The Devastating Loophole That Sticks Car Buyers With Interest Rates That Would Be Otherwise Illegal

On June 19, 2015, Bronx resident Carlos Guerrero-Roa went to an auto dealer in Brooklyn to purchase a 2005 Lexus RX that was being advertised online for $6,900. Guerrero-Roa left with the car that day, only after it was financed with a loan that, according to a lawsuit he later filed, carried an interest rate "well over" 25 percent—a threshold that New York state law deems a felony. But thanks to a loophole in the statute, Guerrero-Roa and countless others in New York end up with auto loans that have high, and possibly illegal, interest rates.

When Guerrero-Roa arrived at the dealer that day, his goal was to buy the Lexus with cash at the advertised price. But the dealer, CarsBuck, claimed that wasn't possible due to his low credit score—something that should never have been a factor on a cash purchase, the suit said. An employee told him the car could only be acquired "by way of a one-year financing plan," according to the complaint. In need of a vehicle to get around, Guerrero-Roa accepted the stipulation.

To complete the transaction, Guerrero-Roa signed an electronic pad, even though he wasn't able to view a computer monitor "displaying the document to which he was signing his name," according to the lawsuit. And he claims he wasn't given a copy of the agreement he signed. (The increased use of electronic contracts among auto dealers has been associated with auto loan fraud across the U.S., as Jalopnik reported in December.)

What Guerrero-Roa didn't realize was the transaction he'd signed off on actually required him to pay $18,998.40 for the car over 48 months—more than $12,000 over the initially advertised price. It wasn't until the company that financed the purchase, Westlake Financial Services, called him a few days later that Guerrero-Roa learned "he had borrowed over $18,000 to finance the purchase of the Vehicle," the lawsuit said.

In New York, charging interest above 16 percent is a violation of the state's civil usury law. Charging more than 25 percent is considered a felony.

But when Guerrero-Roa eventually obtained a copy of the contract for his loan, he confirmed the total amount was indeed nearly $19,000 and carried an interest rate that, his lawsuit alleges, violated New York's criminal usury law.

Westlake declined to comment. Steven Feinberg, an attorney for CarsBucks, pinned blame on Guerrero-Roa, saying the case had "nothing to do with usury and everything to do with buyer's remorse."

"Ultimately, all parties felt it was appropriate to unwind the deal," Feinberg said in an email. The case was eventually settled.

There's a wrinkle in New York's usury laws that still make transactions like Guerrero-Roa's possible, and it boils down to a basic question: What is a "loan"?

About 80 percent of all consumers obtain financing for a car through auto dealers, as opposed to their own banks or credit unions. Many likely believe what they're getting from the dealer is a loan, but legally, that's not always the case.

"To me, at the point that the legislature makes it a felony to lend more than that rate, why used car dealers should be able to do it is a mystery to me"

Typically, when a car buyer finances a purchase through a dealer, they sign what's called a retail installment sales contract, or RIC, a transaction in which the consumer agrees to make a fixed number of payments over time, plus interest, for the car. Think of it as a deferred payment plan.

In the industry, this is based on the "time-price doctrine," a principle that says dealers can have consumers pay an increased credit charge in exchange for receiving monthly installments over time, rather than the entire cash price up front.

If that sounds like a loan to you, you're on the right track. It's unquestionably similar, but New York law has a different set of provisions that govern what's permissible for RICs. Importantly, usury laws—and thus limits on interest rates—don't apply.

And that's the catch: New York state law allows auto dealers to set whatever finance charge they want for a RIC, so long as it's "agreed to by the retail seller and the buyer." In many cases, buyers don't even know what they are getting into.

Amid the increased attention toward subprime auto lending in recent years, little has been said about the policy decisions that let this industry thrive. When it comes to lending money to people with low credit, banks and auto dealers argue they have to charge high interest rates to account for the risk of a consumer failing to make their payment. Some states have laws on the books to cap how much risk is permissible.

(It's unclear how often prosecutions happen in for usury violations, nor how often dealers are targeted. But if a loan is determined to be in violation of civil usury laws, in some cases, it may be deemed illegal and void. Federal racketeering laws have also been deployed in the past to criminally prosecute individuals accused of usury violations.)

But policy changes and court decisions over the last quarter-century have effectively neutered state usury laws. And attempts to argue in court that usury limits should be applied with more force on auto loans have been, for the most part, unsuccessful.

That hasn't stopped regulators and lawmakers in states like New York from considering further steps to bolster usury provisions. In recent years, New York lawmakers have toyed with making significant changes but to little avail, leaving car buyers like Guerrero-Roa exposed to auto dealers who set interest rates as they please.

"To me, at the point that the legislature makes it a felony to lend more than that rate, why used car dealers should be able to do it is a mystery to me," Daniel Schlanger, Guerrero-Roa's attorney, told Jalopnik.

The problem, attorneys and consumer advocates say, is that car dealer operations are so intertwined with financial institutions that would otherwise be subject to the state's usury law. The involvement, they say, of financial institutions along every step of the way is fundamental for most car sales.

Dealers are in need of cash to pay off the line of credit they tapped to put cars on their lot in the first place. So they take the RIC and sell it to a bank or finance institutions—institutions that, oftentimes, pre-approve the financing terms before a car sale is ever completed and the contract is signed. In many cases, the dealer provides documentation to a car buyer that has a financial institution's logo stamped at the top.

As a result, the financial institution quickly ends up with the rights to a RIC they're legally entitled to collect principal and interest payments on.

There's a term for a RIC in the industry: an "indirect" loan. New York law says it would be a felony for a bank to directly provide a loan with a 25 percent interest rate, but if it purchases a RIC from a car dealer with a rate that high, it's perfectly fine. Call it what it really is, consumer advocates say: a loan.

"Everybody—even dealers—refers to these as loans," said John Van Alst, an attorney with the National Consumer Law Center and expert in auto finance issues. But buyers are the ones getting screwed as a result.

In effect, the unfettered access for financial institutions to buy auto RICs allows them to circumvent the usury cap and make money on loans they otherwise couldn't offer to consumers.

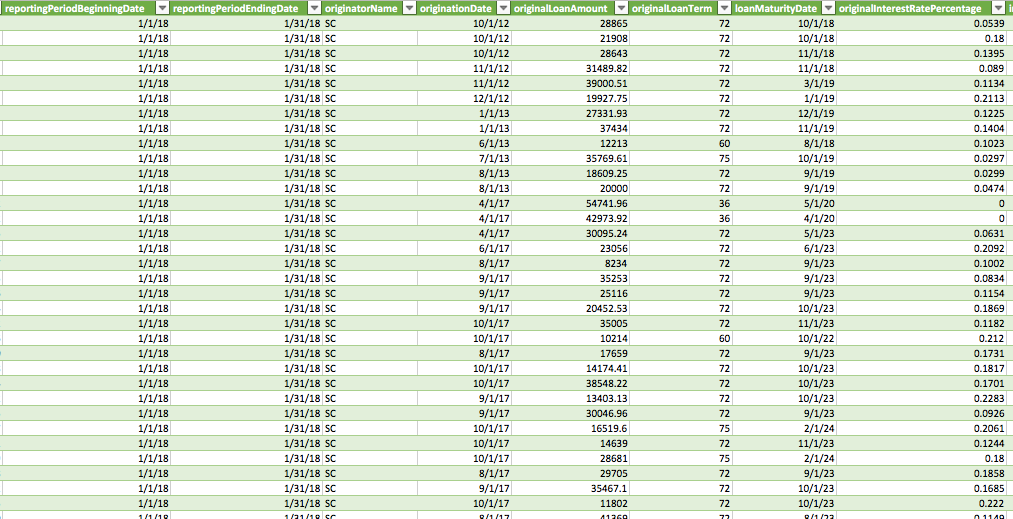

Detailed auto loan data isn't readily available to the public, as is the case with mortgages, but some federal records offer illuminating insight.

Take Santander Consumer USA, a major subprime auto lender.

Last month, Santander offered Wall Street investors $938 million in securities full of RICs for new and used cars and light-duty trucks. With the guarantee of being able to repossess vehicles if consumers don't make their payments, it was an easy sell.

But of the roughly 3,000 indirect loans in the package that were originated in New York, 57 percent had interest rates that exceeded the state's civil usury cap, according to records filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission. Fifteen loans exceeded the criminal usury cap of 25 percent.

Santander declined to comment. The company previously argued in court filings that the law's design allows it to accept these indirect loans, even if they contain interest rates that appear usurious. In a 2016 bankruptcy court filing, the company said it buys installment contracts from auto dealers so they can "sell vehicles to consumers who have credit histories that prevent them from qualifying for traditional financing."

"We do not believe that these types of contracts should be exempted from the usury cap. We think the interest rates are so, so high."

Some New York officials have tried to rein the lending model in. A few years back, state lawmakers proposed applying the usury caps to all RICs, but the recommendation appears to have never been taken up. That hasn't stopped attorneys or officials in New York City from trying to bolster the state's usury law when it comes to auto lending.

In a report last year, for example, New York City's Department of Consumer Affairs recommended applying stronger interest rate caps for RICs "to reduce unscrupulous and overzealous used car dealer behavior."

Lorelei Salas, commissioner of this department, said she has taken legal action in recent years against auto dealers who've made shoddy transactions with subprime consumers. She said her office, which regulates several hundred car dealers in the city, believes applying the usury cap to all RICs could "really bring changes to this industry and protect consumers."

"We do not believe that these types of contracts should be exempted from the usury cap," Salas told Jalopnik. "We think the interest rates are so, so high."

Salas' office laid out the crux of the issue in a November lawsuit filed against a number of financial financial institutions allegedly involved in "predatory" auto lending, including Westlake, the company that provided the auto loan to Guerrero-Roa. It was later settled for $300,000.

"Although RICs are agreements between consumers and Dealers, consumers have very little actual negotiating power," the filing said. The RIC, the filing continued, is "effectively negotiated" between dealers and the finance company, which obtains the right to principal and interest payments from the consumer shortly after the agreement is signed.

By playing such a significant role in the overall sales transaction, the arrangement is ultimately lucrative for financial institutions.

"Finance companies profit handsomely from this arrangement, given the nearly criminal, often fraudulently obtained annual percentage rates with which dealers and finance companies saddle consumers," according to the filing.

One of those consumers was Marion Whittle. In February 2016, Whittle drove 80 miles from Connecticut to Brooklyn to look at a 2007 Volvo XC90 being offered by a dealer for $6,900. Upon arrival, a salesperson for the dealer, D&A Guaranteed Auto Sales, told her the price was nearly double, at $12,900.

According to the court filing from Salas' office, Whittle was convinced to make a $2,200 down payment, before D&A's finance manager "rushed her through the paperwork," and said if she didn't sign the papers fast, the transaction couldn't be processed before the bank closed. She was told her down payment would be lost, the filing says.

The dealer declined to give Whittle a copy of her RIC, according to the filing, and said the finance company it was being sold to would provide one. Weeks later, when Whittle finally received a record of the agreement, she discovered that D&A increased the price an additional $1,650 to $14,550.

What's more, the agreement stipulated a 23.99 percent APR—barely shy of the criminal usury cap in New York—"bringing the total cost of the Volvo to $26,019.60," the court filing said. The terms of her 60-month contract meant she'd be required to make a $388.60 payment on the car every month until March 2021.

Had New York's usury law applied to Whittle's retail installment sales contract, the auto dealer—and, in turn, the finance company—could only charge a rate of up to 16 percent, saving her roughly $4,000 in interest payments.

"If, by some miracle, she does not default on the RIC," the filing says, "her car payments will likely outlive her car."

Over the last several decades, policy changes and court decisions aimed at deregulation have effectively rendered usury laws moot when it comes to consumer credit.

A groundswell of change occurred following a 1978 Supreme Court decision in the case of Marquette v. First Omaha, which found that a national bank is only subject to the usury cap set by the state where it's based—not where the borrower resides. It created an opportunity for states looking to attract financial institutions; for instance, South Dakota, which had no usury law, soon found itself home to several credit card issuers.

"This federal preemption on states for [setting usury policy] really undercut the ability of states to set their interest rates," Van Alst, the attorney from the National Consumer Law Center, said. Some states followed suit and also eliminated caps on finance charges for RICs.

That's what New York did in 1980. Under the New York Motor Vehicle Retail Installment Sales Act, the state opened the floodgate for dealers to set whatever rate they please.

"As a result, dealers regularly charge consumers an APR of 24 percent—just one percent below New York's criminal usury interest rate," the court filing from Salas' office says. State law allows some institutions obtain licenses so they can set interest rates above the 16 percent civil cap, in limited circumstances. That's why attorneys say it's so common to find auto loans with charges that stop just shy of the criminal usury rate.

Some dealers apparently have no problem exceeding New York's criminal usury rate, however. That was evident based on SEC records reviewed by Jalopnik.

"There's the lender behind the scenes who's pulling all the strings. They're doing the credit check, they're deciding whether or not the person's going to get the loan."

The records cover 3,066 car purchases in New York that were financed by indirect loans made by Santander. Of that amount, 1,742—57 percent—exceeded New York's civil usury cap of 16 percent. Nearly 125 purchases had a rate of 24.99 percent, while 16 loans had rates set at 25 percent and above, a possible crime had they been made directly by Santander.

Attorneys who regularly handle cases involving subprime auto loans were floored to learn that Santander financed seemingly usurious transactions.

Shanna Tallarico, supervising attorney for the New York Legal Assistance Group, Supervising Attorney, said that, in her experience, it's clear that a financial institution is involved at every step of an auto sale.

"There's not really this discussion between the buyer and the seller," she said. "There's the lender behind the scenes who's pulling all the strings. They're doing the credit check, they're deciding whether or not the person's going to get the loan."

The SEC records show how easy it is for a "loan" to be conflated with a retail installment sales contract. One section describes the "original interest rate percentage" of each loan—not the "finance charge" that's, in theory, prescribed to a RIC. The records show loans and RICs are listed interchangeably.

Since the financial institution is so integral to the process, Tallarico said, the financing should be treated as a loan under state law, not a retail installment sales contract, and so auto dealers shouldn't be able to charge unreasonably high rates.

"They're getting away with it because the law is allowing them to get away with it," she said.

In recent years, subprime auto loans have received extra scrutiny by consumer advocates and state and federal regulators. That's because, following the mortgage crisis a decade ago, subprime auto lending gained traction across the U.S., helping boost car sales to record numbers for the industry.

That trend has had an unfortunate side effect. The most recent available records show Americans now owe a record $1.1 trillion in car loans, while 6.3 million people are 90 days or more late on their loan payments. People are borrowing record amounts to pay for a car, with loans that take on average 72 months to pay off, a record that has troubling consequences. Exceedingly high interest rates are commonly associated with repossessions.

One subprime auto lender annually expects to repossess 35 percent of the cars it finances. (Even the biggest Buy Here Pay Here dealers—more commonly associated with abusive lending practices—have lower repossession rates, closer to 20 percent, according to a report from New York state lawmakers.)

"The problem is the high income inequality that puts people in these situations where it's clearly sensible for them to borrow at high interest rates because that's the only way they could do something they really need to do, like get a car."

"Lenders make money whether or not the borrower can repay the loan," said Rebecca Borne, senior policy counsel with the Center for Responsible Lending. "They can repossess the car, the loan values are often twice as large as the value of the car. Repossession can be a quick and relatively easy process for the lender."

There's no exact figure on how many New York consumers obtained an indirect auto loan that could violate the state's usury law, but it's clear that car buyers in the state are susceptible to higher costs due to the lack of a maximum interest rate cap for auto dealers.

A 2014 report by the National Independent Automobile Dealers Association found that New Yorkers made $45.5 billion in automobile purchases that year, and a vast majority of those sales were made through dealers who provided car buyers financing from an indirect lender. The association estimated that 16 percent of new loans made that year for cars in New York went to subprime consumers, which tracks with the nationwide average.

That means nearly one out of every five car buyers in the state could be subjected to an auto dealer that offers financing at seemingly usurious interest rates. Some may not even realize it.

That's what happened recently to Justin Robinson, a 36-year-old Queens resident who's originally from Haiti and currently works as a home aid worker for Medicaid patients.

In November, Robinson visited Bayside Chrysler, an auto dealer in Queens, to purchase a car, but wound up with a nearly $50,000 loan for a Jeep he couldn't afford. Robinson has limited English proficiency, explained Stan Weinblatt, an 85-year-old Medicaid patient that Robinson looks after. Weinblatt conveyed a summary of Robinson's story in a phone interview this month with Jalopnik.

"They kept him there for eight hours," Weinblatt said. "They wouldn't let him out. They just kept badgering him and badgering him. The next day he told me what he had done. I said, 'A new car? How could you afford a new car?' He seemed so happy about having it."

Robinson didn't seem to understand the terms of what happened. As it turned out, the dealer had allegedly falsified his income on documents, according to Robinson's attorney; this provided clearance to pair him with a more expensive car.

Robinson had purchased a 2017 Jeep Compass with what was not a loan, but an RIC that carried an interest rate of 16.52 percent. His monthly payment would've been $688.04, with total payments coming out to $49,538.88. (A request seeking comment from a Bayside rep wasn't returned.)

"He was very shocked and upset," Weinblatt said. "My wife and I looked at the contract, and I don't think he really understood it. I told him, 'Do you realize what this is expecting you to do?'"

Within a month, unable to pay the bill, Robinson convinced the dealer to take the car back. But a letter recently sent to him by the company that financed the deal—Santander, again—suggested it plans to hold him liable for the terms of the contract, said attorney Tallarico, who's representing Robinson.

Weinblatt said that would be devastating, if true.

"He's the sweetest guy in the world," Weinblatt said. "We consider him like family. He's so good to us. I hate for him to go through with this."

So what could happen if New York's lawmakers applied the usury cap to every auto sale that's consummated by a RIC? That depends on who you ask.

A common argument touted by the finance industry is that a cap could prevent subprime consumers from being able to obtain a loan for a car. (Representatives for two of the biggest lobby groups that represent auto dealers didn't respond to requests for comments.)

"You'll tell people you can't borrow the money, and can't have a car," said Ronald Mann, law professor at the Columbia Law School. There's a more obvious issue, he added.

"The problem is the high income inequality that puts people in these situations where it's clearly sensible for them to borrow at high interest rates because that's the only way they could do something they really need to do," Mann said, "like get a car."

The basic principle of usury law has been around for millennia. If creditors can set terms of a loan with no limits, "desperately poor people will end up in transactions that are crushing and awful for them," said Schlanger, the attorney who represented Guerrero-Roa.

"And so the general argument against all usury law is that it's hurting poor people because you're not letting them into [high interest loans], I think is extremely weak," he said.

"If you can't make money lending at 25 percent a year... I don't have much sympathy," Schlanger added.

A similar argument was made by a judge in a 2010 case involving Tabatha Black, a Staten Island resident who'd purchased a car from a Ford dealer. The RIC signed by Black and Ford Motor Credit Company stipulated an annual percentage rate of 24 percent, according to an opinion issued in the case.

Ford argued the rate was legal because it was agreed upon by Black and the dealer. Philip Straniere, the Staten Island civil court judge overseeing the case, found the automaker's argument unpersuasive.

"If you can't make money lending at 25 percent a year ... I don't have much sympathy."

"Clearly, this cannot be the law," Straniere wrote. "At some point a court must be able to step in and find, even though there exists a written agreement, the terms are so unconscionable that they are beyond being just unfair, they are unenforceable."

The judge ruled Black's agreement with Ford was indeed subject to the state's maximum interest rate caps and deemed it usurious. It appears to be the only known case in New York where a judge ruled the usury cap applied to a retail installment contracted signed for the purchase of a car.

"If the interest rate was 16 percent, maybe this woman never goes into default. Maybe it's a manageable number for her," Straniere, who recently retired from the bench, told Jalopnik. "How much money do [dealers and finance companies] have to make?"

A 2015 lawsuit brought against Santander by a New York resident tried to argue that finance companies illegally circumvent the state's usury law because of their integral relationship with auto dealers and car sales. The case, filed by Franklyn Garcia, involved a $26,000 loan for a 2011 Dodge Durango that carried an interest rate of 23.67 percent, and it cited the Black case to bolster its argument.

The judge in Garcia's case ultimately found the Black ruling wasn't a "persuasive authority" and dismissed the complaint. But the judge's opinion reads as if they might've ruled otherwise—if New York's law didn't effectively exempt auto dealers from the state's usury limit.

The current situation leaves low-income people in a tight spot. It's financially wiser to purchase a car outright with cash, or obtain financing from a bank or credit union to then shop around for the best deal. But the reality is that many are simply unable to scrounge together the savings for a reliable car, leaving them with used auto dealers and subprime lenders as a last resort.

Advocates say an interest rate cap has been shown to work, and it's clear there's an appetite to implement some sort of limit. In October 2016, a federal law went into effect that created a maximum rate of 36 percent for military service members that covered, among other things, retail installment agreements. A federal law introduced last fall that's co-sponsored by Democratic Senator Dick Durbin would apply a 36 percent cap to "all consumer credit transactions," including car loans.

"Capping interest rates and fees for consumers will help protect working families from these predatory lending practices—it's the right thing to do," Durbin, who didn't return a request for comment, said in a statement at the time.

New York City is also taking action. A few years back, the city's consumer affairs department launched an initiative to find lenders who would explicitly agree to provide auto loans that didn't violate the civil usury cap, and contained terms that were easy to understand for consumers.

And Salas, the department's commissioner, is gearing up to enforce new local laws that will require dealerships to disclose the lowest rate offered by lenders. "In the past, there was nothing requiring them to do that," Salas said. "The dealer would just decide what loan offer to make, and the consumer didn't really know what offers were available to them."

To date, she said, her office has held nearly 90 events with the community on auto lending. "Consumers should be armed with the right information before they walk into the dealership, she said.

But without action from state lawmakers, the impact her office can have is limited, Salas said. A maximum interest rate cap that's applied to all car sale transactions is a smart idea, she said, but it's not something she can effectively put into action.

"It's not something that we in New York City have the ability to change," Salas said. "It's something that our state government leaders need to look into."