Germans Discover Military Jeep Hoods Used To Repair A Ceiling After World War II

Those hoods have just been discovered after over 70 years, and they carry with them some fascinating history.

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Like many other places in Germany, the western city of Bonn had plenty of rebuilding to do after World War II. So, with materials scarce, the owner of one building decided to use hoods from junked army Jeeps to build up his ceiling. Those hoods have just been discovered after over 70 years, and they carry with them some fascinating history.

The story about these army Jeep hoods comes to me via former German Air Force officer Paul Greve, whom I spoke with over the phone. He said that, some weeks back, one of his friends who lived near the building—a garage in Bonn that was being torn down to make way for another structure—had learned about metal panels discovered in the ceiling.

Thinking the panels could be from an aircraft, the friend contacted Greve, who's a member of the Luftkriegsgeschichte Rheinland, an organization comprised of air force history experts who work with scientific institutions to better understand and document war history, and especially to help find and identify airmen who went missing in action.

Greve, who says he's especially well-versed in 1915 to 1945 German air force history, arrived at the property, and—upon seeing the rust on the panels that bridged the garage's main beams—immediately knew these weren't airplane parts, since those are made of aluminum. These were Jeep hoods.

Speaking with the people who were tearing down the stable-turned-garage, Greve learned that the family has had the place for many years, and that the man who repaired the home in 1946 or 1947 had used junkyard parts to rebuild the ceiling after damage sustained in the war. This, Greve told me, was standard practice in post-war Germany—reusing as many available materials as possible, as cheaply as possible.

"Alle Häuser in diesem Gebiet sind durch das Bambardement zerstört geworden," he told me in German. Meaning, roughly, that pretty much all the homes near this particular building were blown up during the war. Just look at this video clip to see the state of Bonn in 1945—it's rough.

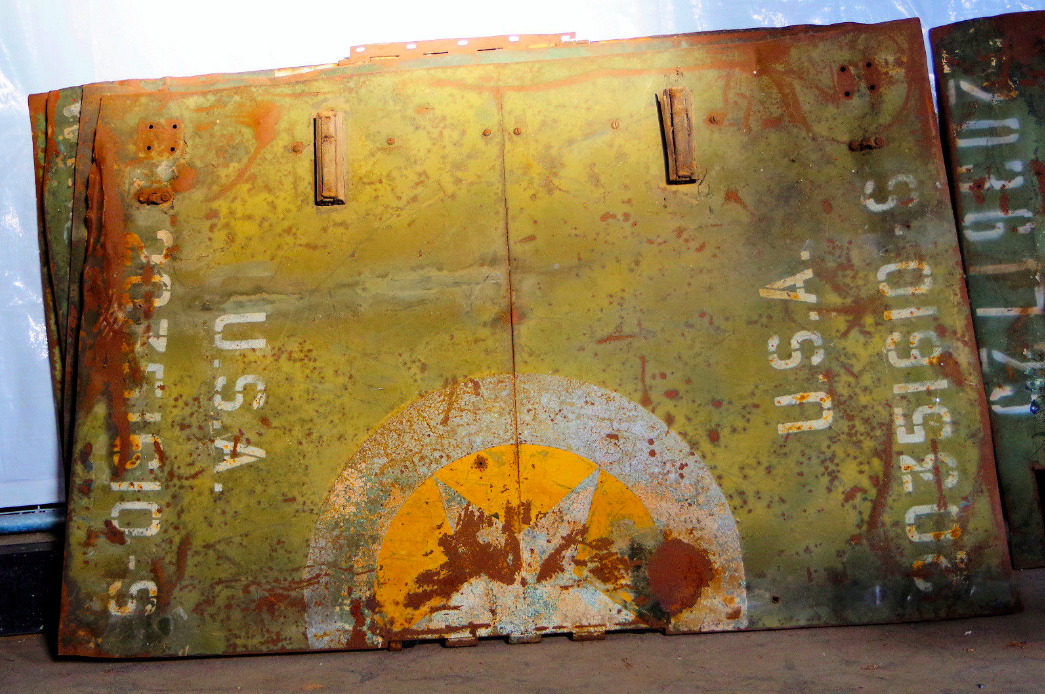

Greve pointed out the yellow paint on some of the hoods as reason to believe that these Jeeps may have been involved in the battle of Normandy. The special dye, brushed between the points of the invasion star on the hood, is called "M5 Liquid Vesicant Detection Paint," and its job—as I described in my article a few months back—was to change colors upon detecting dangerous chemical agents.

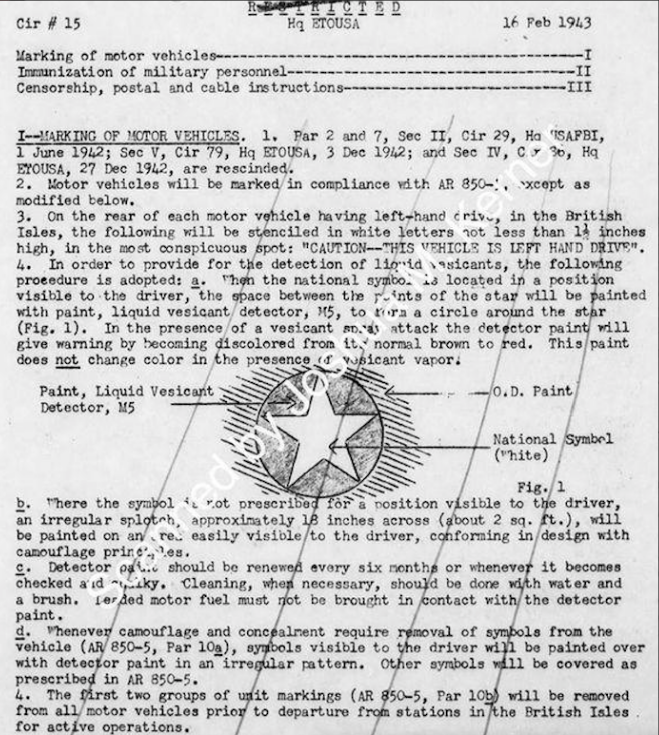

The U.S. army was worried that Germany might use chemical weapons on the battlefield, considering Germany did so during World War I. So, in 1943, the European Theater of Operations standardized vesicant paint, as shown in this "restricted" document found in the National Archives:

In addition, the paint was used on paper gas detection brassards that soldiers are said to have worn on their arms on D-Day.

To try to learn more about the hoods, I contacted Tom Wolboldt, a man who's well-known in the World War II Jeep community, in part, because he's undertaking the tedious task of sifting through tens of thousands of documents to learn exactly how the Willys MB and Ford GPW were built. He's building a huge database to help owners know what their Jeeps were meant to look like from the factory.

This service to the Jeep community and to Jeep history at large has been a multi-year undertaking, but it's solidified Wolboldt as one of the foremost experts on the vehicles. So when I asked him via his "Sequencing the Willys MB & Ford GPW Genome" Facebook page if he could help me learn what year the hoods were made based on their markings, it didn't take him long to answer.

The hood above, for example, is a Willys MB hood that—like all MB body parts—was built in Toledo. According to Wolboldt, the hood number most likely was used on a Jeep with a serial number in the range of 255500 to 256250, which means its date of delivery to the army was between Aug. 13 to Aug. 16, 1943.

Also, that "S" at the end of the hood registration number stands for "suppressed," meaning it was specially built with extra ground straps, capacitors, and other bits to prevent radio interference.

The hood above is actually that of a Ford GPW, Wolboldt told me. It was assembled in Louisville, Kentucky likely around September of 1942.

The hood registration number above also ends in "S" for "suppressed," and sits in the serial number range 259500 to 260250, meaning it was built on Aug. 28 or 29 of 1943. That's a big range of serial numbers for only two days, but Wolboldt says the factory in Toledo built over 300 MBs a day.

According to Wolboldt, the hood number 20234063 above is a Toledo-built Willys MB hood delivered on either Nov. 26 or Nov. 27, 1943.

The one above is also an MB hood from '43. Sitting in the serial number range 268500 to 269250, Wolboldt says it was accepted by the army on Sept. 27 or Sept. 28, 1943.

And the one above, with only half a vesicant paint-adorned star on it, is an MB delivered between July 7 and July 14, 1942. Speaking of vesicant paint, Wolboldt said it's not really possible to know the Jeeps' hoods' exact ports of entry into Europe after all these years, but the vesicant paint helps narrow down the location and the time frame during which they were used.

"I consider that they were prepared for combat in Europe since the troops could encounter gas at anytime," he told me over Facebook messenger. "As time went on the threat of gas became less. Vesicant paint was heavily used in '43 and '44 in NW Europe, Southern France, and Italy."

Between the date of deliveries gathered via the hood numbers, and the use of the vesicant paint, it's definitely possible that the Jeeps whose hoods used to make up this building's ceiling were in Normandy—which definitely adds to the pedigree of these flat metal panels. "Good chance most if not all went thru Normandy at some point in time," Woldboldt told me. "How many landed in the first wave? Most likely none."

According to Paul Greve, these Jeep hoods could have been used in the Battle of the Bulge, and they possibly also made their way to Feldflugplatz Odendorf, an old German air base roughly 16 miles from the heart of Bonn that the U.S. eventually took control of. Another possibility is that they were used to support the Battle of Remagen, which took place only 15 miles from the center of Bonn.

A lot of this, of course, is just speculation. But Greve is fairly certain, after talking to the folks tearing the building down, that the hoods wound up in a junkyard in Bonn-Endenich, where many broken military vehicles were stored about a third of a mile from the building in which the hoods—knocked completely flat—were discovered hidden behind wood boards.

One of those flattened hoods is for sale on eBay, with a price sitting at just below $600 as of this writing. It's not cheap, but these things are incredible pieces of World War II history hidden from sight for over 70 years.