Every day, tens of thousands of flights take to the sky, ferrying a couple of million people to their destinations safely. If you’re one of the lucky passengers to get a window seat, chances are you’ve probably spent some time staring out the window, looking at the plane and the world before. If you’ve looked at the wings long enough, you’ve probably seen a bunch of metal rods jutting out into the sky. What are those for? They’re actually an important safety element.

As an aircraft flies through the sky, the friction of air flowing over the aircraft’s skin causes the aircraft to build up static electricity, Aviation Consumer notes. You can also get a static charge in storms, clouds and yes, lightning strikes.

Qantas Airlines says that statistically, an aircraft gets hit by lightning on average once a year. When that static electricity discharges, it can cause radio frequency interference or cause communication and navigation radios to lose reception. In extreme cases, the discharge can cause damage to equipment or possibly a spark. Thankfully, the aviation industry had figured out a solution long ago: the static discharge wick.

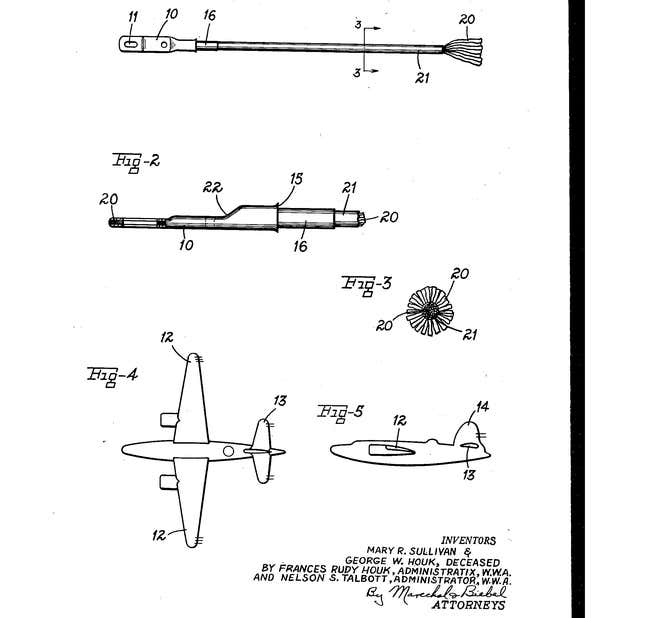

The static discharge wick — often just called the static wick today — was invented in the 1940s. Back then, TWA used a 1937 Lockheed Electra Junior as a testbed to develop technology to bleed static discharge off of an aircraft, the Platte County Citizen reports. Florida-based Dayton-Granger is often cited as the inventor of the static wick, creating them in the 1940s before getting a patent on them in 1950.

They’re small, but they do a lot of work.

Static electricity buildup flowing through an aircraft is more likely to pool up around thin, sharp edges of the airframe. That’s going to be the ends of the ailerons, flaps, winglets and even parts of the tail.

A static wick consists of bundles of carbon fiber wrapped up into a cylinder and extending up to about eight inches from the trailing edges. These fibers extend out to a sharp point and a number of static wicks get riveted to the trailing edges of the aircraft.

The wicks provide a path for the electrons to leave the aircraft safely without causing damage or disruption.

They do enough a good job that they can expel the charge from a lightning strike, too. And when they get damaged from something like a lightning strike, they can be replaced.

SRI International, a manufacturer that began making static wicks in the 1950s, notes that before static wicks planes would also sometimes experience what’s known as St. Elmo’s Fire, or a bright blue light glowing from a buildup of static electricity. Today, that, along with the other dangers of static electricity, are much rarer thanks to static wicks.

So the next time you board a plane, you have yet another thing you can point to that has helped make flying as safe as it is today. Go ahead, use this information to annoy the person sitting in the center seat.