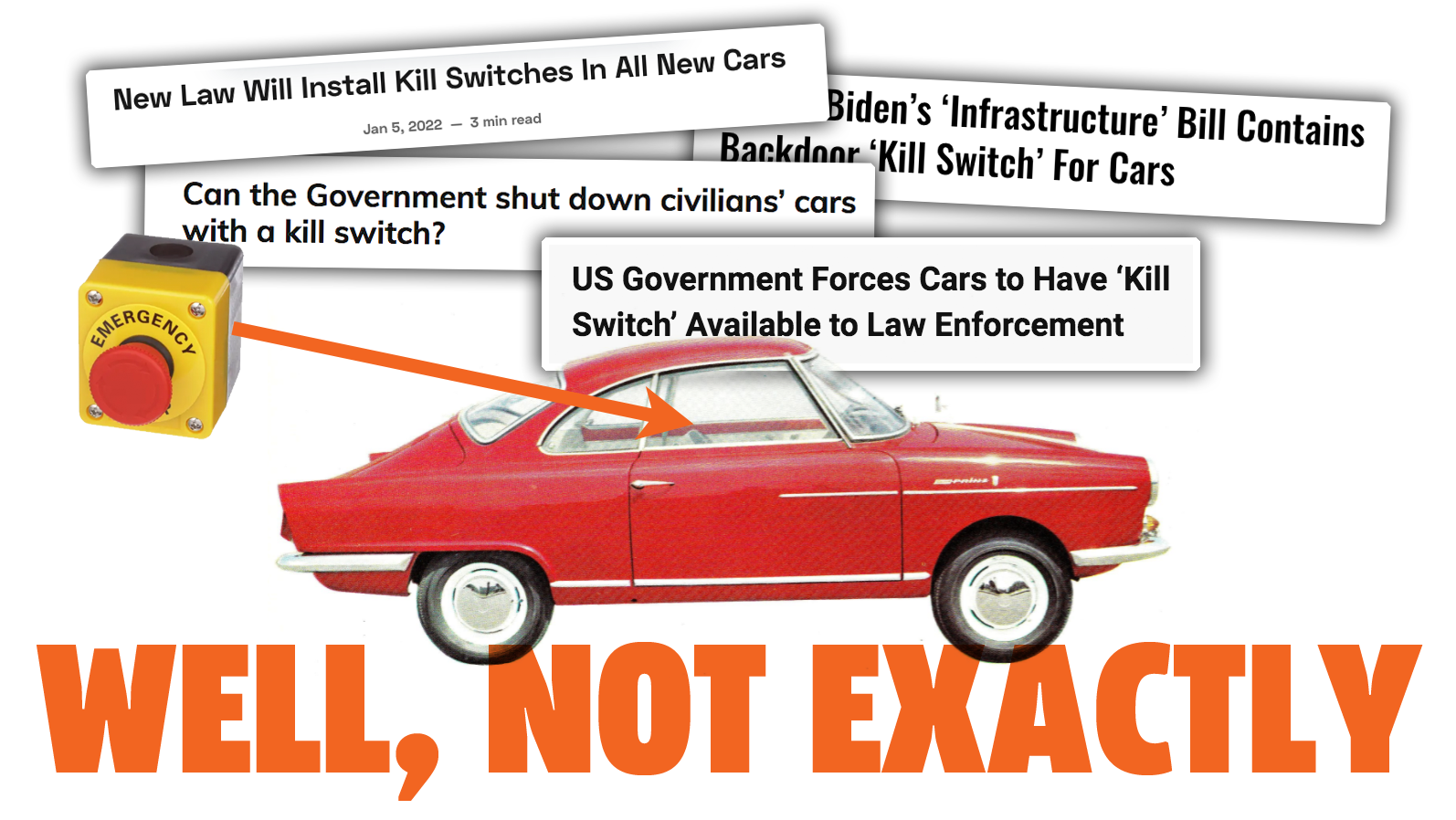

The Government Is Not Going To Force Your Car To Have A 'Kill Switch' That Police Can Use At Will

Most of the alarmism about this is misplaced, but there's still something there to be aware of

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Getting all worked up about things is a pretty good way to kill time if you lack other engaging pursuits. One exciting thing to get alarmed about is the possibility that the American government — already known to be kind of a dick at times — may be planning to force cars to have a kill switch, which is making a lot of people very upset at the idea. The only thing is that this isn't really happening, but, like most things we get alarmed about, there's at least a kernel of something worth keeping an eye on.

This all comes from a section of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, which became law in December of last year — you know, about a month ago.

We actually covered this new law already, and even the section in question, which is focused on providing anti-drunk driving tech for new cars.

The part of the law that has people worried is the mention of "advanced drunk and impaired driving prevention technology," which is defined in the bill like this:

(1)Advanced drunk and impaired driving prevention technology

The term advanced drunk and impaired driving prevention technology means a system that—

(A) can—

(i) passively monitor the performance of a driver of a motor vehicle to accurately identify whether that driver may be impaired; and

(ii) prevent or limit motor vehicle operation if an impairment is detected;

(B) can—

(i) passively and accurately detect whether the blood alcohol concentration of a driver of a motor vehicle is equal to or greater than the blood alcohol concentration described in section 163(a) of title 23, United States Code; and

(ii) prevent or limit motor vehicle operation if a blood alcohol concentration above the legal limit is detected; or

(C) is a combination of systems described in subparagraphs (A) and (B).

It's pretty clear that the goals of this section of the law are to reduce drunk driving fatalities and crashes via still-undetermined technological tools that somehow are able to "passively monitor the performance of a driver of a motor vehicle to accurately identify whether that driver may be impaired," and/or "passively and accurately detect whether the blood alcohol concentration of a driver of a motor vehicle is equal to or greater than the blood alcohol concentration described in section 163(a) of title 23, United States Code," and if either or both of these conditions are proven to be positive — if the car thinks you're drunk, then it may "prevent or limit motor vehicle operation."

So, they want cars to try to figure out if you're drunk by the way you're driving, detecting your blood alcohol level, or some combination of both, and then they want to do something to your car, if so.

This is not some "kill switch" that cops or congressional pages can activate by just pointing a big red button at your car, and you come rolling to a stop, at the mercy of being eminent domain'd by a congressperson hiding in the shrubs or dragged to jail by some cop.

Now, that's not to say this language doesn't bring up a crap-ton of issues, because it does, especially privacy issues. Privacy concerns have already been noted in detail by the ACLU, which has compiled a very cogent list of questions about the language in the law:

• How would it work? Video analytics technology (as we discussed in this report) has made great strides but continues to work poorly in many respects. In particular, a number of driver monitoring products are based on "emotion recognition" algorithms that are so problematic as to basically constitute snake oil. The visual detection of intoxication would seem to be an even harder problem.

• Would such a system falsely classify people with certain disabilities as being intoxicated?

• Such a system would require every car to have a built-in camera focused on the driver. Would that video be stored, or processed in real-time? Would that camera be available for other applications? If so, would the data all flow to the same place?

• Would the system check the driver when they start their car, or continuously monitor them while they're behind the wheel? The latter concept would involve the collection of far more data. It would also raise questions about how a car that is in motion — and potentially in the middle of merging onto a highway — could be safely disabled.

• Will the system minimize false negatives (allowing some people to drive even though they're drunk) or false positives (missing fewer drunk people but preventing more sober people from starting their cars)? Every system has errors, but depending on how sensitive you make it you can tilt the balance between false positives and false negatives.

All of these questions can sort of be encapsulated into the first four words in that quote: How would it work? The truth is we really do not yet have systems capable of performing the tasks required by the law.

Current camera-based driver monitoring systems used to determine if a driver is paying attention to the road while using driver-assist systems have been shown to be woefully inadequate, able to be fooled with novelty glasses you can order from WalMart, which doesn't bode well for a camera system determining if you're drunk.

I've known drunks who, were you to look at and talk to them, comport themselves no differently than sober. If you gave them a yo-yo, though, you'd soon be nursing their bloody lip, and if you were dumb enough to let them drive, you'd end up upside-down in an embankment while they sat there, dangling from their seat belt and quietly explaining to you why it's cool they think some Ewoks are sexy.

Cameras aren't going to work for people like that. Or, at the opposite extreme, if Radar Love comes on the radio while driving, a large segment of the population would probably flag any camera-based system, too, myself included.

There's no general-use car kill switch in the law, let's just be clear on that. But let's also be clear that what is in there is largely based on technology that is, at best, not mature, and while stopping drunk drivers is an extremely worthwhile goal, the implementation here does bring up a lot of privacy concerns.

Luckily, nothing here is likely to happen soon. Section 24220(c) of the law requires that the Secretary of Transportation issue comes up with a "final rule prescribing a Federal motor safety standard" no later than November 15, 2024, and there's an option for a three-year extension.

So, there's time to figure out if there's a way to implement an anti-drunk driving system without severely impairing the privacy rights of drivers and making something that isn't constantly sending false positives or is easily fooled.

This is a non-trivial problem, technologically, legally, and ethically. It's quite a can of worms to open, but nowhere in that can is a general-use "kill switch."

So, don't worry about that. Worry about everything else this entails.