This is the first story in a series of stories on the history of gasoline. So far, Jalopnik’s tech coverage has been focused primarily on the emergence, or reemergence of the electric vehicle. One of the primary arguments levied against electric cars and electric charging infrastructure has been that bringing both into the mainstream would take significant investment from private and public actors, and that this has not generally been politically palatable in the United States.

In this ten part series, award-winning journalist Jamie Kitman will lay out how American corporate and government entities have been cooperating on a vastly more costly, complex and deadly energy project for well over a century: gasoline.

July 4, 1976. I remember wondering whether my maternal grandfather Irving Sibushnick would have ever bothered striking out alone from his Besarabian shtetl as a boy of 14— bound for the new world — if he’d known that, seven decades on, his only grandson would be marking the American nation’s gala celebration of the bicentennial anniversary of its Declaration of Independence by pumping gasoline at a filling station on Route 46 East, in Fort Lee, New Jersey.

But there I was. Sweating profusely in black coveralls with the proud logo of the Merit company – a regional, off-brand gasoline discounter – sewn to my breast pocket. In exchange for $2 an hour, I’d spend the summer asking people whether they’d prefer regular or premium gasoline, known as high-test. Then I’d proceed to fill their tanks as directed.

“Two high?” I inquired of a couple of youthful longhairs in an ancient, hump-backed Volvo 544 one day. I only meant to confirm their mumbled order, which I’d taken to mean two dollars of Merit’s finest premium. But they collapsed into fits of laughter. Only then did I work out that they were indeed “too high.” As, I’d been learning, were many of my co-workers. One of them, the ne’er-do-well alcoholic dad of a distant high school acquaintance, slept outdoors behind the station most nights. That same summer, though not the most devoted fan, I caught up with Frank Zappa’s cautionary chestnut, “Wind Up Working in a Gas Station.” Pumping gas was clearly a line of work one hoped to avoid.

Though it was the socio-economic dimensions of such employment which alarmed me at the time – as near as I could tell, in life, the gas station attendant rarely got the girl — there were ample health grounds for considering other career opportunities. But, to be honest, these concerned me not at all.

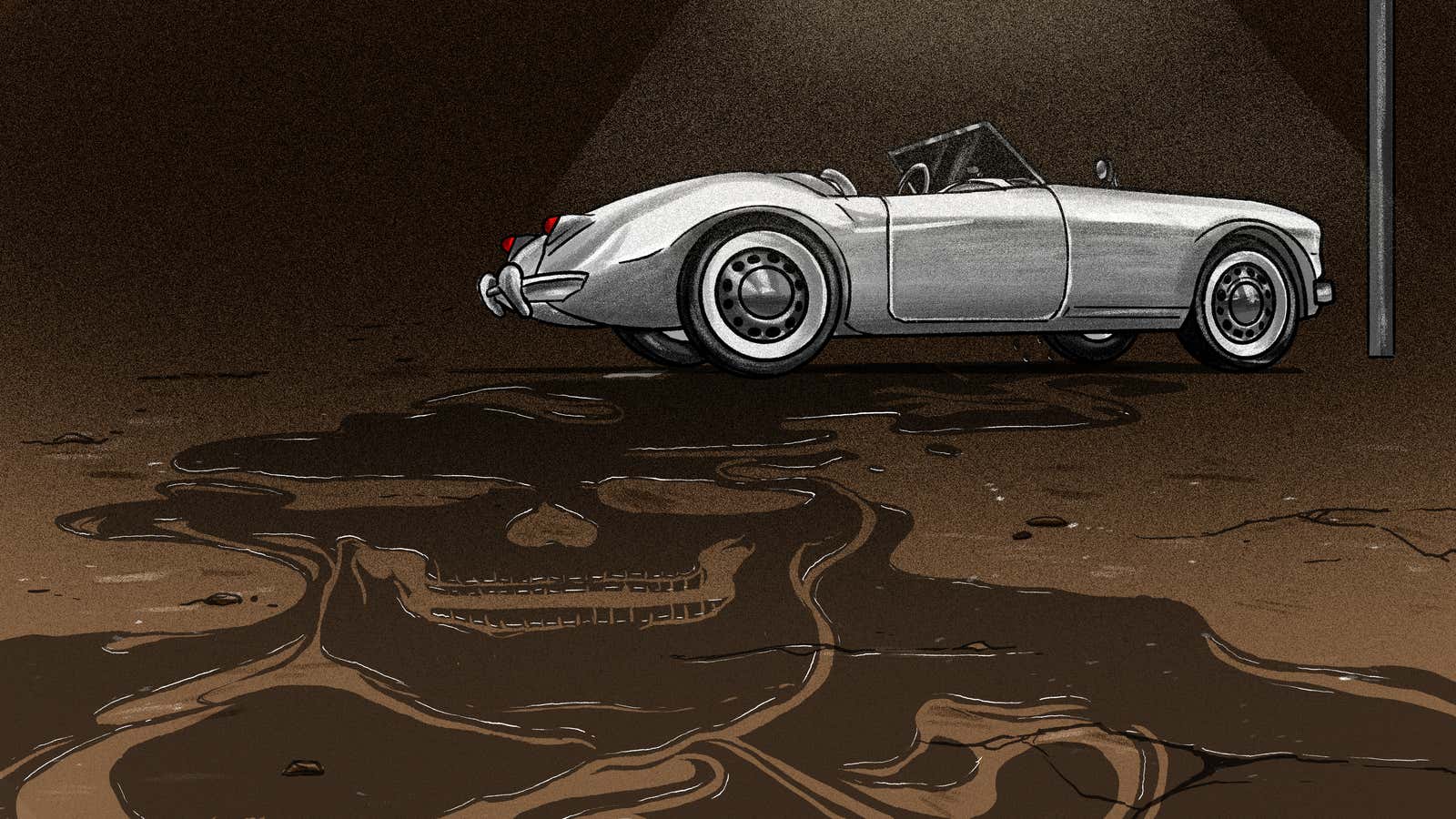

Gasoline was poison, if you’d asked me I would have told you that, but I’d grown up around it and kind of like the way it smelled. I was against air pollution, but I liked cars more than just about anything and, much to my parents’ bewilderment, worked on them in my spare time. Often as not on these occasions, I’d wash dirty car parts in gasoline, with my bare hands. Like the older kids who showed me how, after cleaning the parts, I’d spill the oil- and grit-contaminated gasoline down the nearest garage toilet or outdoor sewer when the cleaning was done. Sometimes, we’d siphon gasoline out of tanks, using a length of hose, and wind up with stinging mouthfuls of gasoline, quickly spit out. Such was the state of environmental and toxicological awareness in my little town, two and a half miles from New York City, in the late 1970s/early 1980s. One time I even wound up in the hospital for five days when I became gravely ill after spending an afternoon washing MGA parts in leaded gas. I didn’t even mention what I’d been doing and they never did figure out what was wrong with me.

A few years prior to my arrival at the Merit forecourt, they’d started selling a new kind of gasoline. It was called “unleaded” and, frankly, I was unimpressed. Why on earth would they take the lead out of gasoline? If God hadn’t intended for lead to be in gasoline, why’d he put it there in the first place? As an idealistic teen born into the civil rights and anti-war movements, and as a supporter of clean air, clean water and the newly-created Environmental Protection Agency, you’d have thought, looking back, that I would have felt otherwise.

But even though I read the newspapers and viewed the public posturing of corporations with suspicion, I didn’t really understand the benefit of this unleaded stuff at all, except that it had something to do with these new-fangled air-pollution control contraptions called catalytic converters that were being installed as part of the exhaust systems of some new automobiles. Leaded gasoline apparently destroyed the catalysts almost immediately, even after only one or two tankfuls.

So you pretty much had to use unleaded gasoline if you owned most of the new cars being built in the 1970s. But for me, an impoverished teenager with parents who didn’t subscribe to the popular suburban practice of buying their kids cars, a new automobile was out of the question.

But, for reasons that remain unclear given my city-born and largely car-indifferent parents, I’d been auto-obsessed from an early age. My folks recall that my first word was “Volksendriven,” which is not actually a word but what I called a passing VW Beetle at the age of 14 months. As a child, I remember attending my cousin Bill’s Bar Mitzvah in Brooklyn and being dragged into the street to identify passing cars. “1957 Desoto, 1964 Dodge Dart GT,” I would squeak to the amazement of the older boys and blue-haired grandmothers. But as I tell my own children, I wasn’t an idiot savant, just an idiot. Despite my parents’ lack of financial assistance and their crushing lack of enthusiasm, when I was a teenager I made it my business to own my own car.

Unfazed by parental hostility to the idea and their antipathy to my taste in cars, undaunted by the fact that I didn’t even have a driver’s license, I took $250, a princely sum representing my entire life savings, and purchased an MG “A” roadster. I was 16. A decidedly un-cherry example of the famous British two-seater, in the model’s 1962 run-out 1600 Mk.II form, my MG looked bad, it ran bad and it leaked like a sieve when it rained. Naturally, I loved it.

I was, therefore, deeply alarmed by a rising crescendo of ominous pronouncements in the media (especially in the pages of the car magazines I devoured every month) that unleaded gasoline would destroy old cars and their engines – which, we’d been told, needed lead — in short order. Eventually, I gathered, it was the goal in some quarters of the U.S. government to outlaw leaded gasoline entirely. Not only would old cars like mine and the many I daydreamed about owning in the future be destroyed or rendered useless, but, in this dreaded, unleaded world, new cars would forevermore be stripped of their performance. For all the get-up-and-go that would be left, establishing the gearhead’s favorite yardstick of automotive performance – the time elapsed in the crucial zero-to-sixty sprint –would no longer require the use of a stopwatch. A sundial would suffice.

While I fretted nervously along with the rest of America’s enthusiast population, lead was, as a nation gearheads had dreaded, gradually phased out from most gasoline sold in America. In the years leading up to its final departure, I spent countless hours tracking down stations that still stocked the “good stuff” so as to fuel the procession of old MGs, Triumphs and Volvos that had begun to pass through my life, convinced along with millions of Americans that they would meet their makers without lead. When leaded gasoline disappeared entirely from the forecourts, I took to buying lead additive in a can, which I’d carefully drain into each tankful to protect my beloved machinery.

Then, one day, I inadvertently misplaced my can of lead additive. Late for an appointment, I drove for the first time with straight unleaded gasoline in my tank. I listened carefully for untoward noises and waited for disaster to strike, but nothing happened. Still, I promised myself, I’d add some later. But somehow, caught up in events, I forgot. By the next time the MG’s erratic fuel gauge was reading empty, I’d managed to forget again and again and run through five tankfuls of unleaded, with no apparent ill effects. As an experiment and a useful economy measure, I stopped buying the lead additive entirely and then completely forgot about it. Ten thousand miles later, when I sold my MGA (and bought a 1969 Lotus Elan S4, with funds temporarily diverted from my law school tuition,) it occurred to me I’d experienced no ill effects from the lack of lead whatsoever. I filed this information away with relief and some puzzlement. Car enthusiasm might continue unabated, even in a lead-free world.

In the late 1980s, after finishing law school, I began writing for car magazines like the ones I’d read since childhood. The furor over leaded and unleaded gasoline had largely subsided, none of the dire prophesies having come to fruition. New cars were faster than ever and old cars ran fine on the unleaded gasoline being sold. Though the air was still polluted, the contribution of any individual new automobile would become more than 90% smaller than it once would have been, thanks to catalytic converters. I didn’t make too much of it, though the more I studied the automobile and petroleum industries and their histories of reckless activity and studied inaction with regard to pollution and the common weal, the less inclined I felt to take their word as final.

I loved cars as much as ever. But like anyone impressed by scientific fact and scholarly opinion, I couldn’t help feeling concerned about the automobile’s undoubted contribution to the world’s air pollution problem. I had also long been concerned with the subject of automobile safety. Measured against the standard of most other automotive journalists, who typically identify their interests with those claimed by the industry they cover, which has historically opposed pollution and safety legislation with vigor, these beliefs back then placed me squarely in the lunatic fringe.

When I wrote the very first op-ed piece decrying the growing popularity of unsafe, ecologically unfriendly, sport utility vehicles for the New York Times in 1994, I irked some of my magazine editors and was crossed off the Christmas card list of more than one prominent automaker. Yet, at the same time, my continued interest in – and growing collection of — old cars lent me a sort of credibility, grudgingly conceded. I was what they call in the industry “a car guy” – someone who actually liked cars (sadly, not a given in the car business,) rather than some chicken-little environmentalist who didn’t know the difference between a Hemi and a semi.

Thus I was peculiarly well-situated to smell a rat in the late Nineties when I began reading about a furor brewing in the United Kingdom over an European Union directive mandating the removal of lead from gasoline (or petrol as the British know it) in the year 2000. Strangely, the same desperate claims to save lead were being resurrected. Makers of the lead additive were placing alarmist full-page ads in newspapers, filled with the same untruths that had terrified me as a boy twenty years earlier. Government ministers and MPs were up in arms, citing these very falsehoods, some going so far as to urge withdrawal from the European community. Even the traditionally staid Rolls Royce Owners Club were moved to march (actually, drive) on the Houses of Parliament in protest.

How could this be? We’d had the same discussion in America two decades previous, as well as the benefit of the intervening years to learn the truth: the removal of lead from gasoline had hurt no one – other than the makers of the additive – and helped everyone, with American blood lead levels falling an average of 90 percent. It was, if anything, one of the great public health triumphs of the modern world and had been almost entirely painless. Was no one paying attention? Had our information society somehow failed to transmit this vital data tidbit across the pond? Was there no one in all of Europe to correct them?

Didn’t they have a phone? Were there, perhaps, larger forces of disinformation in motion?

What would become an ongoing part of the rest of my life’s work became clear, as I sought find out the real truth about lead in gasoline. The first result of my study, “The Secret History of Lead,” appeared in The Nation magazine in 2000, and made the case that some of America’s biggest corporations – DuPont, its longtime charge General Motors, and Standard Oil of New Jersey (today known as ExxonMobil,) – had put lead in gasoline for profit in the 1920s, ignored legitimate health warnings and covered up safer alternatives, which we use today. Translated into 16 languages and a mini-best-seller in France, it remains a piece of history its star players would prefer we forgot.

I accused the companies of wildly overstating the benefits of the additive and monopolizing all scientific research in the area for forty years, to grossly understate lead’s hazards, to life and property. I called the companies some of the biggest polluters of the 20th century and the prime architects of that century’s lasting contribution to the art of pollution – the scientific uncertainty principle. (“You say ‘It’s dangerous,’ we say ‘We’re not sure,’ so let’s study it for forty years and make lots of money before washing our hands of the whole thing.”) Finally, I recounted how, faced with a declining market in America and other western countries, the lead gasoline industry had stepped up efforts to sell their product in the Third World, where they continue to sell it today.

Serious charges, to be sure. Yet when a reporter for the Richmond Dispatch contacted each of the major players for a response, General Motors declined comment, ExxonMobil didn’t return phone calls and duPont said it stood behind its “200 years of service to the American public.” A spokeswoman for Ethyl– the company founded by these three companies to market leaded gasoline in the 1920s — did respond. She accused me of “using 20/20 hindsight.” As an assessment of one’s research, it was flattering, though I wondered whether she hadn’t meant 20/340 hindsight. Doesn’t 20/20 hindsight imply, that one’s analysis was not just broadly accurate, but boasted perfect clarity? Perhaps it was only in retrospect that Ethyl could appreciate the fact that they’d blanketed the world in lead dust, and then spent more than eighty years lying about it.

The Nation piece won the IRE medal for investigative magazine reporting in 2001, a great honor, but the story about the multi-billion dollar sham foisted upon the world – in a realm that touches the life of every person on the planet, because the world is, thanks to a small group of well-known businessmen, covered in lead dust - is still barely known (it also has yet to be reported by a single American daily newspaper of consequence.) Knowing that it might alienate me further from some of the people I work with, I figured to write about it one more time, but this time with much I’ve found out since – about the lead adventurers, but also about the composition of gasoline since the lead came out and the story of oil industry that chose to put it in. Maybe it will help us remember the time we trusted ExxonMobil and DuPont and the others with our health and well-being and what happened when we did. Then again, maybe not.

Either way, it will have beat working in a gas station.