How Special Paint On The Hood Of The World War II Jeep Protected Soldiers' Lives

The paint was there to keep soldiers safe. Here's how.

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

If you've ever seen a picture of a World War II Jeep with brown paint between the points of its "invasion star," you might have assumed it was just an aesthetic touch. But it was much more than that: the paint was there to keep soldiers safe. Here's how.

The paint's purpose was to protect against chemical weapons attacks. It's called "M5 liquid vesicant detector paint" (a vesicant is a chemical agent that causes blistering.)

After speaking with avid World War II re-enactor, retired U.S. Marine Corps tank mechanic and connoisseur of WWII Jeep canvases and also vesicant paint (he currently sells replicas of the stuff) Farrell Fox—I learned that this paint was actually standardized by the European Theater of Operations in 1943.

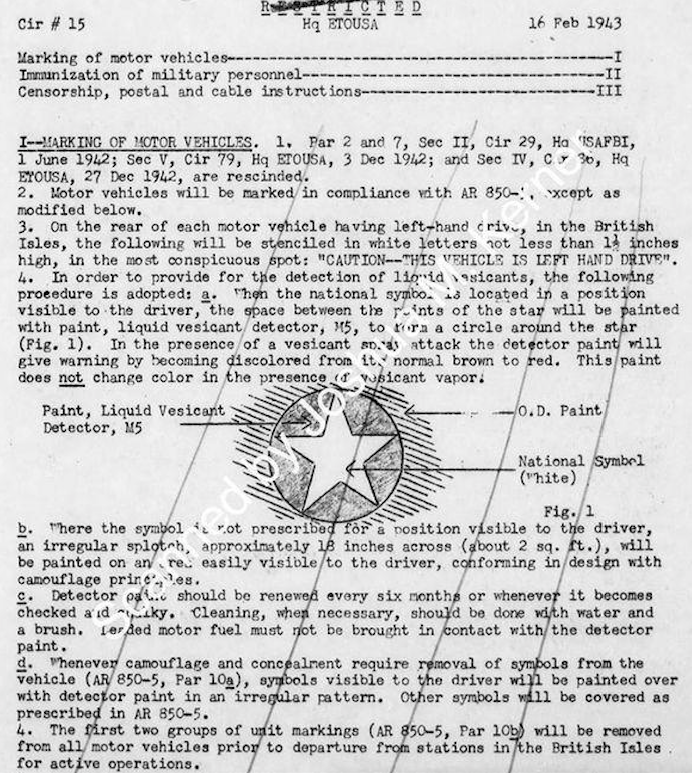

A "restricted" government document, which Fox told me he found in the National Archives, describes how the paint works, and how it should be applied to the five-point star (the star was the "National Symbol of all motor vehicles assigned to tactical units" per the War Department's 1942 document AR 805-5).

"In order to provide for the detection of liquid vesicants, the following procedure is adopted," the European Theater of Operations document reads. "When the national symbol is located in a position visible to the driver, the space between the points of the star will be painted with paint, liquid vesicant detector, M5, to form a circle around the star."

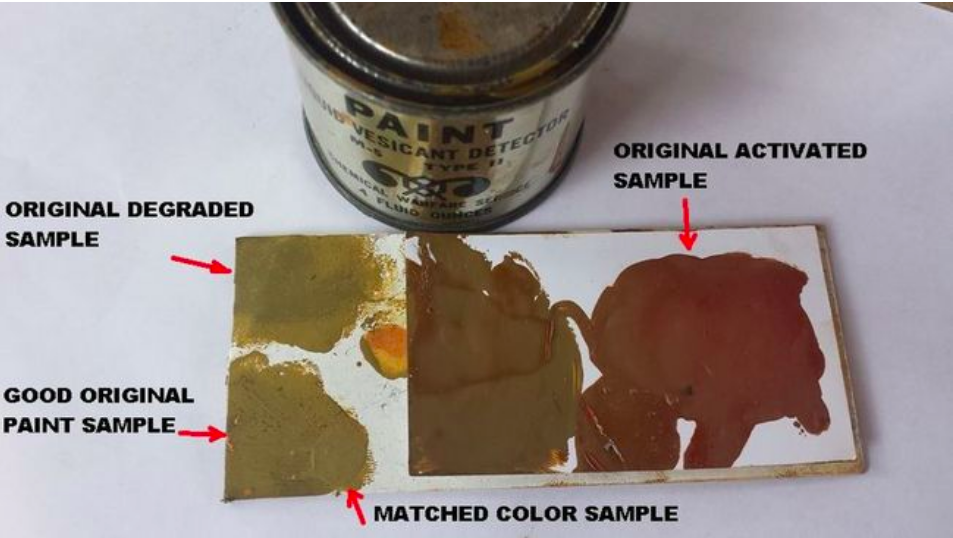

"In the presence of a vesicant spray attack," the document continues, "the detector paint will give warning by becoming discolored from its normal brown to red," going on to say that the paint does not work if the vesicant is a vapor.

The document continues, saying that if the star symbol isn't visible, a two-square foot blotch of paint should be painted on an area that the driver can see, and that the paint has to be renewed twice a year or "whenever it becomes checked and chalky." The paint should be cleaned with a brush and water, and it should be kept away from leaded fuel, the document states.

It's no surprise that this paint was meant for the European theater, as Germany had become well-known for its chemical weapons use during World War I.

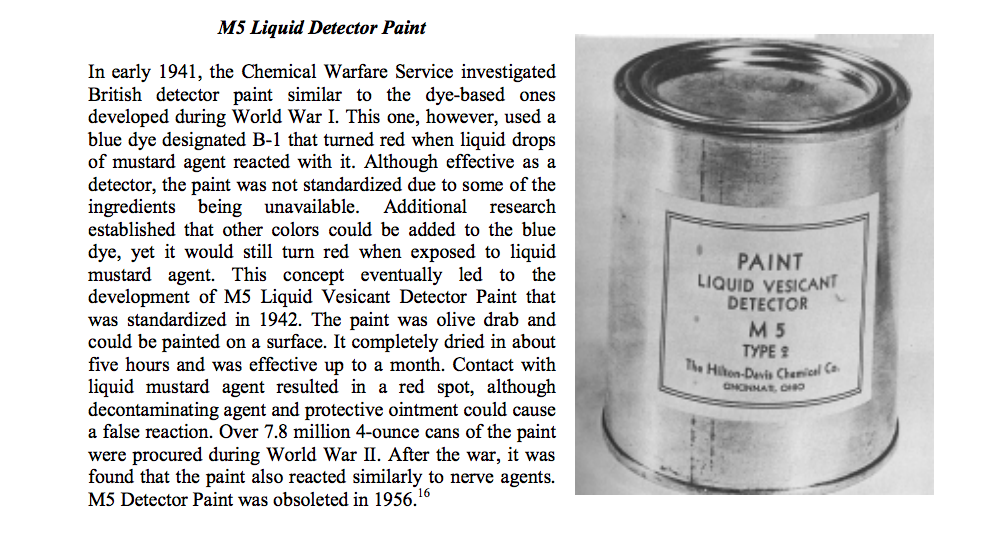

In fact, according to a paper written by the U.S. Army Soldier and Biological Chemical Command, American researchers during World War I developed a paint out of linseed oil paint and a "du Pont lacquer/linseed oil enamel paint," copying the Germans, who were painting their mustard shells to detect leaks.

(At the same time, it's unlikely that the paint actually helped save any lives during the Second World War, as the Nazis are known to have used chemical weapons primarily in concentration camps, and not battlefields. Still, given the extensive use of gas during the previous war by the Germans, it makes sense that it would have been seen as a necessary and practical precaution.)

According to the document, the prototype paint turned from yellow to red within four seconds of contacting a mustard agent, but the research was never finished.

The report goes on, saying that after looking at blue British detector paint in the early 1940s, the U.S. army came up with olive drab M5 Liquid Vesicant Detector Paint (it's worth noting that a number of sources say the paint was more of a yellowish-brown color), with 7.8 million four-ounce cans making their way to the U.S. military by the end of World War II (here's one original can for sale on Ebay).

The paint was brushed onto various surfaces, and dried within five hours. After that, for the next month, the paint would turn red when met with a liquid mustard agent. (Note that this conflicts with the European Theater document, which says the detector paint generally works for six months).

Some sources online state that the paint is effective at detecting not just mustard gas (which, it's worth noting, isn't actually dispersed as a gas but rather as liquid droplets), but also Lewisite vesicant and even nerve agents.

Using paint to detect such chemicals is crucial, as—according to the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons—agents like mustard gas, which have a characteristic odor, tend to dull a victim's sense of smell "after only a few breaths so that the smell can no longer be distinguished." In addition, the implementing body of the Chemical Weapons Convention states, respiratory damage can occur in the presence of even tiny, unsmellable concentrations of the agent.

So the paint is there to provide soldiers with a detection method other than smell, which is important, because the effects of mustard gas are devastating, with Lifehacker describing them in an article, writing:

Once exposed, victims smell an odor similar to mustard plants, garlic, or horseradish. Soon, they begin to feel intense itching and skin irritation over the next 24 hours. Gradually, those irritated areas become a chemical burn and victims develop blisters filled with a yellow fluid (here's the least graphic photo I could find). These burns can range anywhere from first-degree burns to deadly third-degree burns. If one's eyes are exposed during an attack, blindness is also a possibility.

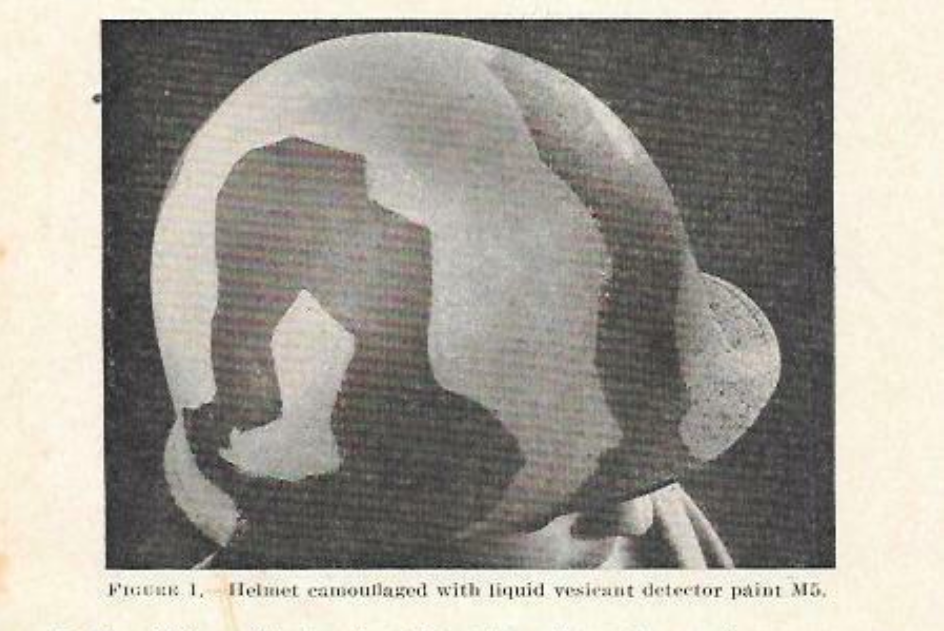

It's obviously critical for soldiers to be able to recognize the presence of this nasty stuff, which is why the U.S. military used this M5 vesicant detection paint not just on vehicles (more than just Jeeps; thats a Chevy K43 truck hood in the photo above), but also on helmets and on "gas detection brassards," which Allied soldiers wore on their arms as they invaded Normandy.