I Visited Supercar Company Koenigsegg After Sleeping In A Van And Bathing In The Sea

I showed up to Koenigsegg's Ängelholm, Sweden headquarters smelling like fish

"It's so cold!" I couldn't help but yell as I resurfaced from the chilly Baltic Sea, having lost my glasses and wearing only underwear. I lathered soap on my body as quickly as I could, not just to escape the painfully frigid water, but because I had an appointment at Swedish supercar company Koenigsegg's headquarters. I was running late.

How did I end up in this dumb situation, glasses-less, mostly-naked, and shaking uncontrollably in the Baltic, running late to a meeting with one of the world's leading automotive engineering companies? Well, it all started last summer after my friend Andreas agreed to purchase a 250,000 mile diesel, manual 1994 Chrysler Voyager on my behalf.

The incredible machine was located in Germany, and I was in Michigan. Adding to the inconvenience, the van wasn't running and, unbeknownst to me at the time, had bad wheel bearings, a broken axle CV-joint, failed suspension and shifter bushings, and a whole slew of other problems. I spent a month diligently fixing the car in a garage just north of Nürnberg, and in time, managed to get the American-designed, Austrian-built, Italian-engined van road-legal after two failed attempts through Germany's rigorous TÜV inspection. It was now time to put the diesel manual family vehicle to the test.

My first trip, which I've already written about, took me to the German cities of Frankfurt, Düsseldorf, Cologne, and Aachen, as well as to Ghent, Belgium. I met some great car enthusiasts and learned a lot about car culture in these places, but most importantly, I discovered my minivan's excellence. The vehicle cruised the Autobahn confidently, with a smooth ride and surprising efficiency.

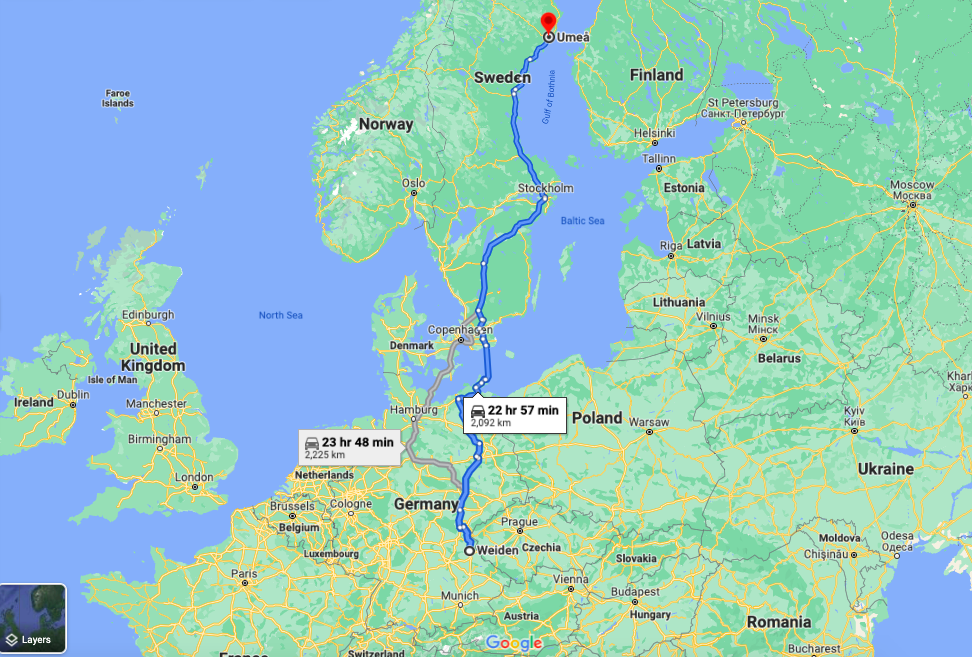

That was only a 1,000 mile round trip, though — not nearly long enough given the hellish wrenching I'd just endured. After all that toiling, I wanted to really see what the $600 minivan had left in it, so last fall I set out to drive from my parents' place in Germany to a small town near Umea, Sweden, where a reader had (I think jokingly) invited me.

Sweden, it's worth noting, was one of few countries not on Germany's COVID "Riskogebiet" list, meaning I could travel there and return without having to quarantine.

To get to Sweden, I hit the Autobahn and drove straight north for six hours to the city of Rostock in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. This city is Germany's largest Baltic port.

When I arrived, I drove up a giant ramp onto a ship headed to Trelleborg, Sweden.

The Ferry From Germany To Sweden

I parked the van in the hull (see arrow above), and — since it was quite late — caught a few z's on a chair in a seating lounge. I made sure to keep away from other travelers, as this was all during the fall of 2020, peak COVID season.

My van and I landed in Trelleborg at around 6 A.M. I was still dead tired, but staying on the vessel wasn't an option, so I hit the road. I lasted maybe 20 minutes before assuming a horizontal position at a Qstar gas station.

The photo below shows my lodging arrangement. There's a green foam sleeping pad, a sleeping bag and a pillow. That's it. When I initially started this van project, I had resolved to turn the van into an overlanding beast, with drawers and a nice shower setup. But I was too impatient. Europe beckoned, and the VM Motori 2.5-liter turbodiesel matched to a fantastic Chrysler five-speed manual transmission begged for miles after years of dormancy.

The following morning, I was off to Gothenburg, home of Volvo, employer of a Jalopnik reader named Nicholas, with whom I had scheduled a meetup. Nicholas is an engineer whose expertise is in — and I'm quoting him here — "engineering processes, methods, and tools for developing software for the electric drive, battery, and charging systems in all electrified vehicles in the Volvo Car Group." That's legit.

More importantly, he grew up near one of my hometowns in Kansas, and he seems like just a good dude.

Gothenburg

When I arrived in Gothenburg, the former Apple engineer showed up in a red plug-in hybrid Volvo, showed me around the automaker's campus, taught me a bit about how things operate at the safety-obsessed car company, and walked me through how he ended up in Sweden from Kansas.

Here's a snippet of his journey from an email he sent me later:

I was just shy of my five year anniversary at Apple when due to Reasons I felt it was important for me to find a new challenge. I have always been a car guy, having owned a whole bunch of Benzes ('73 450SL, '78 450SL, '84 300SD Turbo, '86 300E, '08 SL550), a whole bunch of Volvos ('87 745GLE, '87 745T, '88 744GLE, '94 850 Turbo, 02 V70XC, 15 V60 Polestar #2/80), and a few other oddities ('83 Chevy Suburban C10 6.2 Diesel, '98 VW GTI unofficial Drivers Edition, '12 Subaru STI wagon, '13 VW Jetta Sportwagen TDI). Maybe it would be a good idea to see what I could do in the auto industry since suddenly computing in the car was becoming a big deal.

[...]

Today I work in the Base Product Development team as a Software Architect. Mostly I am involved in how we will use high performance computing in our future vehicles and how we can use concepts from the tech industry in the automotive world. I also teach classes on software configuration management, code review processes, and continuous integration. It has certainly not been the path I expected, but it has been an adventure and I feel that right now I am where I need to be. Of course, I still have interesting cars: a '02 Peugeot 206CC 2.0 (with GT body kit), '03 Volvo V70 D5 M56, '21 Volvo V60 T8 RDesign (that you drove), and my research car: a '19 Polestar 2 verification prototype that has become frankensteined with various prototype phase and production parts.

Gotta love it when car-people like us work in the industry, don't you?

Anyway, after I left, Nicholas suggested I get a local delicacy: Kebab pizza. This confusing blend of Turkish and Italian culinary culture combines tomato sauce, onions, kebab meat, and a mysterious white kebab sauce and places it all atop pizza dough. (Note: After this Sweden trip, I took the van on a hellish drive from Germany to Turkey. I've already written about this trip, but what I didn't mention is that at the wedding I attended there, I was privy to a conversation wherein Turks were trying to figure out what the hell the white sauce is that western Europeans (namely Germans) drizzle on Döner kebabs. Nobody knew). The pizza was great... until I got three quarters (three pie over two, for you engineers who see life in radians and enjoy a good pun) of the way through; then I couldn't stand another bite.

I spent a second day in Gothenburg hanging out with a different Nicholas, whom I'd worked with back at Chrysler in Auburn Hills, I think on the RU (Chrysler Pacifica) program. He and I, plus a reader named Michael (who wound up in Sweden thanks to a former job at Amazon, and who stuck around to build a family) hung out late into the night, tranquilly enjoying dinner under a bridge.

We three Americans (well, a Canadian, a British-America, and a German-American) walking along Swedish docks, talked about our life experiences, and connecting on an intellectual and almost spiritual level.

Even though the big "highlights" like jumping into the sea (more on that in a second) and seeing cool supercar hardware (more on that in two seconds) are the most exciting parts of a trip like this, the in-between moments like this one with Nicholas and Michael are immensely transformative. Even if they don't make for great stories to repeat at parties or in a blog.

Anyway, back to the highlight reel, and how I ended up near-nude off the side of a Swedish highway.

Koenigsegg

It was 45 degrees at a rest-stop near Gothenburg, Sweden, where I had just spent the night in the back of my diesel 1994 Chrysler Voyager minivan after having finished writing a silly article bumming Wi-Fi in a Burger King parking lot. Wearing flannel-lined jeans and a winter coat, and rolled up in my sleeping bag, I didn't want to get up, but I had no choice. It was 8 A.M., I had an appointment at supercar company Koenigsegg's headquarters in Ängelholm, Sweden two hours away, and I still needed to find a place to shower.

A wiser man would have gotten a hotel for the night, but hotels in Sweden aren't cheap. I am. Plus, this was supposed to be an epic van trip, not an epic van-and-hotel trip. More importantly, if I'm not going to sleep in this van, then what's all that space being used for? Answer: Nothing. It's being wasted.

I won't stand for that.

Anyway, for reasons I should probably discuss with a professional, I surmised that the best way for me to bathe prior to meeting with Koenigsegg was to jump into the Baltic Sea (technically the Kattegat strait between the Baltic Sea and North Sea). As you can see on the map, the route from my rest stop near Gothenburg to Koenigsegg HQ in Ängelholm took me right along the water, and my full logic train was this: "Water = clean. Sea = water. Ergo, by the transitive property, Sea = clean."

Profound, I know.

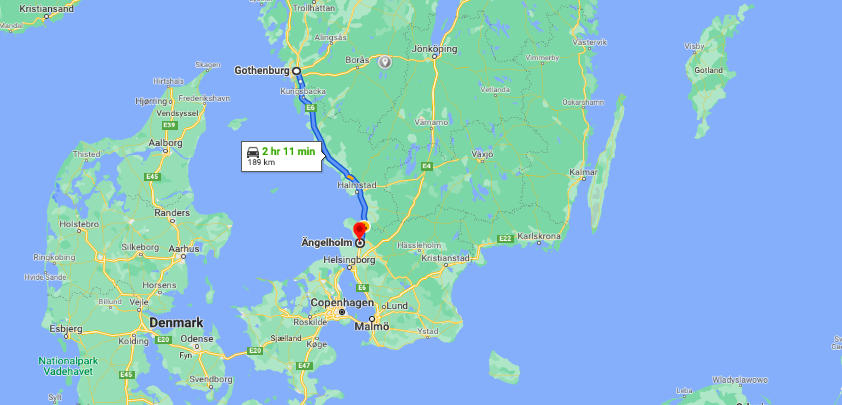

I bought some environmentally-friendly soap, turned off to a road near the water, and then did a bit of off-roading to get as close to the sea as possible, since it was 45 degrees and windy and I wanted to minimize my cold walk to and from my bath:

The water smelled like fish, and my entire body recoiled as soon as I stuck my big toe in. But this was a professional meeting I was about to have with engineers. I couldn't show up smelling like I'd just spent the night in a 1994 Chrysler minivan — Koenigsegg would notice right away! So, against my body's instincts, I undressed in the back of my van, jumped into the water, and wiped myself down with eco-friendly soap as quickly as possible.

As you might surmise upon seeing the photo below (and video toward the top of this article), the dip was extremely uncomfortable. I don't know how cold that water was, but I think I lost about a foot of height and six inches of waistline from thermal contraction alone.

I ran back into the van, got dressed, and then quickly realized that I couldn't see a damn thing. I looked around, assuming I'd set my glasses down when I'd gotten undressed. I found nothing. I slid open the side-door and jumped out; maybe I'd set them down on a rock when I was taking pictures of the majestic van by the sea? No dice.

Then I had a thought. I jumped back into the van, threw my GoPro's SD card into my laptop, and began watching the film. "Oh shit," I realized. "I wore my glasses into the sea! Like a fool!"

Anyway, the glasses were gone. I luckily had a set of contact lenses to get me through the next few days, though I knew I'd later need to buy more without a prescription — possibly used ones from a back-alley optometrist.

I drove 90 minutes to Ängelholm, and arrived at a massive airfield with a flight museum nearby. Right next to the air strip sat a long white building, built in typical Swedish understated fashion. Three flags bearing the Koenigsegg crest waved proudly out front.

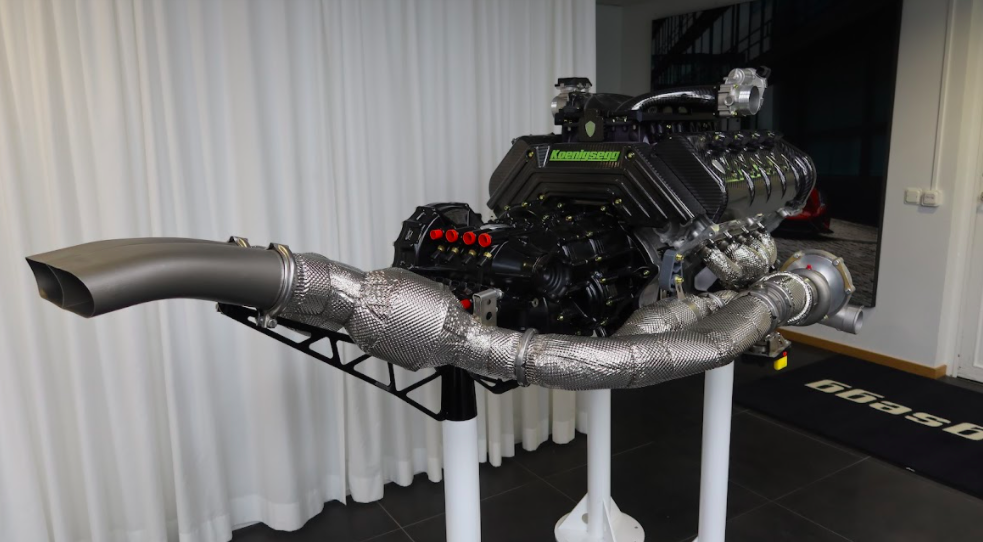

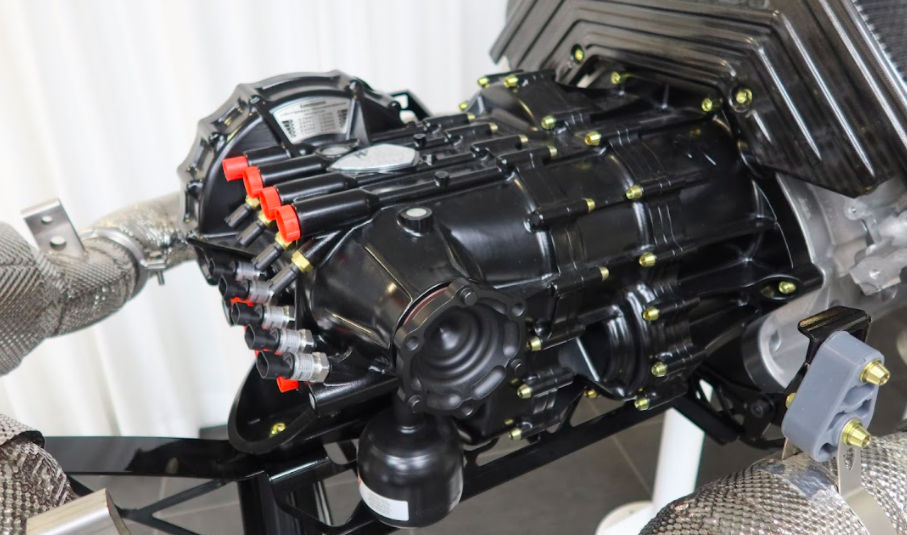

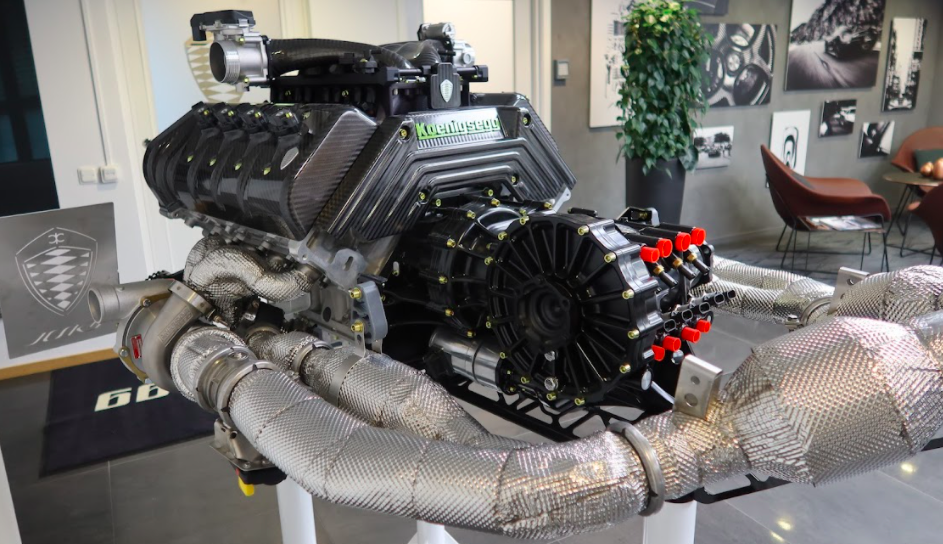

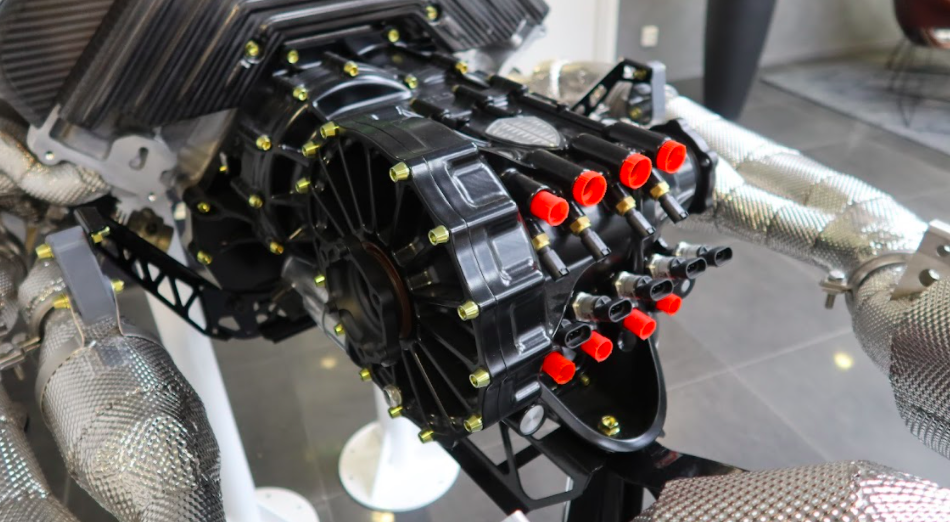

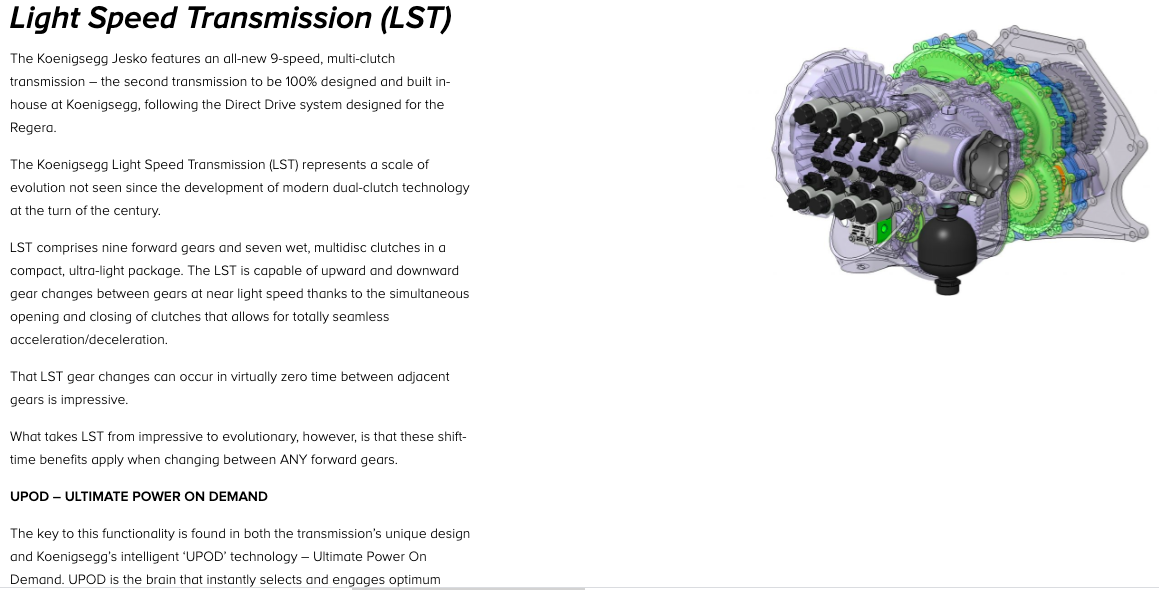

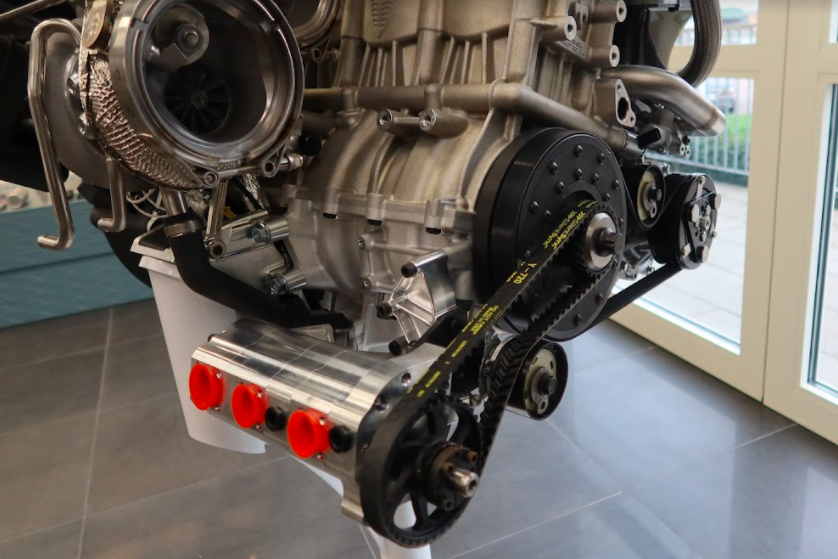

Upon entering the facility, I met with a Koenigsegg PR rep, and then with Ruben Lend, the company's lead engineer for braking, steering, and suspension. He was working on the nine-speed "Light Speed Transmission" found in the Jesko. This transmission, as with most Koenigsegg projects, is bonkers, as Jason Fenske describes in his article on Road & Track:

Dual-clutch transmissions (DCTs) work on the same principle. One clutch opens while the other closes, allowing for wildly fast shift times. The problem is that they can only preselect a single gear at a time. The ECU guesses which ratio will be needed next, preselecting a gear. If it's wrong, shift time suffers....

Instead of two clutches, the LST uses seven—eight if you count the differential that's part of the transaxle. These are wet, multiplate clutches with their own hydraulic actuators and pressure sensors. Each gear pair gets a clutch of its own, and the transmission uses three gear shafts instead of two, which allows for compounding gears.

[...]

Because each gear pair has a clutch, switching from one gear to another with the LST simply requires simultaneously opening and closing the respective clutches. It's like a dual-clutch that never has to predict which gear comes next; it's ready for whatever the driver wants. Koenigsegg calls this ultimate power on demand, or UPOD. The goal is to put you in the optimum gear for acceleration without hesitation.

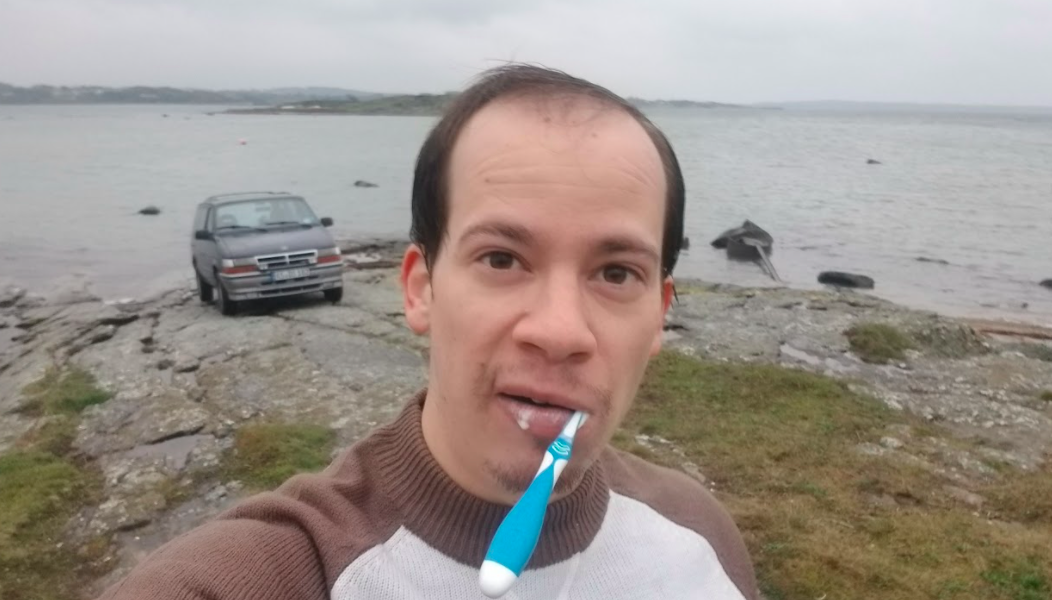

Lend was very focused on his work, to the point where he really wasn't divulging much to me. He had a CAD model on his computer, and it was clear to me that he had engineering to do. In any case, here are a few images I took in the lobby of the nine-speed bolted to the Jesko's twin-turbo 5.0-liter V8.

Looking at my notes from last fall, I have a few quotes from Mr. Lend about this incredible transmission. "We can jump from 3rd to 9th to whatever," he told me, saying if you're cruising in sixth and want to downshift, the car can jump to the lowest gear that keeps the engine below 7,000 RPM.

He said there are six pairs of gears (with nine forward and three in reverse), and seven clutches (with six forward and one for reverse). "[We] can choose which two clutches we are connecting at the same time," he said.

The reverse gear is what caught my interest, so I inquired further. "In theory, we have a reverse gear that could also drive in different speeds," he said. "Let's say that it could go fast in reverse," he continued, not specifying exactly how fast, but that it'd be above 150 km/h (that's over 90 mph). That's nuts.

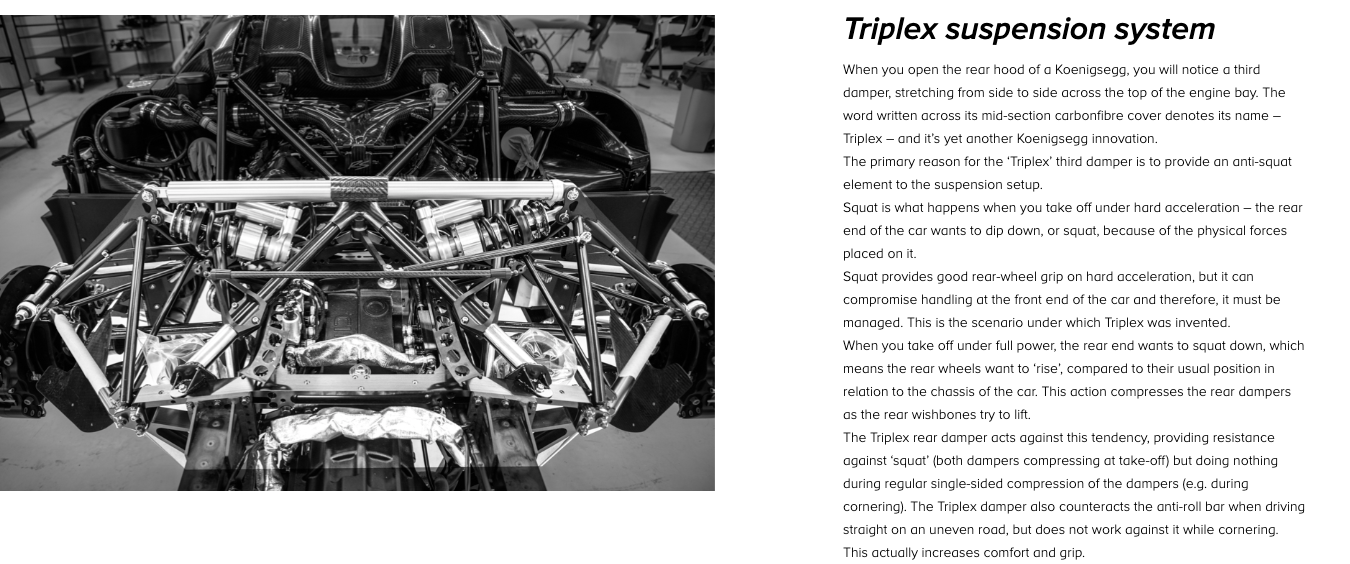

Lend also talked to me about the Triplex suspension found on Koenigseggs. This suspension utilizes a damper spanning from a suspension arm on one side of the car to a suspension arm on the opposite side. Per Koenigsegg's description above, the aim is to "[provide] resistance against 'squat' (both dampers compressing at take-off) but [do] nothing during regular single-sided compression of the dampers (e.g. during cornering)." In other words, the design is there to ensuring good grip at the front wheels even during hard acceleration, thus aiding with handling.

This YouTube video from /Drive describes how it works:

The Jesko is special in that it incorporates the Triplex suspension methodology in both the front and rear, meaning it "supports dive and squat," per Lend. Here's how Koenigsegg describes the Jesko's setup on its website:

Koenigsegg developed the Triplex Suspension system for the Agera in 2010. A third, horizontal damper added at the rear allowed the car to employ natural physics to combat squat – the tendency for the car's rear to lower itself under hard acceleration.Jesko is equipped with a second Triplex unit in the front suspension, extending this capability to the front of the car.

Jesko has over 1,000 kilograms of downforce available. The forward Triplex unit helps to keep the front of the car level, maintaining optimal ride height during high aerodynamic loading without compromising grip and handling at lower speeds.

Looking at my jumbled notes, I have a few other suspension-related quotes from the engineer. Lend talked about how you don't want a suspension that is too stiff or you'll lose mechanical grip, and he discussed the advantages of the Triplex system, saying: "You can still roll in the corners ... The whole idea is that the wheels independently can hold mechanical grip, but you're still keeping your aero platform." He went on to mention that, of course, it's critical to keep the nose from hitting the ground during braking, and that's an area where the front Triplex system helps.

Other discussions with Lend included the importance of controlling preload in the vehicle's drivetrain (it's especially important in high-horsepower cars to keep the vehicle well controlled), what the 10 solenoids in the Light Speed Transmission do (all I have in my notes is "one pressure, one safety, one differential, [seven] clutches" — not entirely sure what the all that means, but I'm assuming they're controlling oil pressure actuation to these components, though it's not clear what "pressure" and "safety" are), the benefits of an engine without a flywheel (among them: the engine revs quickly, allowing for fast gearshifts), and a brief mention of differential and gearbox cooling systems.

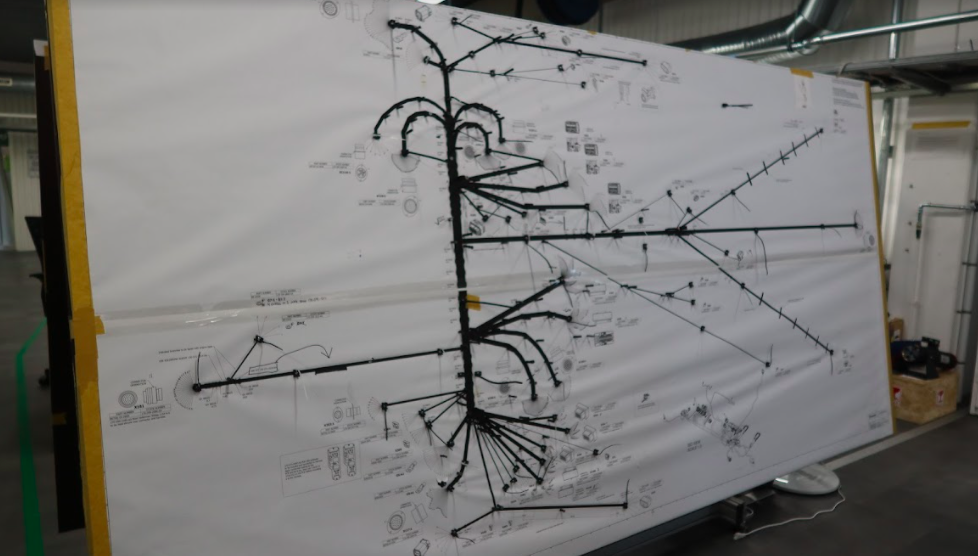

After that short chat with the clearly rather busy, but still brilliant and accommodating Mr. Lend, Koenigsegg's PR rep sent me on a tour of part of the company's production facility. I was restricted on what I could photograph, but I did snap this image of Koenigsegg's wiring harness schematic.

I have to say, I was surprised with how simple Koenigsegg's process is for assembling a harness. The team has a vehicle's harness outline printed on a big sheet of paper taped to a large board. Fastened to that board are zip-ties meant to hold wires as workers insert them to match the drawing, which also contains connector information (per my guide, the Regera has 2.5 kilometers of wires in total and roughly 4,000 connectors). This method is manual, it's simple, it's cool, and Koenigsegg says it uses it for two reasons: Getting suppliers to do such low-volume work is nontrivial, and doing the work in-house means better control over quality.

Also simpler than one might think is the way that Koenigsegg sews its fabric. The company uses human-operated sewing machines, though you may be surprised to know that this actually isn't uncommon, even among luxury automakers.

Plus, as you can see, this is no regular sewing machine, it's a Dürkopp Adler Delta. I just went down a deep rabbit hole learning about these ridiculously powerful German contraptions; I won't bore you with the details, since this is a car website, but suffice it to say that this machine does everything it can to make sewing error-proof. It guides the operator through exactly what needs to be done (the job at hand has been loaded into the machine), and even adjusts itself for each step of the operation.

The tour guide made mention of the precision needed to align the holes in the Swedish leather (which makes up much of the Regera's' interior) with the small holes in the carbon fiber speaker cover:

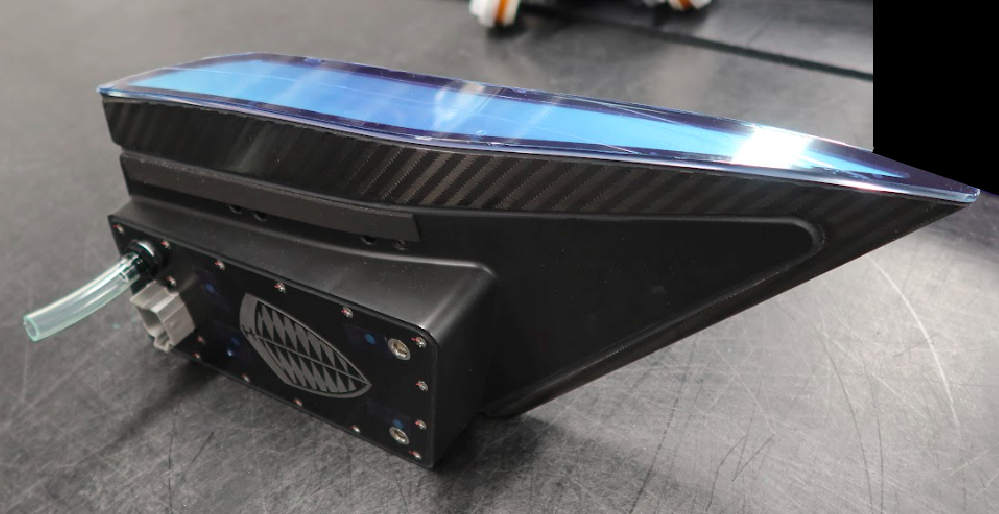

Upstairs I saw the preassembly area where smaller parts making up larger systems — parts like cooling modules (which consist of heat exchangers, shrouds, and fans) and headlights — were put together. I had a photo of this area, but Koenigsegg PR asked me not to include it because the area looked "untidy." I didn't find it untidy, but I'm a slob and Koenigsegg is Koenigsegg.

The lights are extremely intricate, and feature what appears to be integrated onboard electronics and some sort of hose whose function I cannot recall at the moment — perhaps something related to cooling?

Here you can see a headlight bezel (from a Regera if I recall correctly) in black, though customers can opt for it in a bright, polished style, as well:

Beautifully-polished parts like these are transported around the factory in a nice, padded suitcase like the one shown below carrying interior switchgear:

Look how fine the little holes are in these buttons:

I also got to see how Koenigsegg creates its carbon fiber components. There's a board in the hangar labeled "Carbon Quality" showing the different stages that carbon fiber goes through as it gets sanded and polished. These phases are necessary to create a surface finish that Koenigsegg refers to as "Koenigsegg Naked Carbon." This is carbon fiber that has been precisely sanded/polished in a way that yields an outer surface of pure carbon, free from epoxy. This is harder to scratch, but most importantly gives an awesome appearance. From Koenigsegg's press release about the Regera:

KNC involves no lacquer, varnish or alternative coating being used on top of the carbon surface. The thin layer of epoxy that normally covers a high-end autoclaved cured carbon piece is carefully removed by hand polishing. This is an extremely sensitive process; one stroke too many will ruin the visible weave structure underneath the thin epoxy layer.

The end result is a striking new look for carbon fiber. The body of the car becomes cold to the touch as the material is pure carbon, instead of an insulating epoxy or lacquer layer with carbon underneath. The sheen takes on a more metallic graphite appearance as each graphite strand is now fully exposed.

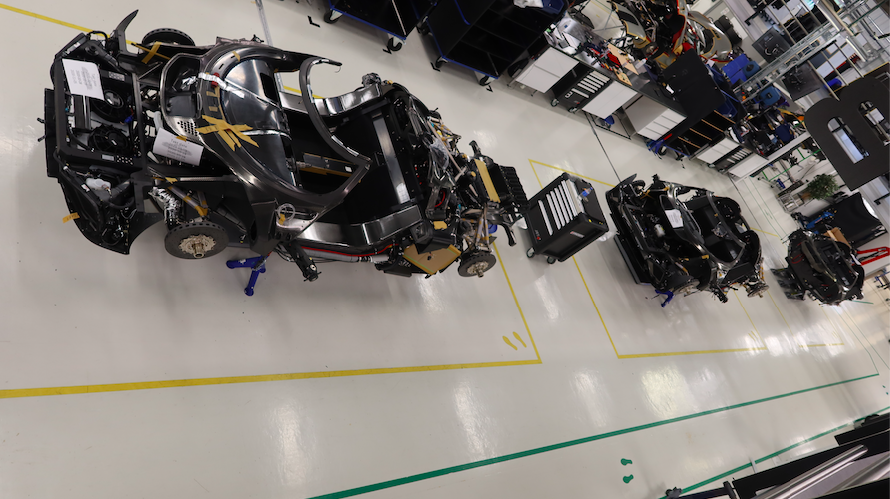

You can see some Regera chassis above; Koenigsegg was very particular about what I could photograph; I had to make sure not to zoom in too closely to the production stations.

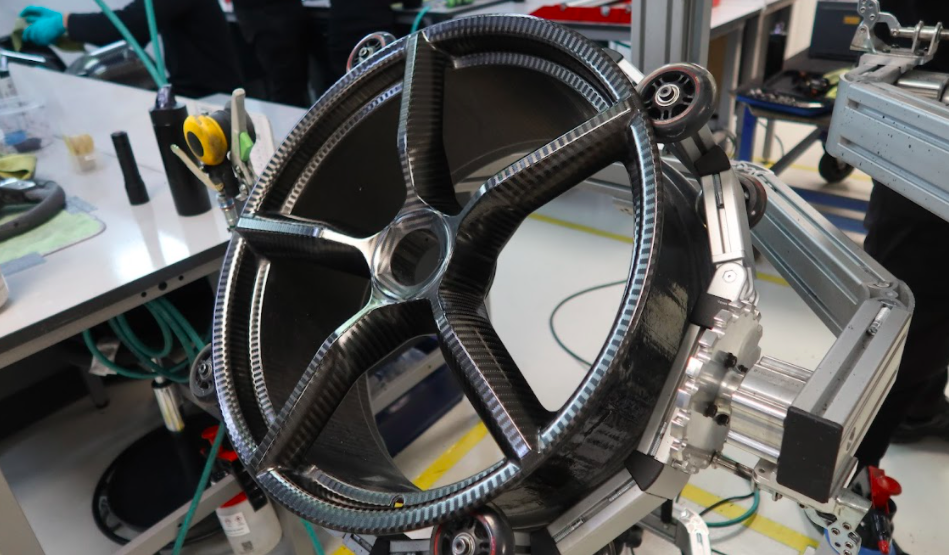

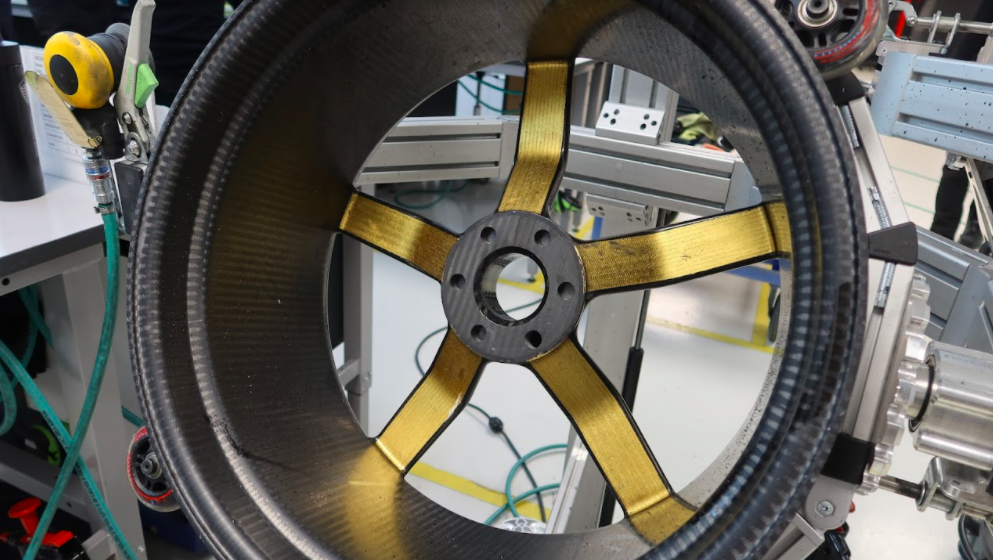

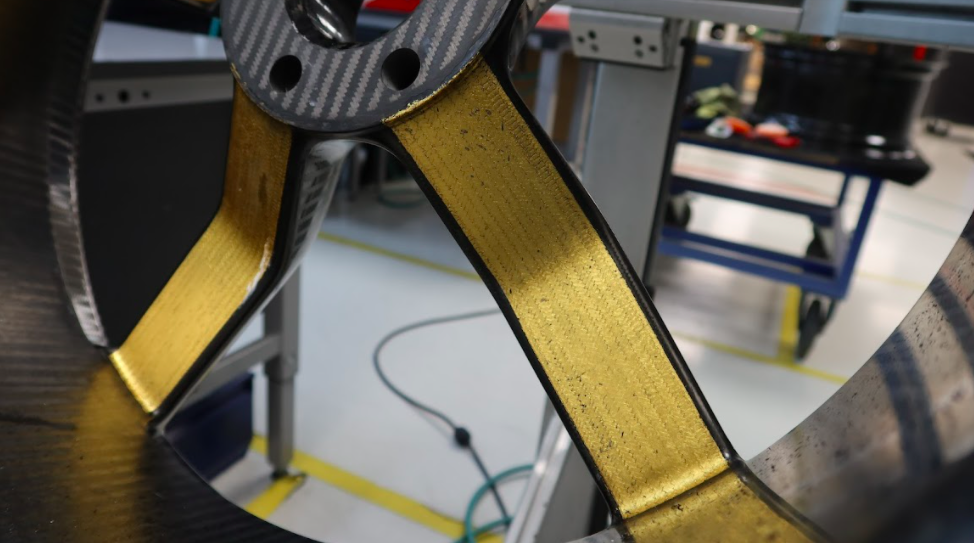

As you can see, there's carbon fiber everywhere. It's absolutely absurd. Look at these incredible wheels:

The gentleman guiding me through the facility said the 24-carat gold is there to protect the wheel spokes against heat from the brakes, though it is worth noting that the company also uses gold flake on its wheels as design accents.

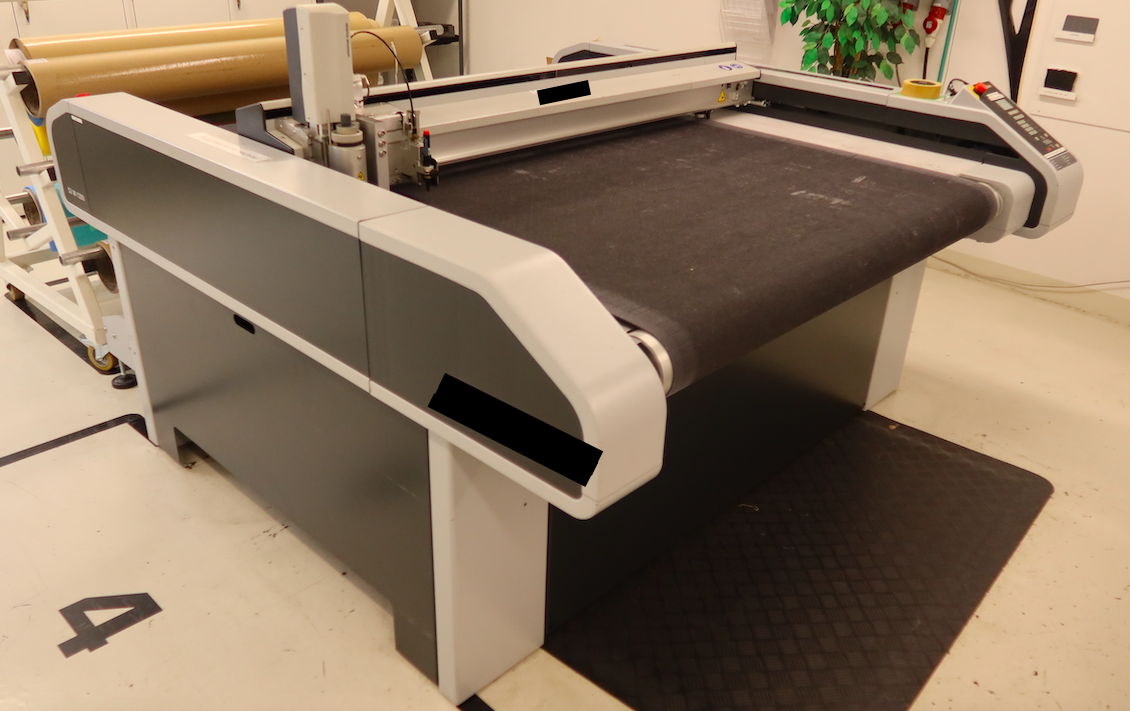

The machine above precisely cuts raw carbon fiber rolls into pieces, which are then carefully inserted into a mold, as shown in the /Drive YouTube video embedded below:

You can see in the video that the wheel spokes are hollow, which is important, as it allows for a lightweight design (which matters because unsprung, rotating mass is bad for handling, acceleration, and overall efficiency). If I understand correctly what my tour guide told me about these spokes, the carbon fiber is layered over some kind of plastic mold, which is melted out, creating a hollow void.

The video above shows a "breather felt" cloth wrapped around the carbon fiber layers; this is meant to minimize pressure points that would otherwise be exerted by a vacuum bag placed around the wheel, ultimately yielding a nice part without flaws. The felt and vacuum bag-covered wheel go into an autoclave, which raises temperatures to 120C and pressurizes to 4.8 bar, squeezing the epoxy out of the material. A CNC machine later cleans up the part to create the desired shape.

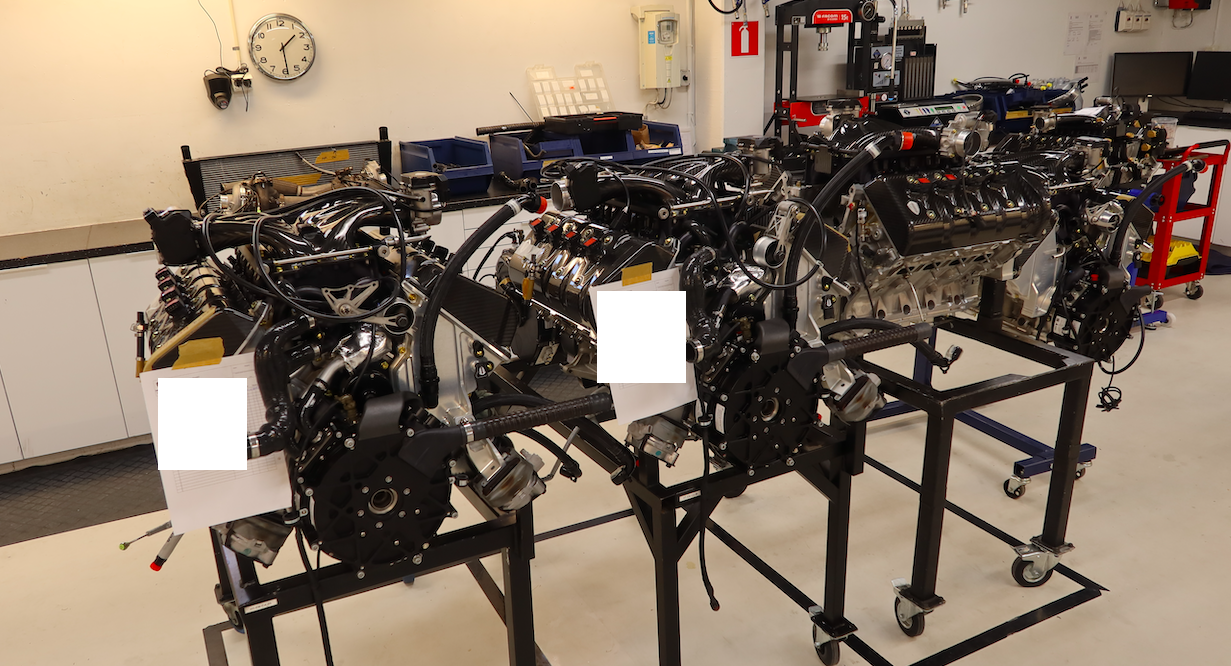

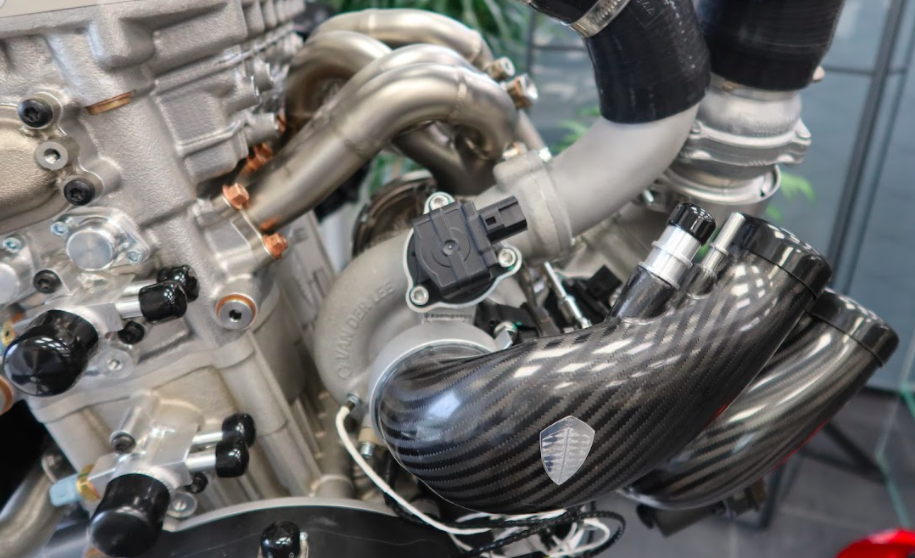

I also saw some hardware in the engine room; In my notes, I have written: "V-8: three days. TFG: one day." Presumably, this represents how long it takes to assemble the V-8 and the Tiny Friendly Giant, with the latter being the fascinating 600 horsepower twin-turbo 2.0-liter three cylinder found in the Gemera.

I got to see a lot of amazing stuff in that hangar, from gorgeous titanium Akrapovič exhaust systems to the Torque Converter-On-Steroids known as Koenigsegg Direct Drive (linked below) to the cool glue-and-bolt joints making up suspension attachment points on a monocoque, to the monocoque's carbon fiber integrated fuel tank.

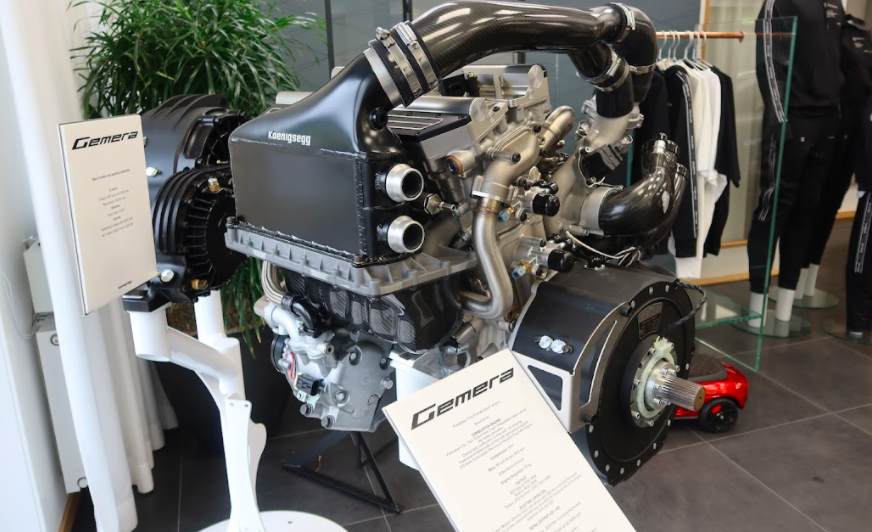

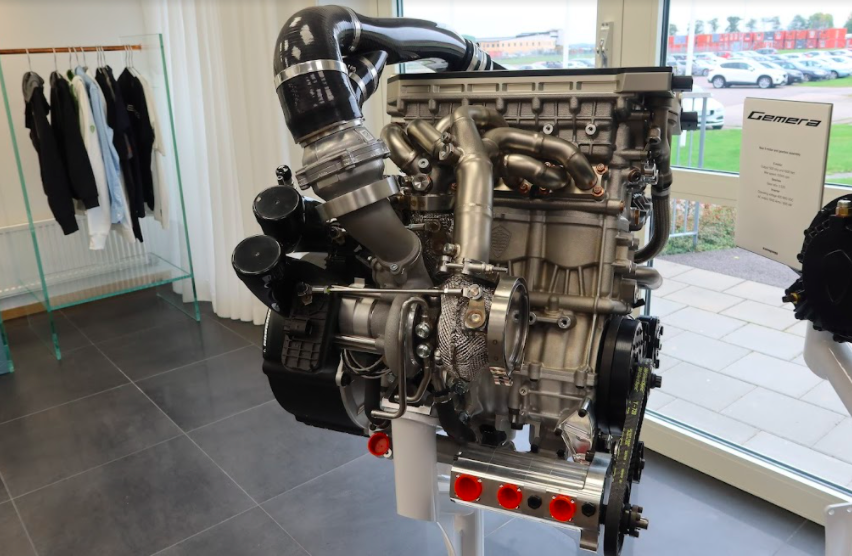

Outside in the lobby, Andreas Moller, sales and marketing manager representing Freevalve — Koenigsegg's sister company that engineers camshaft-less engine technology — walked me around the Tiny Friendly Giant engine and described how Freevalve works.

If you want to learn more about this fascinating tech, read my Gemera article. Here's a snippet:

Koenigsegg's Freevalve, also called "fully variable valve actuation," is different [than a traditional variable valve timing/lift system] in that instead of a computer controlling an actuator that changes the shape/angle of a camshaft to alter the valves' motion, a computer controls a pneumatic actuator that acts directly on each valve. This allows Koenigsegg to precisely and quickly vary each individual valve's lift, duration, and timing. "Both the intake and exhaust valves can be opened and closed at any desired crankshaft angle and to any desired lift height," the company writes on its website.

Here are a few more photos of the Tiny Friendly Giant:

I must admit, my visit to Koenigsegg was too short, I was a bit too restricted on what I could photograph to provide you readers with the truly nerdy insight that I normally like to give, and I probably could have studied a bit more beforehand because some of the stuff went far over my head. But nonetheless, it was an incredible experience, and not a single Koenigsegg employee mentioned anything about me smelling like a fish. So that's a win.