For the 2022 Formula One season, the Mercedes-AMG Petronas F1 Team will race in a traditional silver livery after two seasons of entering black-liveried cars. The silver racing cars of Mercedes-Benz have been synonymous with success in Grand Prix racing for 99 years. Every tradition has an origin, and this origin has been thoroughly mythologized.

Before sponsorship was deregulated in the late 1960s, the Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile (motorsport’s global governing body) required competitors to enter international events with cars painted primarily in a prescribed color based on the country a competitor represented. The national color selected by Germany was silver, to explain the connection as briefly as possible.

Though, it only gets more complicated from there. The practice of mandating national colors began with the Gordon Bennett Cup in 1900, a proto-world championship race. When the Automobile Club de France ended the Cup and replaced it with the inaugural Grand Prix, it solidified most of the colors we remember today. Though, German cars were run in white. The current Mercedes F1 team made a nod to this fact in its part-homage livery at the 2019 German Grand Prix.

The point of contention is when white became silver at some point in the early 1930s.

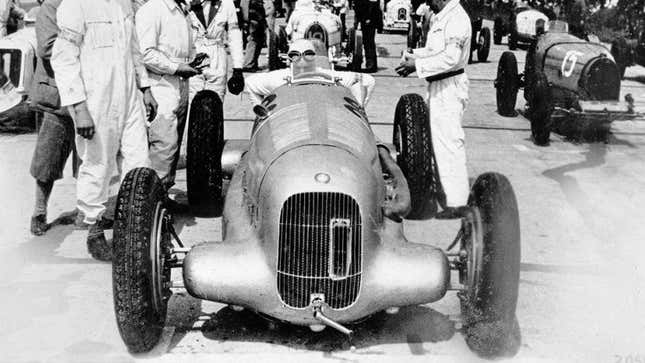

The widely-circulated story is that the Mercedes-Benz team arrived at the 1934 Eifelrennen at the Nürburgring with its new Mercedes W25. According to team principal Alfred Neubauer, the team’s three W25s were overweight. The Grand Prix regulations for the 1934 season prescribed a maximum weight limit of 1653 pounds. (750 kilograms) Neubauer and one of his drivers, Manfred von Brauchitsch, came up with the novel idea of stripping the white paint off the bodywork to make weight, and the Silver Arrows were born.

Von Brauchitsch would win the Eifelrennen in the gleaming aluminum-clad W25’s debut race.

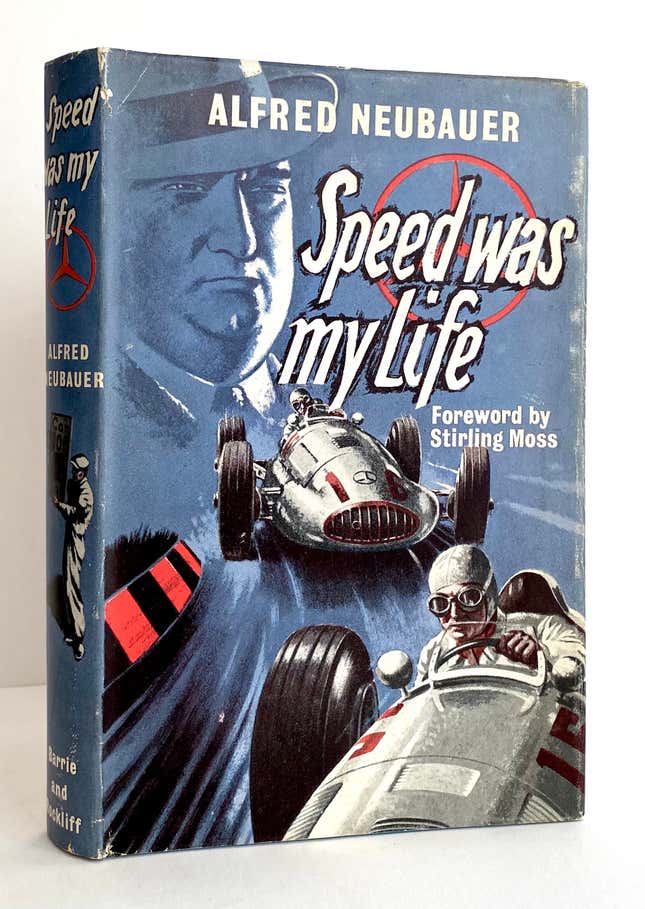

The story is literally to good to be true. Several embellishments and omissions made the narrative more evocative because Alfred Neubauer crafted it this way for his memoir Speed Was My Life. The memoir was first published in 1958, years after Mercedes-Benz withdrew from motorsport in the wake of the 1955 Le Mans disaster and Neubauer retired. This was the first time the general public learned of the stripped white paint story.

Yes, Manfred von Brauchitsch did win the 1934 Eifelrennen in the W25’s debut race. Though, there are some holes in the stripped paint story.

First, Mercedes-Benz wasn’t the only team to enter silver cars that day at the Nürburgring. Their rival Auto Union also entered three silver mid-engine Type As.

Second, both teams appeared at the Avusrennen in Berlin the week prior. Mercedes-Benz took part in practice but didn’t enter the race. There isn’t any definitive photographic evidence of what the W25s looked like that day. Though, the Auto Union Type As are silver in photos of the event.

Third, the Eifelrennen and the Avusrennen were not run to Grand Prix regulations. Race officials didn’t enforce a maximum weight limit at either event.

The true origin of the Silver Arrows predates the 1934 season. However, this story still includes racing driver Manfred von Brauchitsch.

In 1932, Mercedes-Benz didn’t have a factory racing team. The company had shuttered the program citing the terrible economic conditions created by the Great Depression. While there were no German automakers in racing, the country was not short of elite drivers. These drivers had to secure their own ways to continue racing.

Manfred von Brauchitsch contested the season with a Mercedes SSKL owned by his cousin Hans von Zimmermann. He also received financial support from invested patron Alfred Neubauer. Without factory backing, extreme measures were taken to keep his cousin’s SSKL in the same league as front-line Grand Prix machinery. A streamlined bare aluminum body designed by Reinhard von Koenig-Fachsenfeld was mounted to the Mercedes SSKL.

Future three-time European Champion and Mercedes teammate Rudolf Caracciola secured a deal with Alfa Romeo. Caracciola wasn’t on the Alfa factory team but got access to the Italian manufacturer’s cars as a privateer, painted in German white.

Von Brauchitsch and Caracciola went head-to-head that season at the Avusrennen. The thrilling contest on the Berlin highway circuit went down to the final lap. The Mercedes driver overtook the white Alfa Romeo for the lead on the penultimate straight of the race. The modified SSKL had an advantage on the AVUS’ lengthy straights at it could reach speeds of 142 mph.

The race was notable for another reason. The 1932 Avusrennen was one of the first races broadcast on radio. While the car was described by spectators as ugly and similar looking to a pickle, it was called a Silver Arrow on the radio broadcast. The exciting finish certainly captured the imagination of anyone who listened in and unintentionally tied Mercedes and Germany to the silver livery.

This race would also be the highlight that convinced Alfred Neubauer to sign Manfred von Brauchitsch onto the reformed Mercedes-Benz racing team in 1934. To be honest, it’s understandable that Neubauer would want to attach himself and Mercedes proper to one of the most iconic moments in recent German motorsport history. Though, it seems strange that Mercedes kept the charade alive for so long.

Neubauer was the first team principal of a factory racing program. He had an eye for talent and a flair for the dramatic. Neubauer led the team through its successes in the 1930s and 1950s while knowing how to play to the crowd and race officials. At the conclusion of the 1955 season, he sobbed while tossing a sheet over on his cars, ceremonially lowering the curtain on Mercedes’ time in racing and his career. Current Mercedes team principal Toto Wolff carries himself on race weekends similarly to Alfred Neubauer.