Yes, folks, I bought a $300 motorcycle off Craigslist. It was a risky move, and one that required nearly an entire year worth of wrenchin’. It was a trying ordeal, and I wouldn’t recommend it to the faint-of-heart, but what I learned from this junker I wouldn’t trade for the world.

The Impulse Buy

In my usual tradition of surfing Craigslist for 12 hours a day (I wrench the other 12), I came across this awesome 1981 Suzuki GS550L. A perfect first bike! It’s not too fast, not too slow, has good aftermarket support, low seat height, classic styling: how could it get any better?

So I called up the seller and he told me something to the effect of “It turns over but doesn’t fire. The title doesn’t have my name on it. I don’t have a key for it, I stol....” blah blah blah. I wasn’t listening. He said it turns over, so that’s good enough for me.

I drove down to Nine Mile Road just north of Detroit and met the seller at his home. The dude was working on a Chevy S10 and needed the bike out of the way. He cranked her over with a screwdriver, and I immediately fell in love. There may have been a giant plume of smoke coming from the electronics, but the heart wants what it wants.

“I’ll take it!” I said. And I loaded her up.

The Electronics from Hell

Once I got her home, I realized that maybe my love had blinded me to the fact that the bike had actual problems. Or that maybe I should have listened to the seller. In fact, I discovered that perhaps a better description than “motorcycle” would have been “conglomerate of parts shaped as a motorcycle.” Still, I was confident I could get her all fixed up.

I first had to figure out what was going on with those electronics. The lights didn’t work, the horn didn’t work, the gauges didn’t work. Frankly, nothing worked except the starter, which only cranked if you shorted the solenoid with a screwdriver, an event that was always accompanied by a sizable plume of smoke.

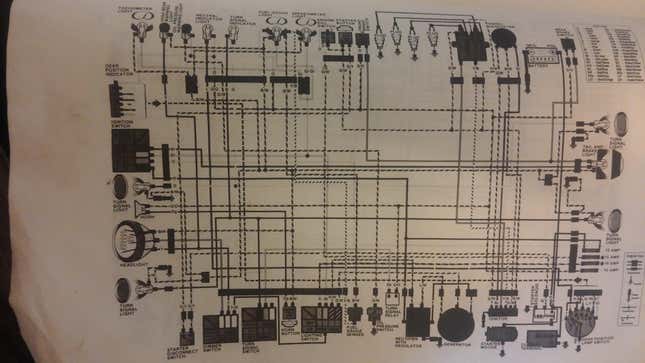

The wiring didn’t seem complicated until I started unplugging things and forgetting where they went. Eventually, I had to do something horrible. Something wretched. Something so unpleasant, mothers called their children inside, birds stopped chirping, and the sun cowered behind the clouds: I had to break out the wiring diagram.

That mess you see above sends shivers down mechanics’ spines. That’s a black and white wiring diagram. They’re illegal in 12 states (not really, but they should be).

See those different kinds of dotted lines? Well, each pattern represents a wire color, and it’s nearly impossible to distinguish the patterns from one another. To top it off, all of my wires were random colors, as the previous owner swapped them willy nilly. After weeks of trying to figure out the wiring, I caught a break in the form of a hilariously cheap parts bike.

The Parts Bike

Seventy-Five Smackers! What a deal! Yes, I paid only $75 for that parts bike. And it came with a title! I swapped over the electronics, had a key made for my ignition switch, and Bob was my uncle. My electronics were in tip-top shape.

The Seized Engine

Now that the electronics were fixed, I slapped on the ol’ carburetor, filled her with oil, put in new spark plugs, and tried to fire her up. No dice. The engine cranked and cranked, but no ignition. I pulled a spark plug, held it against the cylinder head, and turned the engine over: there was spark. So it must have been a fuel delivery problem.

I sprayed copious quantities of starter fluid into the cylinders, but still no explosions. I was at a loss. That’s when I had to leave for a work trip. (I used to work as an engineer for the “0.5” part of “The Big 2.5.”)

Fast forward two weeks, and I’d just come back from an awesome trip that included some pretty sweet Moab off-roading goodness. I went to turn the bike over, and now she wouldn’t even crank. Even after charging the battery, the starter wouldn’t spin. My engine was seized. Long story short, my liberal use of starter fluid wiped the cylinder walls dry, and my piston rings were stuck. I had destroyed my engine. Rookie mistake!

So, stubborn as I am, I decided to try to “free up” the motor. I pulled the cylinder head, filled the cylinders with ATF (this is an old trick), and slapped a breaker bar on the crankshaft. Even after pulling with all my might, I couldn’t get those piston rings free.

Parts Bike To The Rescue

Somehow, up to this point, I hadn’t thought to toss the engine in from the parts bike. (I never said I was good at any of this!) But after being unable to free up the seized engine, I decided to go ahead and yank the parts bike’s motor. It was no easy task.

The idea went like this: I’d unbolt the engine, tip the bike over, and simply pull the frame up, leaving the engine in place. It didn’t really work like that. Not only was the frame insanely heavy, but the engine was sandwiched into the frame very tightly. It was almost as if the frame were built around the engine. I had to unbolt the oil filter cover, and carefully shimmy the engine out. After much wrangling, I was able to extract the engine.

It took weeks to bolt the donor engine into the other frame. I had to reference old pictures to remember where all the brackets went, how linkages went together, and how wiring should be routed. And everything had to be torqued to spec, of course. But, in the end, I was able to transplant the engine without major issues.

Having The Carburetor Rebuilt

With the new engine in, I figured I’d have the carbs done for good measure. I tried fixing a carburetor once on a 1966 Ford Mustang. It didn’t work out so hot.

This GS550, though, has four of them. Four. Just look at that alien-like line of carbs, with fuel lines sticking out like tentacles. After a half-hearted attempt at rebuilding them, I sent them out to a guy on a forum. He rebuilt them, sent them back, and I installed them. It leaked everywhere.

Eventually, though, he sent me a functioning set of carbs, and the motorcycle ran.

What I Learned From The Ordeal

When it was all complete, I had spent more than $1000 on the Suzuki. Between the parts bike, a set of new tires, the rebuilt carbs, and various odds and ends, it wasn’t the budget bike I was hoping for.

It would certainly have been cheaper and easier to have simply bought a functioning $1000 bike, and many people might recommend buying a functioning bike as a first motorcycle. But I did learn a lot from it all. I know the bike inside and out. If anything breaks, I know exactly how to fix it. And there’s some value in that.

I still ride the bike around the Detroit area when it’s nice outside (which, frankly, isn’t very often). It rides like an absolute charm. With a redline of 9,500 rpm, the engine loves to rev. Above 5,000 RPM is where the four pot really gets into its own. The power surge above 5,000 rpm is so distinct, it almost feels like there’s some variable valve timing goodness going on inside that case. The beautiful noise up high in the rev range, exacerbated by my megaphone aftermarket exhaust, is so pleasant, it’s a miracle I ever shift past first gear.

The six speed transmission is crisp and smooth, and if I want to keep the bike quiet and civilized, I just shift early. Though it’s a bit heavy under braking and in turns, it feels quick in a straight line. The suspension is Cadillac levels of buttery and the seat is very comfortable. More than anything though, that classic Universal Japanese Motorcycle styling just smothers this bike with soul and character.

But to all those wide-eyed folks out there drooling over that $300 motorcycle that “turns over just fine,” hear my warning: it won’t be easy, and it won’t be cheap, but you’ll gain more knowledge than you could ever imagine.

Also, take it easy on the starter fluid.