In the modern era of motorsport, race performance is all about telemetry—or, a method of data collection that can be analyzed to understand even the most minute nuance of the race car. But it can be a little confusing to understand if you’re just looking at a big ol’ chart of numbers and graphs. Today, we’re going to run down the ins and outs of telemetry as it’s used in Formula One, one of motorsports most technical series.

(Welcome to Motorsport Explained, the series where we break down racing rules and concepts in easily digestible ways for all the beginners out there. If there’s something you’ve always wondered about or something that has never made sense, leave your topic in the comments or email me at eblackstock [at] jalopnik [dot] com.)

Telemetry In A Nutshell

Telemetry is basically one of the reasons why F1 is so damn technical these days. In 1978, Ken Tyrrell hired American physicist Dr. Karl Kempf to rig the team’s cars up to a bunch of sensors and recorded as much data as possible: speed, suspension movements, directional forces, throttle, braking, and more.

Kempf pioneered tape-recording telemetry method over at Goodyear, and he brought it to F1, according to a New Scientist article from 1978. He also “plans to put a microprocessor in the car as soon as he can solve the extreme problems of electrical noise and vibration.”

Basically, though, those cassette tapes enabled Tyrrell to wring tons of data out of the car that other teams just didn’t have access to. If you can understand, from a hard scientific perspective, how your car is performing, you can optimize it in a way that just isn’t possible for a human. A sensitive engineer could do a damn good job setting up a car, but as we’ve learned in recent years, performance can come down to the smallest changes.

As technology evolved and grew more sophisticated, so did telemetry. Computer systems could interpret data without having to go through a lengthy period of human translation first, so data could be more accurate. Computers and sensors also got a hell of a lot smaller, so you could stick ‘em in a ton of different places.

Telemetry tells you tons of info about both the car and the driver. You can figure out why, say, Valtteri Bottas is slower than Lewis Hamilton based on how he drives the car. You can figure out why your chronic braking problem never seems to get any better. When it was introduced to racing, it revolutionized the sport and contributed to the exponential development of racing tech that we’ve seen throughout recent years—and it’s also part of why F1 has hit a bit of a plateau. When you’ve basically perfected a machine, how are you supposed to keep improving it?

Telemetry isn’t totally faultless, and you can’t rely on it to make every single change in a race car. When drivers get behind the wheel, there’s an undoubtedly human element to the function of a vehicle. Different drivers have different preferences when it comes to how a car is set up. So, while an engineer can tell you that your rear wing needs a different setup but you feel like it’s perfect, that’s not something the technology can rationalize away.

How To Collect Telemetry

Nowadays, there are over 120 different sensors scattered throughout the car that monitor its performance. Those sensors collect data at a rate of over 10 MB per second. That data is beamed into the garage via antennae in the front of the car, and from there it can be sent back to a team’s headquarters for further analysis—something that’s especially crucial during the COVID-19 era, when track personnel are limited. That data can also be shown on a driver’s steering wheel, helping that driver make decisions of their own.

You can watch a side-by-side display of an F1 car running a lap and the telemetry that shows up at the same time below, courtesy of Sauber:

After a race, teams have collected at least 30 GB of data. That’s the equivalent of 6,900 mp3 music files, 480 hours of music, about 1000 photos, or about 40 hours of movies.

While some pieces of information are sent via antenna, others are collected when an engineer plugs the car into a laptop.

What To Monitor

At this point, there really isn’t anything that you can’t monitor when it comes to collecting telemetry. If a part of the car does a thing, that thing can be quantified with data, then analyzed to perfect it.

There’s a really comprehensive list at Fi.com, but these are some of the basics:

- Speed of the car

- Wheel speed for each wheel

- Understeer and oversteer

- Steering angle

- Acceleration

- Braking, both front and back

- Gear selection

- Brake Balance

- Engine revs

- Tire pressure for each tire, including puncture warnings

- Whether or not DRS is enabled

- Engine mode

- Torque

- Fuel

- Delta to the last lap

- Centrifugal forces

- Clutch position

- Downforce

- Hydraulic pressure

- Oil pressure

- Engine temperature

- Transmission

- Exhaust

As you can tell: basically everything. During a race, these measurements help teams plan pit stops and craft strategy—if your tire wear isn’t bad, for example, you can go ahead and send it for those last few laps as opposed to your opponent, who now has to nurse his rubber to the finish. It’s helpful during practice sessions to predict how both qualifying and the race will go. And it’s especially helpful during pre-season testing to make sure the physical car is doing what you expected it to.

How To Interpret What You’re Seeing

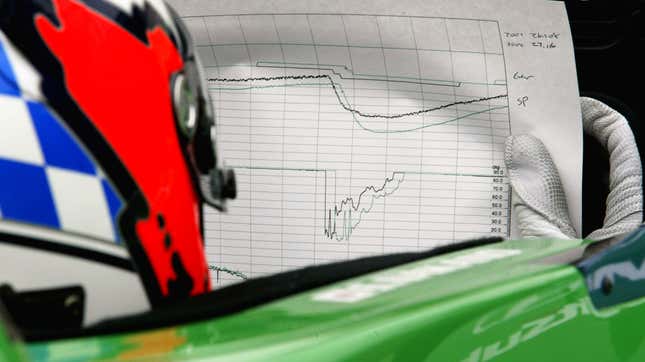

If you’ve ever seen engineers sitting on the pit wall, you can occasionally catch a glimpse of some complex graphs and charts with tons of lines and little boxes of numbers. That right there? That’s telemetry.

When you get down to it, it’s not super hard to read and interpret—you could probably stick one of those graphs on an SAT test and let the teens analyze away. If you watched that Sauber video I embedded above, you can see it for yourself: just by looking at some lines on a graph, you can kind of imagine a lap in your head. Drivers will often review telemetry themselves in order to understand where their faults are.

This is one of those things that requires a visual as well as a text description, so I’ll defer to Chain Bear, who does a great job reading some telemetry from Albert Park.

Here are some basic rules to follow:

- The graph often represents one lap around a track (that’s the x-axis)

- Sectors and turns can thus be mapped onto the graph, enabling you to tell what the car is doing very specifically throughout the lap

- Each line on the graph has its own scale, available on the y-axis

That’s all well and good, but how are you supposed to know if your lap’s telemetry is, well, normal? There are a few different ways to do it:

- Compare to your teammate

- Compare to telemetry from past years

- Compare to simulated runs of the track

- Compare to your other laps

Let’s say you want to compare your lap to your teammate’s. To make visualization easier, teams measure deltas, or the difference between one data point and another. So, when we talk about lap time deltas between Sebastian Vettel and Charles Leclerc, we’re talking about the difference in time between their laps.

The line you add to that graph will also correspond directly to areas of the track where your teammate is faster or slower. If Vettel is losing tons of time on turn four, you can see that, then look at all the other data coming in before and during turn four to see what’s going on—maybe it’s a braking problem, or maybe Vettel should change his line.

(Seriously, it’s hard to describe this in words. There are great visuals in the Chain Bear video that can help you understand so much better!)

And that’s pretty much all there is to it. As with anything, it can take practice to be able to read a telemetry chart with just one look, but once you can, you’ve just unlocked a whole world of knowledge that can be the difference between a third row start and a pole position.