The song burbles and snaps beneath the beat of a droning metronomic drum machine. A synthesizer warbles, like the underlying score to a dystopian thriller. The lyrics are spoken more than sung, in an accent that sounds vaguely European. After calling out bread and cheese, fine white wines, chic designer clothing and fashion magazines like L’oumo Vogue and GQ, we get to this verse:

Smoking on his cigarette

Listening to his car cassette

Cruising with his hot playmate

In his Porsche Nine-Two-Eight

The song is “Sharevari,” the first single from the absurdly monikered Detroit group anumberofnames. Released in 1981, it was created by Detroit high schoolers Paul Lesley and Sterling Jones. Named after an upscale New York clothing boutique, and Charivari, a social club, it is typically cited as one of the first Techno songs, a category of DJ’d electronic music that grew out of the Progressive gay/Black/Latino dance music scene of the late 1970s, after racism and homophobia conspired to make anything labeled Disco an anathema.

Another early song from the Detroit Techno pantheon, “Night Drive (Thru Babylon)” hosts a comparable beat and singing style. It was created by Juan Atkins, who formed the foundational Techno outfit Cybotron with Richard Davis when he was just 18, in 1980, and was, along with Derrick May and Kevin Saunderson, part of the core “Belleville Three” credited with helping to form the musical style. Atkins’ automotive obsession could be heard in some of his earliest tracks, like “Cosmic Cars” from 1981.

Sitting in my car, driving very far

Driving all alone, far away from home

Music’s playing loud, a hundred thirty miles

Stepping on the gas, accelerating fast

“Night Drive,” released under Atkins’ Model 500 alias, continues this obsession, citing Teutonic automotive references similar to those in “Sharevari.”

Well ... I’m driving in a black on black-on-black Porsche 924

I’m tempting fate a little bit more

My head is filled with techno beats, Metro Times, Face magazine

Shadows out of time and space

As a native Detroiter, a gay guy weaned on the Electrifying Mojo, New Wave and Frankie Knuckles, and the owner of a vintage front-engine Porsche, I have long wondered what was going on in these songs. So, as an automotive writer with a deep interest in cars and culture, I sought answers.

“Cars in Detroit have always a symbol of success and status,” says Todd Johnson, a promoter of the original Charevari Detroit social club for which the aforementioned song was named. “And while most of the scene back then came from middle-class African Americans or white kids, in Detroit, and 75 percent of them probably came from Big Three auto industry families, Europe was something to aspire to.”

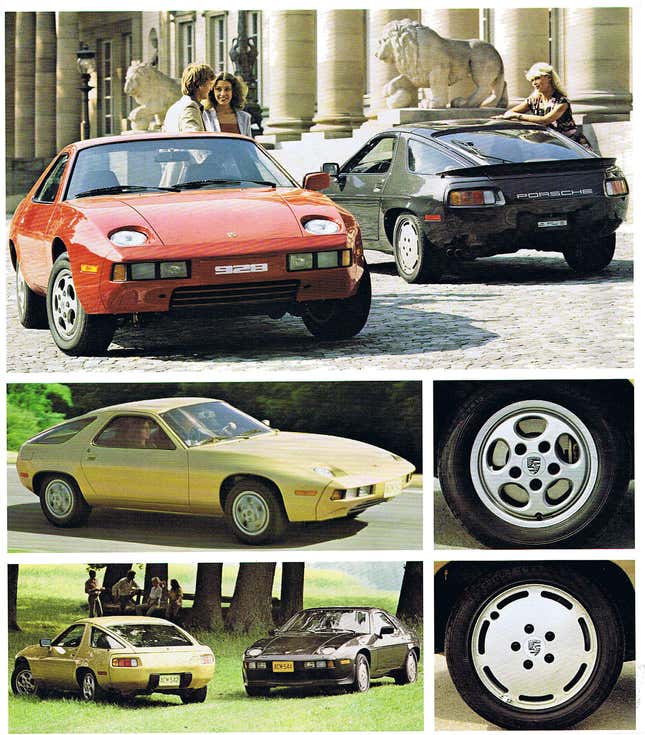

Johnson explains the allure of the Continent. “The European thing seemed cooler at the time than some Midwestern factory town like Detroit. You couldn’t have a song about a Pontiac Bonneville or a Ford Country Squire station wagon, but you could sing about a Porsche 928,” he says, laughing. “Porsche’s whole advertising back then was selling that this was something to aspire to. You become a success, you get a Porsche. It was the anti-Detroit blue collar Big Three thing.”

Other experts on the Detroit music scene from that period concur on this idea of German cars holding a particular allure to young people from the Motor City.

“The origins of Techno come from this idea of sophisticated Detroit teenagers organizing parties in which they were really into high fashion and luxury,” says Tamara Warren, a writer and native Detroiter who covered Techno for Verve, Accelerator and The Detroit Free Press. “And, being Detroiters, they could appreciate fine engineering. If you put it into the context of the time, early ’80s Detroit, what the city was like then, you have the end of the glory of the dominance of the Detroit automakers, yet many people who had a decent middle class existence, because there were still many opportunities within the auto industry. At the same time you have the juxtaposition of what the city was up against — racism and redlining — and these young people dreaming of otherworldliness but affected by all these touch-points in an industrial city.”

In addition, there was an affinity for Germany among Detroit youth, in terms of the type and quality of their industrial and creative products, especially when contrasted, as Warren and Johnson note, with the decline of American products like cars during the era in which this music was being produced.

“A lot of German products started going down not just as class symbols, but as being well made. German cars and German fashion, like Hugo Boss,” Johnson says. But, he feels that the connection goes deeper than this. “I think there’s a love affair between Detroit and Germany that had a lot to do with the type of economies — big motor city, factory towns,” he says. “I think there’s a kinship between the kind of people that developed from those working class environments.”

This affection, of course, filtered down to music. Or, perhaps, more relevantly, up from music.

“Juan Atkins has said that one of his biggest influences was Kraftwerk,” Warren says. “He was unapologetically into and fascinated by the sounds and production value of what was happening in Germany in the mid-to-late ’70s. Juan was well-read, curious, interested in all of these things, but understood the context of what Detroit was all about. He talks about factories, and labor force, and the grind of engines impacting his own sounds.”

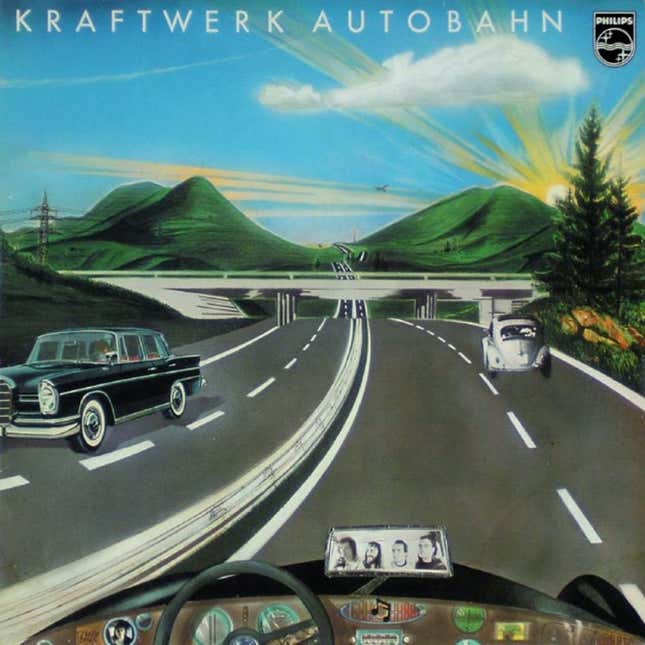

In the early ’80s, with the demise of the 911 in the plans, Porsche was staking its future on front-engine sports cars like the 928 and 924. These cars were built not just for acceleration and handling, but for high-speed comfort, for driving on the very highways that Kraftwerk was inspired by and celebrated in its groundbreaking electronic album, “Autobahn.” That album was released in 1974 and featured a vintage black fin-tail Mercedes 280 SE and a vintage white Volkswagen Beetle driving down the titular speed-limitless roadway. But had the album been pressed just a couple of years later, the sleek and futuristic shapes of the 924 or 928 would have seemed perfectly in place here.

Perhaps it was no surprise that the music created by these Techno pioneers, celebrating German “Krautrock” and German cars, was first broadly revered not in Detroit but in the nightclubs of Germany. “These young guys got their first taste of fame or success or adoration, in Germany,” Johnson says. “They weren’t embraced in the radio, in the media or walking around in Detroit. But in Berlin, they were treated like rock stars, and that’s intoxicating. So part of that love affair comes around. They could go over there and be a star.”

Musicians like Juan Atkins and Derrick May went on to jet back and forth between Europe and Detroit, establishing the role of the celebrity international DJ. When they returned home, or lived overseas, did they ever achieve their dream of purchasing and driving a Porsche?

“I don’t know personally,” Johnson says. “I know there were some fine cars bought. There were a lot of sports cars bought. I mean, if you talk to any of those guys, even today, when they had their first I made it moment, they bought a new car — before education, investment, housing. They could be living in their grandma’s basement, but they went out and bought a brand new car. The dream car.”

The influence of Germany has hardly waned.

“All over Germany, Detroit Techno is revered,” Warren says. “To this day, you can go into any record store in Germany and there’s a Detroit Techno section. There’s probably a better understanding of the history of that music there than anywhere outside of Detroit.”

Brett Berk is a New York City-based freelance writer who covers the intersection of cars and culture. His work has appeared in a broad range of publications, including Architectural Digest, Billboard, Car and Driver, GQ, The New York Times, Vogue, and Vanity Fair.