The BMW Z1 Was The Car Of A Future We Didn't Deserve

The 1980s were good years for BMW. This was the yuppie decade, when E30s ruled and M cars blossomed. This was even when the company finally got its V12 engine project off the ground, having sat in development hell since at least the early 1970s. The bar was getting raised, and in 1987, with the BMW Z1, the company really went for it.

BMW showed off in 1987 the "Z1 High Tech Roadster." Though the idea of it was retro (BMW hadn't made a dedicated roadster since the 507 of the Blue Suede Shoes Elvis era), it was meant to be forward-looking. Z was for Zukunft, future.

Indeed the car was futuristic. The body was of advanced composites and, most notably, it had doors that rolled down into the high sills of the chassis.

The basic engineering of the car was pretty simple. It was sort of like a super version of the E30. The front suspension was the same, and the rear was made into a multi-link called a "Z Axle," which was sort of what the next 3 Series, the E36, got.

The Z1 engine was just what you'd get in an E30, the 2.5-liter M20 straight six, good for 168 horsepower. Weight was around 2,800 pounds. Nothing bad, nothing extraordinary.

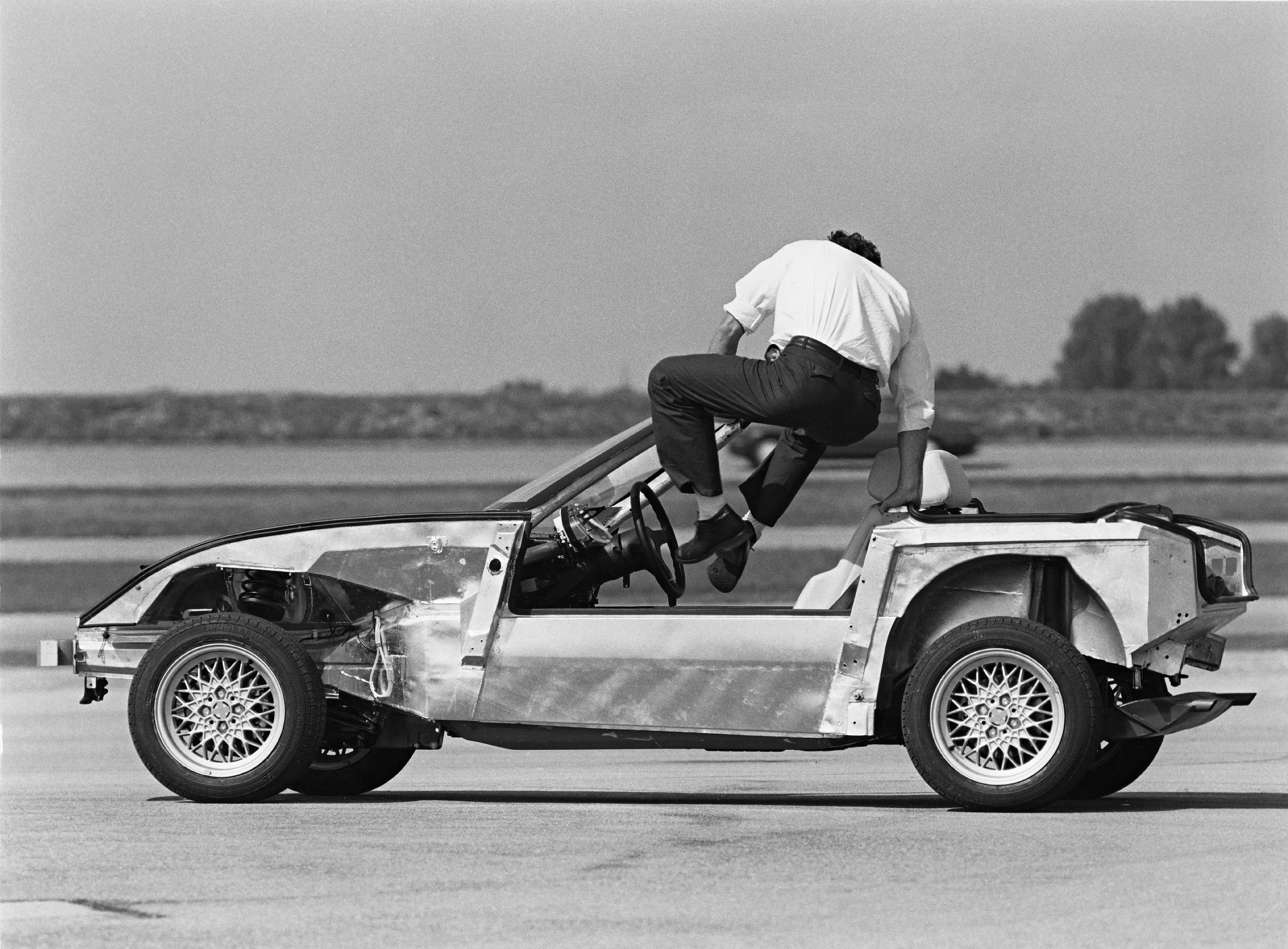

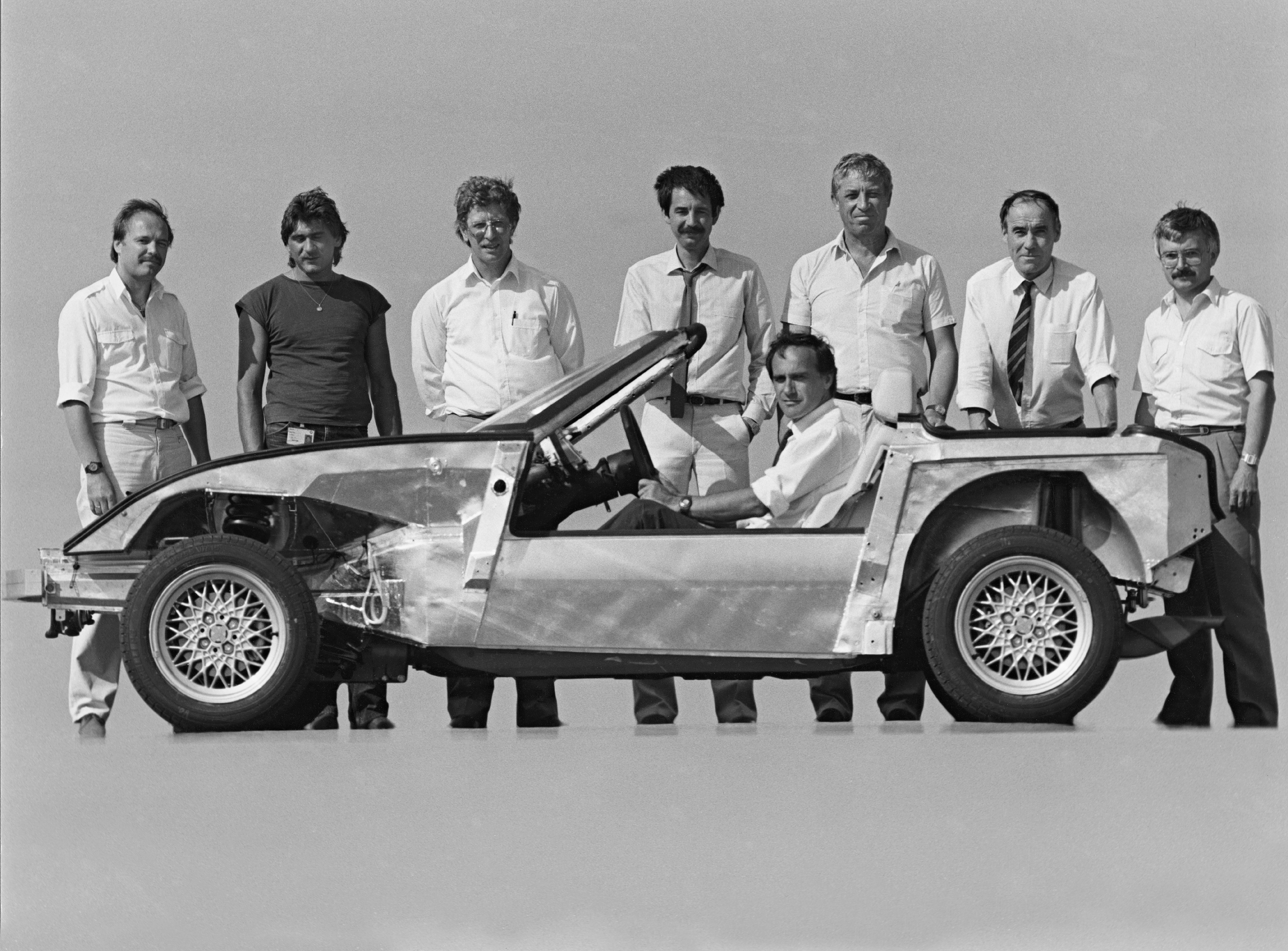

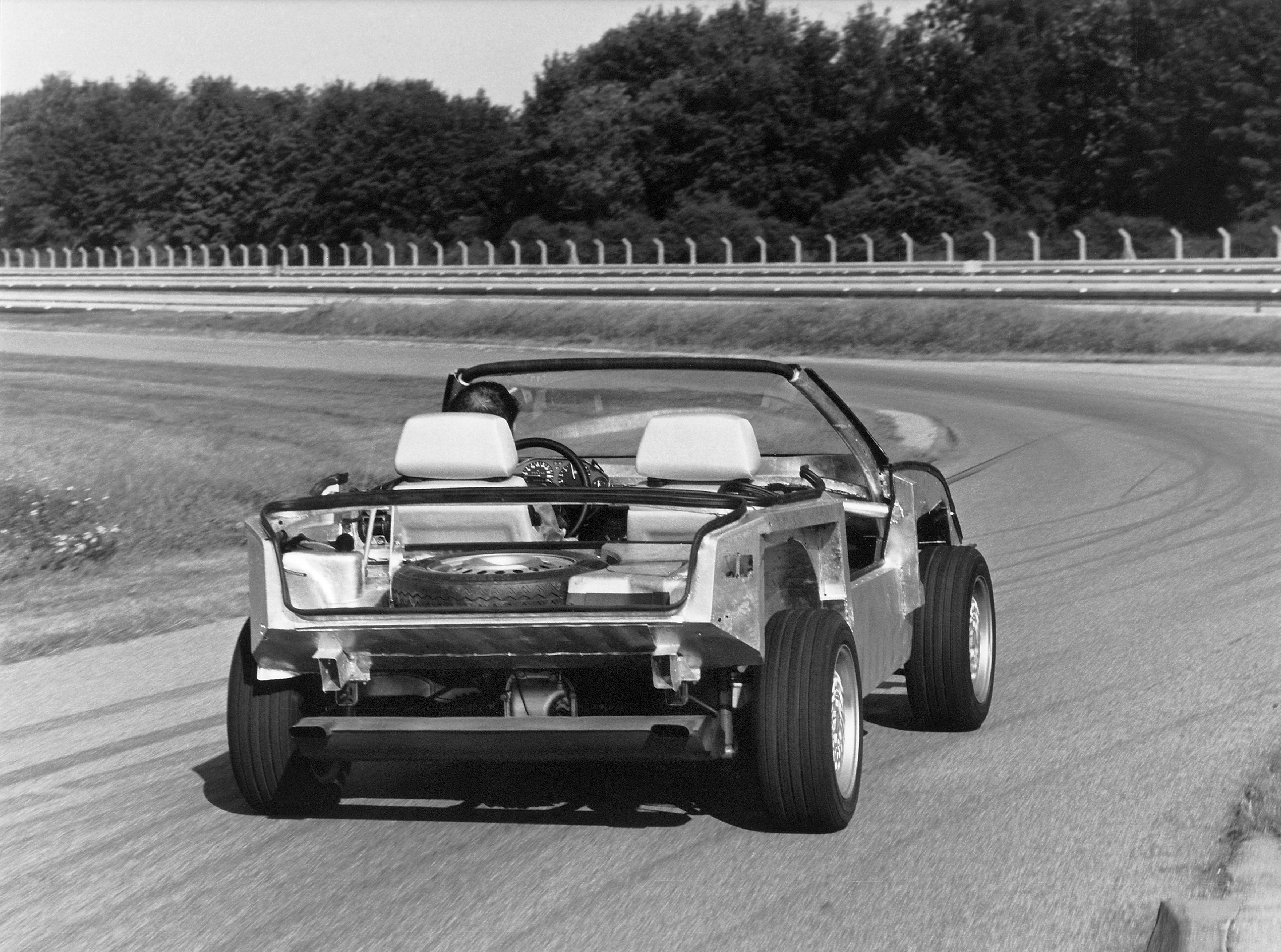

What was (other than the doors, and that you could drive around with them down) was that the body panels weren't exactly structurally integral to the car. You could drive around without them on if you wanted. Many a development engineer did, by the looks of the photos that BMW's historical archive sent me.

These panels were lightweight as well, and dent-resistant, as the excellent owner's site BMWZ1.co.uk recalls, paraphrasing BMW's own retrospective:

This was highlighted at the launch by the then Director Ulrich Bez, who gave a demonstration of the benefits of the plastic panelling, he jumped with both feet onto a vehicle wing lying on the floor, which promptly buckled and sprang back to its original shape when he stepped off.

The Director of BMW Technik GmbH at that time, Ulrich Bez, gave an emphatic demonstration of the benefits of the plastic panelling: he jumped with both feet onto a vehicle wing lying on the floor, which promptly buckled – then sprang back to its original shape when he stepped off it again.

The idea, according to BMW, was that this was something of a modular car, an idea that made its first big waves in Italian design but was getting some more play in the exploding Bubble Era Japanese auto industry at the time. The 1987 Mazda MX-04 concept that predated the Miata was like this as was the Nissan Pulsar NX, the one that lets you change out its coupe roof for a station wagon back if you want.

BMW figured that since these panels weren't a structural part of the car, you could just swap them all out, as it noted in its own corporate history:

Resilient and proven to be immune to damage, the panels were bolted into place. In theory, with a complete second set of outer panels it would have been possible to convert a Z1 from red to blue in the space of an hour using nothing more than a screwdriver.

This was, well, not true.

Actual owners on BMWZ1.co.uk say that it's more like two days work, as there are... I don't know, 19? I count 21 panels to tease out based off of a couple different official photos from BMW's archives. That includes the headlights themselves, but doesn't count the color-matched bucket seats that came in the car.

It was more expensive than expected, at 83,000 Deutschmarks as opposed to an initially-advertised 80,000. That made it something like two or two and a half times as expensive as an E30 with which it shared parts, per E30 Zone's collection of pricing of 1987. Only 8,000 Z1s ever got made.

It did start BMW's tradition of Z cars, giving way to the Z3, Z8, and Z4s, but its premise didn't exactly catch on. The only people driving around today with the doors down and all the body panels off their cars are old Z1 owners.

Ultimately, the Z1 wasn't exactly a car of the future we got. It was, as I say in the little history video above, a lot cooler than that. It was a car of a future I wish we got. Not all that complicated from a technical standpoint but bizarre from a packaging perspective, interchangeable, optimistic, and most of all, weird.