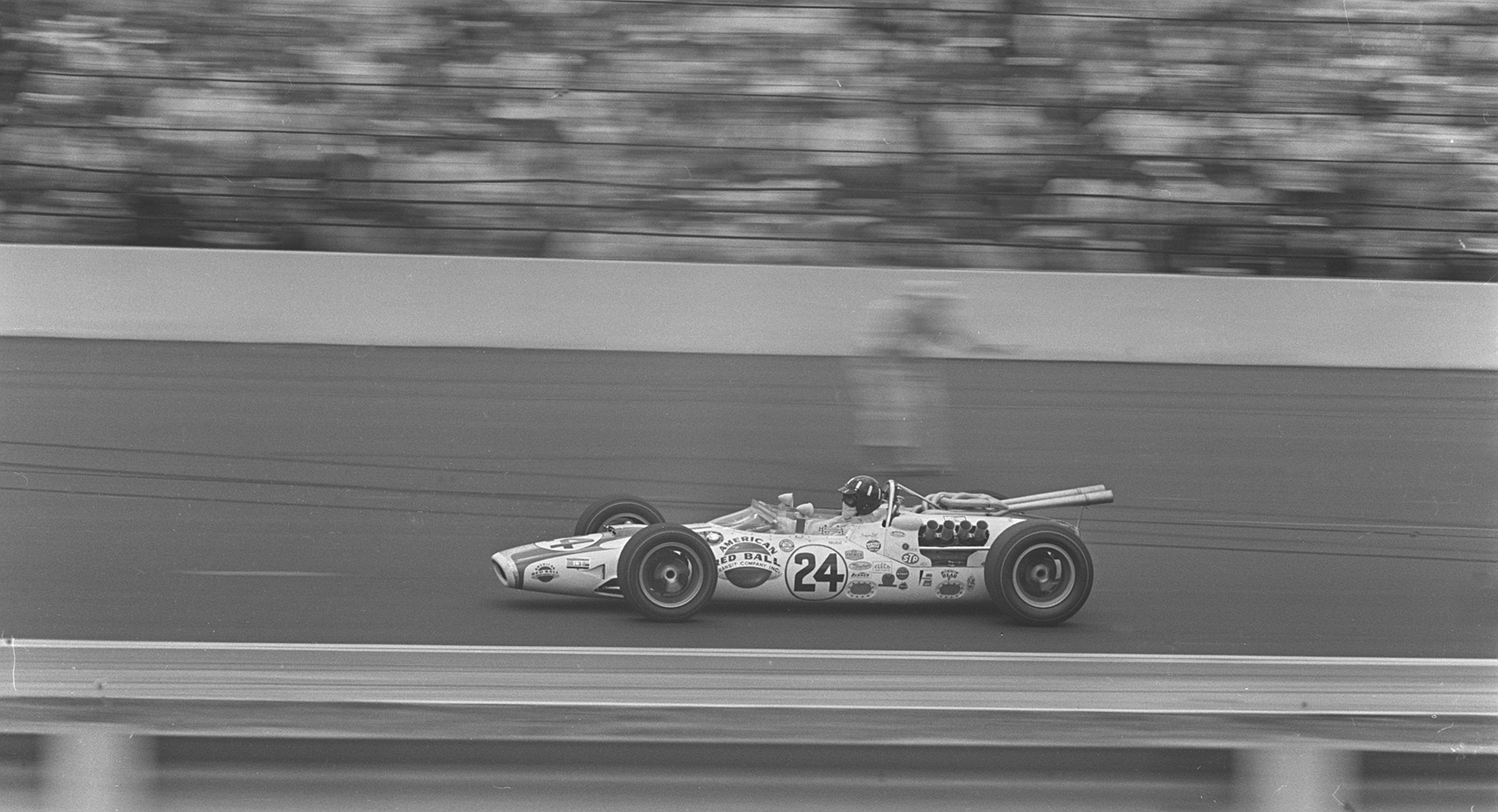

See, Chapman brought a mid-engined car that was smaller and lighter than the traditional front-engined Indy roadsters. That first year's performance made waves. With Jim Clark behind the wheel, the Lotus team finished second, behind Parnelli Jones and ahead of A. J. Foyt. The following year, Clark qualified on pole, and in 1965, he dominated the race. The next year, F1 ace Graham Hill took Indy 500 victory with a mid-engine Lotus-Ford.

The Lotus team totally redefined the scope of the Indy 500. By the end of the decade, heavy roadsters had completely disappeared from the race; teams needed to switch to more sophisticated, F1-style cars to stay competitive.

Mainly, F1's foray into the Indy 500 has left us with a legacy of silly stats. If you consider the years when the 500 was an F1 race, the United States has fielded 158 F1 drivers, second only to the United Kingdom's 164. By winning the 1950 Indy 500, Johnnie Parsons earned enough points to finish sixth in the F1 World Championship — despite never competing in Europe. Conversely, during the crossover era, most F1 Champions managed to secure victory despite never competing at Indy, one of just a handful of events on the year's racing calendar.

Plenty of F1 statisticians, though, tend to write off the F1/Indy crossover era, which is a shame. It was a time when F1 was trying to define itself as a championship. Ultimately, F1 came to style itself in stark contrast to the open-wheel racing happening in America — and, later, forced American open-wheel racing to modernize. We'll likely never see anything like that in motorsport again.