Honda's Four-Wheel Steering Test Mule Was Better Than You Knew

It's really the most obvious solution, so much so it's hard to believe that's what they did

Four-wheel steering seems to be making a bit of a comeback, with GM announcing that its upcoming electric Silverado will offer it as an option. The lure of all wheels being able to turn has been around for quite a while, popularized by Honda's clever mechanical 4WS setup on the Prelude back in 1987. While we've covered the Prelude's 4WS system before, it wasn't until today that I knew what Honda's 4WS test mule looked like, and it's so much better than I dared to hope.

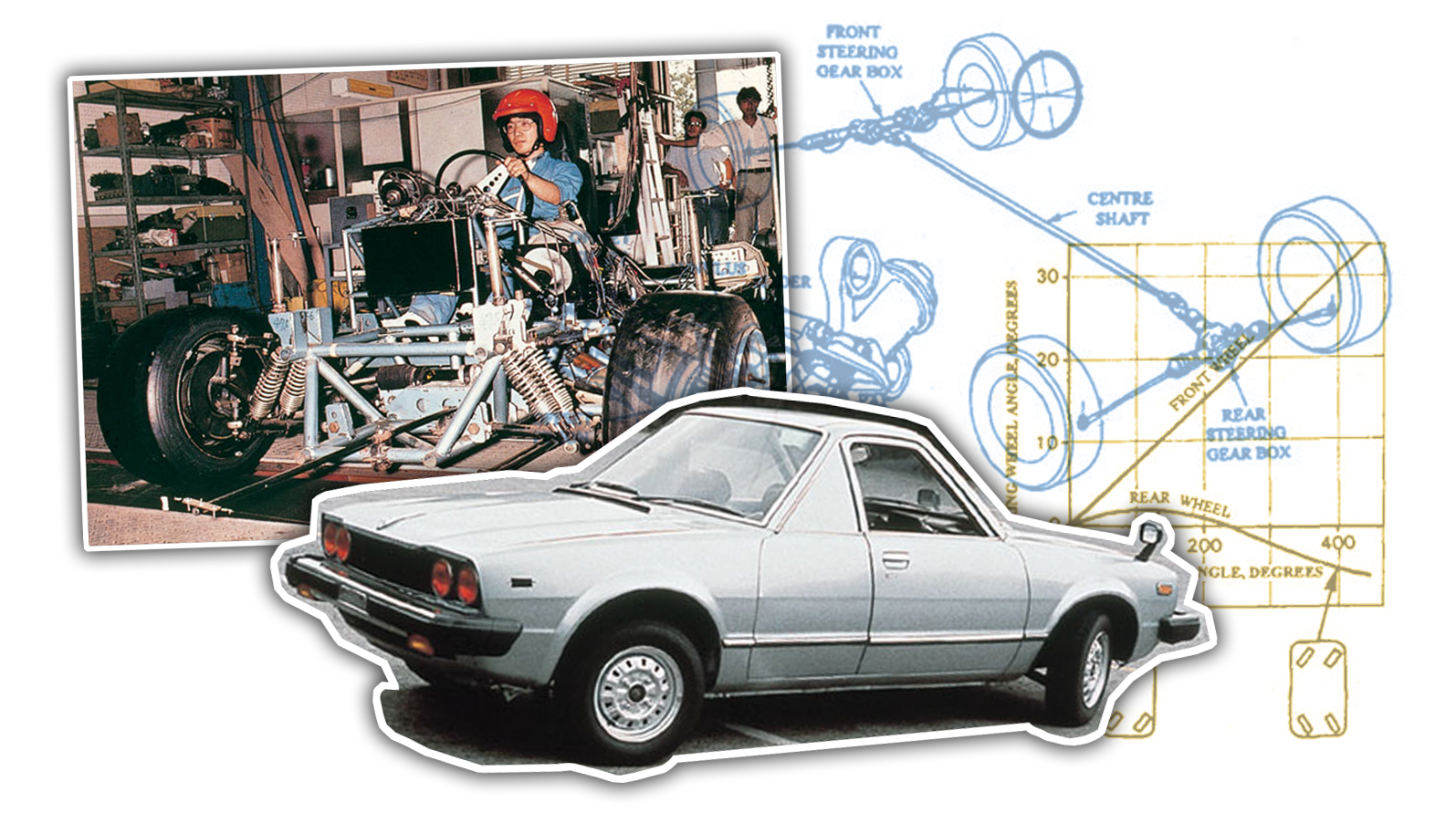

That's because it looked like this:

Yes, Honda just took a pair of Accords it had lying around and cut them in half, then Frankenstein'd them together to make their all-wheel steering test mule. Here's what Honda says about the car:

The two partners made rapid progress, and soon they were ready to test an actual vehicle. In April 1981, the first drive test was carried out on the west course at Suzuka Circuit. The test car was built from two Accords whose front sections were cut off and welded together to make one vehicle. The link mechanism that interconnected the front and rear steering mechanisms came courtesy of Oguchi and his students, who had fashioned it by hand.

The 4WS test car created by fusing the front sections of two Accords. Putting together two front sections, instead of modifying one complete vehicle to four-wheel steering specifications, greatly enhanced the progress of development.

Now, the more you look at it, the better it gets. First, it's not really just a pair of Accord front ends back-to-back, like other dual-steer weirdos we've seen before; it's clearly got a front and rear, with seats that just face one way and one actual steering wheel — the rear half's steering rack is connected to the front via the prototype of the transfer case/steering output shaft-type system that would be developed.

Also, note the rear's headlights have red lenses to make them taillights, which, excitingly, suggests that Honda intended to test this thing on public roads, which is a wonderful image.

Really, they sort of made a very cool little Accord coupé with a cramped cabin and massive trunk.

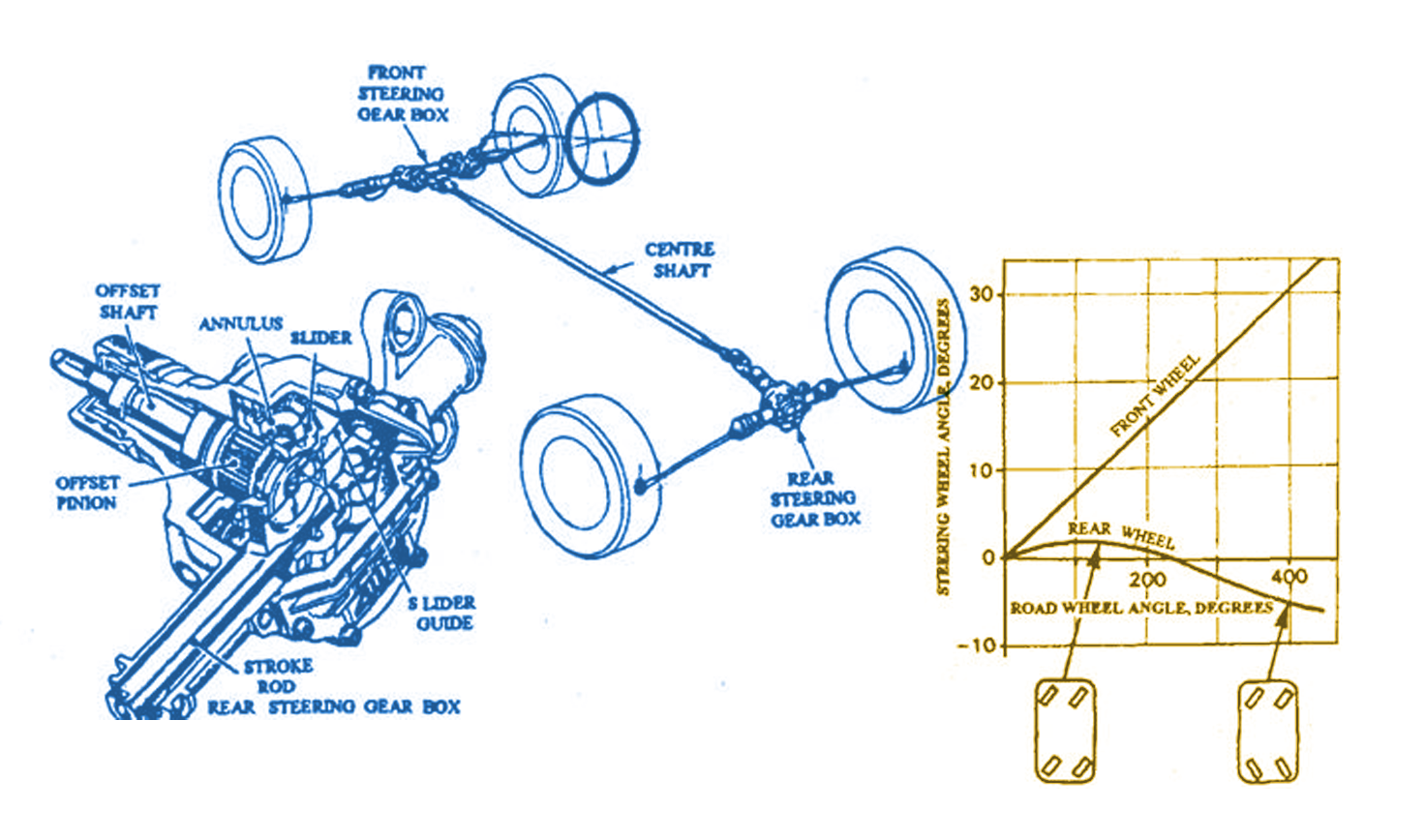

The original Honda all-mechanical system was really clever, with the rear wheels turning in sync with the fronts for low steering angle inputs (like you'd use at high speeds) and opposite for very high steering angle inputs (like you'd use for low speed, parking-type maneuvers).

Also fascinating to see is the early R&D that was being done to validate the fundamental concepts. An assistant professor Oguchi at Shibaura Institute of Technology had a team and a lab researching it, and were approached by Honda's researchers to team up.

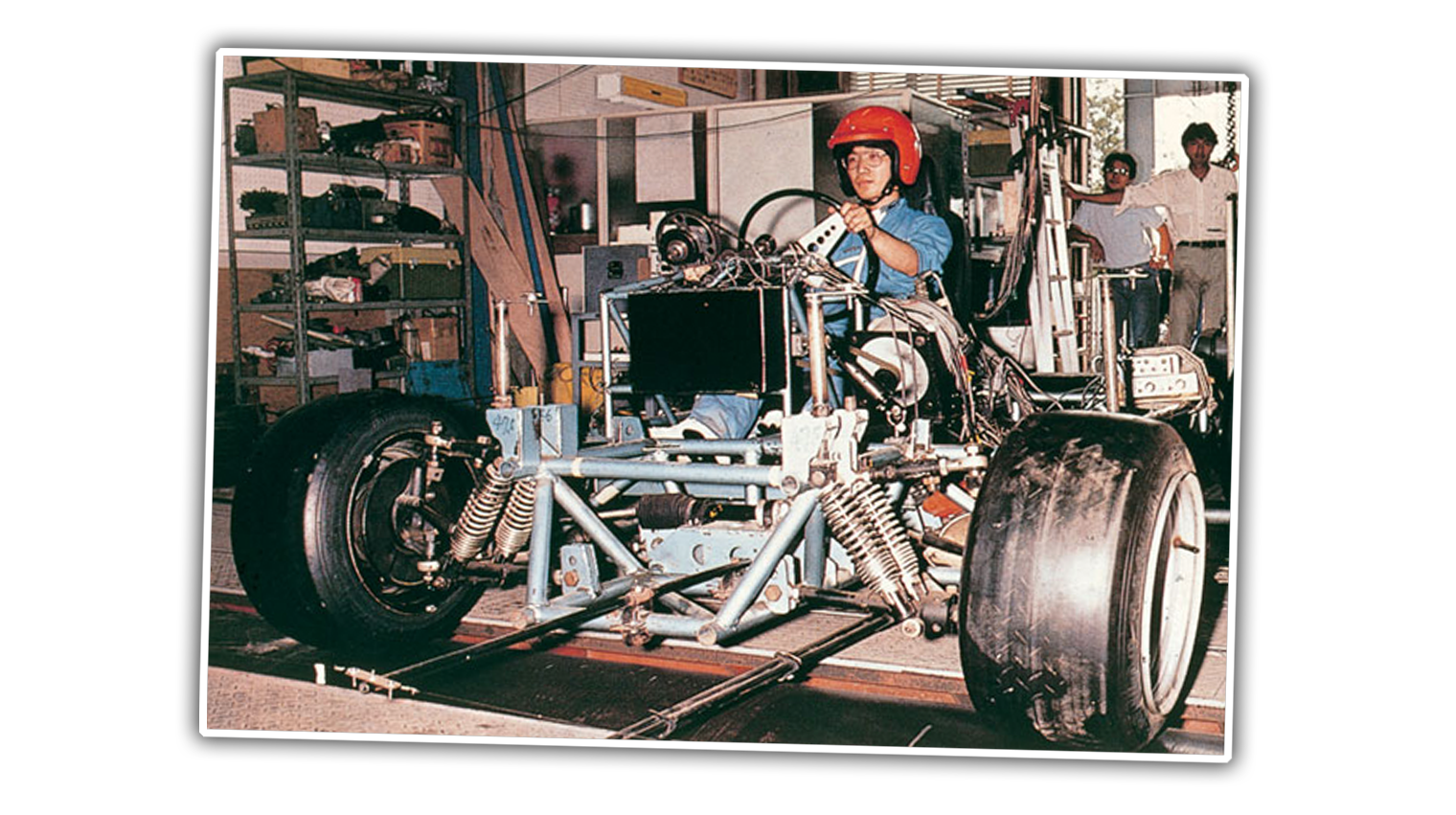

A crucial point came when the combined team used something called a drum-type bench tester, which looked like this:

Honda's heritage site gives a bit of background on this fun-looking contraption:

A key benefit of the joint research was the drum-type bench tester installed in Oguchi's laboratory. It was a device made of two drums placed in parallel at the front and back. A test car made of pipe frames was placed on top of the tester. The tester could evaluate maneuverability and stability under various conditions by changing the gearbox setting in order to obtain the desired steering ratios for the front and rear wheels. With this device Sano and Furukawa could substantiate their theory through the collection of quantifiable data. They also acquired other data, including an optimal steering ratio for the rear wheels. This proved very useful when filing the patent application for their aforementioned technology.

From what I can tell, it looks like this is similar to a roller dyno, but with powered rollers to move the wheels to simulate driving. There's a lot of pulleys and belts and all kinds of exciting things going on there, too.

Honda's clever system that allowed for speed-sensitive all-wheel steering without any sort of complicated electronic control systems still impresses me today. And now that I've finally seen the equally clever and simple and gleefully ridiculous-looking test mule that proved it, I like it even more.

Though, if I'm honest, I tend to think most 4WS systems are more complexity than benefit, but, you know, let's not spoil the mood.