Here's How The Mahindra Roxor Compares To A 1948 Willys CJ-2A Jeep Off-Road

I took the Indian side-by-side and my junky 1948 Willys off-road, and beat the crap out of both.

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

The Mahindra Roxor is the modern incarnation of the original civilian Jeep, the Willys CJ-2A. But to find out if it's as good in the rough stuff, I took the Indian side-by-side and my junky 1948 Willys off-road, and beat the crap out of both. After flooding the Willys' engine and denting the Mahindra's tub, one winner rose to the top. But by just a hair.

(Full disclosure: Mahindra lent me a Roxor and a trailer for a weekend, U-Haul let me borrow an Auto Transport trailer to bring my CJ-2A along for the ride, and Ram gave me a 1500 for a few days to tow the Willys. I borrowed a lot of stuff for this test, but I returned most of it without dents. Most of it.)

For decades, Wrangler and CJ enthusiasts have complained about how Jeeps aren't what they used to be. "Oh no, a plastic dash and interior creature comforts!" fans lamented when the YJ Wrangler launched for 1987. "Oh no, coil springs!" they cried in dismay when the TJ launched for 1997. "Good god, so much girth!" they groveled when the enormous JK debuted for 2007. "So many fancy electronics," they're probably complaining now that the new JL has shown up.

But now those "they don't make 'em like they used to" complainers have an opportunity to put their money where their mouths are, because Indian car company Mahindra—which got its start in cars by building Willys CJ-3Bs under license from Willys-Overland in the 1950s—does indeed "make 'em like they used to." In fact, I toured the company's factory and saw that it was actually building its Roxor in much the same way that Willys-Overland built its Jeeps in '40s.

The Roxor is—at least on paper—the real deal, as I pointed out in my article comparing the its tech to old Jeep CJs of yore. But to see if the Roxor was also the real deal off-road, I took it to Rocks And Valleys off-road park in Harrison, Michigan and put it head-to-head up against its distant relative.

Vehicle Dimensions And Geometry

At a time when four-door Wranglers on 40-inch tires seems to be becoming the norm, off-roaders tend to forget just how important size really is off-road, but it's one of the many things that makes old-school Jeeps so compelling as rough-and-tumble go-anywhere machines.

The Roxor is small, with its 148-inch overall length sitting over a foot and a half shorter than a new two-door Wrangler, and its narrow axles and body spanning a maximum of 62 inches—that's about 11 inches narrower than a Wrangler JL.

But whereas the Roxor is small, the Willys is tiny. At 123 inches, the little flat-fender is over two feet shorter than the Mahindra, and its 59-inch width means it can squeeze through a slightly narrower gap, too. Mine, with its slightly-taller-than-stock tires, and its aftermarket roll bar, also sits about five inches lower at roughly 70 inches in height, but without the roll bar and with the windshield folded, that disparity would be even bigger.

But one dimension that matters most off-road is the wheelbase. The Roxor's 96-inch span between its front and rear axles is 16 inches longer than that of the Willys, and—while that yields lots more interior space and probably helped with ride quality—it held the Roxor back when driving over steep crests.

Again, it's worth mentioning that the Willys CJ-2A's 31-inch tires are a bit taller than the roughtly 29.5-inch non-directional "NDTs" with which it came from the dealer, but the otherwise-stock flatfender managed to climb up and over grades without issue:

The Roxor, on the other hand, found itself beached a number of times:

In the photo above and the one below, the Mahindra's transfer-case skid plate rests against the top of the concrete ramp, preventing the vehicle from continuing over the same obstacle that the Willys climbed with ease.

This isn't a design flaw by any means, it's simply a compromise between interior space and breakover angle. The Roxor's got lots more interior room than the Willys thanks to its higher overall length, and to keep the approach and departure angles down, that means keeping the axles near the ends of the vehicle, stretching the wheelbase and decreasing thus lowering the breakover angle.

I will say that I don't feel that the compromise was worth it in the case of the Roxor. This is an off-road only side-by-side with no rear seats, so what's the point of all the extra room? Yes, you can fit coolers and tools and other equipment, but how much space do you really need for two people, and on top of that, there were no tie-downs in the back. Simple and cheap footman loops would have made that space much more usable.

Obviously, this compromise comes down to is the fact that the Roxor is based on the Indian-market Mahindra Thar. Completely changing the platform to lower the wheelbase for a low-volume vehicle like the Roxor wouldn't make sense, but the result is that the Roxor makes an off-road compromise for interior space that isn't all that necessary, and isn't all that useable. That is, until Mahindra offers a model with a family-style roll cage and a rear bench. Then I'll be fully onboard with the bigger tummy.

As for approach and departure angles, I haven't seen any official figures for the Roxor or the CJ-2A. Though the former's cousin, the Thar, has a 44 degree approach angle and a 27-degree departure angle. I'd venture to say the Roxor, with its minimalist bumpers, likely fares even better. This would put its figures close to what I've seen for the Willys's cousin, the World War II Jeep. In any case, during my off-road test, I never had any issues getting either vehicle's tires onto the obstacles.

As for the approximately 800-pound difference in curb weight between the lightweight Willys and the 3,000 pound Roxor, that didn't really present an issue, either. Perhaps the Roxor sank a bit deeper into the loose sand, but it still kicked butt up the loose inclines.

Articulation

My friends and I took both vehicles up Rocks And Valleys's 20 degree Ramp Travel Index—or RTI—Ramp to get an idea of how well both vehicles flex. The point, here, is to understand how much motion there is in the suspension, and thus how well each vehicle will can keep its tires planted firmly on uneven terrain.

A common metric used to compare articulation is Ramp Travel Index, which is simply the distance a vehicle can travel up a ramp while keeping all tires on the ground, divided by that vehicle's wheelbase and multiplied by 1,000.

The Mahindra Roxor made it up our ramp 39 inches. Divide that by the vehicle's 96 inch wheelbase and multiply by 1,000, and you arrive at a decent RTI score of 406. On the other hand, the 80-inch-wheelbase Willys, which made it 56 inches up the ramp before lifting one of its rear tires, managed an RTI score of 725.

That's a huge delta, and one that we could see off-road, as the Mahindra lifted tires where the Willys did not. Though admittedly, it wasn't apparent that this really held the Mahindra back that much on the particular trails we were tackling.

What's likely limiting the Roxor's suspension travel is its front sway bar, which is a great thing to have for dune driving or any sort of high-speed off-roading. It's an important safety device. But when crawling over rocks, ruts and other uneven terrain, having a way to quickly disconnect this anti-roll bar would have been nice, and likely would have increased the Roxor's wheel articulation dramatically.

Traction

Both the Roxor and the Willys have narrow solid axles with open differentials in the middle and all-terrain tires bolted to the ends. Neither was particularly great in slippery muck, with both vehicles getting stuck a number of times.

As you can see from the image above, the 235/70 R16 BF Goodrich all-terrains were not quite optimal in the nasty stuff. It really needed mud-terrain tires to get through this goo.

My Willys's 31x10.50 tires were bigger, but not any better, with the little Go-Devil motor spinning those tires seemingly endlessly:

There really was no major traction advantage for either vehicle.

Low End Torque And Gearing

I anticipated the Mahindra Roxor's 2.5-liter inline-four turbodiesel being a decent off-road mill, and it delivered in spades. It is a true gem.

The motor makes 62 horsepower and 144 lb-ft of torque, which is only two ponies and roughly 24 lb-ft more than the Willys's trusty Go-Devil motor. At least, assuming the Willys engine is in tip-top shape. But regardless, the Go-Devil is a great little torque-monster that, coupled with solid gearing, makes the CJ-2A one of the best stock off-road crawlers ever built. But the Mahindra actually seems a bit better.

From a gearing standpoint, both vehicles have similar crawl ratios. With its ridiculously short 5.38 axle ratio, combined with a 2.46:1 low-range gear and a 2.79:1 first gear ratio, the Willys's crawl ratio sits at about 37.

The Roxor has much taller 3.73 differentials, but nearly makes up for that with a 3.778:1 first gear ratio. Those two, combined with the same 2.46:1 low-range gear as the Willys yields a crawl ratio of about 35, just below that of the Willys.

But with its extra torque, smaller tires and especially its beautifully dialed-in drive-by-wire setup, crawling extremely slowly up an obstacle was markedly easier in the Mahindra. Whereas the line between "motion" and "stall" for the Willys was a thin one, I never once worried about stalling the Mahindra while slowly traversing steep grades.

Downhill was much of the same. I thought the Willys would be unbeatable by any vehicle that didn't have hill descent control, but in low range and first gear, the Mahindra felt even slower than the Willys. And in the off-road world, slow is good.

I can't say too much about the Mahindra's transmission, since I was in first or second gear most of the time. It's got long throws, just as the off-road gods intended, though I'll admit I sometimes confused which gear I was in every now and again. I also found myself slamming the shifter into the hand brake after jumping in and putting the vehicle in reverse. This seems like a silly oversight.

Robustness And Underbody Protection

We dented the Mahindra. My friends and I were driving down a rock, and the tub slammed into it, bending the tub slightly. The Willys also struggled while driving over this rock, making all sorts of unpleasant noises that—if it were possible to distinguish damage on a vehicle so tattered—might have also been body damage.

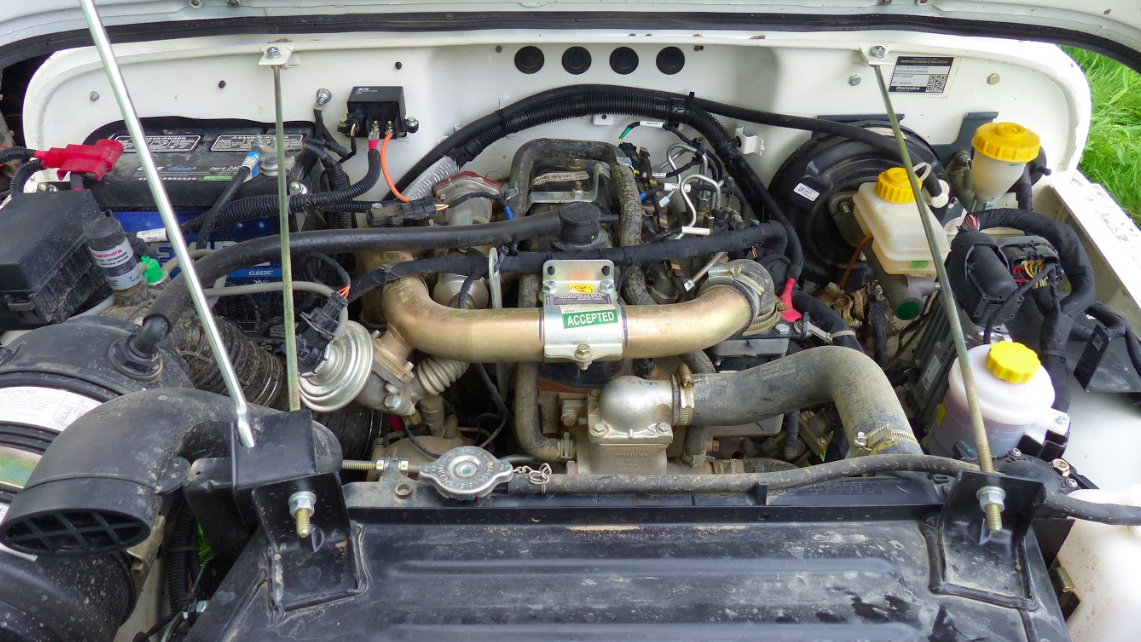

In any case, an off-road only vehicle with as big a belly as the Roxor should have rock rails. Moreover, unless the sheetmetal is quite thick, it should also have a skid plate under its oil pan like the Willys does:

But Mahindra told me it's working on protecting that oil pan, and the rest of the vehicle is fairly well protected. There's armor under the rear-mounted fuel tank, and there's this large transfer case skidplate:

There was really no clear winner in this department, and both vehicles took all the abuse we threw at them without any underbody damage.

Nimbleness And Comfort

Another area where the Roxor wasn't so great was on tight trails. For some reason, this thing's got the steering radius of a Great Lakes freighter. The Willys, with upsized tires restricting its steering, isn't much better, but it's also shorter. It seemed like I was making too many three-point turns in the Roxor, which was frustrating, because it's really not a large vehicle at all.

But the Roxor has a lot going for it. Like the Willys, its air intake is up high and its got drain plugs in the floor, but unlike the Willys, it's got some awesome modern comforts including power steering, power brakes and nicely cushioned seats.

This made driving the Mahindra 100 times more comfortable than the Willys, especially mine, whose seat cushion is literally a cheap pillow shoved into a trash bag.

Winner: Willys CJ-2A

In the end, the two were extremely closely matched. The Roxor's engine—combined with decent gearing—was excellent for controlling speed up technical obstacles, its approach and departure angles meant it could get tread on pretty much anything, its skid plating protected the important bits from damage, its power brakes and power steering made off-roading much more comfortable, and its available electric winch was a huge help in the mud and on the rocks.

But ultimately the win goes to the Willys, with simple geometry and suspension travel being the main factors. It's worth reiterating that the Willys's tires are about 1.5 inches larger in diameter and over four inches wider than what a stock CJ-2A would have come with.

But nonetheless, this Willys kept those tires on the ground more often, and it kept its belly off the ground more often. And that's what made it just that much more capable.